The Mycetozoa of North America, Based Upon the Specimens in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protozoologica Special Issue: Protists in Soil Processes

Acta Protozool. (2012) 51: 201–208 http://www.eko.uj.edu.pl/ap ActA doi:10.4467/16890027AP.12.016.0762 Protozoologica Special issue: Protists in Soil Processes Review paper Ecology of Soil Eumycetozoans Steven L. STEPHENSON1 and Alan FEEST2 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas, USA; 2Institute of Advanced Studies, University of Bristol and Ecosulis ltd., Newton St Loe, Bath, United Kingdom Abstract. Eumycetozoans, commonly referred to as slime moulds, are common to abundant organisms in soils. Three groups of slime moulds (myxogastrids, dictyostelids and protostelids) are recognized, and the first two of these are among the most important bacterivores in the soil microhabitat. The purpose of this paper is first to provide a brief description of all three groups and then to review what is known about their distribution and ecology in soils. Key words: Amoebae, bacterivores, dictyostelids, myxogastrids, protostelids. INTRODUCTION that they are amoebozoans and not fungi (Bapteste et al. 2002, Yoon et al. 2008, Baudalf 2008). Three groups of slime moulds (myxogastrids, dic- One of the idiosyncratic branches of the eukary- tyostelids and protostelids) are recognized (Olive 1970, otic tree of life consists of an assemblage of amoe- 1975). Members of the three groups exhibit consider- boid protists referred to as the supergroup Amoebozoa able diversity in the type of aerial spore-bearing struc- (Fiore-Donno et al. 2010). The most diverse members tures produced, which can range from exceedingly of the Amoebozoa are the eumycetozoans, common- small examples (most protostelids) with only a single ly referred to as slime moulds. Since their discovery, spore to the very largest examples (certain myxogas- slime moulds have been variously classified as plants, trids) that contain many millions of spores. -

Myxomycetes NMW 2012Orange, Updated KS 2017.Docx

Myxomycete (Slime Mould) Collection Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales (NMW) Alan Orange (2012), updated by Katherine Slade (2017) Myxomycetes (true or plasmodial slime moulds) belong to the Eumycetozoa, within the Amoebozoa, a group of eukaryotes that are basal to a clade containing animals and fungi. Thus although they have traditionally been studied by mycologists they are distant from the true fungi. Arrangement & Nomenclature Slime Mould specimens in NMW are arranged in alphabetical order of the currently accepted name (as of 2012). Names used on specimen packets that are now synonyms are cross referenced in the list below. The collection currently contains 157 Myxomycete species. Specimens are mostly from Britain, with a few from other parts of Europe or from North America. The current standard work for identification of the British species is: Ing, B. 1999. The Myxomycetes of Britain and Ireland. An Identification Handbook. Slough: Richmond Publishing Co. Ltd. Nomenclature follows the online database of Slime Mould names at www.eumycetozoa.com (accessed 2012). This database is largely in line with Ing (1999). Preservation The feeding stage is a multinucleate motile mass known as a plasmodium. The fruiting stage is a dry, fungus-like structure containing abundant spores. Mature fruiting bodies of Myxomycetes can be collected and dried, and with few exceptions (such as Ceratiomyxa) they preserve well. Plasmodia cannot be preserved, but it is useful to record the colour if possible. Semi-mature fruiting bodies may continue to mature if collected with the substrate and kept in a cool moist chamber. Collected plasmodia are unlikely to fruit. Specimens are stored in boxes to prevent crushing; labels should not be allowed to touch the specimen. -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

A Novel Structure Learning Algorithm for Bayesian Networks Inspired by Physarum Polycephalum

Physarum Learner: A Novel Structure Learning Algorithm for Bayesian Networks inspired by Physarum Polycephalum DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DES DOKTORGRADES DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (DR. RER. NAT.) DER FAKULTAT¨ FUR¨ BIOLOGIE UND VORKLINISCHE MEDIZIN DER UNIVERSITAT¨ REGENSBURG vorgelegt von Torsten Schon¨ aus Wassertrudingen¨ im Jahr 2013 Der Promotionsgesuch wurde eingereicht am: 21.05.2013 Die Arbeit wurde angeleitet von: Prof. Dr. Elmar W. Lang Unterschrift: Torsten Schon¨ ii iii Abstract Two novel algorithms for learning Bayesian network structure from data based on the true slime mold Physarum polycephalum are introduced. The first algorithm called C- PhyL calculates pairwise correlation coefficients in the dataset. Within an initially fully connected Physarum-Maze, the length of the connections is given by the inverse correla- tion coefficient between the connected nodes. Then, the shortest indirect path between each two nodes is determined using the Physarum Solver. In each iteration, a score of the surviving edges is increased. Based on that score, the highest ranked connections are combined to form a Bayesian network. The novel C-PhyL method is evaluated with different configurations and compared to the LAGD Hill Climber, Tabu Search and Simu- lated Annealing on a set of artificially generated and real benchmark networks of different characteristics, showing comparable performance regarding quality of training results and increased time efficiency for large datasets. The second novel algorithm called SO-PhyL is introduced and shown to be able to out- perform common score based structure learning algorithms for some benchmark datasets. SO-PhyL first initializes a fully connected Physarum-Maze with constant length and ran- dom conductivities. In each Physarum Solver iteration, the source and sink nodes are changed randomly and the conductivities are updated. -

A Revised Classification of Naked Lobose Amoebae (Amoebozoa

Protist, Vol. 162, 545–570, October 2011 http://www.elsevier.de/protis Published online date 28 July 2011 PROTIST NEWS A Revised Classification of Naked Lobose Amoebae (Amoebozoa: Lobosa) Introduction together constitute the amoebozoan subphy- lum Lobosa, which never have cilia or flagella, Molecular evidence and an associated reevaluation whereas Variosea (as here revised) together with of morphology have recently considerably revised Mycetozoa and Archamoebea are now grouped our views on relationships among the higher-level as the subphylum Conosa, whose constituent groups of amoebae. First of all, establishing the lineages either have cilia or flagella or have lost phylum Amoebozoa grouped all lobose amoe- them secondarily (Cavalier-Smith 1998, 2009). boid protists, whether naked or testate, aerobic Figure 1 is a schematic tree showing amoebozoan or anaerobic, with the Mycetozoa and Archamoe- relationships deduced from both morphology and bea (Cavalier-Smith 1998), and separated them DNA sequences. from both the heterolobosean amoebae (Page and The first attempt to construct a congruent molec- Blanton 1985), now belonging in the phylum Per- ular and morphological system of Amoebozoa by colozoa - Cavalier-Smith and Nikolaev (2008), and Cavalier-Smith et al. (2004) was limited by the the filose amoebae that belong in other phyla lack of molecular data for many amoeboid taxa, (notably Cercozoa: Bass et al. 2009a; Howe et al. which were therefore classified solely on morpho- 2011). logical evidence. Smirnov et al. (2005) suggested The phylum Amoebozoa consists of naked and another system for naked lobose amoebae only; testate lobose amoebae (e.g. Amoeba, Vannella, this left taxa with no molecular data incertae sedis, Hartmannella, Acanthamoeba, Arcella, Difflugia), which limited its utility. -

A Survey of Myxomycetes from the Black Hills of South Dakota and the Bear Lodge Mountains of Wyoming

Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science, Vol. 89 (2010) 45 A SURVEY OF MYXOMYCETES FROM THE BLACK HILLS OF SOUTH DAKOTA AND THE BEAR LODGE MOUNTAINS OF WYOMING A. Gabel1*, E. Ebbert2, M. Gabel1 and L. Zierer2 1Biology Department Black Hills State University 1200 University Spearfish, South Dakota 57799 2Deceased *[email protected] ABSTRACT Fruiting bodies of slime molds were collected intermittently from the field from 1990-2009. During the summers of 2007-2009 slime molds also were cultured in moist chambers from downed, decaying wood, dried deciduous leaf litter, and dried grass litter that was gathered three times each summer from four areas at each of the following six sites. Alabaugh Canyon and Boles/Redbird Canyons were dry, prairie/woodlands in Fall River and Custer Counties in the southern Black Hills. Pony Gulch and Spring Creek, in the central hills were moist, broad gulches in Pennington County, and the northern hills sites were Botany Bay and Grigg’s Gulch, narrow, moist canyons in Lawrence County. Contents of a total of 648 cultures were examined. Presence of a species in a culture was considered to be a collection and some cultures contained more than one species. Eighty-two species from both field and culture surveys were identified, and 62 are considered as new records for the Black Hills, and 61 for western South Dakota. Six hundred fifty-seven collections representing 65 spe- cies developed in culture included species from all orders of Myxomycetes. Only five species occurred at a relative abundance > 5% and 20 occurred only once. -

The Occurrence of Myxomycetes on Different Decay Stages of Trunks of Picea Abies, Pinus Sylvestris and Betula Spp. in a Small Oldgrowth Forest in Southern Finland

Karstenia 42: 13- 22, 2002 The occurrence of myxomycetes on different decay stages of trunks of Picea abies, Pinus sylvestris and Betula spp. in a small oldgrowth forest in southern Finland TARJA UKKOLA UKKOLA, T. 2002: The occurrence of myxomycetes on different decay stages of trunks of Picea abies, Pinus sylvestris and Betula spp. in a small oldgrowth forest in southern Finland. - Karstenia 42: 13- 22. Helsinki. ISSN 0453-3402. The occurrence of myxomycetes was studied on fallen trunks of Picea abies, Pinus sylvestris, and Betula spp. (B. pendula and B. pubescens) in a small oldgrowth forest in southern Finland in May 1998 - September 1999. The study site is located in Luukkaa Recreation Area, and was left in pristine state in 1966. The sample trunks were chosen to represent different stages of decomposition and checked every second or fourth > eek in all for 17 times. A total of 325 myxomycete specimens representing 44 taxa in 16 genera were observed. Four taxa, Comatricha pulchella var. fusca, Lycogala exiguum, Licea cf. pus ilia, and Physarum bethelii are new records to Finland. During the study, myxomycetes were most abundant on decomposing trunks of Betula spp. (123 specimens), especially on well-decayed trunks. The species diversity was about the same on all studied tree species: 27 taxa were recorded on P abies and P sylvestris, and 22 on Betula spp. The largest di ersity was on two pine trunks with fairly soft wood (a total of 19 taxa). The common myxomycetes, Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa and Lycogala epidendrum, represent generalists in this study, being abundant and present at nearly all decay stages of all studied tree species. -

Slime Moulds

Queen’s University Biological Station Species List: Slime Molds The current list has been compiled by Richard Aaron, a naturalist and educator from Toronto, who has been running the Fabulous Fall Fungi workshop at QUBS between 2009 and 2019. Dr. Ivy Schoepf, QUBS Research Coordinator, edited the list in 2020 to include full taxonomy and information regarding species’ status using resources from The Natural Heritage Information Centre (April 2018) and The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (February 2018); iNaturalist and GBIF. Contact Ivy to report any errors, omissions and/or new sightings. Based on the aforementioned criteria we can expect to find a total of 33 species of slime molds (kingdom: Protozoa, phylum: Mycetozoa) present at QUBS. Species are Figure 1. One of the most commonly encountered reported using their full taxonomy; common slime mold at QUBS is the Dog Vomit Slime Mold (Fuligo septica). Slime molds are unique in the way name and status, based on whether the species is that they do not have cell walls. Unlike fungi, they of global or provincial concern (see Table 1 for also phagocytose their food before they digest it. details). All species are considered QUBS Photo courtesy of Mark Conboy. residents unless otherwise stated. Table 1. Status classification reported for the amphibians of QUBS. Global status based on IUCN Red List of Threatened Species rankings. Provincial status based on Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre SRank. Global Status Provincial Status Extinct (EX) Presumed Extirpated (SX) Extinct in the -

Biodiversity of Plasmodial Slime Moulds (Myxogastria): Measurement and Interpretation

Protistology 1 (4), 161–178 (2000) Protistology August, 2000 Biodiversity of plasmodial slime moulds (Myxogastria): measurement and interpretation Yuri K. Novozhilova, Martin Schnittlerb, InnaV. Zemlianskaiac and Konstantin A. Fefelovd a V.L.Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia, b Fairmont State College, Fairmont, West Virginia, U.S.A., c Volgograd Medical Academy, Department of Pharmacology and Botany, Volgograd, Russia, d Ural State University, Department of Botany, Yekaterinburg, Russia Summary For myxomycetes the understanding of their diversity and of their ecological function remains underdeveloped. Various problems in recording myxomycetes and analysis of their diversity are discussed by the examples taken from tundra, boreal, and arid areas of Russia and Kazakhstan. Recent advances in inventory of some regions of these areas are summarised. A rapid technique of moist chamber cultures can be used to obtain quantitative estimates of myxomycete species diversity and species abundance. Substrate sampling and species isolation by the moist chamber technique are indispensable for myxomycete inventory, measurement of species richness, and species abundance. General principles for the analysis of myxomycete diversity are discussed. Key words: slime moulds, Mycetozoa, Myxomycetes, biodiversity, ecology, distribu- tion, habitats Introduction decay (Madelin, 1984). The life cycle of myxomycetes includes two trophic stages: uninucleate myxoflagellates General patterns of community structure of terrestrial or amoebae, and a multi-nucleate plasmodium (Fig. 1). macro-organisms (plants, animals, and macrofungi) are The entire plasmodium turns almost all into fruit bodies, well known. Some mathematics methods are used for their called sporocarps (sporangia, aethalia, pseudoaethalia, or studying, from which the most popular are the quantita- plasmodiocarps). -

A Preliminary Checklist of Arizona Macrofungi

A PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF ARIZONA MACROFUNGI Scott T. Bates School of Life Sciences Arizona State University PO Box 874601 Tempe, AZ 85287-4601 ABSTRACT A checklist of 1290 species of nonlichenized ascomycetaceous, basidiomycetaceous, and zygomycetaceous macrofungi is presented for the state of Arizona. The checklist was compiled from records of Arizona fungi in scientific publications or herbarium databases. Additional records were obtained from a physical search of herbarium specimens in the University of Arizona’s Robert L. Gilbertson Mycological Herbarium and of the author’s personal herbarium. This publication represents the first comprehensive checklist of macrofungi for Arizona. In all probability, the checklist is far from complete as new species await discovery and some of the species listed are in need of taxonomic revision. The data presented here serve as a baseline for future studies related to fungal biodiversity in Arizona and can contribute to state or national inventories of biota. INTRODUCTION Arizona is a state noted for the diversity of its biotic communities (Brown 1994). Boreal forests found at high altitudes, the ‘Sky Islands’ prevalent in the southern parts of the state, and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa P.& C. Lawson) forests that are widespread in Arizona, all provide rich habitats that sustain numerous species of macrofungi. Even xeric biomes, such as desertscrub and semidesert- grasslands, support a unique mycota, which include rare species such as Itajahya galericulata A. Møller (Long & Stouffer 1943b, Fig. 2c). Although checklists for some groups of fungi present in the state have been published previously (e.g., Gilbertson & Budington 1970, Gilbertson et al. 1974, Gilbertson & Bigelow 1998, Fogel & States 2002), this checklist represents the first comprehensive listing of all macrofungi in the kingdom Eumycota (Fungi) that are known from Arizona. -

What Substrate Cultures Can Reveal: Myxomycetes and Myxomycete-Like Organisms from the Sultanate of Oman

Mycosphere 6 (3): 356–384(2015) ISSN 2077 7019 www.mycosphere.org Article Mycosphere Copyright © 2015 Online Edition Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/6/3/11 What substrate cultures can reveal: Myxomycetes and myxomycete-like organisms from the Sultanate of Oman Schnittler M1, Novozhilov YK2, Shadwick JDL3, Spiegel FW3, García-Carvajal E4, König P1 1Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, Ernst Moritz Arndt University Greifswald, Soldmannstr. 15, D-17487 Greifswald, Germany 2V.L. Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov St. 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia 3University of Arkansas, Department of Biological Sciences, SCEN 601, 1 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA 4Royal Botanic Garden (CSIC), Plaza de Murillo, 2, Madrid, E-28014, Spain Schnittler M, Novozhilov YK, Shadwick JDL, Spiegel FW, García-Carvajal E, König P 2015 – What substrate cultures can reveal: Myxomycetes and myxomycete-like organisms from the Sultanate of Oman. Mycosphere 6(3), 356–384, doi 10.5943/mycosphere/6/3/11 Abstract A total of 299 substrate samples collected throughout the Sultanate of Oman were analyzed for myxomycetes and myxomycete-like organisms (MMLO) with a combined approach, preparing one moist chamber culture and one agar culture for each sample. We recovered 8 forms of Myxobacteria, 2 sorocarpic amoebae (Acrasids), 19 known and 6 unknown taxa of protostelioid amoebae (Protostelids), and 50 species of Myxomycetes. Moist chambers and agar cultures completed each other. No method alone can detect the whole diversity of myxomycetes as the most species-rich group of MMLO. A significant overlap between the two methods was observed only for Myxobacteria and some myxomycetes with small sporocarps. -

9B Taxonomy to Genus

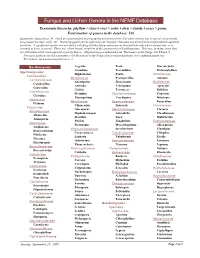

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella