The International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science, and Technology for Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide:Lessom from the Rwanda Experience

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience March 1996 Published by: Steering Committee of the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda Editor: David Millwood Cover illustrations: Kiure F. Msangi Graphic design: Designgrafik, Copenhagen Prepress: Dansk Klich‚, Copenhagen Printing: Strandberg Grafisk, Odense ISBN: 87-7265-335-3 (Synthesis Report) ISBN: 87-7265-331-0 (1. Historical Perspective: Some Explanatory Factors) ISBN: 87-7265-332-9 (2. Early Warning and Conflict Management) ISBN: 87-7265-333-7 (3. Humanitarian Aid and Effects) ISBN: 87-7265-334-5 (4. Rebuilding Post-War Rwanda) This publication may be reproduced for free distribution and may be quoted provided the source - Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda - is mentioned. The report is printed on G-print Matt, a wood-free, medium-coated paper. G-print is manufactured without the use of chlorine and marked with the Nordic Swan, licence-no. 304 022. 2 The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience Study 2 Early Warning and Conflict Management by Howard Adelman York University Toronto, Canada Astri Suhrke Chr. Michelsen Institute Bergen, Norway with contributions by Bruce Jones London School of Economics, U.K. Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda 3 Contents Preface 5 Executive Summary 8 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 12 Chapter 1: The Festering Refugee Problem 17 Chapter 2: Civil War, Civil Violence and International Response 20 (1 October 1990 - 4 August -

Centers.Pdf (660.5Kb)

About the CGIAR-Supported Future Harvest Centers Founded: 1993 Turkey; Montevideo, Uruguay; Harare, Joined the CGIAR: 1993 Zimbabwe. Regional Offices: Belem-Para, Brazil; Focus: CIMMYT is an international, non- Harare, Zimbabwe; Yaounde, Cameroon; profit, agricultural research and training CIAT—Centro Internacional de Costa Rica. center dedicated to helping the poor in Agricultura Tropical Focus: CIFOR was established in 1993 as low-income countries. CIMMYT helps allevi- (International Center for Tropical part of the Consultative Group on Interna- ate poverty by increasing the profitability, Agriculture) tional Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in productivity, and sustainability of maize www.cgiar.org/ciat response to global concerns about the and wheat farming systems. Work concen- Headquarters: Cali, Colombia social, environmental, and economic conse- trates on maize and wheat, two crops Director General: Joachim Voss quences of forest loss and degradation. vitally important to food security. These Board Chair: Lauritz B. Holm-Nielsen CIFOR research produces knowledge and crops provide about one-fourth of the total Founded: 1967 methods needed to improve the well-being food calories consumed in low-income Joined the CGIAR: 1971 of forest-dependent people, and to help countries, are critical staples for poor peo- Regional Offices: Quito, Ecuador; Awassa, tropical countries manage their forests ple, and are an important source of income Ethiopia; Tegucigalpa, Honduras; Nairobi, wisely for sustained benefits. This research for poor farmers. Kenya; Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic takes place in more than two dozen coun- Republic; Lilongwe, Malawi; Managua, tries, in collaboration with numerous part- Nicaragua; Pucallpa, Peru; Arusha, Tanza- ners. Since its founding, CIFOR has also nia; Bangkok, Thailand; Kampala, played a central role in influencing global Uganda. -

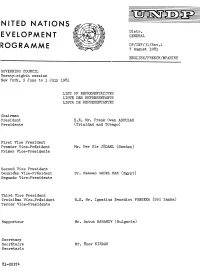

Dp/1982/Inf.7

NITED NATIONS Distr. EVELOPMENT GENERAL DP/1982/ZN?/7 ROGRAMME 27 Nay 1982 ENGLISH~FRENCH~SPANISH GOVERNING COUNCIL Special Meeting and Twenty-ninth session Geneva, 24 May to 21 June 1982 9ROVISIONAL LIST OF REPRESENTATIVES LISTE PROVISOIRE DES REDRESENTANTS LISTA PROVISORIA DE REgRESENTANTES Chairman President Mr. Douglas LINDORES (Canada) Presidente First Vice President Premier Vice-Pr~sidente H.E. Mr. Mohamed MEMMI (Tunisia) Primer Vice-Presidente Second Vice President Deuxi~me Vice-Pr~sident Mr. B.M. OZA (India) Segundo Vice-gresidente Third Vice President Troisi~me Vice-Pr4sident Mr. Anton BARAMOV (Bulgaria) Tercer Vice-Preisdente . Fourth Vice President Ouatri~me Vice-Pr4sident H.E. Dr. Miguel A. ALBORNOZ (Ecuador) Quatro Vice-Presidente Secretary Secr4taire Mr. Uner KIRDAR Secretario Corrections should be submitted in writing to the Secretariat of the Governing Council, Room E-I052, extension 4348. Les corrections doivent 6tre soumises par ~crit au Secr4tariat du Conseil d’Administration, Bureau E-1052, poste 4843. Toda correcci6~ que sea necesaria hacer sobre esta lista debe ser presentada oor escrito a la Secretarfa del Consejo de Administraci6n, Oficina E-IO52, extensi6n 4348. ir "~ ir-,~ DP/1982/INF/7 Page 1 ARGENTINA Representante: S.E. Sr. Gabriel O. MARTINEZ, Embajador, Representante Permanente ante la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas en Ginebra Representante Alterno; St. Jorge BONNASERRE, Subsecretario de Planificaci6n y Programaci6n St. Alberto L. DAVEREDE, Consejero, Misi6n Permanente en Ginebra Sr. Jorge PEREIRA, Secretario de Embajada, Misi6n Permanente en Ginebra St. Juan J. ARCURI, Secretario de Embajada, Misi6n Permanente en Ginebra Sr. Juan SOLA, Secretario de Embajada, Misi6n Permanente en Ginebra AUSTRIA Representative: Mr. -

Lucie Edwards As a Member of the Board of Trustees

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 11 August, 2016 Contact: Saurabh Upadhyay: [email protected]; Wu Junqi: [email protected]; INBAR announces the joining of Lucie Edwards as a Member of the Board of Trustees Beijing, China: On Tuesday the 2nd of August, 2016 Lucie Edwards formally joined the Board of Trustees of the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan or INBAR. Presently Lucie Edwards is a fellow at the Balsillie School of International Affairs in Waterloo, Ontario and teaches International Relations and Public Policy at the University of Waterloo and Wilfrid Laurier Universities in Waterloo, Ontario. As a doctoral candidate in Global Governance, she specializes in science and environmental policy, at the Balsillie School of International Affairs. In the past she served as an Ashley Fellow in the development studies program at Trent University, where she serves on the University’s Board of Governors. Following an illustrious career spanning 34 years with the Canadian Foreign Service she moved on to join academics. Over the three decades of her foreign service she served as the Canadian High Commissioner to Kenya, South Africa and India while also serving as an Ambassador to the UN Environment Program. Earlier, Mrs. Edwards had served as the Director General for Global Issues and Assistant Deputy Minister for Corporate Services in the Department of Foreign Affairs in Ottawa. She concluded her outstanding foreign affairs services as a Chief Strategist, integrating policy and operations. She was awarded in 1995 with a Public Service Award of Excellence for her humanitarian work during the genocide in Rwanda. She also received a merit award for her human rights work combatting Apartheid at the Canadian Embassy in Pretoria, from 1986 to 1989. -

Dp-Wgoc-V-Crp4

NITED NATIONS~~~ ~~ Distr. E V E L O P ME N T GENERAL DP/INF/BI/Rev.I ROGRAMME ~~~ 7 August 1981 ENGLISH/FRENCH/~PANISH GOVERNING COUNCIL Twenty-eighth session New York, 9 June to i July 1981 LIST OF REPRESENTATIVES LISTE DES REPRESENTANTS LISTA DE REPRESENTANTES Chairman President H.E. Mr. Frank Owen ABDULAH Presidente (Trinidad and Tobago) First Vice President Premier Vice-Pr@sident Mr. Per 01e JODAHL (Sweden) Primer Vice-Presidente Second Vice President Deuxie~e Vice-Pr@sident Dr. Hassan GADEL HAK (Egypt) Segundo Vice-Presidente Third Vice President Trolsmeme¯ °. V1ce-Pres~dent° J ° H.E. Mr. Ignatius Benedict FONSEKA (Sri Lanka) Tercer Vice-Presidente Rapporteur Mr. Anton BARAMOV (Bulgaria) Secretary Secr@taire Mr. Oner KIRDAR Secretario 81-2037h DP/INF/31/Rev. i Page 2 ARGENTINA Representantes: S.E. Sr. Juan Manuel FIGUERERO-ANT~QUEDA, Subsecretario de Relaciones Econ6micas Internacionales S.E. Dr. Juan Carlos M. BELTRAMINO, Embajador Extraordinario y Plenipotenciario, Representante Permanente ante las Naciones Unidas Representantes Alternos: Lic. Jorge BONNESSERRE, Director General de Cooperaci6n T~cnica Internacional de la Secretarfa de Planeamiento St. Jorge Hugo HERRERA VEGAS, Ministro Plenipotenciario, Misi6n Permanente Asesores: Sr. Julio C~sar FREYRE, Segundo Secretario, Misi6n Permanente St. Hugo GONZALEZ, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto AUSTRIA Representative: Mr. Erich SCHMID, Deputy Director General for Economic Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Alternate Representatives: Miss Doris MUCK, Counsellor, Permanent Mission Mr. Dietmar Hans $CHWEISGUT, Second Secretary, Permanent Mission BANGLADESH Representative: Mr. A.M.A. MUHITH, Secretary, External Resources Division, Government of Bangladesh Alternate Representatives: Mr. Lutful-la-hil MAJID, Joint Secretary, ExternaIResources Division Government of Bangladesh Mr. -

Unamir Minuar

UN ARCHIVES SERIES S K1QL BOX ry FILE -L- ACC. 1j1~/o26L I UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES .A.SSI.SYAJlCE HlSSIOII FOR RWANDA MEMORANDUM INTERIEUR To: Chief Protocol Officer Info: MA/FC From: AMA/FC Date: 8 November 1994 c Subject: REQUEST FOR VJP QUARTERS AT BBC I I am writing in my capacity as the FOTce Commander's (FC) Visits Officer.. and I am requesting that you reserve suites in the BBC fOT visiting senior officers from two separate delegations. 2. Lieutenant Colond (LCol) Andersson.. the UNHQ NY PK Desk Officer for Rwanda win be visiting die G3 Operations and Plans Staff during the period 20-26 November. I am requesting. on behalf of Leol Brimlow (G3 Plans) that LCol Andersson he granted one of the room for the period of his stay. 3. During the period 23-25 November, the Canadian Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) and some (number to be determined) of his most senior staff win be visiting with the Canadian Contingent and the Fe. He has extended the invitation to have the CDS to stay in his bouse and I am requesting that the remainder of the visiting staff be booked into the e VIP accommodation in the BBC. 4. If 3 conflict arises between the two overlapping visits.. I am sure that Leot Brimlow and I can sort it out. Should you agree to my request, I would appreciate receiving the requested keys from you on the morning of the respective arrivals. 5. For your 3l."1iOO. ~ P.T. Campbell Major Visits Officer \ . UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Office of the DFCfCOSICMO UNAMIR Force HQ Kigali Rwanda f1r c 1000.7(DFC)/G/5 og November 1994 LT COL AUSTDAL REDUCTION IN MSA I. -

Canadian Churches Against Apartheid

In Good Faith: Canadian Churches Against Apartheid http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.canp1b10040 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org In Good Faith: Canadian Churches Against Apartheid Author/Creator Pratt, Renate Contributor Tutu, Archbishop Desmond M. (preface), Hutchinson, Roger (foreword) Publisher Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion Date 1997 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Canada, South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1975-1990 Source ES Reddy Rights By kind permission of Renate Pratt and Wilfred Laurier University Press. Description Part one, 1975-80: Prelude to action - 1. -

Of 9 PSCI 282: FOREIGN POLICY WINTER

PSCI 282: FOREIGN POLICY WINTER ,2014 Lecture: Wednesdays 12:30 PM -2:30 PM Room 2038 MC. Tutorials: Section 101 Fridays 9:30-10:20 Room 345 HH Section 102 Fridays 9:30-10:20 Room 119 HH Section 103 Fridays 10:30-11:20 Room 259 HH Section 104 Fridays 10:30-11:20 Room 1106 HH Instructor: Lucie Edwards Email Address: [email protected] Office Location: Hagey Hall 351 Office Hours: F 11:30 to 1:30, or at other times by appointment. Teaching Assistants: Grad Student Sakhi Naimpoor Grad Student Chelsea Winn [email protected] [email protected] Office Hrs: F 11:30 to 1:30or by appointment Office Hrs: F 11:30-1:30 or by appointment Course Description: The course will provide an introduction to issues of international security and political economy and to identify the linkages between poverty, international politics and security. The key principles of international affairs will be explored through the use of case studies, examining key milestones in international affairs since the Second World War, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, the fall of the Berlin Wall, Tien an Men Square, and the Arab Spring. The course will be taught through a combination of lecture/discussions and small group tutorials. Course Objectives: By the end of this course, students should: Have a sufficient base of knowledge of the fundamental principles of international affairs to proceed confidently to more advanced work as scholars, engaged in reading and research in this field. Page 1 of 9 Have had the opportunity to explore international affairs from the perspective of practitioners, as a professional field which may be open to them as policymakers, as advocates and in the private sector. -

Inquiry & Insight

INQUIRY & I NSIGHT UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO ’S GRADUATE JOURNAL OF POLITICAL SCIENCE VOLUME 4, N UMBER 1 © U NIVERSITY OF WATERLOO 2011 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR In a Day of Affirmation speech delivered at the University of Cape Town, Robert F. Kennedy made reference to a Chinese curse that is as relevant today as it was on that fateful day in 1966 – “May you live in interesting times.” Recent economic crises, international political turmoil, regional conflicts and environmental concerns have certainly brought this equivocal proposition to fruition. Whether as political scientists we consider this to be a positive or a negative, it has nonetheless allowed for interesting debate and analysis of current affairs. By extension, the articles included in this year’s edition of Inquiry & Insight reflect this tumultuous environment, and explore financial issues such as the minimum wage in Canada and the European sovereign debt crisis. Furthermore, this volume includes an analysis of China’s foreign policy, human rights norms, and environmental politics – an increasingly relevant and influential field. Perhaps most reflective of these interesting times is an analysis of the 2011 Egyptian Uprising, informed by the first-hand experiences of the author in this revolutionary milieu. The fourth volume of Inquiry & Insight includes works by both Master’s and Ph.D. students from prominent universities around the world. With a record number of submissions received from a broader range of international institutions, this year’s publication furthers the success of previous issues, and strives to perpetually improve the quality of work included. To this end, particular emphasis was placed on the originality of research, as well as conceptualization, operalization and methodology. -

African Climate Scientists' Perspectives on Climate Change

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 7 — MaY 2013 Global Problems, African Solutions: African Climate Scientists’ Perspectives on Climate Change Lucie Edwards 2 CIGI • AFRICA INITIATIVE Copyright © 2013 by Lucie Edwards. DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES The CIGI-Africa Initiative Discussion Paper Series presents policy-relevant, peer-reviewed, field-based research that addresses substantive issues in the areas of conflict resolution, energy, food security, health, migration and climate change. The aim of the series is to promote discussion and advance knowledge on issues relevant to policy makers and opinion leaders in Africa. Papers in this series are written by experienced African or Canadian Published by the Africa Initiative and The Centre for researchers, and have gone through the grant review process. In select cases, papers are International Governance Innovation. commissioned studies supported by the Africa Initiative research program. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Centre for International Governance Innovation or ABOUT THE AFRICA INITIATIVE its Operating Board of Directors or International Board of Governors. The Africa Initiative is a multi-year, donor-supported program, with three components: a research program, an exchange program and an online knowledge hub, the Africa Portal. A joint undertaking by CIGI, in cooperation with the South African Institute of International Affairs, the Africa Initiative aims to contribute to the deepening of Africa’s capacity and knowledge in five thematic areas: conflict resolution, energy, food security, health and This work was carried out with the support of The migration — with special attention paid to the crosscutting theme of climate change. -

Dr. James Orbinski ’80 One of Trent’S Most Celebrated Alumni Discusses Global Citizenship “I Never Thought My Alumni Group Rates Could Save Me So Much.”

10 Scott Cannata Homecoming 12 Social Justice – Alumni Profiles 24 Remembering Freddy Hagar Winter 2012 43.1 Dr. James Orbinski ’80 One of Trent’s most celebrated alumni discusses global citizenship “I never thought my alumni group rates could save me so much.” – Kitty Huang Satisfied client since 2009 See how good your quote can be. At TD Insurance Meloche Monnex, we know how important it is to save wherever you can. As a member of the Trent University Alumni Association, you can enjoy preferred group rates on your home and auto insurance and other exclusive privileges, thanks to our partnership with your association. You’ll also benefit from great coverage and outstanding service. We believe in making insurance easy to understand so you can choose your coverage with confidence. Get an online quote at www.melochemonnex.com/trent or call 1-866-352-6187 Monday to Friday, 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Saturday, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Insurance program recommended by The TD Insurance Meloche Monnex home and auto insurance program is underwritten by SECURITY NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY. The program is distributed by Meloche Monnex Insurance and Financial Services Inc. in Quebec and by Meloche Monnex Financial Services Inc. in the rest of Canada. Due to provincial legislation, our auto insurance program is not offered in British Columbia, Manitoba or Saskatchewan. *No purchase required. Contest organized jointly with Primmum Insurance Company and open to members, employees and other eligible persons belonging to employer, professional and alumni groups which have an agreement with and are entitled to group rates from the organizers. -

The Role of Multilateral Intervention to Restore Local Justice Systems Final Report - December 1995

States Without Law: The Role of Multilateral Intervention to Restore Local Justice Systems Final Report - December 1995 A Seminar Organized by the Canadian Committee for the 50th Anniversary of the United Nations and The International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy at Green College, University of British Columbia States Without Law: The Role of Multilateral Intervention to Restore Local Justice Systems From Cambodia to Rwanda to the former Yugoslavia to Haiti, a key component of post-conflict peace-building is the re-establishment of governmental and legal structures. For states emerging from war, both a functioning government and a credible justice system are essential to ensuring that societies do not slip back into conflict. Increasingly, United Nations peace missions are taking on these peace-building responsibilities. In the space of a few short years, the world has moved from traditional peace-keeping, which was expected to do little but separate warring factions to allow breathing space for negotiations, to complex humanitarian interventions where the UN and the broader international community have become enmeshed in all of the machinery of government. And as the major UN interventions of the past five years have bluntly demonstrated, the United Nations is travelling up a steep learning curve as it seeks to help societies re-build themselves. At the University of British Columbia on December 9, 1995, a broad array of legal and strategic thinkers focussed their attention on the role of the international community in restoring order to conflict-wracked societies or "failed states." As one speaker after another pointed out, the old idea that peace-keepers and aid agencies can march into conflict situations, stop the fighting and the bleeding, and march out again is painfully outdated.