Download Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CA-HPO Workshop with Edit Comments Sept20 Nm

REPORT OF MEETING CONSULTATION WORKSHOP of the REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE: HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN 2015 (MAJURO, Republic of the Marshall Islands, 21–23 October 2015) Republic of the Marshall Islands Ministry of Internal Affairs Historic Preservation Office P.O. Box 1454, Majuro, MH 96960 Phone/Fax (692) 625-4476, email: [email protected] Website: www.rmihpo.com CONSULTATION WORKSHOP of the REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE: HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN 2015 (MAJURO, Republic of the Marshall Islands, 21–23 October 2015, Sandy’s Cafe) Prepared by: Mabel Peter & Steve Titiml of the Republic of the Marshall Islands Historic Preservation Office Contents Introduction................................................................................................................... 1 Workshop Details, Agenda & Participant list.................................................................. 1 Day 1: Wednesday 21 October........................................................................................2 Opening................................................................................................................................ 2 Session 1: RMI Historic Preservation Office: Program Overview......................................... 2 Organizational Chart..................................................................................... 3 Other Activities............................................................................................. 4 Projects........................................................................................................ -

Statistical Yearbook, 2017

REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK 2017 Economic Policy, Planning and Statistics Office (EPPSO) Office of the President Republic of the Marshall Islands RMI Statistical Yearbook, 2017 Statistical Yearbook 2017 Published by: Economic Policy, Planning and Statistics Office (EPPSO), Office of the President, Republic of the Marshall Islands Publication Year: June, 2018 Technical support was provided by Inclusive Growth Thematic cluster, UNDP, Pacific Office, Suva, Fiji Disclaimer The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNDP or EPPSO. The pictures used in this publication are mostly taken from the Google search and some from the respective organization’s websites. EPPSO is not responsible if there is any violation of “copy right” issue related with any of them. 1 RMI Statistical Yearbook, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... 5 FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. 6 LIST OF ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................... 7 SUGGESTED NOTES PRIOR TO READING THIS PUBLICATION .......................................................... 10 BRIEF HISTORY OF REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS ............................................................. 12 REPUBLIC -

Flood Death Toll Is Rising

, .,/ ./ K_~.J ALE I ~___ ,H~-t\--H-a-U~R G '-~S S VOLUME 14 KWAJAlEIN ATOll, MARSHAll ISLANDS, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 1977 NUMBER 216 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * SUN & SURF * U.S. REFUGEES RETURN TO THEIR HOMES * * * AS OF 0001 HOURS 8 NOV. '77 * * RAINFAll: .03 lnch * * MONTHLY TOTAL: 2.12 inches * FLOOD DEATH TOLL IS RISING * YEARLY TOTAL' 72.82 inches * ATLANTA (UPI) -- Hundreds of flood refugees plodded back to crushed or mud-scarred homes ln * TOMORROW * the southern Appalachian and Blue Ridge Mountains and searchers pokeo through debrls for more * Hi Tlde: 0312 5.2' 1533 6.0' * vlctlms of the deadly mountaln rains. * lo Tide' 0915 0.4' 2149 0.3' * The death toll from the weekend rampage by mountain streams cllmbed to 49. Resuce workers * MOONRISE: 0517 MOONSET: 1730 * search1ng a flood-ravaged Slble college campus at Toccoa, Georgla, found the body of Dr. Jerry * SUNRISE: 0639 SUNSET 1827 * Sproull, a professor at Toccoa Falls College. Sproull was the 38th victlm of the Toccoa floodlng. *.* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Authorltles are contlnuing the search for another man st1ll mlssing and presumed dead. Governor George Busbee informed the White House he would seek federal disaster aid. * FINANCIAL NEWS * * * Searchers ln the Blue Ridge Mountalns of North Carolina found flve more bodles, boostlng the * DO~JONES INDUSTRIAL AVERAGES * state's weekend death toll to * 30 Indus. off 0.17 at 816.27 * 10. * 20 Trans. up 0.44 at 206.52 * HIGH LEVELS Of AID TO ISRAEL The bodles of two three * 15 Utils. up 0.33 at 108.71 * year-old brothers were found * 65 Stocks up 0.28 at 279.45 * yesterday a short distance * Volume: 19,210,000 Shares * AND EGYPT MA Y IMPEDE PEACE from where the1r mother's * Closing Gold Pnce $165.15 * WASHINGTON (UPI) -- Lavish ald promises to Israel and Egypt body was recovered Sunday. -

The President's Pearls

Teacher’s family Theflies Marshall Islandsin Journal for — Friday, memorial December 10, 2010 1 Six members of James de Brueys family More stories and photos, QL]LQJDPHPRULDOVHUYLFHWKDWLVH[SHFWHG SURMHFWDQGÀQLVKLWµVDLG:RUOG7HDFK·V DUHH[SHFWHGWRÁ\WR0DMXURQH[WZHHN see pages 2, 11, and 16. WRKDSSHQRQ7KXUVGD\'HFHPEHU$ $QJHOD6DXQGHUV,ISHRSOHZDQWWRVXSSRUW for a memorial service for the WorldTeach PHPRULDOVHUYLFHIRUKLPZDVKHOGWKLV LWWKH\FDQPDNHGRQDWLRQVIRULWWKURXJK WHDFKHUZKRLVEHOLHYHGWRKDYHGURZQHG WKUHHRIKLVEURWKHUVDQGVLVWHUVDQGKLV ZHHNLQ/RXLVLDQDZKHUHKLVIDPLO\OLYHV WKH:RUOG7HDFKRIÀFHLQ0DMXUR ZKHQWKHVPDOOERDWKHZDVLQZLWKWKUHH VLVWHULQODZDUHVFKHGXOHGWRYLVLWQH[W :KLOHDW%LNDUHM,VODQGGH%UXH\VKDG 2QO\RQHERG\ZDVIRXQGDQGWKRXJKD 0DUVKDOOHVHFDSVL]HGWZRZHHNVDJR 7KXUVGD\IRUWZRGD\V VWDUWHGZRUNLQJRQSODQVWREXLOGDEDV- VHFRQGERG\ZDVVLJKWHGE\D&RDVW*XDUG -DPHV·SDUHQWV·0DU\DQG-LPGH%UXH\V 7KH:RUOG7HDFKRIÀFHLQ0DMXURLVRUJD- NHWEDOOFRXUW´:HZDQWWRFRQWLQXHKLV SODQHLWZDVQRWUHFRYHUHG $1 on Winmar: The Marshall Islands Majuro ‘Jaluit all the way’ ISSN: 0892 2096 Page 15 Friday, December 10, 2010 • Volume 41, Number 50 Photos: Giff Ken Johnson quits CMIGIFF JOHNSON President Jurelang .HQQHWK:RRGEXU\-U SLF- Zedkaia made the WXUHG UHVLJQHGDV3UHVLGHQW Rongelap and Namdrik RIWKH&ROOHJHRIWKH0DUVKDOO local government pearl ,VODQGV:HGQHVGD\IRUKHDOWK sellers happy at the Tide UHDVRQVDQGWKHERDUGZDVH[- Table Saturday with SHFWHGWRPHHWZLWKKLP7KXUV- several purchases. Sales GD\WRUHYLHZDSRVVLEOHFRQWUDFW Friday and Saturday IRUFRQVXOWLQJVHUYLFHVZKHQKH netted $31,000. UHWXUQVWRWKH86 See -

Castle Bravo

Defense Threat Reduction Agency Defense Threat Reduction Information Analysis Center 1680 Texas Street SE Kirtland AFB, NM 87117-5669 DTRIAC SR-12-001 CASTLE BRAVO: FIFTY YEARS OF LEGEND AND LORE A Guide to Off-Site Radiation Exposures January 2013 Distribution A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Trade Names Statement: The use of trade names in this document does not constitute an official endorsement or approval of the use of such commercial hardware or software. This document may not be cited for purposes of advertisement. REPORT Authored by: Thomas Kunkle Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico and Byron Ristvet Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Albuquerque, New Mexico SPECIAL Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. -

I~S~Id 5Y September 1, 1952

I~s~id5y vT&- P.,L?~C07. ,T , SCI3JCX E3ii33 ~ictiond-. +oecc.rch Councii iKcisliingtor, D. C. September 1, 1952 TFBLE OF CONTRiTS Profwe ........................................................ iii ;~C!QIOV~C.dgeine~.tr; ..............+................................ iii Introduc:tioil: Lmd Teriure ................................. .. .. 1 Piiysiczl Description ........................................... 2 Lad Use ....................................................... 3 fiieciiimk? of Divisioll of Copm Shme ........................... 4 Deviations fzom thz Getlord Pc-tterr. ............................ 4 Inheritmcc 2,-ttern ..........................................mo 5 P?.trilined Usufruct ilights .................................... 6 Adoptive Rights ..........................................o.... 7 Usufruct ?.ights kcquiced ky l~ilinri'iage .......................... 8 I.!ills .......................................................... 8 Xen'mls ........................................................ 9 bhclavos ....................................................... 9 Reef 3iights .................................................... 11 Fishing Rights ................................................ 12 Game Rzserve:; .................................................. 12 Indigenous Attihdzs Tomrd Lad .............................. 13 Conce?ts of L2nd h'wrhlp ...................................... 13 Cntegoriss 3f Lmd ... 15 Bwij in A3e - fmoimje - D'ficied Lsrd ........................... 16 Conclusion ...........................................o........ -

05-01-10 Hourglass.Indd

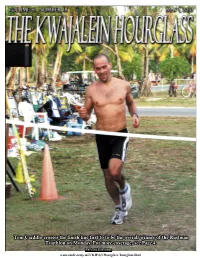

TTomom CCardilloardillo ccrossesrosses tthehe ffinishinish llineine ffirstirst ttoo ttoo bbee tthehe ooverallverall wwinnerinner ooff tthehe RRustmanustman TTriathlonriathlon oonn MMonday.onday. FForor mmoreore ccoverage,overage, sseeee PPageage 44.. y, y , PPhotohoto bbyy DDanan AAdlerdler www.smdc.army.mil/KWAJ/Hourglass/hourglass.html Letters to the editor Yokwe Yuk Women’s Club delivers $30,000 in education grants to Ebeye schools Monday Monday was a great day for the over and over again by the principals to in the Marshalls and Micronesia will go schools on Ebeye. Thanks to your hard please convey their thanks. in the mail this week. A special thank work, ladies, we were able to deliver The funds were for everything from you to each one of you who pulls a shift about $30,000 in checks in educational a water catchment system so that regularly at the Bargain Bazaar or the grants to principals on Ebeye. A grant students don’t have to leave campus to Mic Shop. You are the ones who made of $4,000 might represent a third of a get a drink of water to copy machines those checks possible. The time that school’s annual budget on Ebeye so the since the schools could never afford you volunteer is making a difference. funds are very signifi cant and make a textbooks for all of their students. We Sincerely, huge difference to the schools. gave money for much needed con- It was such a privilege for the four of struction of new classrooms at three — Jenny Norwood us who represented the YYWC in hand- schools. -

Negotiating the Borders of Empire: an Ethnography of Access On

NEGOTIATING THE BORDERS OF EMPIRE: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF ACCESS ON KWAJALEIN ATOLL, MARSHALL ISLANDS by SANDRA CRISMON (Under the Direction of J. Peter Brosius) ABSTRACT Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands, is the site of a U.S. Army missile testing base, where colonial relationships between Americans and Marshallese were examined through the analysis of physical, regulatory, cultural and discursive borders on the atoll. Ethnographic attention was focused on both local Marshallese and on American contract workers in this border situation. Findings include significant ambivalence and tensions among Americans, especially between military and civilian actors, regarding the U.S. colonial project on Kwajalein. In addition to Marshallese resistance to the military order, some American residents also resist the physical and regulatory borders that structure their everyday lives. It also becomes evident that discursive constructions of borders and relationships on the atoll have served to obscure other inequalities, and simplify a complex atoll history. Borders emerge as key sites at which to examine the tensions and power dynamics of colonial relationships. INDEX WORDS: borders/border theory, U.S. colonialism/militarism, studying up NEGOTIATING THE BORDERS OF EMPIRE: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF ACCESS ON KWAJALEIN ATOLL, MARSHALL ISLANDS by SANDRA CRISMON B.A., University of Iowa, 1991 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 -

Establishing Baseline Data to Support Sustainable Maritime Transport Services

Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility Establishing Baseline Data to Support Sustainable Maritime Transport Services Focused on the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) FINAL REPORT September 2018 Establishing Baseline Data to Support Sustainable Maritime Transport Services Final Report The Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility (PRIF) is a multi-development partner coordination, research and technical assistance facility which supports infrastructure development in the Pacific. PRIF Members include: Asian Development Bank (ADB), Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), European Investment Bank (EIB), European Union (EU), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (NZMFAT), United States Department of State and the World Bank Group. This report is published by PRIF. The views expressed are those of the author and contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of ADB, its Board of Governors, the governments they represent or any of the PRIF member agencies. Furthermore, the above parties neither guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication, nor do they accept responsibility for any consequence of their application. The use of information contained in this report is encouraged, with appropriate acknowledgement. The report may only be reproduced with the permission of the PRIF Coordination Office on behalf of the PRIF members. For further information, please contact: PRIF Coordination Office c/- Asian Development Bank Level 20, 45 Clarence Street Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 2000 Tel: +61 2 8270 9444 Email: [email protected] Website: www.theprif.org Note: This project to establish the baseline data to support sustainable maritime transport services has been carried out in collaboration with GIZ, and in particular, with Mr Raffael Held, Marine Engineer Intern on the German Government funded project, Transitioning to Low Carbon Sea Transport in the Marshall Islands, managed by GIZ. -

Understanding Oceania: Celebrating the University of the South Pacific

UNDERSTANDING OCEANIA CELEBRATING THE UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC AND ITS COLLABORATION WITH THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY UNDERSTANDING OCEANIA CELEBRATING THE UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC AND ITS COLLABORATION WITH THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EDITED BY STEWART FIRTH AND VIJAY NAIDU PACIFIC SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760462888 ISBN (online): 9781760462895 WorldCat (print): 1101142803 WorldCat (online): 1101180975 DOI: 10.22459/UO.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Acronyms . ix Contributors . xiii 1 . Themes . 1 Stewart Firth 2 . A Commentary on the 50-Year History of the University of the South Pacific . 11 Vijay Naidu 3 . The Road from Laucala Bay . 35 Brij V . Lal Part 1: Balancing Tradition and Modernity 4 . Change in Land Use and Villages—Fiji: 1958–1983 . 59 R . Gerard Ward 5 . Matai Titles and Modern Corruption in Samoa: Costs, Expectations and Consequences for Families and Society . 77 Morgan Tuimalealiʻifano 6 . Making Room for Magic in Intellectual Property Policy . 91 Miranda Forsyth Part 2: Politics and Political Economy 7 . Postcolonial Political Institutions in the South Pacific Islands: A Survey . 127 Jon Fraenkel 8 . Neo-Liberalism and the Disciplining of Pacific Island States —the Dual Challenges of a Global Economic Creed and a Changed Geopolitical Order . -

MIMRA Annual Report FY2017 MIMRA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 1 Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority

Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority MIMRAMIMRA Annual Report FY2017 MIMRA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 1 Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority, PO Box 860, Majuro, Marshall Islands 96960 Phone: (692) 625-8262/825-5632 • Fax: (692) 625-5447 • www.mimra.com 2 MIMRA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 MIMRA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acting locally benefits the Marshalls internationally anagement and sustainable and the Western and Central Pacific Fish- development of our ocean re- Message from Dennis eries Commission. M sources took a big step forward Momotaro, Chairman At the international level, our National in 2017 with the holding of the First Na- of the MIMRA Board of Oceans Policy is part of a call by Pacific tional Oceans Symposium. This event Directors and Minister of Island nations for global action on our brought together national government Natural Resources and oceans with particular focus on eradicat- leaders and officials, mayors and other ing illegal, unreported and unregulated Message from MIMRA Board Chairman local government representatives, stu- Commerce. (IUU) fishing that undermines sustain- dents, non-government organization rep- able management of these resources. It Minister Dennis Momotaro resentatives, and members of the public. supports implementation of many of the Page 5 The National Oceans Symposium out- 17 Sustainable Development Goals en- comes represent wide stakeholder input dorsed by world leaders as part of Agen- into national oceans governance issues da 2030: SGG 14 “Life Below Water,” Message from MIMRA Director and commitments to addressing these is- SDG 16 “Climate Action,” SDG 2 “Zero Glen Joseph sues. -

Republic of the Marshall Islands Majuro and Kwajalein Atoll Household Water Survey Report

Republic of the Marshall Islands Majuro and Kwajalein Atoll Household Water Survey Report February 2010 Part of the EU/SOPAC Envelope B Water Mitigation Project, with additional financial and technical assistance provided by the World Bank/OECD, Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) Economic Policy, Planning and Statistics Office Office of the President P.O. Box 7 Majuro, MH 96960 Ph: (692) 625 – 3802 Fax: (692) 625 – 3805 E Mail: [email protected] Majuro and Kwajalein Atoll Water Survey Report 1 Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgements………………………………………………....pg 3 2. Water and the Millennium Development Goals………………..…pg 4 3. Key Results and Findings……………………………………….….pg 6 4. Introduction and Background………………………………….….pg 10 5. Majuro and Ebeye Household Water Survey…………………….pg 15 6. Creation of House Listings and Updating of Housing Maps…….pg 18 7. Household Description……………………………………………...pg 19 8. Population Description……………………………………………...pg 34 9. Income Description……………………………………………….....pg 40 10. Conclusions and Recommendations………………………………pg 44 11. Appendix……………………………………………………………pg 48 EPPSO and Water Project Staff Listing……………………………………….pg 48 Water Survey Form……………………………………………………………...pg 49 Examples of Majuro and Ebeye GIS – House listing Maps……………….…..pg 53 Outer Island Water Catchment Program……………………………………...pg 55 Determining the Importance of Water………………………………………....pg 56 Example of Water Management Plan………………………………………......pg 59 Overview of National IWRM Plans…………………………...………………...pg 61 Map of RMI and Majuro Atoll ……………………………..…………………..pg 64 Majuro and Kwajalein Atoll Water Survey Report 2 Acknowledgements This project was long in coming to fruition and there are many people and organizations who made the contributions necessary which contributed to the production of this report.