Nber Working Paper Series the Cross Border Mergers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Banking Announcement

Frequently asked questions 26 May 2021 What the repositioning of the HSBC USA Wealth and Personal Banking business means for our customers, here and abroad Why did HSBC take this action? In February 2020, we set out a plan to shift our business strategy in the United States to maximize the connection between our clients and our world-class international network. Our primary business will be a wholesale bank focused on the international needs of clients. We are renewing our emphasis on the US$5 trillion international wealth management opportunity from globally mobile and affluent individuals in the United States. Is HSBC exiting the United States? No, HSBC is not exiting its US business. We aim to be the leading international bank in the United States and are focused on what we do best – connecting Americans to a world of opportunity and bringing cross-border business and investment to the United States. We will continue to provide banking services not only to our wholesale banking clients, but also to our Premier, Jade and Private Banking customers. I have personal accounts at HSBC and I’m in the United States. How will these agreements affect me? Upon completion of the transactions, the accounts of in-scope customers will be transferred to Citizens or Cathay Bank. We thank those customers for their business and will ensure the transfer occurs with as minimum disruption as possible. Premier, Jade, Private Banking and other clients who will remain HSBC customers are in the process of being transitioned to one of our new 20-25 Wealth Centers. -

Citizens Financial Group, Inc

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Summary December 31, 2016 CFG 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Section PUBLIC SECTION Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Material Entities............................................................................................................... 3 2. Core Business Lines ....................................................................................................... 3 3. Summary of Financial Information, Capital and Major Funding Sources........................ 7 4. Derivative and Hedging Activities.................................................................................... 10 5. Membership in Material Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems ............................ 12 6. Foreign Operations ......................................................................................................... 13 7. Material Supervisory Authorities...................................................................................... 13 8. Principal Officers ............................................................................................................. 14 9. Resolution Planning Corporate Governance, Structure and Processes ......................... 14 10. Material Management Information Systems.................................................................. 14 11. High Level Description of Citizens' Resolution Strategy............................................... -

Transformation Solutions, Unlocking Value for Clients

CEO Study Telecom Implementations Chris Pearson Global Business Consulting Industry Leader 21.11.2008 1 IBM Telecom Industry Agenda . CEO Study – Enterprise of the Future . IBM’s view of the Telecom market . IP Economy . The Change agenda . World is becoming Smarter 2 Storm Warning | ZA Lozinski | Clouds v0.0 - September 2008 | IBM Confidential © 2008 IBM Corporation We spoke toIBM 1,130 Telecom CEOs Industry and conducted in-depth analyses to identify the characteristics of the Enterprise of the Future How are organizations addressing . New and changing customers – changes at the end of the value chain . Global integration – changes within the value chain . Business model innovation – their response to these changes Scope and Approach: 1,130 CEOs and Public Sector Leaders . One-hour interviews using a structured questionnaire . 78% Private and 22% Public Sector . Representative sample across 32 industries . 33% Asia, 36% EMEA, 31% Americas . 80% Established and 20% Emerging Economies Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative . Respondents’ current behavior, investment patterns and future intent . Choices made by financial outperformers . Multivariate analysis to identify clusters of responses . Selective case studies of companies that excel in specific areas 3 Storm Warning | ZA Lozinski | Clouds v0.0 - September 2008 | IBM Confidential © 2008 IBM Corporation IBM Telecom Industry The Enterprise of the Future is . 1 2 3 4 5 Hungry Innovative Globally Disruptive Genuine, for beyond integrated by not just change customer nature generous imagination 4 Storm Warning | ZA Lozinski | Clouds v0.0 - September 2008 | IBM Confidential © 2008 IBM Corporation Telecom CEOsIBM Telecom anticipate Industry more change ahead; are adjusting business models; investing in innovation and new capabilities Telecom CEOs : Hungry . -

MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT USA/Canada Region

MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT USA/Canada Region 2019 SIXTY-SECOND AND ONE HUNDRED–TWELFTH ANNUAL ASSEMBLY JOURNAL SESSION HELD AT ELLICOTT CITY, MARYLAND APRIL 6 – 7, 2019 Our Shared Mission To advance the ministry of Jesus Christ. Our Shared Vision Compelled by God we ARE a movement of people who passionately live the story of Jesus Christ Our Core Values Spiritual Formation Leadership Development Congregational Vitality Missional Expansion Stewardship Advancement Our Principles for Ministry Re-thinking Mental Models to develop versatile and adaptable congregations Reproducing and Multiplying disciples, pastors and leaders Partnering and Collaborating with churches and groups outside the local congregation to experience the movement of God Moving with God now Sixty-Second & One Hundred-Twelfth Annual Assembly Journal of the Mid-Atlantic District Church of the Nazarene Session held at Ellicott City, Maryland April 6 - 7, 2019 Dr. David A. Busic Dr. David W. Bowser General Superintendent District Superintendent SESSIONS OF THE WASHINGTON / MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT ASSEMBLY The original Washington District was organized in 1907 following the union of the eastern and western branches of the Holiness movements into the Pentecostal Church of the Nazarene in Chicago, IL. The First District Assembly of the original Washington District was held on April 30, 1908, at Harrington, Del, with Dr. P.F. Breese as the presiding general superintendent; Rev. H. B. Hosley as district superintendent; and Rev. Bessie Larkin as district secretary. At that time there were only five churches: Bowens, MD; Harrington, DE; Hollywood, MD; Washington, DC 2nd Church; and the largest, John Wesley Church in Washington, DC. The new district had a total membership of 418. -

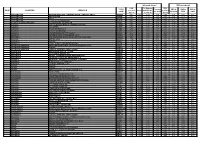

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

Telecom Operators

March 2007 Telecom Operators Caution – work ahead Accelerating decline in voice to be offset by siginificant take-off in data? Reorganization of the value chain: necessary but not without risk Critical size and agility: has anyony got both? - Renewed ambitions of leaders and intensified pressure on challengers: M&A activity to gather pace Contacts EXANE BNP Paribas Antoine Pradayrol [email protected] Exane BNP Paribas, London: +44 20 7039 9489 ARTHUR D. LITTLE Jean-Luc Cyrot [email protected] Arthur D. Little, Paris: +33 1 55 74 29 11 Executive summary Strategic reorientation: unavoidable, and beneficial in the near term... More than ever, European telecom operators must juggle between shrinking revenues in their traditional businesses on the one hand, and opportunities to capture growth in attractive new markets on the other, driven by the development of fixed and mobile broadband. Against this background, carriers will step up initiatives to cut costs and secure growth. They are gradually acknowledging that they cannot be present at every link in the value chain, and that even on those links that constitute their core business, they can create more value by joining forces with partners. This should result in a variety of ‘innovations’, such as: – outsourcing of passive and even active infrastructures and/or network sharing in both fixed line and mobile; – development of wholesale businesses and virtual operators (MVNOs, MVNEs, FVNOs, CVNOs1, etc.); – partnerships with media groups and increasingly with Internet leaders. These movements will: – enable companies to trim costs and capex: all else being equal, the outsourcing of passive or active infrastructures and network sharing can increase carriers’ operating free cash flow by up to 10%; – stimulate market growth: partnerships with media groups and Internet leaders have demonstrated that they can stimulate usage without incurring a significant risk of cannibalisation in the near term. -

Annual Report & Accounts 1998

Annual report and accounts 1998 Chairman’s statement The 1998 financial year proved to be a very Turnover has grown by 4.7 per cent and we important chapter in the BT story, even if not have seen strong growth in demand. Customers quite in the way we anticipated 12 months ago. have benefited from sound quality of service, price cuts worth over £750 million in the year, This time last year, we expected that there was a and a range of new and exciting services. Our good chance that our prospective merger with MCI Internet-related business is growing fast and we Communications Corporation would be completed are seeing considerable demand for second lines by the end of the calendar year. In the event, of and ISDN connections. We have also announced course, this did not happen. WorldCom tabled a a major upgrade to our broadband network to considerably higher bid for MCI and we did not match the ever-increasing volumes of data we feel that it would be in shareholders’ best interests are required to carry. to match it. Earnings per share were 26.7 pence and I am In our view, the preferable course was to pleased to report a final dividend for the year of accept the offer WorldCom made for our 20 per 11.45 pence per share, which brings the total cent holding in MCI. On completion of the dividend for the year to 19 pence per share, MCI/WorldCom merger, BT will receive around which is as forecast. This represents an increase US$7 billion (more than £4 billion). -

Natwest Group United Kingdom

NatWest Group United Kingdom Active This profile is actively maintained Send feedback on this profile Created before Nov 2016 Last update: Feb 23 2021 About NatWest Group NatWest Group, founded in 1727, is a British banking and insurance holding company based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Its main subsidiary companies are The Royal Bank of Scotland, NatWest, Ulster Bank and Coutts. Prior to a name-change in July 2020, it was known as Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Group. After a massive bailout in 2008, a majority of RBS' shares were purchased by the UK Government. In 2014 the bank embarked on a restructuring process that saw it refocus on its business in the UK and Ireland. As part of this process it divested its ownership of Citizens Financial Group, the 13th largest bank in the United States, in 2015. As of 2020 it remains 61.93% UK Government owned, via UK Financial Investments (UKFI). Website https://www.natwestgroup.com/ Headquarters 36 St Andrew Square EH2 2YB Edinburgh Scotland United Kingdom CEO/chair Alison Rose CEO Supervisor Bank of England Annual report Annual report 2020 Ownership listed on London Stock Exchange Natwest Group is majority-owned by the UK government since 2008, which currently holds 61.93 % of the shares. Complaints NatWest Group does not operate a complaints channel for individuals and communities that may be adversely affected by and its finance. However, the bank can be contacted via the contact form here (e.g. using ‘General Service’ as account type). grievances Stakeholders may raise complaints via the OECD National Contact Points (see OECD Watch guidance). -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

KPN Q2 2019 Press Release

Press release 24 July 2019 Second quarter 2019 results Operational highlights • Solid performance in Consumer convergence, partially due to Telfort integration − +41k fixed-mobile households (of which +38k Telfort), 48% of broadband base (Q2 2018: 44%) − +104k fixed-mobile postpaid customers (of which +54k Telfort), 62% of postpaid base (Q2 2018: 54%) • Single-play services impacted by Telfort integration and ongoing competition − Fixed: -24k1 broadband and -7k IPTV net adds; ARPU increased 6.0% y-on-y to € 46 − Mobile: +17k KPN brand postpaid net adds, flat postpaid customer base across all brands; postpaid ARPU of € 17, flat q-on-q and 5.6% lower y-on-y − Consumer NPS +13 (Q2 2018: +13) • Good progress with customer migrations in Business, negatively impacting revenues in short term − 59% of SME customers migrated from traditional fixed voice or legacy broadband services − Business NPS of +1 (Q2 2018: -4) • Net indirect opex savings2 of € 40m in Q2 2019, € 66m in H1 2019 • Progress in simplification of the company − Disposal of NLDC and international network announced − Sale of TEFD stake completed Key figures* Group financials (unaudited) Q2 2018 Q2 2019 Δ y-on-y H1 2018 H1 2019 Δ y-on-y (in € m, unless stated otherwise) Adjusted revenues** 1,402 1,359 -3.1% 2,804 2,721 -3.0% EBITDA 596 602 1.1% 1,194 1,172 -1.8% Adjusted EBITDA after leases** 573 594 3.6% 1,138 1,157 1.7% As % of Adjusted revenues 40.9% 43.7% 40.6% 42.5% Operating profit (EBIT) 218 221 1.6% 433 410 -5.3% Net profit 142 128 -9.8% 245 217 -11% Capex 245 269 9.9% 481 531 10% Free cash flow (excl. -

Dr. Neuhaus Telekommunikation Mobile Network Code

Dr. Neuhaus Telekommunikation Mobile Network Code The Mobile Country Code (MCC) is the fixed country identification. The Mobile Network Code (MNC) defines a GSM‐, UMTS‐, or Tetra radio network provider. This numbers will be allocates June 2011 autonomus from each country. Only in the alliance of bothscodes (MCC + MNC) the mobile radio network can be identified. All informations without guarantee Country MCC MNC Provider Operator APN User Name Password Abkhazia (Georgia) 289 67 Aquafon Aquafon Abkhazia (Georgia) 289 88 A-Mobile A-Mobile Afghanistan 412 01 AWCC Afghan Afghanistan 412 20 Roshan Telecom Afghanistan 412 40 Areeba MTN Afghanistan 412 50 Etisalat Etisalat Albania 276 01 AMC Albanian Albania 276 02 Vodafone Vodafone Twa guest guest Albania 276 03 Eagle Mobile Albania 276 04 Plus Communication Algeria 603 01 Mobilis ATM Algeria 603 02 Djezzy Orascom Algeria 603 03 Nedjma Wataniya Andorra 213 03 Mobiland Servei Angola 631 02 UNITEL UNITEL Anguilla (United Kingdom) 365 10 Weblinks Limited Anguilla (United Kingdom) 365 840 Cable & Antigua and Barbuda 344 30 APUA Antigua Antigua and Barbuda 344 920 Lime Cable Antigua and Barbuda 338 50 Digicel Antigua Argentina 722 10 Movistar Telefonica internet.gprs.unifon.com. wap wap ar internet.unifon Dr. Neuhaus Telekommunikation Mobile Network Code The Mobile Country Code (MCC) is the fixed country identification. The Mobile Network Code (MNC) defines a GSM‐, UMTS‐, or Tetra radio network provider. This numbers will be allocates June 2011 autonomus from each country. Only in the alliance of bothscodes (MCC + MNC) the mobile radio network can be identified. All informations without guarantee Country MCC MNC Provider Operator APN User Name Password Argentina 722 70 Movistar Telefonica internet.gprs.unifon.com. -

Home Field Advantage It Has Proven Difficult for Global Banks to Run a Successful Retail Banking Business Outside Their Core Domestic Markets

Sector: Banks Kathleen Shanley, CFA June 2, 2021 [email protected] Home Field Advantage It has proven difficult for global banks to run a successful retail banking business outside their core domestic markets. Citigroup, which had been the most ambitious U.S. bank operating overseas, said in April that it would retreat from consumer banking in 13 primarily Asian countries including China, Indonesia, and Korea, as well as Australia, Poland, and Russia (see GC report dated 4/19/21). Foreign banks operating in the U.S. have fared no better, opening an opportunity for U.S.-based banks to extend their domestic franchises. Just yesterday, PNC Financial Services completed its $11.6 billion acquisition of BBVA USA Bancshares from its Spanish parent company Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, S.A. (see GC report dated 4/27/21). Citizens Financial Group (CFG) is the latest regional bank to capitalize on this trend. Last week, the company said it will acquire 80 branches and an online deposit business, including $9.0 billion in deposits and $2.2 billion in loans, from HSBC Bank U.S.A. HSBC is giving up on mass market retail banking in the U.S., ending relationships with retail clients maintaining balances below $75,000 and small businesses with less than $5 million in annual revenue. (It will continue to do wholesale business in the U.S.) The company had already signaled last year that it would shift its investments away from underperforming areas in the U.S. and Europe, to focus on higher growth markets, primarily in Asia.