Rubato and Climax Projection in Two Piano Sonatas by Scriabin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

Seattle Symphony February 2018 Encore Arts Seattle

FEBRUARY 2018 LUDOVIC MORLOT, MUSIC DIRECTOR LISA FISCHER & G R A N D BATON CELEBRATE ASIA IT TAKES AN ORCHESTRA COMMISSIONS &PREMIERES CONTENTS EAP full-page template.indd 1 12/22/17 1:03 PM CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2018 4 / CALENDAR 6 / THE SYMPHONY 10 / NEWS FEATURES 12 / IT TAKES AN ORCHESTRA 14 / THE ESSENTIALS OF LIFE CONCERTS 15 / February 1–3 RACHMANINOV SYMPHONY NO. 3 18 / February 2 JOSHUA BELL IN RECITAL 20 / February 8 & 10 MORLOT CONDUCTS STRAUSS 24 / February 11 CELEBRATE ASIA 28 / February 13 & 14 LA LA LAND IN CONCERT WITH THE SEATTLE SYMPHONY 30 / February 16–18 JUST A KISS AWAY! LISA FISCHER & GRAND BATON WITH THE SEATTLE SYMPHONY 15 / VILDE FRANG 33 / February 23 & 24 Photo courtesyPhoto of the artist VIVALDI GLORIA 46 / GUIDE TO THE SEATTLE SYMPHONY 47 / THE LIS(Z)T 24 / NISHAT KHAN 28 / LA LA LAND Photo: Dale Robinette Dale Photo: Photo courtesyPhoto of the artist ON THE COVER: Lisa Fischer (p. 30) by Djeneba Aduayom COVER DESIGN: Jadzia Parker EDITOR: Heidi Staub © 2018 Seattle Symphony. All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without written permission from the Seattle Symphony. All programs and artists are subject to change. encoremediagroup.com/programs 3 ON THE DIAL: Tune in to February Classical KING FM 98.1 every & March Wednesday at 8pm for a Seattle Symphony spotlight and CALENDAR the first Friday of every month at 9pm for concert broadcasts. SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY ■ FEBRUARY 12pm Rachmaninov 8pm Symphony No. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations In

MYSTIC CHORD HARMONIC AND LIGHT TRANSFORMATIONS IN ALEXANDER SCRIABIN’S PROMETHEUS by TYLER MATTHEW SECOR A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Tyler Matthew Secor Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Jack Boss Chair Dr. Stephen Rodgers Member Dr. Frank Diaz Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Tyler Matthew Secor iii THESIS ABSTRACT Tyler Matthew Secor Master of Arts School of Music and Dance September 2013 Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis seeks to explore the voice leading parsimony, bass motion, and chromatic extensions present in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus. Voice leading will be explored using Neo-Riemannian type transformations followed by network diagrams to track the mystic chord movement throughout the symphony. Bass motion and chromatic extensions are explored by expanding the current notion of how the luce voices function in outlining and dictating the harmonic motion. Syneathesia -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

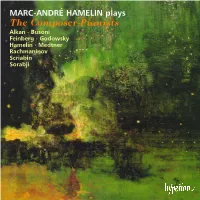

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN Plays the Composer-Pianists Alkan

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN plays The Composer-Pianists Alkan . Busoni Feinberg . Godowsky Hamelin . Medtner Rachmaninov Scriabin Sorabji HE RELATION between musical effect and the technical ‘encore’ repertoire; less convincingly as regards the latter half means necessary for its creation or recreation is apt to of a recital, which at one time might have been entirely Tbe one of opposites. The ‘Representation of Chaos’ with devoted to the type of confection indicated above. However, it which Haydn embarked on The Creation, for example, could can be said that the present offers the best of all liberal worlds, not have succeeded without a conspicuously well ordered in which deeply serious artists may leaven but not demean the compositional technique, nor could the percussion- and intellectual and spiritual weight of their mainstream reper- timpani-based anarchy of Nielsen’s Fourth and Fifth toire by restoring to public attention the full variety and zest of Symphonies or, indeed, the ‘controlled chance’ of more a once discredited milieu. In this connection the abstract recent, aleatory trends. A true chaos of means leads only to nature and importance of ‘pianism’ itself should be empha- incoherence, whereas an intended one of expressive ends may sized: for the serious performing artist the purely physical, be likened to the birth of a universe: explosive, precipitate, callisthenic dimension in Tausig, Rosenthal, Schulz-Evler, seemingly beyond all elemental control, and yet achieved with Scharwenka, Hoffman, Godowsky and others illumines the the pinprick accuracy of some infinitely magnified snowflake, nature of the instrument, and of the art itself, in myriad and defying our later scrutiny to find in it mere accident rather idiosyncratic ways. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

Steven Isserlis

Editor’s Lunch: STEVEN ISSERLIS For the Amati Magazine’s inaugural Editor’s Lunch, who better to entertain than the man who is arguably Britain’s greatest living cellist? Steven Isserlis joins Jessica Duchen for a Baltic feast by Jessica Duchen, 23 January 2015 Steven Isserlis and I have come to Southwark to find his roots. Culinary ones, at least: for Baltic , London’s leading Polish-plus restaurant in the shadow of the Shard, is rather nearer than Krakow. The founding father of the sizeable Isserlis dynasty was Moses Isserlis , a great Talmudic scholar whose 16 th -century synagogue is among the historic Polish city’s most fascinating destinations. “Along the way the family included Mendelssohn, Karl Marx, Helena Rubinstein and a few others,” Isserlis remarks, “and on my mother’s side we’re related to the composer Louis Lewandowski [the 19 th -century composer of synagogue music in Berlin]. There’s been music pouring through the family tree.” His sisters are both musicians: Rachel a violinist, Annette a violist and a vital member of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. They have all collaborated in producing a CD for Hyperion devoted to the music of their grandfather, the pianist and composer Julius Isserlis , performed by Sam Haywood. Baltic’s menu explores the broad cuisine of its eponymous region, enhanced by the skylit airiness of the atmosphere. The list of different vodkas has to be seen to be believed – more than 60 varieties, with many flavours home-made – and the possible eats even include potato latkes. Isserlis, post-festive season, has nevertheless specified that he’d like a healthy lunch (which wasn’t altogether what I had in mind) and when he bounces into Baltic, his silver curls unmistakable at the entrance, his will power is firmly in place. -

Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Paliy, Olga (2017) Taneyev’s Influence on Practice and Performance Strate- gies in Early 20th Century Russian Polyphonic Music. Doctoral thesis (PhD), awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by the Manchester Metropolitan University. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/626473/ Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk TANEYEV’S INFLUENCE ON PRACTICE AND PERFORMANCE STRATEGIES IN EARLY 20th CENTURY RUSSIAN POLYPHONIC MUSIC OLGA PALIY This thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by the Manchester Metropolitan University ROYAL NORTHERN COLLEGE OF MUSIC AND THE MANCHESTER METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY January 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Acknowledgments …….………………………………………………………….............................. 7 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 CHAPTER ONE Taneyev’s contribution to Russian musical culture 1. Taneyev in the Moscow Conservatory: ……………………………….… 14 1.1. Founder of counterpoint class …………………………….…………. 15 2. Taneyev’s study of counterpoint: 2.1. Convertible Counterpoint in the Strict Style …………………….. 16 2.2. The Study of Canon ………………………………………………………… 18 3. Taneyev – pianist …………………………………………………………………. 19 CHAPTER TWO Interrelation of the fugue with other genres 1. Fugue as a model of generic counterpoint from Glinka to Taneyev …... 23 2. Fugue in Taneyev’s piano works: ……………………………………………………... 29 2.1. Fugue in D minor (unpublished) ……………….………………………..… 29 2.2. Prelude and Fugue in G sharp minor Op.29 ….……..………….……. 32 3. Implementation of the fugue in piano and chamber works of Taneyev, his students and successors: ………………………………………….………..…….… 41 3.1. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1990

Tanglewqpd 19 9 They dissolve the stresses and strains of everyday living. The Berkshires' most successful 4-seasons hideaway, a gated private enclave with 14 -mile lake frontage, golf and olympic pool, tennis, Fitness Center, lake lodge — all on the lake. Carefree 3 -and 4- Your bedroom country condominiums with luxury amenities and great skylights, fireplaces, decks. Minutes from Jiminy Peak, Brodie Berkshire Mountain, Tanglewood, Jacob's Pillow, Canyon Ranch. In the $200s. escape SEE FURNISHED MODELS, SALES CENTER TODAY. (413) 499-0900 or Tollfree (800) 937-0404 Dir: Rte. 7 to Lake Pontoosuc. Turn left at Lakecrest sign . „_ poxrrnosUC 7 ^^^^^ ON on Hancock Rd. /10 -mile to Ridge Ave. Right turn to Lakecrest gated entry. Offering by Prospectus only. Seiji Ozawa (TMC '60), Music Director Carl St. Clair (TMC '85) and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Ninth Season, 1989-90 •2"< Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Darling, Chairman Emeritus Nelson J. Jr., J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. I^ewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman Treasurer Mrs. John H . Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and David B.Arnold, Jr. Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Avram J . Goldberg Mrs. Robert B. Newman James K Cleary Mrs. John L. Grandin Peter C. Read John K Cogan.Jr. Francis W. Hatch, Jr. Richard A. Smith Julian Cohen Mrs. BelaT Kalman Ray Stata William M. Crazier, Jr. Mrs. George I. Kaplan William F. Thompson Mrs. Michael H. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T Zervas Trustees Emeriti Vernon R.