CEPAL Review No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoja Membretada

Informe Trimestral 4T15 Resultados y Hechos Relevantes del Cuarto Trimestre y Año Completo de 2015 Ventas Mismas Tiendas con crecimiento de 10.4% en el cuarto trimestre Incremento de 30.8% en el EBITDA del cuarto trimestre, logrando un margen de 15.3% Crecimiento de 74.3% en la Utilidad Neta del cuarto trimestre, alcanzando una utilidad por acción de 1.17 pesos 2,954 Unidades Totales en el portafolio, que incluye 170 unidades adicionales en comparación contra el año anterior MENSAJE DE LA DIRECCIÓN GENERAL Alberto Torrado, Presidente Ejecutivo de Alsea comentó: “Para Alsea, el 2015 fue un año positivo en donde continuamos consolidando nuestra presencia en los mercado donde operamos, mejorando el desempeño de nuestra operación y observando un entorno favorable en el consumo lo cual nos ayudó a mejorar el desempeño de la compañía, inclusive por encima de las expectativas que teníamos. Nuestro ADN innovador nos impulsa a seguir desarrollando distintos proyectos para estar a la vanguardia, no solo en términos tecnológicos, sino también en nuestra oferta de productos y servicios. Un claro ejemplo de lo anterior es el lanzamiento de las aplicaciones móviles de Domino’s Pizza y Burger King, al igual que nuestro programa de lealtad multi-marca “Wow Rewards” con el que estamos logrando un mayor acercamiento y comunicación a nuestros clientes, ofreciéndoles una forma sencilla para obtener beneficios inmediatos en nuestras tiendas.” Y agregó: “De cara al próximo año, continuaremos trabajando para seguir incrementando nuestra rentabilidad y enfocando todo nuestro esfuerzo en cumplir con el reto de mantener el ritmo de crecimiento para lograr las metas a 5 años que presentamos el pasado mes de noviembre durante nuestro primer día de Analistas e Inversionistas de Alsea.” Febrero, 2015 Informe Trimestral 4T15 México D.F. -

Disclaimer July 15, 2021 │ Update

Disclaimer July 15, 2021 │ Update The content here in has only informative purposes. It does not constitute a recommendation, advice, or personalized suggestion of any product and/or service that suggest you make investment decisions as it is necessary to previously verify the congruence between the client's profile and the profile of the financial product. SALES TRADING COMMENT, NOT RESEARCH OR HOUSE VIEW. The information contained in this electronic communication and any attached document is confidential, and is intended only for the use of the addressee. The information and material presented are provided for information purposes only. Please be advised that it is forbidden to disseminate, disclose or copy the information contained herein. If you received this communication by mistake, we urge you to immediately notify the person who sent it. Actinver and/or any of its subsidiaries do not guarantee that the integrity of this email or attachments has been maintained nor that it is free from interception, interference or viruses, so their reading, reception or transmission will be the responsibility of who does it. It is accepted by the user on the condition that errors or omissions shall not be made the basis for any claim, demand or cause for action. Equity Research Guide for recommendations on investment in the companies under coverage included or not, in the Mexican Stock Exchange main Price Index (S&P/BMV IPC) Our recommendations are set based on an expected projected return which, as any estimate, cannot be guaranteed. Readers should be aware that a number of subjective elements have also been taken into consideration in order to determine each analyst’s final decision on the recommendation. -

Boletín Laboral

BOLETÍN LABORAL CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, JUEVES 04 DE MARZO DEL 2021 TOMO NÚMERO COSTO 1 11213 $8.00 PESOS AVISO POR MEDIO DEL PRESENTE, SE DA A CONOCER A LITIGANTES Y PÚBLICO EN GENERAL, EL LISTADO DE ACUERDOS EMITIDOS POR JUNTA ESPECIAL A NOTIFICARSE EL DÍA 18 DE MARZO DE 2021, PARA EXPEDIENTES INGRESADOS HASTA EL 18 DE MARZO DEL 2020. SU INGRESO AL INMUEBLETENDRÁ LUGAR POR LA CALLE DE DR. ANDRADE, EN LA FECHA CITADA, LOS HORARIOS PARA LLEVAR ACABO ESTAS NOTIFICACIONES SERÁN PROPORCIONADOS POR CADA JUNTA ESPECIAL EN EL MOMENTO DE LA CONFIRMACIÓN DE SU CITA. PARA EXPEDIENTES INGRESADOS A PARTIR DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE DEL 2020, RECIBIRÁ EN EL CORREO ELECTRÓNICO REGISTRADO AL INGRESAR SU DEMANDA EN LA PLATAFORMA SIREDE, UN AVISO EN EL QUE SE LE JUEVES 04 DE MARZO DE 2021 http://www.juntalocal.cdmx.gob.mx PÁGINA 1 INDICARÁ EL DÍA Y HORA EN QUE DEBA PRESENTARSE A LA OFICIALÍA DE PARTES DE ESTE TRIBUNAL, A EFECTO DE HACER ENTREGA DEL ORIGINAL DEL ESCRITO INICIAL DE DEMANDA Y ANEXOS DIGITALIZADOS EN EL ARCHIVO PDF INGRESADO POR EL SISTEMA Y SUS RESPECTIVOS TRASLADOS. UNA VEZ COTEJADO EL ORIGINAL CON EL ARCHIVO PDF, SE PROCEDERÁ A LA NOTIFICACIÓN DE LA PARTE ACTORA DEL ACUERDO CORRESPONDIENTE EL CUAL SE HARÁ A PERSONA AUTORIZADA PARA ELLO EL INGRESO SERÁ POR LA CALLE DE DR. RÍO DE LA LOZA, EN UN HORARIO DE 10:00 A 15:00 HORAS. LAS PARTES COMPARECIENTES DEBERÁN ESTAR DEBIDAMENTE AUTORIZADAS PARA OÍR Y RECIBIR NOTIFICACIONES EN AUTOS Y TENDRÁN QUE PORTAR IDENTIFICACIÓN OFICIAL EN ORIGINAL. -

Panorama Bursátil. Voto De Confianza En Enero

15 de f ebrero de 2019 Octav io García Williams González Mesa de Análisis Ext. 10717 [email protected] Panorama Bursátil. Voto de confianza en enero Nuestra lectura del mercado ─ Optimismo en los mercados de EUA tras avances en las negociaciones comerciales con China. Las pláticas continuarán la próxima semana en Washington. En EUA el S&P 500 subió 2.3% y el DJIA 2.8%; mientras que México se ajustó 0.4% en pesos (-1.4% en dólares; el peso se depreció 0.9%). ¿Bolsa atractiva?…La renta fija dice que todavía no ─ Se comparó el rendimiento desde 2008 de las utilidades de la Bolsa en México (earnings yield o inverso del múltiplo P/U) contra el rendimiento o yield del Bono M a 10 años. El difícil entorno del mercado global en términos comerciales, las dudas en cuanto al crecimiento económico global, la política monetaria restrictiva la Fed, la incertidumbre interna, entre otros factores, hacen que rendimiento de las utilidades de la Bolsa en México no luzca su mejor versión, al ubicarse en 5.9% vs. ~8.5% del bono M a 10 años, aunque se reconoce que el diferencial entre ambos se ha recortado ~100pb en los últimos cinco meses. Flujos de extranjeros a la renta variable nacional ─ Tras el fuerte ajuste del mercado en 2018 (-15.6%), y apoyados por una menor aversión al riesgo en mercados emergentes, los extranjeros dieron el voto de confianza al mercado local al traer flujos por más de US$500 millones en enero que ayudaron al índice a subir 5.6% en el primer mes del año. -

MEXICO Executive Summary

Underwritten by CASH AND TREASURY MANAGEMENT COUNTRY REPORT MEXICO Executive Summary Banking Mexico’s central bank, Banco de México (Banxico), is an independent body under the country’s constitution. It is responsible for monetary policy and is lender of last resort and provider of treasury services to the federal government. Banco de México shares responsibility for exchange rate policy and regulatory supervision of the finance sector with the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público). Mexico does not apply central bank reporting requirements or export controls. Resident entities are permitted to retain both MXN (Mexican peso) and foreign currency bank accounts domestically and abroad. Non-resident entities may hold domestic and foreign currency bank accounts within Mexico. Local currency accounts are not convertible into foreign currency. Mexico’s stable and well capitalized banking system is dominated by large foreign-owned institutions following a period of privatization and consolidation in the early 2000s sparked by legislation permitting foreign investment in the sector. Banks currently operating in Mexico include 23 financial groups, 50 multiple banks, six development banks, 84 credit unions and 39 representative offices of foreign banks. Payments Mexico’s high- and low-value clearing systems (SPEI and SICAM) are owned and operated by the central bank. CECOBAN, a consortium of banks, owns and operates CCEN, a clearing system for retail payments. Electronic credit transfers are widely used by large companies, while debit and credit cards are very popular for retail payments. Cash and checks are still commonly used by smaller firms and households. Internet-based electronic banking services are offered to both corporate and retail customers. -

Solid Profitable Growth

SOLID PROFITABLE GROWTH 2015 Annual report For more than 20 years, we have been supporting our clients with top quality financial services. We are a company with a reputation for building solid, lasting alliances with our clients. We want to become the leading company in our market by helping companies to grow thus making Mexico stronger. 2 SOLID PROFITABLE GROWTH With a multi-product offering focused on three core business lines —leasing, factoring and auto loans— UNIFIN’s financial solidity comes from its origination process and its skillful, well-timed portfolio management. Total portfolio Ps. 18.9 billion 3 SOLID • The compiled information is submitted to a The loan origination process is handled by a special- credit committee: i) Minor Risk Committee for ized team in each business line, using cutting-edge transactions below Ps. 7.5 million, with a dig- technology and various selection criteria: ital response within 72 hours; ii) Major Risk Loan origination process Committee, which meets in person to decide • Strict and formal analysis of national and ION on larger transactions, providing a response VAT CL ENO IEN global economies and trends in various R T P ND R within two weeks. A OS LE P industries. A EC S TI ET N S G S • We also have highly rigorous systems involv- A 6 • 16 dynamic credit scorings, analysis for ma- 1 ing month to month tracking and monitoring, jor and minor risk and analytic parameters that in compliance with anti-money laundering are part of our in-house model. and data privacy laws. 5 E E T A T P I P M L I M C O A C 2 T I T O I N D E R Collection process C 4 -5 0 2-7 8-30 31-60 61-90 +90 C R E D I S T E B C U N E 3 R R E E A F U E R A N D Administrative L E E-mail G A In-person L Payment Call center Workout Court collection reminder collection date 2nd reminder collection TEAM 1 TEAM 2 TEAM 3 TEAM 4 Collection is simpler because UNIFIN maintains ownership of the assets. -

Corporate Presentation May 2021 the Only Specialty Retail REIT in México

Credit Suisse: Mexico Investment Ideas 2021 Corporate Presentation May 2021 The only specialty retail REIT in México We own GLA of 543,432 sqm and manage in total 619,379 sqm, including the co-investments in projects the total managed is 767,237 thousand sqm. 19 shopping centers: 8FashionMalls 7PowerCenters 4 Community Centers Solid operational structure and corporate governance that guarantee transparency, efficiency and a sustainable and profitable growth model. FibraShop Managed Co-in vestments Portfolio location Community Center Properties Location UC Jurica Querétaro UC Juriquilla Querétaro UC Xalapa Xalapa UC Nima Shops Puerto Vallarta Power Center Properties Location Puerta Texcoco Texcoco Los Atrios Cuautla Galerías Tapachula Tapachula City Center Esmeralda State of Mexico Plaza Cedros Cuernavaca Cruz del Sur Puebla Sentura State of Mexico Fashion Mall Properties Location Plaza Cibeles Irapuato La Luciérnaga San Miguel de Allende Puerto Paraíso Cabo San Lucas Kukulcán Plaza Cancún Galerías Mall Sonora Hermosillo Las Misiones Juárez Puerta La Victoria Querérato La Perla * Guadalajara We are in 12 states of the Mexican Republic Total portfolio weighted average occupancy rate: 92.13%* Shopping center 1Q 2020 2Q 2020 3Q 2020 4Q 2020 1Q 2021 Plaza Cibeles 100 98 98 97 97 La Luciérnaga 100 100 99 98 97 Puerto Paraíso 9493928989 Kukulcán Plaza* 85 83 82 79 79 UC Jurica 92 90 89 84 84 UC Juriquilla 91 90 90 87 87 UC Xalapa 88 87 87 85 84 Puerta Texcoco 9896959493 UC Nima Shops 96 92 90 87 87 Plaza Los Atrios 99 99 99 99 100 Galerías Tapachula -

ALSEA Greater Than Expected Impact of the Pandemic @Analisis Fundam

Equity Research M exico ALSEA Quarterly Report May 4, 2021 www.banorte.com Greater than expected impact of the pandemic @analisis_fundam ▪ Alsea's report was weak, with the impact of the sanitary measures Consumer and Telecom being greater than expected. However, the recovery observed in March points to a more favorable outlook going forward Valentín Mendoza Senior Strategist, Equity [email protected] ▪ We believe the hardest times are behind us. The economic recovery and the progress in vaccine distribution should support the recovery, Juan Barbier, CFA Analyst which should be reflected in significant growth [email protected] ▪ We set a PT of MXN 39.00 (FV/EBITDA 2021E of 7.8x below current HOLD multiple). However, given a limited return after the recent rally, we Current Price $34.18 downgrade our rating to HOLD PT $39.00 Upside Potential 14.1% Max – Min LTM ($) 36.7 – 17.6 The pandemic impacted profitability in Europe more than expected. In the Market Cap (US$m) 1,429.4 face of the reinforced sanitary measures in all regions, implementing temporary Shares Outstanding (m) 838.6 Float 48.52% (and some permanent) unit closures, as well as time and capacity restrictions, Daily Turnover US$m 70.4 figures for the quarter were below our estimates. Revenues declined 15.6% y/y Valuation metrics LTM FV/EBITDA 13.0x to MXN 10.212 billion, as a result of a 13.3% y/y decline in consolidated SSS P/E N.A. (Mexico: -8.4%; Europe: -29.2%; South America: +4.9%), reflecting the effects MSCI ESG Rating* N.A. -

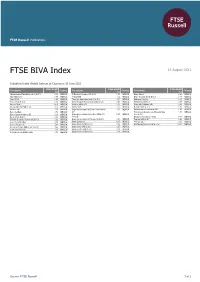

FTSE BIVA Index

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE BIVA Index Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) Administradora Fibra Danhos S.A. de C.V. 0.15 MEXICO El Puerto de Liverpool SA de CV 0.53 MEXICO Grupo Mexico 8.89 MEXICO Alfa SAB de CV 0.89 MEXICO Femsa UBD 9.2 MEXICO Grupo Rotoplas S.A.B. de C.V. 0.17 MEXICO Alpek S.A.B. 0.28 MEXICO Fibra Uno Administracion S.A. de C.V. 1.91 MEXICO Industrias Penoles 1.02 MEXICO Alsea S.A.B. de C.V. 0.56 MEXICO Genomma Lab Internacional S.A.B. de C.V. 0.46 MEXICO Kimberly Clark Mex A 0.88 MEXICO America Movil L 13.59 MEXICO Gentera SAB de CV 0.35 MEXICO Megacable Holdings SAB 0.64 MEXICO Arca Continental SAB de CV 1.53 MEXICO Gruma SA B 1.37 MEXICO Nemak S.A.B. de C.V. 0.16 MEXICO Bachoco Ubl 0.36 MEXICO Grupo Aeroportuario del Centro Norte Sab de 1.31 MEXICO Orbia Advance Corporation SAB 1.59 MEXICO Banco del Bajio 0.76 MEXICO CV Promotora y Operadora de Infraestructura 1.05 MEXICO Banco Santander Mexico (B) 0.43 MEXICO Grupo Aeroportuario del Pacifico SAB de CV 2.27 MEXICO S.A. de C.V. Becle S.A.B. de C.V. 0.86 MEXICO Series B Qualitas Controladora y Vesta 0.48 MEXICO Bolsa Mexicana de Valores SAB de CV 0.62 MEXICO Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste SA de CV 2.21 MEXICO Regional SAB de CV 0.83 MEXICO Cementos Chihuahua 0.79 MEXICO Grupo Banorte O 11.15 MEXICO Televisa 'Cpo' 4.38 MEXICO Cemex Sa Cpo Line 7.43 MEXICO Grupo Bimbo S.A.B. -

Striving to Overcome the Economic Crisis: Progress and Diversification of Mexican Multinationals’ Export of Capital

Striving to overcome the economic crisis: Progress and diversification of Mexican multinationals’ export of capital Report dated December 28, 2011 EMBARGO: The contents of this report cannot be quoted or summarized in any print or electronic media before December 28, 2011, 7:00 a.m. Mexico City; 8:00 a.m. NewYork; and 1 p.m. GMT. Mexico City and New York, December 28, 2011: The Institute for Economic Research (IIEc) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment (VCC), a joint initiative of the Columbia Law School and the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York, are releasing the results of their third survey of Mexican multinationals today. 1 The survey is part of a long-term study of the rapid global expansion of multinational enterprises 2 (MNEs) from emerging markets. The present report focuses on data for the year 2010. Highlights In 2010, the top 20 Mexican MNEs had foreign assets of USDD 123 billion (table 1 below), foreign sales of USDD 71 billion, and employed 255,340 people abroad (see annex table 1 in annex I). The top two firms, America Movil and CEMEX, together controlled USDD 85 billion in foreign assets, accounting for nearly 70% of the assets on the list. The top four firms (including FEMSA and Grupo Mexico) jointly held USDD 104 billion, which represents almost 85% of the list’s foreign assets. Leading industries in this ranking, by numbers of MNEs, are non-metallic minerals (four companies) and food and beverages (another four companies). -

CORPORACION GEO, SAB De CV

PROSPECTO DEFINITIVO. Los valores mencionados en el Prospecto Definitivo han sido registrados en el Registro Nacional de Valores que lleva la CNBV, los cuales no podrán ser ofrecidos ni vendidos fuera de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, a menos que sea permitido por las leyes de otros países. DEFINITIVE PROSPECTUS. These securities have been registered with the securities section of the National Registry of Securities (RNV) maintained by the CNBV. They can not be offered or sold outside the United Mexican States unless it is permitted by the laws of other countries. CORPORACIÓN GEO, S.A.B. DE C.V. EMISIÓN ÚNICA DE 7’000,000 (SIETE MILLONES) DE CERTIFICADOS BURSÁTILES MONTO TOTAL DE LA OFERTA PÚBLICA $700,000,000.00 (SETECIENTOS MILLONES DE PESOS 00/100 M.N.) Emisor: Corporación Geo, S.A.B. de C.V. Tipo de Valor: Certificados Bursátiles. Clave de Pizarra: GEO 06. Denominación de la Moneda de Referencia: En pesos. Valor Nominal de los Certificados: $100.00 (CIEN PESOS 00/100 M.N.). Precio de Colocación: $100.00 (CIEN PESOS 00/100 M.N.). No. de Títulos: 7'000,000 (SIETE MILLONES) de Certificados Bursátiles. Plazo de la Emisión: 1,848 días, equivalentes a 22 períodos de 84 días (aproximadamente 5 años). Recursos Netos que Obtendrá el Emisor: Aproximadamente $693,759,073. (SEISCIENTOS NOVENTA Y TRES MILLONES SEISCIENTOS CINCUENTA Y NUEVE MIL SETENTA Y TRES PESOS 78/100 M.N.). Garantía: Avales de las subsidiarias de Corporación Geo, S.A.B. de C.V. que a continuación se mencionan: Geo Edificaciones, S.A. de C.V., Geo Hogares Ideales, S.A. -

México, D.F. Noviembre 2012

INSTITUTO POLITÉCNICO NACIONAL ESCUELA SUPERIOR DE COMERCIO Y ADMINISTRACIÓN UNIDAD TEPEPAN SEMINARIO: ANÁLISIS DE INVERSIONES TEMA: FORMACIÓN DE PORTAFOLIOS ÓPTIMOS CON LAS ACCIONES: GEO B, GFINBUR O, GRUMA B, LIVEPOL C-1 Y PEÑOLES* INFORME FINAL QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE CONTADOR PÚBLICO PRESENTAN: ALAN YAEL AGUILAR VILLARON ALEJANDRA MAYTE VALENCIA MARTINEZ BRENDA MANRIQUE RAMÍREZ MARIANA MIRIEL AGUILAR RODOLFO GALEANA VALENCIA CONDUCTORES DEL SEMINARIO: M. EN F. RAFAEL GUADALUPE RODRÍGUEZ CALVO M. EN C. AIDÉ NIDIA REYES LOYOLA M. EN C. RAÚL GARRIDO VILLEGAS MÉXICO, D.F. NOVIEMBRE 2012 AGRADECIMIENTOS El Instituto Politécnico Nacional, por abrirnos sus puertas para seguir con este sueño y permitirnos pertenecer a tan distinguida institución, por su excelente calidad educativa y quien fue testigo y parte de innumerables escenarios durante nuestra estancia en el mismo, los cuales serán inolvidables. A la Escuela Superior de Comercio y Administración, Unidad Tepepan, Quien nos vio llegar como estudiantes con grandes ilusiones, en donde nos formamos profesionalmente y que hoy nos despide como Contadores Públicos. A nuestros profesores quienes son parte de este y muchos de nuestros logros, por ser parte de nuestra familia, los cuales nos apoyaron, regañaron y trabajaron junto a nosotros, porque sembraron una semilla y en este largo trayecto ahora llegan a cosechar sus frutos. Por enseñarnos lo que sabemos, por guiarnos para llegar a este momento de nuestras vidas, porque este logro es de ustedes también. 2 ÍNDICE ÍNDICE DE TABLAS ÍNDICE DE GRÁFICAS ABREVIATURAS INTRODUCCIÓN CAPÍTULO 1. MARCO TEÓRICO: TEORÍA MODERNA DE LA CARTERA 1.1. Inversiones en valores 3 1.2.