The Role of Alcohol Dehydrogenase Genes in the Development of Fetal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of a Microsomal Retinol Dehydrogenase Gene from Amphioxus: Retinoid Metabolism Before Vertebrates

Chemico-Biological Interactions 130–132 (2001) 359–370 www.elsevier.com/locate/chembiont Characterization of a microsomal retinol dehydrogenase gene from amphioxus: retinoid metabolism before vertebrates Diana Dalfo´, Cristian Can˜estro, Ricard Albalat, Roser Gonza`lez-Duarte * Departament de Gene`tica, Facultat de Biologia, Uni6ersitat de Barcelona, A6. Diagonal, 645, E-08028, Barcelona, Spain Abstract Amphioxus, a member of the subphylum Cephalochordata, is thought to be the closest living relative to vertebrates. Although these animals have a vertebrate-like response to retinoic acid, the pathway of retinoid metabolism remains unknown. Two different enzyme systems — the short chain dehydrogenase/reductases and the cytosolic medium-chain alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs) — have been postulated in vertebrates. Nevertheless, recent data show that the vertebrate-ADH1 and ADH4 retinol-active forms originated after the divergence of cephalochordates and vertebrates. Moreover, no data has been gathered in support of medium-chain retinol active forms in amphioxus. Then, if the cytosolic ADH system is absent and these animals use retinol, the microsomal retinol dehydrogenases could be involved in retinol oxidation. We have identified the genomic region and cDNA of an amphioxus Rdh gene as a preliminary step for functional characterization. Besides, phyloge- netic analysis supports the ancestral position of amphioxus Rdh in relation to the vertebrate forms. © 2001 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Retinol dehydrogenase; Retinoid metabolism; Amphioxus * Corresponding author. Fax: +34-93-4110969. E-mail address: [email protected] (R. Gonza`lez-Duarte). 0009-2797/01/$ - see front matter © 2001 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S0009-2797(00)00261-1 360 D. -

Enzyme DHRS7

Toward the identification of a function of the “orphan” enzyme DHRS7 Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Selene Araya, aus Lugano, Tessin Basel, 2018 Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Alex Odermatt (Fakultätsverantwortlicher) und Prof. Dr. Michael Arand (Korreferent) Basel, den 26.6.2018 ________________________ Dekan Prof. Dr. Martin Spiess I. List of Abbreviations 3α/βAdiol 3α/β-Androstanediol (5α-Androstane-3α/β,17β-diol) 3α/βHSD 3α/β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 17β-HSD 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase 17αOHProg 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone 20α/βOHProg 20α/β-Hydroxyprogesterone 17α,20α/βdiOHProg 20α/βdihydroxyprogesterone ADT Androgen deprivation therapy ANOVA Analysis of variance AR Androgen Receptor AKR Aldo-Keto Reductase ATCC American Type Culture Collection CAM Cell Adhesion Molecule CYP Cytochrome P450 CBR1 Carbonyl reductase 1 CRPC Castration resistant prostate cancer Ct-value Cycle threshold-value DHRS7 (B/C) Dehydrogenase/Reductase Short Chain Dehydrogenase Family Member 7 (B/C) DHEA Dehydroepiandrosterone DHP Dehydroprogesterone DHT 5α-Dihydrotestosterone DMEM Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium DMSO Dimethyl Sulfoxide DTT Dithiothreitol E1 Estrone E2 Estradiol ECM Extracellular Membrane EDTA Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid EMT Epithelial-mesenchymal transition ER Endoplasmic Reticulum ERα/β Estrogen Receptor α/β FBS Fetal Bovine Serum 3 FDR False discovery rate FGF Fibroblast growth factor HEPES 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-Piperazineethanesulfonic Acid HMDB Human Metabolome Database HPLC High Performance Liquid Chromatography HSD Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase IC50 Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration LNCaP Lymph node carcinoma of the prostate mRNA Messenger Ribonucleic Acid n.d. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

Evolution of 17Beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases and Their Role in Androgen, Estrogen and Retinoid Action

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Evolution of 17beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases and Their Role in Androgen, Estrogen and Retinoid Action Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1md640v5 Journal Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 171 Author Baker, Michael E Publication Date 2001 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Molec ular and Cellular Endocrinol ogy vol. 171, pp. 211 -215, 2001. Evolution of 17 -Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases and Their Role in Androgen, Estrogen and Retinoid Action Michael E. Baker Department of Medicine, 0823 University of California, San Diego 950 0 Gilman Drive La Jolla, CA 92093 -0823 phone: 858 -534 -8317 fax: 858 -822 -0873 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. 17 -hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (17 -HSDs) regulate androgen and estrogen concentrations in mammals. By 1995, four distinct enzymes with 17 -HSD activity had been identified: 17 -HSD -types 1 and 3, which in vivo are NADPH -dependent reductases; 17 -HSD - types 2 and 4, which in vivo are NAD +-dependent oxidases. Since then six additional enzymes with 17 -HSD activity have been isolated from mammal s. With the exception of 17 -HSD –type 5, which belongs to the aldoketo -reductase (AKR) family, these 17 -HSDs belong to the short chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR) family. Several 17 -HSDs appear to be examples of convergent evolution. That is, 17 -HSD activity arose several times from different ancestors. Some 17 -HSDs share a common ancestor with retinoid oxido -reductases and have retinol dehydrogenase activity. 17 -HSD -types 2, 6 and 9 appear to have diverged from ancestral retinoid dehydrogenas es early in the evolution of deuterostomes during the Cambrian, about 540 million years ago. -

SELENOF) with Retinol Dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11

Tian et al. Nutrition & Metabolism (2018) 15:7 DOI 10.1186/s12986-017-0235-x RESEARCH Open Access The interaction of selenoprotein F (SELENOF) with retinol dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11) implied a role of SELENOF in vitamin A metabolism Jing Tian1* , Jiapan Liu1, Jieqiong Li2, Jingxin Zheng3, Lifang Chen4, Yujuan Wang1, Qiong Liu1 and Jiazuan Ni1 Abstract Background: Selenoprotein F (SELENOF, was named as 15-kDa selenoprotein) has been reported to play important roles in oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and carcinogenesis. However, the biological function of SELENOF is still unclear. Methods: A yeast two-hybrid system was used to screen the interactive protein of SELENOF in a human fetal brain cDNA library. The interaction between SELENOF and interactive protein was validated by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and pull-down assays. The production of retinol was detected by high performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC). Results: Retinol dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11) was found to interact with SELENOF. RDH11 is an enzyme for the reduction of all-trans-retinaldehyde to all-trans-retinol (vitamin A). The production of retinol was decreased by SELENOF overexpression, resulting in more retinaldehyde. Conclusions: SELENOF interacts with RDH11 and blocks its enzyme activity to reduce all-trans-retinaldehyde. Keywords: SELENOF (Seleonoprotein F) , Yeast two hybrid system, Protein-protein interaction, Retinol dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11), Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP), Pull- down, Retinol (vitamin a), Retinaldehyde Background SELENOF shows that the protein contains a Selenium (Se) is a necessary trace element for human thioredoxin-like motif. The redox potential of this motif health. -

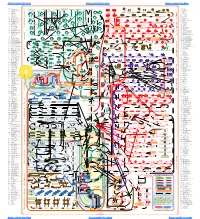

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

RDH5 Gene Retinol Dehydrogenase 5

RDH5 gene retinol dehydrogenase 5 Normal Function The RDH5 gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called 11-cis retinol dehydrogenase 5, which is necessary for normal vision, especially in low-light conditions (night vision). This enzyme is found in a thin layer of cells at the back of the eye called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This cell layer supports and nourishes the retina, which is the light-sensitive tissue in the inner lining of the back of the eye (the fundus). 11-cis retinol dehydrogenase 5 is involved in a multi-step process called the visual cycle, by which light entering the eye is converted into electrical signals that are interpreted as vision. An integral operation of the visual cycle is the recycling of a molecule called 11- cis retinal, which is a form of vitamin A that is needed for the conversion of light to electrical signals. The retinol dehydrogenase 5 enzyme converts a molecule called 11- cis retinol to 11-cis retinal. In light-sensing cells in the retina known as photoreceptors, 11-cis retinal combines with a protein called an opsin to form a photosensitive pigment. When light hits this pigment, 11-cis retinal is altered, forming another molecule called all- trans retinal. This conversion triggers a series of chemical reactions that create electrical signals. 11-cis retinol dehydrogenase 5 then helps convert all-trans retinal back to 11-cis retinal so the visual cycle can begin again. The eyes contain two types of photoreceptors, rods and cones. Rods are needed for vision in low light, while cones are needed for vision in bright light, including color vision. -

Supplemental Figures 04 12 2017

Jung et al. 1 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES 2 3 Supplemental Figure 1. Clinical relevance of natural product methyltransferases (NPMTs) in brain disorders. (A) 4 Table summarizing characteristics of 11 NPMTs using data derived from the TCGA GBM and Rembrandt datasets for 5 relative expression levels and survival. In addition, published studies of the 11 NPMTs are summarized. (B) The 1 Jung et al. 6 expression levels of 10 NPMTs in glioblastoma versus non‐tumor brain are displayed in a heatmap, ranked by 7 significance and expression levels. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. 8 2 Jung et al. 9 10 Supplemental Figure 2. Anatomical distribution of methyltransferase and metabolic signatures within 11 glioblastomas. The Ivy GAP dataset was downloaded and interrogated by histological structure for NNMT, NAMPT, 12 DNMT mRNA expression and selected gene expression signatures. The results are displayed on a heatmap. The 13 sample size of each histological region as indicated on the figure. 14 3 Jung et al. 15 16 Supplemental Figure 3. Altered expression of nicotinamide and nicotinate metabolism‐related enzymes in 17 glioblastoma. (A) Heatmap (fold change of expression) of whole 25 enzymes in the KEGG nicotinate and 18 nicotinamide metabolism gene set were analyzed in indicated glioblastoma expression datasets with Oncomine. 4 Jung et al. 19 Color bar intensity indicates percentile of fold change in glioblastoma relative to normal brain. (B) Nicotinamide and 20 nicotinate and methionine salvage pathways are displayed with the relative expression levels in glioblastoma 21 specimens in the TCGA GBM dataset indicated. 22 5 Jung et al. 23 24 Supplementary Figure 4. -

Functional and Structural Studies of AKR1B15 and AKR1B16: Two Novel Additions to Human and Mouse Aldo-Keto Reductase Superfamily

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Functional and structural studies of AKR1B15 and AKR1B16: Two novel additions to human and mouse aldo-keto reductase superfamily Mem`oriapresentada per JOAN GIMENEZ´ DEJOZ per optar al Grau de Doctor en Bioqu´ımicai Biologia Molecular Treball realitzat al departament de Bioqu´ımicai Biologia Molecular de la Universitat Aut`onomade Barcelona, sota la direcci´odels Doctors SERGIO PORTE´ ORDUNA, JAUME FARRES´ VICEN´ i XAVIER PARES´ CASASAMPERA Sergio Port´eOrduna Jaume Farr´esVic´en Xavier Par´esCasasampera Joan Gim´enezDejoz Bellaterra, 17 de juny de 2016 2 Agra¨ıments En primer lloc vull agrair als caps del grup, el Dr. Jaume Farr´esi el Dr. Xavier Par´esl'oportunitat de posar un peu a la ci`encia,iniciar-me en la carrera cient´ıfica,els seus bons consells i l’obtenci´o final d'aquesta tesi. Tamb´evoldria agrair especialment a tots els ADHs amb qui he compartit laboratori, sense vosaltres aix`ono hauria estat possible. Gr`aciesper aguantar tants dies a les fosques! Al Sergio-せんせい, per tot el que m'has ensenyat durant aquests anys, la bona guia, direcci´o, les inacabables correccions, per ensenyar-me a ser cr´ıticamb la meva pr`opiafeina i intentar sempre ser rigor´osi auto exigent tant amb els experiments com amb la redacci´oi preparaci´ode les figures (repassar cada figura mil cops buscant defectes abans de donar-la per bona ja s'ha convertit en costum) i tots i cada un dels inacabables \Podries..."que tant hem trobat a faltar en la `epoca final. -

The Role of AKR1B10 in Physiology and Pathophysiology

H OH metabolites OH Review The Role of AKR1B10 in Physiology and Pathophysiology Satoshi Endo 1,* , Toshiyuki Matsunaga 2 and Toru Nishinaka 3 1 Laboratory of Biochemistry, Gifu Pharmaceutical University, Gifu 501-1196, Japan 2 Education Center of Green Pharmaceutical Sciences, Gifu Pharmaceutical University, Gifu 502-8585, Japan; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Biochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Osaka Ohtani University, Tondabayashi 584-8540, Osaka, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: AKR1B10 is a human nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent reductase belonging to the aldo-keto reductase (AKR) 1B subfamily. It catalyzes the reduction of aldehydes, some ketones and quinones, and interacts with acetyl-CoA carboxylase and heat shock protein 90α. The enzyme is highly expressed in epithelial cells of the stomach and intestine, but down-regulated in gastrointestinal cancers and inflammatory bowel diseases. In contrast, AKR1B10 expression is low in other tissues, where the enzyme is upregulated in cancers, as well as in non- alcoholic fatty liver disease and several skin diseases. In addition, the enzyme’s expression is elevated in cancer cells resistant to clinical anti-cancer drugs. Thus, growing evidence supports AKR1B10 as a potential target for diagnosing and treating these diseases. Herein, we reviewed the literature on the roles of AKR1B10 in a healthy gastrointestinal tract, the development and progression of cancers and acquired chemoresistance, in addition to its gene regulation, functions, and inhibitors. Keywords: aldo-keto reductases; AKR1B10; biomarkers Citation: Endo, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Nishinaka, T. The Role of AKR1B10 in 1. Introduction Physiology and Pathophysiology. -

All Enzymes in BRENDA™ the Comprehensive Enzyme Information System

All enzymes in BRENDA™ The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System http://www.brenda-enzymes.org/index.php4?page=information/all_enzymes.php4 1.1.1.1 alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B1 D-arabitol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.2 alcohol dehydrogenase (NADP+) 1.1.1.B3 (S)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.3 homoserine dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B4 (R)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.4 (R,R)-butanediol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.5 acetoin dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B5 NADP-retinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.6 glycerol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.7 propanediol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.8 glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD+) 1.1.1.9 D-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.10 L-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.11 D-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.12 L-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.13 L-arabinitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.14 L-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.15 D-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.16 galactitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.17 mannitol-1-phosphate 5-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.18 inositol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.19 glucuronate reductase 1.1.1.20 glucuronolactone reductase 1.1.1.21 aldehyde reductase 1.1.1.22 UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.23 histidinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.24 quinate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.25 shikimate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.26 glyoxylate reductase 1.1.1.27 L-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.28 D-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.29 glycerate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.30 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.31 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.32 mevaldate reductase 1.1.1.33 mevaldate reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.34 hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.35 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA -

Biochemical Journal of Many Body Tissues, Such As Skin, Bone and the Vasculature, As of Both Specificities [3,4]

www.biochemj.org Biochem. J. (2011) 440, 335–344 (Printed in Great Britain) doi:10.1042/BJ20111286 335 Retinaldehyde is a substrate for human aldo–keto reductases of the 1C subfamily F. Xavier RUIZ*, Sergio PORTE*,´ Oriol GALLEGO*, Armando MORO*, Albert ARDEVOL` †‡, Alberto DEL R´IO-ESP´INOLA*, Carme ROVIRA†‡§, Jaume FARRES*´ and Xavier PARES*´ 1 *Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Universitat Autonoma` de Barcelona, E-08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain, †Laboratori de Modelitzacio´ i Simulacio´ Computacional, Parc Cient´ıfic de Barcelona, Josep Samitier 1-5, E-08028 Barcelona, Spain, ‡Institut de Qu´ımica Teorica` i Computacional (IQTCUB), Parc Cient´ıfic de Barcelona, Mart´ı i Franques` 1, 08028 Barcelona, Spain, and §Institucio´ Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats (ICREA), Passeig Llu´ıs Companys 23, E-08010 Barcelona, Spain Human AKR (aldo–keto reductase) 1C proteins (AKR1C1– the use of the inhibitor flufenamic acid, indicated a relevant AKR1C4) exhibit relevant activity with steroids, regulating role for endogenous AKR1Cs in retinaldehyde reduction in hormone signalling at the pre-receptor level. In the present study, MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Overexpression of AKR1C proteins investigate the activity of the four human AKR1C enzymes with depleted RA (retinoic acid) transactivation in HeLa cells treated retinol and retinaldehyde. All of the enzymes except AKR1C2 with retinol. Thus AKR1Cs may decrease RA levels in vivo. showed retinaldehyde reductase activity with low Km values Finally, by using lithocholic acid as an AKR1C3 inhibitor and − 1 (∼1 μM). The kcat values were also low (0.18–0.6 min ), UVI2024 as an RA receptor antagonist, we provide evidence except for AKR1C3 reduction of 9-cis-retinaldehyde whose that the pro-proliferative action of AKR1C3 in HL-60 cells − 1 kcat was remarkably higher (13 min ).