Aitken 1923 R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Evolution of Human Fire Use

ON THE EVOLUTION OF HUMAN FIRE USE by Christopher Hugh Parker A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology The University of Utah May 2015 Copyright © Christopher Hugh Parker 2015 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Christopher Hugh Parker has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Kristen Hawkes , Chair 04/22/2014 Date Approved James F. O’Connell , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Henry Harpending , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Andrea Brunelle , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Rebecca Bliege Bird , Member Date Approved and by Leslie A. Knapp , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Anthropology and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Humans are unique in their capacity to create, control, and maintain fire. The evolutionary importance of this behavioral characteristic is widely recognized, but the steps by which members of our genus came to use fire and the timing of this behavioral adaptation remain largely unknown. These issues are, in part, addressed in the following pages, which are organized as three separate but interrelated papers. The first paper, entitled “Beyond Firestick Farming: The Effects of Aboriginal Burning on Economically Important Plant Foods in Australia’s Western Desert,” examines the effect of landscape burning techniques employed by Martu Aboriginal Australians on traditionally important plant foods in the arid Western Desert ecosystem. The questions of how and why the relationship between landscape burning and plant food exploitation evolved are also addressed and contextualized within prehistoric demographic changes indicated by regional archaeological data. -

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1967 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Advisory Editors: M. A. Baumhoff, D. J. Crowley, C. J. Erasmus, T. D. McCown, C. W. Meighan, H. P. Phillips, M. G. Smith Volume 25 Approved for publication May 20, 1966 Issued May 29, 1967 Price, $1.50 University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles C alifornia Cambridge University Press London, England Manufactured in the United States of America CONTENTS Introduction ............................................ 1 The Southwestern Pomo in Russian Times: An Account by Kostromitonow ..1 Data Obtained from Herman James ..5 Neighboring Indian Groups .. 5 Informants ..5 Orthography ..6 Habitat .. 7 Village Sites ..7 Ethnobotany ..10 Ethnozoology. .16 Mammals .16 Birds. 17 Reptiles and batrachians .19 Fishes . 19 Insects and other terrestrial invertebrates. 20 Marine invertebrates .20 Culture Element List .21 Notes on culture element list .38 Appendix: Comparative Notes on Two Historic Village Sites by Clement W. Meighan. 46 Works Cited .............................................. 48 [ v ] ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD INTRODUCTION* The Southwestern Pomo were among the most primitive Charles Haupt married a woman from Chibadono of the California aborigines, a fact to be correlated with [ci'?bad6no] (near Plantation and on the same ridge). She their mountainous terrain on a rugged, inhospitable coast. was called Pashikokoya [pasilk6?koya? ], "cocoon woman" Their low culture may be contrasted with the richer cul- (pashikoyoyu [pa'si-oyo-yu], cocoon used on shaman' s ture of the Pomo of the Russian River Valley and Clear rattle; ya?, personal suffix), but her English name was Lake, environments which offered opportunities for Molly. -

Low-Impact Living Initiative

firecraft what is it? It's starting and managing fire, which requires fuel, oxygen and ignition. The more natural methods usually progress from a spark to an ember to a flame in fine, dry material (tinder), to small, thin pieces of wood (kindling) and then to firewood. Early humans collected embers from forest fires, lightning strikes and even volcanic activity. Archaeological evidence puts the first use of fire between 200-400,000 years ago – a time that corresponds to a change in human physique consistent with food being cooked - e.g. smaller stomachs and jaws. The first evidence of people starting fires is from around 10,000 years ago. Here are some ways to start a fire. Friction: rubbing things together to create friction Sitting around a fire has been a relaxing, that generates heat and produces embers. An comforting and community-building activity for example is a bow-drill, but any kind of friction will many millennia. work – e.g. a fire-plough, involving a hardwood stick moving in a groove in a piece of softwood. what are the benefits? Percussion: striking things together to make From an environmental perspective, the more sparks – e.g. flint and steel. The sharpness of the natural the method the better. For example, flint creates sparks - tiny shards of hot steel. strikers, fire pistons or lenses don’t need fossil Compression: fire pistons are little cylinders fuels or phosphorus, which require the highly- containing a small amount of tinder, with a piston destructive oil and chemical industries, and that is pushed hard into the cylinder to compress friction methods don’t require the mining, factories the air in it, which raises pressure and and roads required to manufacture anything at all. -

Fire Before Matches

Fire before matches by David Mead 2020 Sulang Language Data and Working Papers: Topics in Lexicography, no. 34 Sulawesi Language Alliance http://sulang.org/ SulangLexTopics034-v2 LANGUAGES Language of materials : English ABSTRACT In this paper I describe seven methods for making fire employed in Indonesia prior to the introduction of friction matches and lighters. Additional sections address materials used for tinder, the hearth and its construction, some types of torches and lamps that predate the introduction of electricity, and myths about fire making. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction; 2 Traditional fire-making methods; 2.1 Flint and steel strike- a-light; 2.2 Bamboo strike-a-light; 2.3 Fire drill; 2.4 Fire saw; 2.5 Fire thong; 2.6 Fire plow; 2.7 Fire piston; 2.8 Transporting fire; 3 Tinder; 4 The hearth; 5 Torches and lamps; 5.1 Palm frond torch; 5.2 Resin torch; 5.3 Candlenut torch; 5.4 Bamboo torch; 5.5 Open-saucer oil lamp; 5.6 Footed bronze oil lamp; 5.7 Multi-spout bronze oil lamp; 5.8 Hurricane lantern; 5.9 Pressurized kerosene lamp; 5.10 Simple kerosene lamp; 5.11 Candle; 5.12 Miscellaneous devices; 6 Legends about fire making; 7 Additional areas for investigation; Appendix: Fire making in Central Sulawesi; References. VERSION HISTORY Version 2 [13 June 2020] Minor edits; ‘candle’ elevated to separate subsection. Version 1 [12 May 2019] © 2019–2020 by David Mead All Rights Reserved Fire before matches by David Mead Down to the time of our grandfathers, and in some country homes of our fathers, lights were started with these crude elements—flint, steel, tinder—and transferred by the sulphur splint; for fifty years ago matches were neither cheap nor common. -

AL Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source

Masks and Moieties as a Culture Complex. Author(s): A. L. Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 50 (Jul. - Dec., 1920), pp. 452-460 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843493 Accessed: 01-02-2016 04:49 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 204.235.148.92 on Mon, 01 Feb 2016 04:49:06 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 452 MASKS AND MOIETIES AS A CULTURE COMPLEX. By A. L. KROEBERAND CATHARINEHOLT. IN 1905, Graebnerand Ankermannpublished synchronous articlesL in which they distinguisheda nlumberof successivelayers of culturein Oceania and Africa. This scheme Graebnersubsequently developed in an essay which traced at least some of these culturestrata as far as America.2 Graebner'stheory has been accepted, with or without reservations,by a number of authorities,including Foy,3 W. -

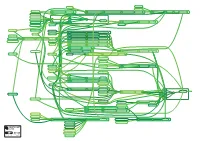

A1128 Able to Light a Fire Map of Influence

11591: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A LIMPET SHELL 12278: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A SAW 12113: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A MUSSEL SHELL 09112: A HUMAN BEING CUSTOMER 09475: A HUMAN BEING IN 12729: A HUMAN BEING IN 12281: A HUMAN BEING IN OF WH SMITH OR OR AND OR OR POSSESSION OF A ELASTIC BAND POSSESSION OF A WOOD WASHER AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE BOW DRILL FIRE LIGHTER 10630: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CHERRY TREE OUTER BARK 12394: A HUMAN BEING IN OR POSSESSION OF A RIBWORT PLANTAIN PLANT LEAF 11946: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND OR POSSESSION OF STINGING NETTLE PLANT BARK 09477: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CORDAGE 11550: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR 10437: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND POSSESSION OF A BOW POSSESSION OF WHITE WILLOW TREE INNER BARK 13740: A HUMAN BEING IN 00924: A HUMAN BEING USER 10197: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF SKIN BUYER OF TRADE-IT POSSESSION OF SWEET CHESNUT TREE INNER BARK 10607: A HUMAN BEING IN 10086: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF RASPBERRY PLANT BARK POSSESSION OF ASH TREE WOOD 09148: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF AN OPTICAL LENS 09472: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A SUNLIGHT FIRE LIGHTER 09149: A HUMAN BEING LOCATED 01552: A HUMAN BEING IN IN DIRECT SUNLIGHT POSSESSION OF A KNIFE 09471: A HUMAN BEING IN 09720: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE DRILL FIRE POSSESSION OF LIME TREE WOOD LIGHTER 09479: A HUMAN BEING IN 10314: A HUMAN BEING IN 09965: A HUMAN BEING IN OR OR AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE PLOUGH FIRE POSSESSION OF HAWTHORN TREE WOOD POSSESSION OF A WOOD ROD LIGHTER 10182: -

Pomo.' Habe'napo (Ha), "Rock-People," Is the Name of a Group, Not of a Village Site

CULTURE ELEMENT .DISTRIg1UTI:ONS: IJV ~OMlO BY E. W. GIIPFORD -AND A. L. ~KROEBBER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATI'ONs IN ,AmERICAN AIpcamLoay AND ]IRTHNOLOGY, Volme 7, No. 4, pp 117-254 11 tables, 6 fi'gu'res, 1 map UNIVEBRSITY Of CALIFORNIA PRESS -BER-KELEY, CALIFORNIA, POlMO --- POMO COMMUNITIES CULTURE ELEMENT DISTRIBUTIONS: IV POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD AND A. L. KROEBER UNRVSITY 01POFCAjORNIA PUBLiCATIONS IN AMuaICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY Volume 37, No. 4, pp. 117-254, 11 tables, 6 figures Issued July 1, 1937 Price, $1.50 UNIVERSITY OP CALnIORNiu Puzss BEKrLEY, CATropwu CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSrrY PR&ss LONDON, ENGLAND PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES Or AMERICA CONTENTS PAGE Introduction .................................................... 117 PART I: DATA, BY E. W. GIFFORD Pomo communities ................................................ 117 Informants .................................................... 122 Element occurrence list ........................................... 125 Symbols used .................................................. 126 Elements lacking among the Pomo ................................. 165 Supplementary notes: Pomo ....................................... 167 Supplementary notes: Wintun, Patwin, Miwok ...................... 214 PART II: ANALYSIS, bY A. L. KROEBER Reliability .................................................... 223 Method of analysis ................................................ 2-229 Reliability again ................................................. 236 Ethnographic interpretation ...................................... -

Scouts Survival Skills Badge Demonstrate Different Techniques to Light a Fire Fire Techs Competition Manual©

Scouts Survival Skills Badge Demonstrate Different Techniques To Light A Fire Fire Techs Competition Manual© By Samantha Eagle © All Rights Reserved 2019 Copyright Notices © Copyright Samantha Eagle All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The purchaser is authorised to use any of the information in this publication for his or her own use ONLY. For example, if you are a leader trainer you are within your rights to show any or all of the material to other leaders within your possession. However, it is strictly prohibited to copy and share any of the materials with other leaders or anyone. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to [email protected] Published by Samantha Eagle PO Box 245, La Manga Club Murcia, 30389, Spain. Email: [email protected] Legal Notices While all attempts have been made to verify information provided in this publication, neither Author nor the Publisher assumes any responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretation of the subject matter given in this product. Page | 1 © All Rights Reserved 2018 EasierScouting.com Fire Techs Competition Manual© Preparing a Tinder Nest 1. Before you start a fire you will need a properly prepared ‘Tinder Nest’ this can mean the difference between the warm glow of success and cold sting of failure with fire! A ‘Tinder Nest’ can consist of soft dried natural materials for example, Dry grass, Cattail fluff, Birch tree bark and Dandelion clock Dry Grass The head of the Cattail after Birch Tree Bark Dandelion Clock it has turned dark brown will have “fluff” inside, which is excellent tinder 2. -

2006. Making Fire

Stephen Blake and David M. Welch AN ESSENTIAL SURVIVAL GUIDE tephen Blake demonstrates S four ways of making fire, rubbing two sticks together using the hand drill, bow drill, fire saw and fire plough methods. David Welch discusses fire making amongst indigenous , people of the world, from ancient times, and in particular amongst Australia's Aborigines. Making fire is a basic survival skill, a way of attracting attention if one is lost alone in remote bushland. Shown here without using modern tools, it is possible to use crude pieces of rock to fashion fire sticks and from these, to make fire. ISBN 0-9775035-1-8 9 780977 503513 ~s itten co~~-- Introduction . 1 Terminology and Technology 3 ;. Chapter 1 Ancient Fire Making s Chapter ~ Australian Aboriginal Fire Making 17 Chapter j The Hand Drill 33 Chapter 4 The Bow Drill 59 ..,_ Chapter 5 The Fire Saw , ;:, Chapter ~ The Fire Plough 83 Chapter 7 Making a camp fire - Steve's method 89 References, acknowledgments and photo credits 98 Wtl;wlvdlrr/l--- his book combines two aspects of making fire from two T authors. Stephen Blake gives practical advice on how to achieve the ancient craft of lighting a fire by rubbing two sticks together. Four methods, the hand drill, the bow drill, the fire saw and the fire plough are described in detail and demonstrated by him (Chapters three to six). David Welch offers an account of fire making throughout mankind's history, describing the methods used by indigenous people around the world and illustrating the various methods used by Australia's Aborigines (Chapters one and two). -

Natural and Cultural History of the Marquesas Islands

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. The role of arboriculture in landscape domestication and agronomic development: A case study from the Marquesas Islands, East Polynesia Jennifer Marie Huebert A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology, The University of Auckland, 2014. Abstract Polynesian settlers transformed the native forests of the central Pacific islands into productive economic landscapes. Root crops came to dominate agronomic systems in many areas but arboriculture was the dominant mode of food production in some, and it is not well understood how these different endpoints evolved. -

Building a Fire

The Forest School Training Co. OCN accredited training The Science of Fire What is Fire?! We can see the multi-coloured flames, the glowing embers and charring fuel. We can hear the crackling and popping of wood, smell the swirling smoke and feel the warmth coming from it, perhaps even taste the food that has been cooked on it. Fire will mean something different to each of us. It is something that we are all instinctually connected to, but what is it? From a scientific perspective; fire is a chemical reaction between oxygen and a fuel source (oxidation), and there are actually 2 separate reactions occurring. The result is exothermic (meaning it gives out energy in the form of heat and light). There is a sequence of events; 1. Something heats the fuel (let’s say wood), this heat source could come from varying places (see fire lighting below) 2. Once the wood gets to about 1500C, the cellulose in it starts to decompose and releases volatile gases (which we refer to as smoke). These volatile gases or smoke are compounds made up of the elements hydrogen (H), carbon (C) and Oxygen (O). 3. Once the gases are released the rest of the fuel material forms char, which is nearly pure carbon (C) and ash, which is all the unburnable minerals in the fuel (like calcium, potassium etc). 6C10H15O7 (Wood) + Heat C50H10O (Char) + 10CH2O (Gas) 4. Once the volatile gases (smoke) reach about 2600C the compound breaks apart and a second chemical reaction occurs with the oxygen in the atmosphere to create water, carbon dioxide and other waste products. -

Early Light Cards © 2009 Energy Lights Maine

Energy Lights Maine This small pottery lamp made out of clay burned animal fat and plant oils. Lamps like these were first used in the first century A.D. by Egyptians. Some of the oldest oil lamps were made using rocks and shells. A stick rubbed very quickly against another piece Using oil as a fuel for light can be difficult to do. of wood can become hot enough to make tinder The oil must be very hot before it will burn. catch on fire. How does this happen? Why would this be a problem? Native people mastered the art of starting a fire People learned to use a “wick” – a thin cord of without matches using a fire plough and hearth or absorbent material that soaks up the oil so that it bow and hand drill. These techniques are still used burns a little at a time. Rock, shell, and pottery by people today, including Maine sportsmen and lamps were the first step toward the invention of sportswomen today. the oil lamp. During the 19th century, American cities and towns used gas lamps to light their streets. Because of Did you know that matches create a flame by a this streets were finally able to be lit at night. chemical reaction? Match heads are coated with People were glad that their streets weren’t so dark a material called phosphorus. This phosphorus anymore. ignites from the heat of the friction as it is struck These gaslights were made from iron and copper against a surface. and had to be lit by hand.