1999 Revision of the FAO Wildland Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fire Extinguisher Booklet

NY Fire Consultants, Inc. NY Fire Safety Institute 481 Eighth Avenue, Suite 618 New York, NY 10001 (212) 239 9051 (212) 239 9052 fax Fire Extinguisher Training The Fire Triangle In order to understand how fire extinguishers work, you need to understand some characteristics of fire. Four things must be present at the same time in order to produce fire: 1. Enough oxygen to sustain combustion, 2. Enough heat to raise the material to its ignition temperature, 3. Some sort of fuel or combustible material, and 4. The chemical, exothermic reaction that is fire. Oxygen, heat, and fuel are frequently referred to as the "fire triangle." Add in the fourth element, the chemical reaction, and you actually have a fire "tetrahedron." The important thing to remember is: take any of these four things away, and you will not have a fire or the fire will be extinguished. Essentially, fire extinguishers put out fire by taking away one or more elements of the fire triangle/tetrahedron. Fire safety, at its most basic, is based upon the principle of keeping fuel sources and ignition sources separate Not all fires are the same, and they are classified according to the type of fuel that is burning. If you use the wrong type of fire extinguisher on the wrong class of fire, you can, in fact, make matters worse. It is therefore very important to understand the four different fire classifications. Class A - Wood, paper, cloth, trash, plastics Solid combustible materials that are not metals. (Class A fires generally leave an Ash.) Class B - Flammable liquids: gasoline, oil, grease, acetone Any non-metal in a liquid state, on fire. -

On the Evolution of Human Fire Use

ON THE EVOLUTION OF HUMAN FIRE USE by Christopher Hugh Parker A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology The University of Utah May 2015 Copyright © Christopher Hugh Parker 2015 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Christopher Hugh Parker has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Kristen Hawkes , Chair 04/22/2014 Date Approved James F. O’Connell , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Henry Harpending , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Andrea Brunelle , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Rebecca Bliege Bird , Member Date Approved and by Leslie A. Knapp , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Anthropology and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Humans are unique in their capacity to create, control, and maintain fire. The evolutionary importance of this behavioral characteristic is widely recognized, but the steps by which members of our genus came to use fire and the timing of this behavioral adaptation remain largely unknown. These issues are, in part, addressed in the following pages, which are organized as three separate but interrelated papers. The first paper, entitled “Beyond Firestick Farming: The Effects of Aboriginal Burning on Economically Important Plant Foods in Australia’s Western Desert,” examines the effect of landscape burning techniques employed by Martu Aboriginal Australians on traditionally important plant foods in the arid Western Desert ecosystem. The questions of how and why the relationship between landscape burning and plant food exploitation evolved are also addressed and contextualized within prehistoric demographic changes indicated by regional archaeological data. -

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1967 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Advisory Editors: M. A. Baumhoff, D. J. Crowley, C. J. Erasmus, T. D. McCown, C. W. Meighan, H. P. Phillips, M. G. Smith Volume 25 Approved for publication May 20, 1966 Issued May 29, 1967 Price, $1.50 University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles C alifornia Cambridge University Press London, England Manufactured in the United States of America CONTENTS Introduction ............................................ 1 The Southwestern Pomo in Russian Times: An Account by Kostromitonow ..1 Data Obtained from Herman James ..5 Neighboring Indian Groups .. 5 Informants ..5 Orthography ..6 Habitat .. 7 Village Sites ..7 Ethnobotany ..10 Ethnozoology. .16 Mammals .16 Birds. 17 Reptiles and batrachians .19 Fishes . 19 Insects and other terrestrial invertebrates. 20 Marine invertebrates .20 Culture Element List .21 Notes on culture element list .38 Appendix: Comparative Notes on Two Historic Village Sites by Clement W. Meighan. 46 Works Cited .............................................. 48 [ v ] ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD INTRODUCTION* The Southwestern Pomo were among the most primitive Charles Haupt married a woman from Chibadono of the California aborigines, a fact to be correlated with [ci'?bad6no] (near Plantation and on the same ridge). She their mountainous terrain on a rugged, inhospitable coast. was called Pashikokoya [pasilk6?koya? ], "cocoon woman" Their low culture may be contrasted with the richer cul- (pashikoyoyu [pa'si-oyo-yu], cocoon used on shaman' s ture of the Pomo of the Russian River Valley and Clear rattle; ya?, personal suffix), but her English name was Lake, environments which offered opportunities for Molly. -

Low-Impact Living Initiative

firecraft what is it? It's starting and managing fire, which requires fuel, oxygen and ignition. The more natural methods usually progress from a spark to an ember to a flame in fine, dry material (tinder), to small, thin pieces of wood (kindling) and then to firewood. Early humans collected embers from forest fires, lightning strikes and even volcanic activity. Archaeological evidence puts the first use of fire between 200-400,000 years ago – a time that corresponds to a change in human physique consistent with food being cooked - e.g. smaller stomachs and jaws. The first evidence of people starting fires is from around 10,000 years ago. Here are some ways to start a fire. Friction: rubbing things together to create friction Sitting around a fire has been a relaxing, that generates heat and produces embers. An comforting and community-building activity for example is a bow-drill, but any kind of friction will many millennia. work – e.g. a fire-plough, involving a hardwood stick moving in a groove in a piece of softwood. what are the benefits? Percussion: striking things together to make From an environmental perspective, the more sparks – e.g. flint and steel. The sharpness of the natural the method the better. For example, flint creates sparks - tiny shards of hot steel. strikers, fire pistons or lenses don’t need fossil Compression: fire pistons are little cylinders fuels or phosphorus, which require the highly- containing a small amount of tinder, with a piston destructive oil and chemical industries, and that is pushed hard into the cylinder to compress friction methods don’t require the mining, factories the air in it, which raises pressure and and roads required to manufacture anything at all. -

Types of Fire Extinguisher in Australia – All You Need to Know (February 02

Types of fire extinguisher in Australia – all you need to know (February 02, 2018) There are 5 main fire extinguisher types in Australia – Water, Foam, Dry Powder, CO2 and Wet Chemical. You should have the right types of fire extinguisher for your house or business premises, or you may not meet current regulations. The various types of fire extinguisher put out fires started with different types of fuel – these are called ‘classes’ of fire. The fire risk from the different classes of fire in your home or your business premises will determine which fire extinguisher types you need. You will also need to make sure that you have the right size and weight of fire extinguisher as well as the right kind. Whilst there are 5 main types of fire extinguisher, there are different versions of Dry Powder extinguishers, meaning there are a total of 8 fire extinguisher types to choose from. The 6 types of fire extinguisher are: – Water – Foam – Dry Powder – Standard – Dry Powder – High performance – Carbon Dioxide (‘CO2’) – Wet Chemical There is no one extinguisher type which works on all classes of fire. Below is a summary of the classes of fire, and a quick reference chart showing which types of extinguisher should be used on each. We then provide a detailed explanation of each type of fire extinguisher below. The classes of fire There are six classes of fire: Class A, Class B, Class C, Class D, ‘Electrical’, and Class F. – Class A fires – combustible materials: caused by flammable solids, such as wood, paper, and fabric – Class B fires – flammable liquids: such as petrol, turpentine or paint – Class C fires – flammable gases: like hydrogen, butane or methane – Class D fires – combustible metals: chemicals such as magnesium, aluminium or potassium – Electrical fires – electrical equipment: once the electrical item is removed, the fire changes class – Class F fires – cooking oils: typically a chip-pan fire Water and Foam Water and Foam fire extinguishers extinguish the fire by taking away the heat element of the fire triangle. -

The Use of Fire Classification in the Nordic Countries – Proposals

The use of fi re classifi cation in the Nordic countries – Proposals for harmonisation Per Thureson, Björn Sundström, Esko Mikkola, Dan Bluhme, Anne Steen Hansen and Björn Karlsson SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden SP Technical SP Fire Technology SP REPORT 2008:29 The use of fire classification in the Nordic countries - Proposals for harmonisation Per Thureson, Björn Sundström, Esko Mikkola, Dan Bluhme, Anne Steen Hansen and Björn Karlsson 2 Key words: harmonisation, fire classification, construction products, building regulations, reaction to fire, fire resistance SP Sveriges Tekniska SP Technical Research Institute of Forskningsinstitut Sweden SP Rapport 2008:29 SP Report 2008:29 ISBN 978-91-85829-46-0 ISSN 0284-5172 Borås 2008 Postal address: Box 857, SE-501 15 BORÅS, Sweden Telephone: +46 33 16 50 00 Telefax: +46 33 13 55 02 E-mail: [email protected] 3 Contents Contents 3 Preface 5 Summary 6 1 Nordic harmonisation of building regulations – earlier work 9 1.1 NKB 9 2 Building regulations in the Nordic countries 10 2.1 Levels of regulatory tools 10 2.2 Performance-based design and Fire Safety Engineering (FSE) 12 2.2.1 Fire safety and performance-based building codes 12 2.2.2 Verification 13 2.2.3 Fundamental principles of deterministic Fire Safety Engineering 15 2.3 The Construction Products Directive – CPD 16 3 Implementation of the CPD in the Nordic countries – present situation and proposals 18 3.1 Materials 18 3.2 Internal surfaces 22 3.3 External surfaces 24 3.4 Facades 26 3.5 Floorings 28 3.6 Insulation products 30 3.7 Linear -

Fire Before Matches

Fire before matches by David Mead 2020 Sulang Language Data and Working Papers: Topics in Lexicography, no. 34 Sulawesi Language Alliance http://sulang.org/ SulangLexTopics034-v2 LANGUAGES Language of materials : English ABSTRACT In this paper I describe seven methods for making fire employed in Indonesia prior to the introduction of friction matches and lighters. Additional sections address materials used for tinder, the hearth and its construction, some types of torches and lamps that predate the introduction of electricity, and myths about fire making. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction; 2 Traditional fire-making methods; 2.1 Flint and steel strike- a-light; 2.2 Bamboo strike-a-light; 2.3 Fire drill; 2.4 Fire saw; 2.5 Fire thong; 2.6 Fire plow; 2.7 Fire piston; 2.8 Transporting fire; 3 Tinder; 4 The hearth; 5 Torches and lamps; 5.1 Palm frond torch; 5.2 Resin torch; 5.3 Candlenut torch; 5.4 Bamboo torch; 5.5 Open-saucer oil lamp; 5.6 Footed bronze oil lamp; 5.7 Multi-spout bronze oil lamp; 5.8 Hurricane lantern; 5.9 Pressurized kerosene lamp; 5.10 Simple kerosene lamp; 5.11 Candle; 5.12 Miscellaneous devices; 6 Legends about fire making; 7 Additional areas for investigation; Appendix: Fire making in Central Sulawesi; References. VERSION HISTORY Version 2 [13 June 2020] Minor edits; ‘candle’ elevated to separate subsection. Version 1 [12 May 2019] © 2019–2020 by David Mead All Rights Reserved Fire before matches by David Mead Down to the time of our grandfathers, and in some country homes of our fathers, lights were started with these crude elements—flint, steel, tinder—and transferred by the sulphur splint; for fifty years ago matches were neither cheap nor common. -

AL Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source

Masks and Moieties as a Culture Complex. Author(s): A. L. Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 50 (Jul. - Dec., 1920), pp. 452-460 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843493 Accessed: 01-02-2016 04:49 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 204.235.148.92 on Mon, 01 Feb 2016 04:49:06 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 452 MASKS AND MOIETIES AS A CULTURE COMPLEX. By A. L. KROEBERAND CATHARINEHOLT. IN 1905, Graebnerand Ankermannpublished synchronous articlesL in which they distinguisheda nlumberof successivelayers of culturein Oceania and Africa. This scheme Graebnersubsequently developed in an essay which traced at least some of these culturestrata as far as America.2 Graebner'stheory has been accepted, with or without reservations,by a number of authorities,including Foy,3 W. -

Managing Fire and Fuels in the Remaining Wildlands and Open Spaces of the Southwestern United States

United States Department of Proceedings of the 2002 Agriculture Forest Service Fire Conference: Managing Pacific Southwest Fire and Fuels in the Research Station Remaining Wildlands General Technical Report PSW-GTR-189 and Open Spaces of the August 2008 Southwestern United States D E E P R A U R T LT MENT OF AGRICU The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and National Grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation.The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250- 9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. -

Dampers and Actuators Catalog for the Latest Product Updates, Visit Us Online at > Johnsoncontrols.Com

Dampers and Actuators Catalog for the latest product updates, visit us online at > johnsoncontrols.com > johnsoncontrols.com > Building Efficiency > Integrated HVAC Systems > HVAC Control Products > Rectangular Dampers > Round Dampers > Air Control Products II Johnson Controls delivers products, services and solutions that increase energy efficiency and lower operating costs in buildings for more than one million customers. Operating from 500 branch offices in 148 countries, we are a leading provider of equipment, controls and services for heating, ventilating, air-conditioning, refrigeration and security systems. We have been involved in more than 500 renewable energy projects including solar, wind and geothermal technologies. Our solutions have reduced carbon dioxide emissions by 13.6 million metric tons and generated savings of $7.5 billion since 2000. Many of the world’s largest companies rely on us to manage 1.8 billion square feet of their commercial real estate. HVAC Dampers, Louvers and Air Control Products Since 1905, Johnson Controls has manufactured industry-leading temperature control dampers. Today, we offer a complete line of HVAC dampers and air control products including volume control, balancing, round, zone, fire, smoke and combined models. Johnson Controls is committed to customer satisfaction, and that’s why we custom-build each of our HVAC dampers to suit your specific size and model requirements. Some dampers can even be manufactured one day and shipped the next day. Actuators and accessories can be ordered with the damper and factory-installed or shipped separately depending on your needs. > Round Dampers III Introduction to Dampers The Selection Process Parallel vs Opposed Blade Operation Selecting the right damper is important to assure good Parallel blades rotate so they are always parallel to each operating characteristics in any airflow system, helping other; therefore, at any partially open position, they you maximize energy efficiency and minimize tend to redirect airflow and increase turbulence and installation costs. -

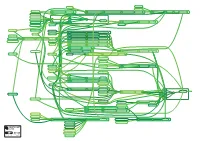

A1128 Able to Light a Fire Map of Influence

11591: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A LIMPET SHELL 12278: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A SAW 12113: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A MUSSEL SHELL 09112: A HUMAN BEING CUSTOMER 09475: A HUMAN BEING IN 12729: A HUMAN BEING IN 12281: A HUMAN BEING IN OF WH SMITH OR OR AND OR OR POSSESSION OF A ELASTIC BAND POSSESSION OF A WOOD WASHER AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE BOW DRILL FIRE LIGHTER 10630: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CHERRY TREE OUTER BARK 12394: A HUMAN BEING IN OR POSSESSION OF A RIBWORT PLANTAIN PLANT LEAF 11946: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND OR POSSESSION OF STINGING NETTLE PLANT BARK 09477: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CORDAGE 11550: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR 10437: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND POSSESSION OF A BOW POSSESSION OF WHITE WILLOW TREE INNER BARK 13740: A HUMAN BEING IN 00924: A HUMAN BEING USER 10197: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF SKIN BUYER OF TRADE-IT POSSESSION OF SWEET CHESNUT TREE INNER BARK 10607: A HUMAN BEING IN 10086: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF RASPBERRY PLANT BARK POSSESSION OF ASH TREE WOOD 09148: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF AN OPTICAL LENS 09472: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A SUNLIGHT FIRE LIGHTER 09149: A HUMAN BEING LOCATED 01552: A HUMAN BEING IN IN DIRECT SUNLIGHT POSSESSION OF A KNIFE 09471: A HUMAN BEING IN 09720: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE DRILL FIRE POSSESSION OF LIME TREE WOOD LIGHTER 09479: A HUMAN BEING IN 10314: A HUMAN BEING IN 09965: A HUMAN BEING IN OR OR AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE PLOUGH FIRE POSSESSION OF HAWTHORN TREE WOOD POSSESSION OF A WOOD ROD LIGHTER 10182: -

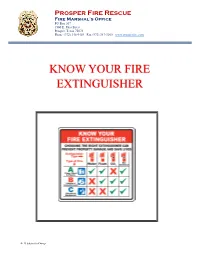

The Abcs of Fire-Extinguishers

Prosper Fire Rescue Fire Marshal’s Office PO Box 307 1500 E. First Street Prosper, Texas 75078 Phone (972) 346-9469 Fax (972) 347-3010 www.prosperfire.com KNOW YOUR FIRE EXTINGUISHER 10- 19 Subject to Change Fuel Classifications Not all fires are the same, they are classified according to the type of fuel that is burning. If you use the wrong type of fire extinguisher on the wrong class of fire, you can make matters worse. It is very important to understand the four different fire classifications. Class A - Wood, paper, cloth, trash, plastics Solid combustible materials that are not metals. (Class A fires generally leave an Ash.) Class B - Flammable liquids: gasoline, oil, grease, acetone Any non-metal in a liquid state, on fire. This classification also includes flammable gases. (Class B fires generally involve materials that Boil or Bubble.) Class C - Electrical: energized electrical equipment as long as it's "plugged in," it would be considered a class C fire. (Class C fires generally deal with electrical current.) Class D - Metals: potassium, sodium, aluminum, magnesium Unless you work in a laboratory or in an industry that uses these materials, it is unlikely you'll have to deal with a Class D fire. It takes special extinguishing agents (Metal-X, foam) to fight such afire. Most fire extinguishers will have a pictograph label telling you which classifications of fire the extinguisher is designed to fight. For example, a simple water extinguisher might have a label like the one below, indicating that it should only be used on Class A fires.