Site Report: Lucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Is an Update of the Paper Presented by Dave Greenfield and Ron Ryczak of BAMR at the 2008 NAAMLP Conference in Durango, Colorado

Assessment of Fluvial Geomorphology Projects at Abandoned Mine Sites in 1 the Anthracite Region of Pennsylvania Dennis M. Palladino, P.E.² Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation 2 Public Square, Wilkes-Barre, PA 18701-1915 [email protected] (570) 830-3190 ABSTRACT Some watersheds have been so severely impacted by mining that the streams do not support aquatic life and can no longer accommodate flows or transport sediment. To fully recover the environmental resource of these scarred landscapes the land must be reclaimed and the streams reconstructed. As abandoned mine sites are being reclaimed to their approximate original contours, the hydrology of the watersheds will be returning to pre-mining conditions and generating base flows and storm discharges that residents may not have experienced in many years. A stable system will have to be designed to transport the flows and sediment while preventing erosion and flooding. Traditionally, rigid systems have been implemented that are rectangular or trapezoidal in shape and are constructed entirely of rock and concrete. These systems have a good survival rate but do not replace the resource that was lost during mining. In an attempt to reclaim the watersheds that were destroyed during mining to a natural state, the application of Fluvial Geomorphologic (FGM) techniques has been embraced at several sites in the Anthracite Region of Pennsylvania. These sites have had various degrees of success. All of the sites were designed based on bankfull conditions and were immediately successful in creating habitat for a wide variety of species. Some sites remained stable until damaged due to extreme discharge events where design, construction, or implementation flaws were revealed in regions above the bankfull elevation. -

NPDES) INDIVIDUAL PERMIT to DISCHARGE STORMWATER from SMALL MUNICIPAL SEPARATE STORM SEWER SYSTEMS (Ms4s

3800-PM-BCW0200e Rev. 8/2019 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Permit DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION BUREAU OF CLEAN WATER NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM (NPDES) INDIVIDUAL PERMIT TO DISCHARGE STORMWATER FROM SMALL MUNICIPAL SEPARATE STORM SEWER SYSTEMS (MS4s) NPDES PERMIT NO. PAI132224 In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. Section 1251 et seq. (“the Act”) and Pennsylvania’s Clean Streams Law, as amended, 35 P.S. Section 691.1 et seq., Lackawanna County 1280 Mid Valley Drive Jessup, PA 18434-1819 is authorized to discharge from a regulated small municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) located in Lackawanna County to Roaring Brook (CWF, MF), Powderly Creek (CWF, MF), Lackawanna River (HQ-CWF, MF), Unnamed Tributary to Lucky Run (CWF, MF), Wildcat Creek (CWF, MF), Keyser Creek (CWF, MF), Unnamed Tributary to Stafford Meadow Brook (HQ-CWF, MF), and Unnamed Stream (CWF, MF) in Watersheds 5-A in accordance with effluent limitations, monitoring requirements and other conditions set forth herein. THIS PERMIT SHALL BECOME EFFECTIVE ON MAY 1, 2021 THIS PERMIT SHALL EXPIRE AT MIDNIGHT ON APRIL 30, 2026 The authority granted by coverage under this Permit is subject to the following further qualifications: 1. The permittee shall comply with the effluent limitations and reporting requirements contained in this permit. 2. The application and its supporting documents are incorporated into this permit. If there is a conflict between the application, its supporting documents and/or amendments and the terms and conditions of this permit, the terms and conditions shall apply. 3. Failure to comply with the terms, conditions or effluent limitations of this permit is grounds for enforcement action; for permit termination, revocation and reissuance, or modification; or for denial of a permit renewal application. -

NPDES) INDIVIDUAL PERMIT to DISCHARGE STORMWATER from SMALL MUNICIPAL SEPARATE STORM SEWER SYSTEMS (Ms4s

3800-PM-BCW0200e Rev. 8/2019 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Permit DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION BUREAU OF CLEAN WATER NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM (NPDES) INDIVIDUAL PERMIT TO DISCHARGE STORMWATER FROM SMALL MUNICIPAL SEPARATE STORM SEWER SYSTEMS (MS4s) NPDES PERMIT NO. PAI132224 In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. Section 1251 et seq. (“the Act”) and Pennsylvania’s Clean Streams Law, as amended, 35 P.S. Section 691.1 et seq., Lackawanna County 1280 Mid Valley Drive Jessup, PA 18434-1819 is authorized to discharge from a regulated small municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) located in Lackawanna County to Roaring Brook (CWF, MF), Powderly Creek (CWF, MF), Lackawanna River (HQ-CWF, MF), Unnamed Tributary to Lucky Run (CWF, MF), Wildcat Creek (CWF, MF), Keyser Creek (CWF, MF), Unnamed Tributary to Stafford Meadow Brook (HQ-CWF, MF), and Unnamed Stream (CWF, MF) in Watersheds 5-A in accordance with effluent limitations, monitoring requirements and other conditions set forth herein. THIS PERMIT SHALL BECOME EFFECTIVE ON TBD THIS PERMIT SHALL EXPIRE AT MIDNIGHT ON TBD The authority granted by coverage under this Permit is subject to the following further qualifications: 1. The permittee shall comply with the effluent limitations and reporting requirements contained in this permit. 2. The application and its supporting documents are incorporated into this permit. If there is a conflict between the application, its supporting documents and/or amendments and the terms and conditions of this permit, the terms and conditions shall apply. 3. Failure to comply with the terms, conditions or effluent limitations of this permit is grounds for enforcement action; for permit termination, revocation and reissuance, or modification; or for denial of a permit renewal application. -

On the Evolution of Human Fire Use

ON THE EVOLUTION OF HUMAN FIRE USE by Christopher Hugh Parker A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology The University of Utah May 2015 Copyright © Christopher Hugh Parker 2015 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Christopher Hugh Parker has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Kristen Hawkes , Chair 04/22/2014 Date Approved James F. O’Connell , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Henry Harpending , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Andrea Brunelle , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Rebecca Bliege Bird , Member Date Approved and by Leslie A. Knapp , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Anthropology and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Humans are unique in their capacity to create, control, and maintain fire. The evolutionary importance of this behavioral characteristic is widely recognized, but the steps by which members of our genus came to use fire and the timing of this behavioral adaptation remain largely unknown. These issues are, in part, addressed in the following pages, which are organized as three separate but interrelated papers. The first paper, entitled “Beyond Firestick Farming: The Effects of Aboriginal Burning on Economically Important Plant Foods in Australia’s Western Desert,” examines the effect of landscape burning techniques employed by Martu Aboriginal Australians on traditionally important plant foods in the arid Western Desert ecosystem. The questions of how and why the relationship between landscape burning and plant food exploitation evolved are also addressed and contextualized within prehistoric demographic changes indicated by regional archaeological data. -

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1967 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Advisory Editors: M. A. Baumhoff, D. J. Crowley, C. J. Erasmus, T. D. McCown, C. W. Meighan, H. P. Phillips, M. G. Smith Volume 25 Approved for publication May 20, 1966 Issued May 29, 1967 Price, $1.50 University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles C alifornia Cambridge University Press London, England Manufactured in the United States of America CONTENTS Introduction ............................................ 1 The Southwestern Pomo in Russian Times: An Account by Kostromitonow ..1 Data Obtained from Herman James ..5 Neighboring Indian Groups .. 5 Informants ..5 Orthography ..6 Habitat .. 7 Village Sites ..7 Ethnobotany ..10 Ethnozoology. .16 Mammals .16 Birds. 17 Reptiles and batrachians .19 Fishes . 19 Insects and other terrestrial invertebrates. 20 Marine invertebrates .20 Culture Element List .21 Notes on culture element list .38 Appendix: Comparative Notes on Two Historic Village Sites by Clement W. Meighan. 46 Works Cited .............................................. 48 [ v ] ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD INTRODUCTION* The Southwestern Pomo were among the most primitive Charles Haupt married a woman from Chibadono of the California aborigines, a fact to be correlated with [ci'?bad6no] (near Plantation and on the same ridge). She their mountainous terrain on a rugged, inhospitable coast. was called Pashikokoya [pasilk6?koya? ], "cocoon woman" Their low culture may be contrasted with the richer cul- (pashikoyoyu [pa'si-oyo-yu], cocoon used on shaman' s ture of the Pomo of the Russian River Valley and Clear rattle; ya?, personal suffix), but her English name was Lake, environments which offered opportunities for Molly. -

Low-Impact Living Initiative

firecraft what is it? It's starting and managing fire, which requires fuel, oxygen and ignition. The more natural methods usually progress from a spark to an ember to a flame in fine, dry material (tinder), to small, thin pieces of wood (kindling) and then to firewood. Early humans collected embers from forest fires, lightning strikes and even volcanic activity. Archaeological evidence puts the first use of fire between 200-400,000 years ago – a time that corresponds to a change in human physique consistent with food being cooked - e.g. smaller stomachs and jaws. The first evidence of people starting fires is from around 10,000 years ago. Here are some ways to start a fire. Friction: rubbing things together to create friction Sitting around a fire has been a relaxing, that generates heat and produces embers. An comforting and community-building activity for example is a bow-drill, but any kind of friction will many millennia. work – e.g. a fire-plough, involving a hardwood stick moving in a groove in a piece of softwood. what are the benefits? Percussion: striking things together to make From an environmental perspective, the more sparks – e.g. flint and steel. The sharpness of the natural the method the better. For example, flint creates sparks - tiny shards of hot steel. strikers, fire pistons or lenses don’t need fossil Compression: fire pistons are little cylinders fuels or phosphorus, which require the highly- containing a small amount of tinder, with a piston destructive oil and chemical industries, and that is pushed hard into the cylinder to compress friction methods don’t require the mining, factories the air in it, which raises pressure and and roads required to manufacture anything at all. -

Stormwater Management

City of Alexandria, VA Proposed FY 2021 - FY 2030 Capital Improvement Program STORMWATER MANAGEMENT Stormwater Management Page 15.1 City of Alexandria, VA Proposed FY 2021 - FY 2030 Capital Improvement Program Note: Projects with a $0 total funding are active capital projects funded in prior CIP's that do not require additional resources. FY 2020 and FY 2021 - Before FY 2021 FY 2022 FY 2023 FY 2024 FY 2025 FY 2026 FY 2027 FY 2028 FY 2029 FY 2030 FY 2030 Stormwater Management Cameron Station Pond Retrofit 4,681,8850000000000 0 City Facilities Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMPs) 1,633,0000000000000 0 Four Mile Run Channel Maintenance 3,293,000 0 0 936,60000001,251,300 4,177,000 0 6,364,900 Green Infrastructure 1,850,000 206,500 210,000 0 1,549,0000000001,965,500 Lucky Run Stream Restoration 2,800,0000000000000 0 MS4-TDML Compliance Water Quality Improvements 1,255,000 3,000,000 3,500,000 3,500,000 7,000,000 7,000,000 7,000,000 9,000,000 5,000,000 3,000,000 3,000,000 51,000,000 NPDES / MS4 Permit 815,000 165,000 170,000 168,400 170,000 171,700 173,500 175,200 177,000 178,700 180,500 1,730,000 Phosphorus Exchange Bank 00000000000 0 Storm Sewer Capacity Assessment 4,713,500 498,750 508,300 0 0 7,529,100 0 588,100 10,213,900 0 0 19,338,150 Storm Sewer System Spot Improvements 7,605,221 420,000 430,500 441,400 452,500 464,000 475,800 488,000 500,500 513,400 526,700 4,712,800 Stormwater BMP Maintenance CFMP 135,000 140,000 144,200 148,600 153,000 1,201,500 1,220,100 157,700 160,900 164,100 167,400 3,657,500 Stormwater Utility Implementation -

Fire Before Matches

Fire before matches by David Mead 2020 Sulang Language Data and Working Papers: Topics in Lexicography, no. 34 Sulawesi Language Alliance http://sulang.org/ SulangLexTopics034-v2 LANGUAGES Language of materials : English ABSTRACT In this paper I describe seven methods for making fire employed in Indonesia prior to the introduction of friction matches and lighters. Additional sections address materials used for tinder, the hearth and its construction, some types of torches and lamps that predate the introduction of electricity, and myths about fire making. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction; 2 Traditional fire-making methods; 2.1 Flint and steel strike- a-light; 2.2 Bamboo strike-a-light; 2.3 Fire drill; 2.4 Fire saw; 2.5 Fire thong; 2.6 Fire plow; 2.7 Fire piston; 2.8 Transporting fire; 3 Tinder; 4 The hearth; 5 Torches and lamps; 5.1 Palm frond torch; 5.2 Resin torch; 5.3 Candlenut torch; 5.4 Bamboo torch; 5.5 Open-saucer oil lamp; 5.6 Footed bronze oil lamp; 5.7 Multi-spout bronze oil lamp; 5.8 Hurricane lantern; 5.9 Pressurized kerosene lamp; 5.10 Simple kerosene lamp; 5.11 Candle; 5.12 Miscellaneous devices; 6 Legends about fire making; 7 Additional areas for investigation; Appendix: Fire making in Central Sulawesi; References. VERSION HISTORY Version 2 [13 June 2020] Minor edits; ‘candle’ elevated to separate subsection. Version 1 [12 May 2019] © 2019–2020 by David Mead All Rights Reserved Fire before matches by David Mead Down to the time of our grandfathers, and in some country homes of our fathers, lights were started with these crude elements—flint, steel, tinder—and transferred by the sulphur splint; for fifty years ago matches were neither cheap nor common. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

AL Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source

Masks and Moieties as a Culture Complex. Author(s): A. L. Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 50 (Jul. - Dec., 1920), pp. 452-460 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843493 Accessed: 01-02-2016 04:49 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 204.235.148.92 on Mon, 01 Feb 2016 04:49:06 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 452 MASKS AND MOIETIES AS A CULTURE COMPLEX. By A. L. KROEBERAND CATHARINEHOLT. IN 1905, Graebnerand Ankermannpublished synchronous articlesL in which they distinguisheda nlumberof successivelayers of culturein Oceania and Africa. This scheme Graebnersubsequently developed in an essay which traced at least some of these culturestrata as far as America.2 Graebner'stheory has been accepted, with or without reservations,by a number of authorities,including Foy,3 W. -

A1128 Able to Light a Fire Map of Influence

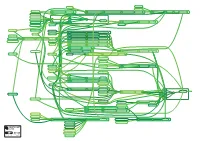

11591: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A LIMPET SHELL 12278: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A SAW 12113: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A MUSSEL SHELL 09112: A HUMAN BEING CUSTOMER 09475: A HUMAN BEING IN 12729: A HUMAN BEING IN 12281: A HUMAN BEING IN OF WH SMITH OR OR AND OR OR POSSESSION OF A ELASTIC BAND POSSESSION OF A WOOD WASHER AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE BOW DRILL FIRE LIGHTER 10630: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CHERRY TREE OUTER BARK 12394: A HUMAN BEING IN OR POSSESSION OF A RIBWORT PLANTAIN PLANT LEAF 11946: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND OR POSSESSION OF STINGING NETTLE PLANT BARK 09477: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CORDAGE 11550: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR 10437: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND POSSESSION OF A BOW POSSESSION OF WHITE WILLOW TREE INNER BARK 13740: A HUMAN BEING IN 00924: A HUMAN BEING USER 10197: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF SKIN BUYER OF TRADE-IT POSSESSION OF SWEET CHESNUT TREE INNER BARK 10607: A HUMAN BEING IN 10086: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF RASPBERRY PLANT BARK POSSESSION OF ASH TREE WOOD 09148: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF AN OPTICAL LENS 09472: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A SUNLIGHT FIRE LIGHTER 09149: A HUMAN BEING LOCATED 01552: A HUMAN BEING IN IN DIRECT SUNLIGHT POSSESSION OF A KNIFE 09471: A HUMAN BEING IN 09720: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE DRILL FIRE POSSESSION OF LIME TREE WOOD LIGHTER 09479: A HUMAN BEING IN 10314: A HUMAN BEING IN 09965: A HUMAN BEING IN OR OR AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE PLOUGH FIRE POSSESSION OF HAWTHORN TREE WOOD POSSESSION OF A WOOD ROD LIGHTER 10182: -

SPECIAL SESSION FLOOD CONTROL and HAZARD MITIGATION ITEMIZATION ACT of 1996 Act of Jul

SPECIAL SESSION FLOOD CONTROL AND HAZARD MITIGATION ITEMIZATION ACT OF 1996 Act of Jul. 11, 1996, Special Session 2, P.L. 1791, No. 8 Cl. 86 Special Session No. 2 of 1996 No. 1996-8 AN ACT Itemizing public improvement projects for flood protection and flood damage repair to be constructed by the Department of General Services, together with their estimated financial costs; authorizing the use of disaster assistance bond funding for financing the projects to be constructed by the Department of General Services; stating the estimated useful life of the projects; making an appropriation; providing for the adoption of specific blizzard or flood mitigation projects or flood assistance projects to be financed from current revenues or from debt incurred under clause (1) of subsection (a) of section 7 of Article VIII of the Constitution of Pennsylvania; and making repeals. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS Section 101. Short title. This act shall be known and may be cited as the Special Session Flood Control and Hazard Mitigation Itemization Act of 1996. CHAPTER 3 FLOOD CAPITAL BUDGET PROJECT ITEMIZATIONS Section 301. Short title of chapter. This chapter shall be known and may be cited as the Special Session Flood Capital Budget Project Itemization Act of 1996. Section 302. Construction of chapter. The provisions of this chapter shall be construed unless specifically provided otherwise as a supplement to the act of July 6, 1995 (P.L.269, No.38), known as the Capital Budget Act of 1995-1996. Section 303. Total authorization.