Universita' Degli Studi Di Padova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regione Toscana Giunta Regionale

Regione Toscana Giunta regionale Principali interventi regionali a favore del Valdarno Anni 2015-2020 Bucine Castelfranco Piandiscò Cavriglia Laterina Pergine Valdarno Loro Ciuffenna Montevarchi San Giovanni Valdarno Terranuova Bracciolini Direzione Programmazione e bilancio Settore Controllo strategico e di gestione Settembre 2020 1 INDICE ORDINE PUBBLICO E SICUREZZA .................................................................................................. 3 SISTEMA INTEGRATO DI SICUREZZA URBANA ..................................................................................................... 3 ISTRUZIONE E DIRITTO ALLO STUDIO .......................................................................................... 3 TUTELA E VALORIZZAZIONE DEI BENI E DELLE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI .......................................... 3 POLITICHE GIOVANILI, SPORT E TEMPO LIBERO .......................................................................... 4 SPORT E TEMPO LIBERO .................................................................................................................................... 4 GIOVANI ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 TURISMO ........................................................................................................................................ 4 SVILUPPO E VALORIZZAZIONE DEL TURISMO..................................................................................................... -

(Tuscany, Italy) Area

BOLLETTINO DI GEOFISICA TEORICA ED APPLICATA VOL. 45, N. 1-2, PP. 35-49; MAR.-JUN. 2004 Between Tevere and Arno. A preliminary revision of seismicity in the Casentino-Sansepolcro (Tuscany, Italy) area V. C ASTELLI Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Milano, Italy (Received December 2, 2003; accepted April 27, 2004) “An ill-favoured thing sir, but mine own.” (Wm. Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act V, Sc. 4) Abstract - According to the current Italian catalogue only a few minor earthquakes are located in the Tuscan portion of the Apennines lying between the seismogenic areas of Mugello (north) and Upper Valtiberina (south) and roughly corresponding to the historical district of Casentino. The existence of a seismic gap in this area has been conjectured but, as there is no definite geological explanation for a lack of energy release, the gap could also be an information one, due either to a lack of sources recording past earthquakes or even to a lack of previous seismological studies specifically dealing with the Casentino. A preliminary historical investigation improves the perception of local seismicity by recovering the memory of a few long-forgotten earthquakes. 1. Introduction The Casentino is a historical Tuscan district defined by the upper courses of the rivers Arno and Tevere; it includes a wide valley, through which the Arno flows in its earliest tract and which is bordered westward by the Pratomagno hill range and eastward by a section of the Apennines chain reaching southward to Sansepolcro and the Upper Valtiberina (Fig. 1). Though the Casentino lies between two well-known seismogenic areas (Mugello and Upper Valtiberina) no important earthquakes are located there according to the current Italian catalogue (Gruppo di Lavoro CPTI, 1999); the area is believed to be an obscure trait of the so-called Etrurian Fault System (Lavecchia et al., 2000) and the existence of a Casentino seismic gap was also Corresponding author: V. -

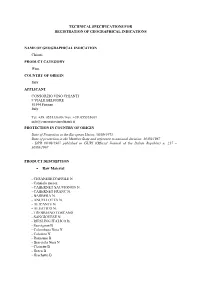

Technical Specifications for Registration of Geographical Indications

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS NAME OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION Chianti PRODUCT CATEGORY Wine COUNTRY OF ORIGIN Italy APPLICANT CONSORZIO VINO CHIANTI 9 VIALE BELFIORE 50144 Firenze Italy Tel. +39. 055333600 / Fax. +39. 055333601 [email protected] PROTECTION IN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN Date of Protection in the European Union: 18/09/1973 Date of protection in the Member State and reference to national decision: 30/08/1967 - DPR 09/08/1967 published in GURI (Official Journal of the Italian Republic) n. 217 – 30/08/1967 PRODUCT DESCRIPTION Raw Material - CESANESE D'AFFILE N - Canaiolo nero n. - CABERNET SAUVIGNON N. - CABERNET FRANC N. - BARBERA N. - ANCELLOTTA N. - ALICANTE N. - ALEATICO N. - TREBBIANO TOSCANO - SANGIOVESE N. - RIESLING ITALICO B. - Sauvignon B - Colombana Nera N - Colorino N - Roussane B - Bracciola Nera N - Clairette B - Greco B - Grechetto B - Viogner B - Albarola B - Ansonica B - Foglia Tonda N - Abrusco N - Refosco dal Peduncolo Rosso N - Chardonnay B - Incrocio Bruni 54 B - Riesling Italico B - Riesling B - Fiano B - Teroldego N - Tempranillo N - Moscato Bianco B - Montepulciano N - Verdicchio Bianco B - Pinot Bianco B - Biancone B - Rebo N - Livornese Bianca B - Vermentino B - Petit Verdot N - Lambrusco Maestri N - Carignano N - Carmenere N - Bonamico N - Mazzese N - Calabrese N - Malvasia Nera di Lecce N - Malvasia Nera di Brindisi N - Malvasia N - Malvasia Istriana B - Vernaccia di S. Giminiano B - Manzoni Bianco B - Muller-Thurgau B - Pollera Nera N - Syrah N - Canina Nera N - Canaiolo Bianco B - Pinot Grigio G - Prugnolo Gentile N - Verdello B - Marsanne B - Mammolo N - Vermentino Nero N - Durella B - Malvasia Bianca di Candia B - Barsaglina N - Sémillon B - Merlot N - Malbech N - Malvasia Bianca Lunga B - Pinot Nero N - Verdea B - Caloria N - Albana B - Groppello Gentile N - Groppello di S. -

Valdarno Vivi La Toscana Più Vera Valdarno Experience Genuine Tuscany

Toscana Valdarno vivi la Toscana più vera Valdarno Experience genuine Tuscany L’ambito turistico Visit Valdarno è formato da: www.visitvaldarno.com The Visit Valdarno tourist area is composed of the following municipalities: Comune Comune Comune Comune di Castelfranco di Laterina di Bucine di Cavriglia Piandiscò Pergine Valdarno Comune Comune Comune Comune di Loro di San Giovanni di Terranuova di Montevarchi Ciuffenna Valdarno Bracciolini www.visitvaldarno.com Con il patrocinio di: With the patronage of: Da non perdere in Valdarno Valdarno’s unmissable top ten 1 I sentieri in collina 2 Gropina e le pievi 3 Lo straordinario e montagna romaniche della strada olio extravergine Setteponti di oliva 4 Le Balze 5 Galatrona e i castelli 6 L’Annunciazione del Beato medievali sulle colline Angelico e i capolavori del Rinascimento 1 Walks in the hills and mountains 2 Gropina and the Romanesque parish churches along the Setteponti road 3 The extraordinary extra virgin olive oil 4 Le Balze 5 Galatrona and the medieval hilltop castles 6 The Annunciation by Beato Angelico and Renaissance masterpieces 7 Authentic Tuscan country cuisine 8 Valdarno di Sopra DOC wines and the wine cellars 9 The mammoth and other incredible animals in the Paleontological Museum 10 Palazzo d’Arnolfo and the Terre Nuove founded by Florence in the 7 L’autentica cucina toscana 8 La Valdarno di Sopra 9 Il Mammuth 10 Palazzo d’Arnolfo Middle Ages di campagna DOC e le cantine del vino e gli incredibili animali e le Terre Nuove fondate del Museo Paleontologico da Firenze nel Medioevo 2 3 Le Balze Le Balze - Le Balze ↑ Valdarno, vivi la Toscana più vera Valdarno, experience genuine Tuscany “ 4 “ Valdarno vivi la Toscana più vera “ “ Valdarno, Experience genuine Tuscany 5 e colline e la montagna, il fiume Arno, la campagna toscana autentica, il Pratomagno L e i Monti del Chianti, i poderi e le fattorie, il buon cibo toscano, le tante esperienze all’aria aperta, il relax in famiglia, l’arte, il buon vivere. -

Pergine Valdarno Arezzo

Pergine Valdarno Arezzo Pergine Arezzo Asking price:€ 1.250.000 A delightful property comprising main house, guest house and a further 3 annexes set in the rolling hills north-west of Arezzo. Surrounded by its own land, the property is accessed by a well-maintained track through fields and olive groves, past one other property. 4 Bedrooms • 4 Bathrooms • Separate guest accommodation • 2 annexes • Salt-wáter swimming pool Total land área:35 Ha; total floor space: 510 sq m (all measurements are approximate) Pergine Valdarno 10km • Arezzo 20km • Siena 57km • Florence 62km • Pisa International Airport 140km (all distances are approximate) Bought in 1995 and restored by the current owners, the main house on two floors of ca. 250 sqm has a lower ground floor with terrace leading to a lovely country kitchen with gas/wood oven, a dining room, a guest washroom, study, bedroom and bathroom. There is a pantry/laundry room to the rear. Upstairs there is a double living room with wonderful wood-burning stove. 2 bedrooms and a bathroom and a guest bathroom. The ceilings are lime-washed and the floors parquet, giving a warm and light atmosphere to the whole house. There is a charming dining loggia just off the kitchen. The guest house of ca. 80 sqm is set below the main house and has been restored to provide independent accommodation with its own entrance drive, a loggia into the kitchen with wood-burning stove, stairs to living room, bedroom and bathroom. Next to this house is an agricultural annexe with an oven of ca. -

Official Journal C 337 Volume 37 of the European Communities 1 December 1994

ISSN 0378-6986 Official Journal C 337 Volume 37 of the European Communities 1 December 1994 English edition Information and Notices Notice No Contents Page I Information Council 94/C 337/01 Council notice 1 Commission 94/C 337/02 Ecu 2 94/C 337/03 Average prices and representative prices for table wines at the various marketing centres 3 94/C 337/04 Notice to the Member States establishing the list of areas for assistance in the framework of a Community initiative concerning the economic conversion of coal mining areas (Rechar II) 4 EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AREA EFTA Surveillance Authority 94/C 337/05 Notice pursuant to Article 19 (3) of Chapter II of Protocol 4 to the Agreement between the EFTA States on the establishment of a Surveillance Authority and Court of Justice concerning Case No COM 0006 — Metsäteollisuus Ry — Skogs industrin Rf and Case No COM 0105 — Maa- ja metsataloustuottajain Keskusliitto MTK ry 21 1 (Continued overleaf) Notice No Contents (continued) Page II Preparatory Acts Council 94/C 337/06 Assent No 30/94 given by the Council, acting unanimously pursuant to the second paragraph of Article 54 of the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, for the granting of a global loan to Mediocredito Centrale, Rome (Italy) to finance investment programmes which contribute to facilitating the marketing of Community steel 23 III Notices Commission 94/C 337/07 Amendment to notice of invitation to tender for the refund for the export of milled medium-grain and long-grain A rice to certain third countries 24 94/C 337/08 -

Policy Committee

COUNCIL OF EUROPEAN MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS EUROPEAN SECTION OF UNITED CITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS POLICY COMMITTEE Reykjavik, 5 May 2008 ACCOMPANYING DOCUMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page n° Draft European Charter of Regional Democracy (at 13.3.08) .................................................. 3 Supporting documentation to nominations received for the new Chair of the twinning network ......................................................................................... 17 CEMR's response to the Green Paper on adaptation to climate change ............................... 21 CEMR's response to the Green Paper on urban mobility ....................................................... 35 CEMR’s response to the Public Consultation on the Active Inclusion of People Furthest from the Labour Market ................................................................................ 47 CEMR's response to the consultation on the future of EU cohesion policy ............................ 55 List of signatories of the European Charter for Equality of Women and Men in Local Life (at 17th April 2008) ................................................................. 61 VNG/Municipal Alliance for Peace detailed proposal for strengthening and institutionalisation of MAP ........................................................................ 67 Euro-Arab Cities Forum, Dubai (10-11 February), report and final declaration ...................... 71 2 The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities APPENDIX Draft European Charter of Regional Democracy (version -

Atti Società Toscana Scienze Naturali

ATTI DELLA SOCIETÀ TOSCANA DI SCIENZE NATURALI MEMORIE • SERIE B • VOLUME CXXVII • ANNO 2020 Edizioni ETS INDICE - CONTENTS A. BERTACCHI, D. BORGIA – Paesaggio forestale e incendi R. MENCACCI, Y. POZO-GALVAN, C. CARUSO, P. LUSCHI – in aree forestali del Monte Pisano: il caso di studio della Long-range movements of the first oceanic-stage log- Valle di Crespignano (PI) - Toscana nord-occidentale. gerhead turtle tracked in Italian waters. Forest landscape and fires in forested areas of Monte Movimenti a lungo raggio in acque italiane di una tar- Pisano: the case study of Crespignano Valley (Pisa, NW taruga comune in fase oceanica. » 79 Tuscany, Italy) pag. 5 A. MISURI, G. FERRETTI, L. LAZZARO, M. MUGNAI, R. CANOVAI – Contributo alla conoscenza dei Cocci- D. VICIANI – Investigations on ecology and distribu- nellidi (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae) del Parco Regionale tion of Senecio inaequidens DC. (Asteraceae) in Tus- della Maremma (Toscana). cany (Italy). Contribution to the knowledge of ladybirds (Coleoptera Ricerche su ecologia e distribuzione di Senecio inaequi- Coccinellidae) of the Maremma Regional Park (Tusca- dens DC. in Toscana. » 85 ny, Italy). » 21 L. PERUZZI et al. – Contributi per una flora vascolare M. IANNIBELLI, D. MUSmaRRA, A. AIESE – Comunità di Toscana. XII (739-812). bentoniche di un’area costiera del Tirreno (Agropoli, Contributions for a vascular flora of Tuscany. XII Salerno). (739-812). » 101 Benthic communities of a Thyrrenian sea coastal area (Agropoli, Salerno). » 29 C. RUSSO, F. CECCHI, P.A. ACCORSI, N. SCampUddU, M.N. BENVENUTI, L. GIULIOTTI – Investigation on E. DEL GUACCHIO, A. DE NATALE, A. STINCA – Notes sheep farm characteristics, wolf predation and animal to the non-native flora of Campania (Southern Italy). -

Pergine Valdarno Arezzo

Pergine Valdarno Arezzo Pergine Arezzo Asking price:€ 1.250.000 A delightful property comprising main house, guest house and a further 3 annexes set in the rolling hills north-west of Arezzo. Surrounded by its own land, the property is accessed by a well-maintained track through fields and olive groves, past one other property. 4 Bedrooms • 4 Bathrooms • Separate guest accommodation • 2 annexes • Salt-wáter swimming pool Total land área:35 Ha; total floor space: 510 sq m (all measurements are approximate) Pergine Valdarno 10km • Arezzo 20km • Siena 57km • Florence 62km • Pisa International Airport 140km (all distances are approximate) Bought in 1995 and restored by the current owners, the main house on two floors of ca. 250 sqm has a lower ground floor with terrace leading to a lovely country kitchen with gas/wood oven, a dining room, a guest washroom, study, bedroom and bathroom. There is a pantry/laundry room to the rear. Upstairs there is a double living room with wonderful wood-burning stove. 2 bedrooms and a bathroom and a guest bathroom. The ceilings are lime-washed and the floors parquet, giving a warm and light atmosphere to the whole house. There is a charming dining loggia just off the kitchen. The guest house of ca. 80 sqm is set below the main house and has been restored to provide independent accommodation with its own entrance drive, a loggia into the kitchen with wood-burning stove, stairs to living room, bedroom and bathroom. Next to this house is an agricultural annexe with an oven of ca. -

Presentazione Pergine Laterina

- Intro istituzionale : iter - Studio di omogeneità Comune di Comune di Laterina Pergine Valdarno 1 Comuni di Laterina e Pergine Valdarno Comuni classificati in base alla popolazione residente. Anno 2016 Densità Popolazione Superficie abitativa, Comune 2016 km2 abitanti per km2 Bucine 10.164 131,47 77,3 Castiglion Fibocchi 2.167 25,46 85,1 Civitella in Val di Chiana 9.121 100,19 91,0 Laterina 3.517 24,05 146,2 Pergine Valdarno 3.162 46,52 68,0 Terranuova Bracciolini 12.346 85,88 143,8 Arezzo 99.543 384,7 258,8 Popolazione Superficie Densità abitativa, Comune 2016 km2 abitanti per km2 Ipotesi comune unico Laterina Pergine Valdarno 6.679 70,57 94,6 • Insieme Laterina e Pergine raggiungono una popolazione complessiva di 6.679 abitanti, facendo un “salto” di classe dimensionale. 2 Le fusioni di comuni in Toscana 22 Referendum svolti di cui 11 esito positivo + 4 Ipotesi Referendum ad Ottobre 2017 ( presumibilmente il 29 e 30 ott.) 3 L’iter legislativo 3 FASI DEL PROCESSO DECISIONALE “La Regione, sentite le popolazioni interessate, può con sue leggi istituire nel proprio territorio nuovi Comuni e modificare le loro circoscrizioni e denominazioni” ( art.133 – Costituzione) 1- 2 3 Iniziativa Consultiva Decisoria (proposta di legge) (referendum) (legge di fusione) 4 1 – Iniziativa legislativa • Cittadini art. 74 Statuto R.T Iniziativa popolare può essere • Consiglieri regionali art. 59 L.r. 62/07 esercitata da almeno il 25 per cento La commissione consiliare competente degli elettori iscritti nelle liste elettorali acquisisce parere dai consigli comunali del medesimo comune (se inferiore a interessati entro 30 giorni 5.000) • CONSIGLI COMUNALI art. -

Posticcia Nuova € 2.950.000

Ref. 1861 – POSTICCIA NUOVA € 2.950.000 Pergine Valdarno – Florence – Tuscany www.romolini.co.uk/en/1861 Interiors Bedrooms Bathrooms Swimming pool 611 mq 5 7 14 × 5 m Land Olive grove Oil 15,7 ha 1,550 trees 11,0 hl This estate includes a 17th-century Tuscan villa, a few outbuildings, a swimming pool and an am- ple olive grove. The villa is surrounded by an elegant garden decorated with walkways and flow- ers. The property includes about 15.7 hectares of land, of which 8.2 ha of woodland and an olive grove with 1,550 trees. The average yearly production of organic extra-virgin oil is 11 hl. © Agenzia Romolini Immobiliare s.r.l. Via Trieste n. 10/c, 52031 Anghiari (AR) Italy Tel: +39 0575 788 948 – Fax: +39 0575 786 928 – Mail: [email protected] REFERENCE #: 1861 – POSTICCIA NUOVA TYPE: Tuscan estate with 17th-century villa, pool, olive grove and outbuildings CONDITIONS: restored LOCATION: hilly, panoramic MUNICIPALITY: Pergine Valdarno PROVINCE: Arezzo REGION: Tuscany INTERIORS: 611 square meters (6,573 square feet) TOTAL ROOMS: 21 BEDROOMS: 5 BATHROOMS: 7 MAIN FEATURES: terracotta floors, wooden beams, vaulted ceilings, arches, stone fireplace, stone staircase, portico, loggia, Infinity swimming pool, olive grove, two separate guest accommo- dation buildings LAND: 15.7 hectares (8.2 ha woodland + 4.6 ha olive grove + 2.9 ha arable land) GARDEN: yes, very well-maintained ANNEXES: several buildings ACCESS: elegant cypress-lined avenue SWIMMING POOL: 14 × 5 m (Infinity) ELECTRICITY: already connected (energy class G) WATER SUPPLY: already -

VILLA MONSOGLIO BROCHURE ENG Parte 1.Cdr

HISTORY LUXURY EXCLUSIVITY HISTORY LUXURY EXCLUSIVITY T H E N A N D N O W Perhaps it was a desire to enhance and hand-down a house and estate that is so ex-traordinary that Leonardo da Vinci painted it in the background of the Mona Lisa. Or, maybe, he wanted to be part of a history that included some of the most famous Flor- entine families such as the Peruzzi, bankers and merchants of the Guelph faction, or the Capponis and their famous son Gino the most renowned member of the family who was an intimate friend of the writers, Ugo Foscolo, Alessandro Manzoni and Giacomo Leopardi. Together with my family and those who are helping me in this venture, I wanted envision a different future for Villa Monsoglio. A future that would be interesting and at the same time respectful of the villa’s artistic features in terms of their uniqueness, heritage and beauty. On the one hand, all of us are becoming more and more aware of the fact that conserving the cultural heritage is essential for developed societies, on the other, there is the need to revitalize and freshen up the beauty of something that cannot be locked up in a cabinet. It was precisely for these reasons that, in January 2015 I began building the future of Villa Monsoglio, piece by piece, according to a plan that would give it a definitive boost. “Events in Tuscany” is the phrase I chose for the new logo – Villa Monsoglio – redesigned and enriched with a symbolic component.