Golden Blade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forum Antroposofi

Forum Antroposofi nr 2 2o17 forum för antroposofi nr 2 2o17 perspektivet 4–5 21–24 Notiser. Reflektioner: Tillit och mod i En reflektion från årsmötet. 6–9 Uppgift. en orolig tid Samtal: Sanning. Mats-Ola Ohlsson Fria Högskolan för Antroposofi. Vad händer kring 72-års åldern? Meditera? Den senaste tiden har varit präglad av na för mänskligheten är hat och fruktan. mor till två barn bar dem mellan bomb- många händelser som kan skapa oro och Därför har vi alla ett ansvar att stå sam- krevader genom de gamla stadskvarteren 24–25 förvirring hos många människor. Osäker- lade för att rättvisa, jämlikhet och fred ska i krigets slutskede. Och hon berättade vi- het präglar det politiska livet och det tar gälla alla människor. Även om en tragedi dare hur familjen hade fått hålla hemligt 1o–15 Till minne. sig uttryck i nationalistiska/separatistiska kan inträffa så är det det som kan rädda för nationalsocialisterna att de var antro- tendenser, här i vårt närområde och in- oss. …Idén om att hålla människor åtskil- posofer, om hur de fick mötas i hemlighet Krönikor: Levnadsteckningar. ternationellt. Grupper av människor står da på grund av rädsla får inte fäste om vi och gömma böcker för att de inte skulle emot varandra, en förståelse saknas ofta kan skapa mötesplatser där människor brännas upp i bokbålen. Hon delade med Integrativ medicin. Bokanmälan: Maria-Sofia. för det som förenar, utan man söker det kan erfara att de kan leva tillsammans och sig av ett meditationsspråk av Rudolf Stei- som slår split. Relationen till naturen och påbörja försoningsprocesser. -

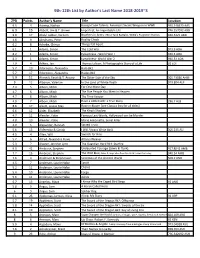

9Th-12Th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S

9th-12th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 9.5 4 Aaseng, Nathan Navajo Code Talkers: America's Secret Weapon in WWII 940.548673 AAS 6.9 15 Abbott, Jim & T. Brown Imperfect, An Improbable Life 796.357092 ABB 9.9 17 Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Brothers in Arms: 761st Tank Battalio, WW2's Forgotten Heroes 940.5421 ABD 4.6 9 Abrahams, Peter Reality Check 6.2 8 Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart 6.1 1 Adams, Simon The Cold War 973.9 ADA 8.2 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness - World War I 940.3 ADA 8.3 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness- World War 2 940.53 ADA 7.9 4 Adkins, Jan Thomas Edison: A Photographic Story of a Life 92 EDI 5.7 19 Adornetto, Alexandra Halo Bk1 5.7 17 Adornetto, Alexandra Hades Bk2 5.9 11 Ahmedi, Farah & T. Ansary The Other Side of the Sky 305.23086 AHM 9 12 Albanov, Valerian In the Land of White Death 919.804 ALB 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For One More Day 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper 4.9 7 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: a True Story 296.7 ALB 8.6 17 Alcott, Louisa May Rose in Bloom [see Classics lists for all titles] 6.6 12 Alder, Elizabeth The King's Shadow 4.7 11 Alender, Katie Famous Last Words, Hollywood can be Murder 4.8 10 Alender, Katie Marie Antoinette, Serial Killer 4.9 5 Alexander, Hannah Sacred Trust 5.6 13 Aliferenka & Ganda I Will Always Write Back 305.235 ALI 4.5 4 Allen, Will Swords for Hire 5.2 6 Allred, Alexandra Powe Atticus Weaver 5.3 7 Alvarez, Jennifer Lynn The Guardian Herd Bk1: Starfire 9.0 42 Ambrose, Stephen Undaunted Courage -

A Window on Nature Stirring the Biodynamic Preparations Jimmy

Journal of the Biodynamic agricultural association n ISSUE NO: 112 n WINTER 2010 n ISSN NO: 1472-4634 n £4.50 harnessing the energy of the soil chromas - a window on nature stirring the Biodynamic preparations Jimmy anderson - in conversation the Biodynamic seed development project STAR & FURROW agricultural The Association is working to develop a sus- Journal of the Biodynamic Agricultural Association association (BDAA) tainable on-farm plant breeding programme, Published twice yearly increase the availability of high quality seed Issue Number 112 - Winter 2010 The Association exists in order to sup- varieties suited to organic growing condi- ISSN 1472-4634 port, promote and develop the biodynamic tions and encourage the establishment of approach to farming, gardening and forestry. a cooperative network of biodynamic seed This unique form of organic growing seeks producers. The breeding and development of STAR & FURROW is the membership magazine to improve the nutritional value of food and appropriate site adapted varieties is of vital of The Biodynamic Agricultural Association the sustainability of land by nurturing the vi- interest to biodynamic farmers and offers (BDAA). It is issued free to members. tality of the soil through the practical applica- the only long term alternative to biotech- Non members can also purchase Star and tion of a holistic and spiritual understanding nology. It also requires an ongoing research Furrow. For two copies per annum the rates are: of nature and the human being. Put simply, commitment that is entirely dependent on UK £11.00 including postage our aim is greater vitality for people and gifts and donations. -

Information for Pros

160/2012 World of PORR Information for pros World of PORR 160/2012 Table of contents Table of contents Foreword CEO Karl-Heinz Strauss Page 4 PORR Projects Renovation and widening of the Aabachtal Viaduct at Lenzburg, Switzerland A challenge in terms of technology and traffic Page 5 Gasgasse housing complex and students' residence The PORR Group built a cooperative housing complex with 265 government-subsidised apartments and a students’ residence in Vienna’s 15th district. Page 10 Resurfacing and repair of A2 motorway (Südautobahn), section Ilz–Sinabelkirchen Replacement of asphalt pavement and bridge repair on an 8-km stretch of motorway Page 13 Seminar hotel Schloss Untermerzbach Construction of a new hotel building and extensive renovation of the existing historic building Page 15 Surgical Ward West II, Salzburg Alterations and additions to the existing buildings to create one of the most modern hospitals in Central Europe Page 18 The Simmering Residential Care Facility A home for 348 residents with special nursing care needs Page 22 Flood control at Rossatz/Wachau Extensive engineering works to protect local inhabitants against the constant threat of flooding Page 29 HPP Ashta Hydropower plants in Albania Page 31 Revitalising the main building of BBRZ Reha GmbH in Linz New visual identity for the vocational training and rehabilitation centre Page 39 Rehabilitation works on A1 motorway (Westautobahn) Extensive repairs on Auhof access/exit section Page 44 New construction replaces Achbrücke railway bridge, Tyrol Elegant bridge design -

Morality and Ethics in Education

Waldorf Journal Project #10 April 2008 AWSNA Morality and Ethics in Education #1 Compiled and edited by David Mitchell “Reverence for life affords me my fundamental principle of morality, namely that good consists in maintaining, assisting, and enhancing life, and that to destroy, to harm, or to hinder life is evil” —Albert Schweitzer Waldorf Journal Project #10 April 2008 AWSNA Morality and Ethics in Education #1 Printed with support from the Waldorf Curriculum Fund Published by: AWSNA Publications The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America 65-2 Fern Hill Road Ghent, NY 12075 © 2008 byAWSNA Publications Waldorf Journal Project #10 Title: Morality and Ethics in Education #1 Translators: Ted Warren, Jan-Kees Saltet, Jon McAlice, Karin Di Giacomo Editor: David Mitchell Proofreader: Ann Erwin Gratitude is expressed to the editors of Steinerskolen and the individual authors for granting permissions to translate the essays for North America. contEnts Foreword ............................................................................................ 7 Education and the Moral Life by Rudolf Steiner ......................................................................... 9 Education of the Will as the Wellspring of Morality by Michaela Glöckler ................................................................... 13 Human Development and the Forces of Morality by Ernst-Michael Kranich............................................................ 23 Conscience and Morality by Karl Brodersen ....................................................................... -

PDF-Download

Schweiz Suisse Svizzera Svizra X – 2020 Mitteilungen aus dem anthroposophischen Leben Nouvelles de la vie anthroposophique Notiziario della vita antroposofica Anthroposophie L’Anthroposophie übernimmt Verantwortung prend ses responsabilités Feier zum 100-Jahr-Jubiläum der Fête pour le jubilé des 100 ans de la Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft in der Schweiz Société anthroposophique suisse Sonntag, 25. Oktober 2020, 10 bis 18 Uhr Dimanche 25 octobre 2020, de 10 à 18 heures im Zelt Station Circus, Münchensteinerstrasse 103, 4053 Basel Station Circus, Münchensteinerstrasse 103, 4053 Bâle (Tram 10/11, Haltestelle M-Parc) (Tram 10/11, arrêt M-Parc) Programm Programme Einstimmung mit Musik, 10:00 Introduction avec musique, Antipe da Stella, Flöte; Antipe da Stella, flûte; Milena Kowarik, Cello Milena Kowarik, violoncelle Begrüssung, Marc Desaules 10:10 Accueil, Marc Desaules Peter Selg: Peter Selg: Die Aktualität des Vergangenen, La pertinence du passé, les conférences Rudolf Steiners Schweizer Vorträge 1920 – suisses 1920 de Rudolf Steiner – und die heutige Lage et la situation actuelle Pause 11:00 Pause Marc Desaules: 11:30 Marc Desaules: Der Impuls der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft L’impulsion de la Société anthroposophique suisse in der Schweiz mit dem FondsGoetheanum avec le FondsGoetheanum pour soutenir zur Unterstützung der anthroposophischen le travail anthroposophique dans les différents Arbeit in den verschiedenen Lebensfeldern domaines de la vie Danielle Lemann: 12:00 Danielle Lemann: Die Anthroposophische Medizin in La médecine anthroposophique à une gesundheitskritischer Zeit époque critique pour la santé Johannes Wirz: 12:30 Johannes Wirz: Anthroposophische Ansätze zur Heilung Approches anthroposophiques de la guérison und Erhaltung der Bienen et de la protection des abeilles Mittagessen: 13:00 Repas de midi: Restauarant Tibits, Bhf SBB, Restauarant Tibits, gare CFF, Hinterausgang (inkl. -

Understanding Young Children

UNDERSTANDING YOUNG CmLDREN EXCERPTS FROM LECTURES BY RUDOLF STEINER COMPILED FOR TIlE USE OF KINDERGARTEN TEACHERS Published by the International Association of Waldorfkindergartens, Stuttgart, 1975 Reprinted 1994 by the Waldorf Kindergarten Association of North America, Inc. Copies available from the Waldorf Kindergarten Association 1359 Alderton Lane SHver Spring, MD 20906 (301) 460-6287 Permission to duplicate these excerpts has been given by: The Rudolf Steiner NachlaBverwaltung, the Library of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain and the Rudolf Steiner Press, London INTRODUCTION 1bB book is meant to be a help for those working in Kindergartens founded on the educational prila;iples of Rudolf Steiner. All the parents of little children, students and friends of Waldorf Education who are interested in a deeper understanding of child development will find in this book guide lines for The Study oj Man. It was Elizabeth Grunelius who first suggested compiling the following excerpts from Rudolf Steiner's books and lectures. Already in the early twenties she asked Rudolf Steiner for suggestions on pre-school education, and founded the very first Waldorf Kindergarten in Stuttgart. We are happy to publish this collection in time for the 50th anniversary of Waldorf education in England. It is advisable to read the quoted passages in the context of the whole lecture. Unfortunately some of Rudolf Steiner's lectures on education have not yet been translated. The books and lectures we quote have all been translated into English. Other books about the education of the child are: • Francis Edmunds, Rudolf Steiner Education: The Waldorf Schools, Rudolf Steiner College Press and Rudolf Steiner Press. -

Goldenblade 1986.Pdf

The Golden Blade THIRTY-EIGHTH (1986) ISSUE CONTENTS E d i t o r i a l N o t e s 3 The Rejoicing Eye Doris Davy 10 The Earth Seen by the Dead Rudolf Steiner 13 The Mystery of Mary - In Body, Soul and Spirit Emil Bock 17 The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air We Breathe Gerard Manley Hopkins 36 T h e P l i g h t o f O u r F o r e s t s M a r k R i e g n e r 4 0 Food, Famine, Misery and Hope Daniel T Jones 56 Ethiopia — Nightmare or Paradise? Tim Cahiil-O'Brien 64 The British Countryside 1985-2050 John Soper 68 The Daily Bread Michael Spence 73 Karo Bergmann - Art as a Healing Force for our Times Monika Hertrampf-Pickmann 80 "The Three Spheres of Society" - The History of a Pioneering ^ 0 0 * ^ C h a r l e s D a v y 9 1 B e t w e e n t h e P o l e s C h a r l e s D a v y 9 3 Genesis Josephine Spence 97 N o t e s a n d A c k n o w l e d g e m e n t s 9 8 Edited by Adam Bittleston, Daniel T. Jones and John Meeks EDITORIAL NOTES BeforeDavy the in onset October of the1984, illness the whicheffectiveness brought of abouthis work the for death a considerable of John public, for the Anthroposophical Society, for Emerson College, and throu^ many conversations with individuals, was steadily growing. -

" Dragon Tales." 1992 Montana Summer Reading Program. Librarian's Manual

-DOCUMENT'RESUME------ ED 356 770 IR 054 415 AUTHOR Siegner, Cathy, Comp. TITLE "Dragon Tales." 1992 Montana Summer Reading Program. Librarian's Manual. INSTITUTION Montana State Library, Helena. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 120p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reference Arterials Bibliographies (131) Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Braille; *Childrens Libraries; *Childrens Literature; Disabilities; Elementary Education; Games; Group Activities; Handicrafts; *Library Services; Program Descriptions; Public Libraries; *Reading Programs; State Programs; Story Telling; *Summer Programs; Talking Books IDENTIFIERS *Montana ABSTRACT This guide contains a sample press release, artwork, bibliographies, and program ideas for use in 1992 public library summer reading programs in Montana. Art work incorporating the dragon theme includes bookmarks, certificates, reading logs, and games. The bibliography lists books in the following categories: picture books and easy fiction (49 titles); non-fiction, upper grades (18 titles); fiction, upper grades (45 titles); and short stories for easy telling (13 titles). A second bibliography prepared by the Montana State Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped provides annotations for 133 braille and recorded books. Suggestions for developing programs around the dragon and related themes, such as the medieval age, knights, and other mythic creatures, are provided. A description of craft projects, puzzles, and other activities concludes -

Report on Austrian Contributions to the Mab Programme for the Year 2012

Austrian MAB-Committee at the Austrian Academy of Sciences Chair: Univ.-Prof.Mag.Dr. Georg Grabherr Vice Chair: Univ.-Prof.Mag.Dr. Arne Arnberger Executive Secretary: Mag.Dr. Günter Köck c/o Austrian Academy of Sciences International Research Programmes Dr. Ignaz Seipel-Platz 2 1010 Vienna Austria Tel: +43 1 51581 1271 Fax: +43 1 51581 1275 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://www.oeaw.ac.at REPORT ON AUSTRIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE MAB PROGRAMME FOR THE YEAR 2012 1. NATIONAL COMMITTEE ACTIVITIES AND FUNDING: In 2012 two meetings of the Austrian National Committee for MAB took place. The managers of the Austrian biosphere reserves (BRs) joined the meetings and reported about activities in their area and discussed future research strategies with the committee members. One of the meetings was held as a two-day event in the Biosphere Reserve “Großes Walsertal” including consultations with high-level politicians stake-holder and inspections of community projects. For the year 2012 the total funding for MAB, provided by the Austrian Ministry for Science and Research, was EURO 150.000,- = US$ 195.276,-1 1 Exchange rate per 04/03/2013 This funding was entirely used for research projects. 2. FUNDING CONTRIBUTION TO UNESCO MAB Young Scientist Awards: In response to the need expressed by the MAB International Co-ordinating Council (MAB-ICC) regarding mobilization of extra-budgetary funding in context of the MAB Young Scientist Award Scheme, particularly to raise the number of awards the Austrian National Committee for MAB decided to contribute the amount of US$ 10,000 to finance two additional MAB Young Scientists Research Awards for the year 2012. -

Parigi E Il Quinto Vangelo

N.57 - 2020 ANTROPOSOFIA OGGI € 5,50 ParigiParigi ee ilil QuintoQuinto VangeloVangelo I disegni spontanei dei bambini POSTE ITALIANE S.P.A. - SPEDIZIONE IN ABBONAMENTO POSTALE AUT. N.0736 PERIODICO ROC DL.353/2003 (CONV.IN L.27/02/2004 N.46) ART.1 COMM1 I, DCB MILANO L.27/02/2004 N.46) ART.1 N.0736 PERIODICO ROC DL.353/2003 (CONV.IN AUT. - SPEDIZIONE IN ABBONAMENTO POSTALE S.P.A. POSTE ITALIANE Il calore dentro e fuori di noi Dalla Natura soluzioni efficaci per la salute e il benesserre di tutta la famiglia Rimedi sviluppati secondo i principi dell’’AAntroposofia, dal 19355 Per inffoormazioni: La cosmesi Dr. Hauschka è prodotta da wwww..drr..hauschka.com WWAALA ITTAALIA [email protected] WALA Heilmittel GmbH, Germania wwww..wala.it Via Fara, 28 - 20124 Milano [email protected] EDITORIALE Eravamo pronti per andare in stampa quando si è diffusa la notizia che l’Italia si trovava sfortunatamente in prima linea nella lotta al Coronavirus. È inquie- tante notare come si possano scatenare emozioni in una dimensione fino ad ora impensabile. Anche i medici sono più o meno concordi nell’affermare che si tratti di una sorta di influenza come ne abbiamo ogni anno e che spesso è causa di tanti problemi soprattutto per le persone anziane. Come siamo arrivati, quindi, a dare a questo virus le dimensioni di una pandemia di gravità tale che rischia di essere ingestibile, in quanto le strutture sanitarie risulterebbero inadeguate ma soprattutto sarebbero insufficienti? Fa paura questa grande fragilità della nostra società che potrebbe facilmente diventare una forza ma- nipolabile da influenze negative. -

KOERNER S HAVES by BUFFALO N Vv

; KOERNER S HAVES BY BUFFALO N Vv ! = \A #1 t : 4 ¢ Jack the Giant=Killer. The Giant Stepped on Jack’s Trap and Fell Headlong into the Pit. [° the days of the renowned King Arthur there lived a Cornishman named Jack, who was famous for his valiant deeds. His bold and warlike spirit showed itself in his boyish days; for Jack took especial delight in listening to the wonderful tales of giants and fairies, and of the extraordinary feats of valor displayed by the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table, which his father would sometimes relate. Jack’s spirit was so fired by these strange accounts, that he determined, if ever he became a man, that he would destroy some of the cruel giants who infested the land. Not many miles from his father’s house there lived, on the top of St. Michael’s Mount, a huge giant, who was the terror of the country round, who was named Cormoran, from his voracious appetite. It is said that he was eighteen feet in height. When he required food, he came down from his castle, and, seizing on the flocks of the poor people, would throw half a dozen oxen over his shoulders, and suspend as many sheep as he could carry, and stalk back to his castle. He had carried on these depredations many years ; and the poor Cornish people were well-nigh ruined. Jack went by night to the foot of the mount and dug a very deep pit, which he covered with sticks and straw, and over which he strewed the earth.