EXPLAINER: Shifting Power Plays in North and East Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin De Liaison Et D'information

INSTITUT KUDE RPARD IS E Bulletin de liaison et d’information N°364 JUILLET 2015 La publication de ce Bulletin bénéficie de subventions du Ministère français des Affaires étrangères (DGCID) et du Fonds d’action et de soutien pour l’intégration et la lutte contre les discriminations (FASILD) ————— Ce bulletin paraît en français et anglais Prix au numéro : France: 6 € — Etranger : 7,5 € Abonnement annuel (12 numéros) France : 60 € — Etranger : 75 € Périodique mensuel Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Numéro de la Commission Paritaire : 659 13 A.S. ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tél. : 01- 48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01- 48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: [email protected] Bulletin de liaison et d’information de l’Institut kurde de Paris N° 364 juillet 2015 • TURQUIE : VERS LA FIN DU PROCESSUS DU PAIX ? • SYRIE : LES KURDES FONT RECULER LE DAESH • KURDISTAN : POINT SUR LA GUERRE CONTRE LE DAESH • PARIS : MORT DU PEINTRE REMZI • CULTURE : LECTURES POUR L’ÉTÉ TURQUIE : VERS LA FIN DU PROCESSUS DU PAIX ? près le succès électoral GAP) élaboré dans les années Mais le projet du GAP ne datant du HDP, en juin der - 1970, prévoit la construction de pas d’hier, la déclaration du A nier, la situation sécuri - 22 barrages sur les bassins du KCK envisageant de reprendre taire au Kurdistan de Tigre et de l’ Euphrate , afin d’irri - les combats si d’autres barrages Turquie s’est dégradée guer 1,7 million d’hectares de étaient construits, doit plutôt être avec une telle violence que le terres et de fournir 746 MW four - considérée comme une réaction processus de paix initié par nis par 19 centrales hydroélec - de « l’aile dure » du PKK, cher - Öcalan et l’AKP en mars 2013 a triques . -

Fifth Report to Monitor the Spread of the Corona Epidemic in Syria

Fifth report to monitor the spread of the Corona epidemic in Syria April 17, 2020 Even as no confirmed cases of Covid-19 have been recorded thus far, there is a general unease and fear in the northwest and east of Syria about the pandemic and its possible effects on people in the region. There are precautions being taken in the northeast where awareness campaigns have been launched and curfews have been imposed. However, people in the northwest are not practicing any particular precautionary measures, with the exception of organizations working on the ground and local authorities. This report monitors the general situation of the epidemic and precautionary measures in all Syrian regions during the period of 10-17 April 2020. First: Northwest: The Northwest region is considered the most exposed to a possible outbreak of the Coronavirus epidemic which could result in dangerous consequences for the residents. Until the time of this report, no confirmed cases of Coronavirus have been recorded as the results of the total 133 tests conducted were all negative. The procedures in place in the region can be summarized as follows: - The suspension of work continued in schools and universities in Idlib and its countryside, and the Directorate of Education followed the method of distance education through the creation of groups and rooms on WhatsApp to follow up on students. Prayers in mosques also remained suspended for the second Friday in a row. - The Ministry of Health in the Provisional Government issued instructions for the medical staff to wear muzzles for the entire period of work and stop anyone not wearing masks from entering to any health facilities. -

Al-Qamishli the Syrian Kurdish Rebellion

Cities in Revolution Al-Qamishli The Syrian Kurdish Rebellion Researcher: Sabr Darwish Project leader: Mohammad Dibo Translator: Lilah Khoja Supported by Cities in Revolution حكاية ما انحكت SyriaUntold Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Introduction 3 Chapter One: The Uprising 5 I. The First Steps of the Uprising .............................................................5 II. Committees and the Parties .................................................................8 III. Challenging the City’s Elders ................................................................9 IV. The Weekly Demonstrations ...............................................................11 V. The Popular Movement’s Setbacks .....................................................14 Chapter Two: Recovery of Civil Society Organizations 19 I. Birati: Fraternity Foundation for Human Rights ...................................19 II. Shar for Development .........................................................................20 III. Other organizations .............................................................................22 Chapter Three: Autonomy in Al-Qamishli 25 I. Introduction ........................................................................................25 II. Democratic Self-Rule Project ..............................................................27 III. Fledgling Democratic Institutions ........................................................28 IV. Self-Rule and the Lack of Democracy ................................................30 V. Silencing -

Turkish Military and Islamic Groups Invasion in Northeast Syria

30.10.2019 Turkish military and Islamic groups invasion in Northeast Syria: On October 9, 2019 the Turkish army with Islamic allies started an offensive targeting mainly the area between Sere Kaniye and Tell Abiad. SDF in turn started to defend it. After few hours a massive displacement of population started toward south areas of Hasake, Raqqa, Ein issa and Tel Tamir. Below the detailed report day by day with photos and the casualties recorded. 25th- 30th of October,2019 Tiltamir people are fleeing as the heard Turkish army and Turkish backed group are close to the city. Situation of IDPs The number of counted IDPs just in Hassakeh City contains almost 3.000 families and around 11.500 individuals, from this number we have at least: 23 unaccompanied children, more than 5000 children between the ages 0-13, and more than 400 pregnant or breastfeeding women. Those IDPs are currently divided into around 60 schools. Many more families and individuals are displaced in and around Raqqa, Tabqa and Qamishli, and elsewhere. Many displaced families were able to find temporary accommodation at their relatives' or friends' houses. Some thousands arrived to northern Iraq to a formal camp of Mosul IDPs. This camp was not prepared to receive this high number of IDPs and is missing tents, WASH facilities as well as Health Care services and the provision of food and water. The biggest deficit for IDPs in Hassakeh is the lack of water, as well as WASH facilities and toilets, we are expecting outbreaks of diarrhea in the near future. -

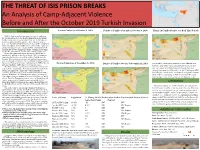

Methodology Results Introducfion Addifional Informafion Limitafions

THE THREAT OF ISIS PRISON BREAKS An Analysis of Camp-Adjacent Violence Before and After the October 2019 Turkish Invasion Faction Control (as of October 9, 2019) Density of Conflict (September 2-October 8, 2019) Change in Conflict Density over Both Time Periods Introduction With the Syrian conflict soon posed to enter its ninth year, the war has proven to be the greatest humanitarian and interna- tional security crisis in a generation. However, in the last year — at least in north-east of the country—there had been relative peace. The Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), along with American support, had consolidated its control of the region and all but rooted out the last remnants of ISIS. As of this fall, U.S. and SDF forces were engaged in counter-terrorism raids, ensur- ing that the now-stateless Islamic State remained suppressed. On the other side of the Syrian border sits Turkey, which considers the SDF to be directly tied to the PKK, a terrorist or- ganization that has been in conflict with the Turkish state for decades. This, combined with domestic political pressure to re- settle the millions of Syrian refugees currently residing within its borders, led Turkey to formulate a plan to invade SDF-held terri- Faction Control (as of November 16, 2019) Density of Conflict (October 9-November 16, 2019) records) while investigating potential escapes. Although over tory and establish a “buffer zone” in the border region. half of the total camps changed faction hands during the inva- The United States, eager to protect its wartime partners and to prevent the destabilizing effects of a Turkish incursion in the sion, none ended up in Turkish control. -

Kurds Kidnapped the Day While Maintaining the Ban on Its Civil Servants

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N°425 AUGUST 2020 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Culture & City of Paris ______________ This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: [email protected] Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 425 August 2020 • IRAQ: TWO OFFICERS OF THE IRAQI BORDER GUARDS KILLED BY A TURKISH DRONE • ROJAVA: KIDNAPPING, TORTURE, RAPE, MURDER... EVIDENCE OF THE CRIMES OF THE TURKISH OCCUPATION FORCES IS ACCUMULATING • TURKEY: EXACTIONS AGAINST WOMEN ARE MULTIPLE • IRAN: MASS TWITTER CAMPAIGN AGAINST THE ASSASSINATION OF KOLBARS, CALL FOR THE ACQUITTAL OF A KURDISH TEACHER • KURDISH LANGUAGE, PUBLICATIONS IRAQ: TWO OFFICERS OF THE IRAQI BORDER GUARDS KILLED BY A TURKISH DRONE ince the reopening of the to the Region from several Health called on cured patients to borders with Iran last countries, while conversely, donate their plasma for patients May, both Iraq and Turkey stopped flights to the developing severe forms of the Kurdistan are Region. Passengers leaving the infection. After more than twenty experiencing a dramatic Region must show a negative cases appeared, two villages in S increase in the figures of COVID test of less than 48 hours Akre district (Dohuk) were placed the pandemic.. -

Operation Inherent Resolve, Report to the United

OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS JULY 1, 2019‒OCTOBER 25, 2019 ABOUT THIS REPORT In January 2013, legislation was enacted creating the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations. This legislation, which amended the Inspector General Act, requires the Inspectors General of the Department of Defense (DoD), Department of State (DoS), and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to provide quarterly reports to Congress on overseas contingency operations. The DoD Inspector General (IG) is designated as the Lead IG for Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). The DoS IG is the Associate IG for OIR. The USAID IG participates in oversight for the operation. The Offices of Inspector General of the DoD, DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of OIR. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out their statutory missions to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the contingency operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the Federal Government in support of the contingency operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, and evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the contingency operation and activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, DoS, and USAID about OIR and related programs. The Lead IG agencies also gather data and information from open sources, including congressional testimony, policy research organizations, press conferences, think tanks, and media reports. -

Lead IG for Overseas Contingency Operations

LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL FOR OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS OCTOBER 1, 2016‒DECEMBER 31, 2016 LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL MISSION The Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations will coordinate among the Inspectors General specified under the law to: • develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight over all aspects of the contingency operation • ensure independent and effective oversight of all programs and operations of the federal government in support of the contingency operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, and investigations • promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness and prevent, detect, and deter fraud, waste, and abuse • perform analyses to ascertain the accuracy of information provided by federal agencies relating to obligations and expenditures, costs of programs and projects, accountability of funds, and the award and execution of major contracts, grants, and agreements • report quarterly and biannually to the Congress and the public on the contingency operation and activities of the Lead Inspector General (Pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978) FOREWORD We are pleased to publish the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) quarterly report on Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). This is our eighth quarterly report on the overseas contingency operation (OCO), discharging our individual and collective agency oversight responsibilities pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978. OIR is dedicated to countering the terrorist threat posed by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in Iraq, Syria, the region, and the broader international community. The U.S. -

The Hugo Valentin Centre

The Hugo Valentin Centre Master Thesis in Holocaust and Genocide Studies Syrian Kurds amid Violence Depictions of Mass Violence against Syrian Kurdistan in Kurdish Media, 2014–2019 Student: Abdulilah Ibrahim Term and year: Spring 2021 Credits: 45 Supervisor: Tomislav Dulić Word count: 28553 Table of Contents List of tables ...................................................................................................................................... 2 List of figures .................................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract............................................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgment ............................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Aims and Research Questions ................................................................................................. 6 Structure of the thesis ................................................................................................................ 7 Research overview ...................................................................................................................... 7 Theory and method...................................................................................................................14 -

The PYD's Precarious Rise in Syria

Flight of Icarus? The PYD’s Precarious Rise in Syria Middle East Report N°151 | 8 May 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. An Opportunity Grasped .................................................................................................. 4 A. The PKK Returns to Syria .......................................................................................... 4 B. An Unspoken Alliance? .............................................................................................. 7 C. Brothers and Rivals .................................................................................................... 10 III. From Fighters to Rulers ................................................................................................... 12 A. The Rojava Project ..................................................................................................... 12 B. In Need of Protection ................................................................................................. 16 IV. Messy Geopolitics ............................................................................................................. 18 A. Turkey and -

Sdf's Arab Majority Rank Turkey As the Biggest

SDF’S ARAB MAJORITY RANK TURKEY AS THE BIGGEST THREAT TO NE SYRIA. Survey Data on America’s Partner Forces Amy Austin Holmes 2 0 1 9 Arab women from Deir Ezzor who joined the SDF after living under the Islamic State Of all the actors in the Syrian conflict, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) are perhaps the most misunderstood party. Five years after the United States decided to partner with the SDF, gaping holes remain in our knowledge about the women and men who defeated the Islamic State (IS). In order to remedy the knowledge gap, I conducted the first field survey of the Syrian Democratic Forces. Through multiple visits to all of the governorates of Northeastern Syria under SDF control, I have generated new and unprecedented data, which can offer policy guidance as the United States must make decisions about how to move forward in the post-caliphate era. There are a number of reasons for the current lack of substantive information on the SDF. First, the SDF has been in a state of constant expansion ever since it was created, pro- gressively recruiting more people and capturing more territory. And, as a non-state actor, the SDF lacks the bureaucracy of national armies. Defeating the Islamic State was their priority, not collecting statistics. The SDF’s low media profile has also played a role. Perhaps wary of their status as militia leaders, high-ranking commanders have been reticent to give interviews. Recently, Gen- eral Mazlum Kobani, the Kurdish commander-in-chief of the SDF, has conducted a few interviews.1 And even less is known about the group’s rank-and-file troops. -

Security Council Distr.: General 7 December 2012

United Nations S/2012/623 Security Council Distr.: General 7 December 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 10 August 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25, 27 and 28 June, 2, 3, 9, 11, 13, 17 and 24 July, and 1, 2, 8 and 10 August 2012, I have the honour to transmit herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria from Tuesday evening, 30 July 2012 until Wednesday evening, 31 July 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-63454 (E) 131212 141212 *1263454* S/2012/623 Annex to the identical letters dated 10 August 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] List of the most serious attacks and violations carried out by armed terrorist groups between 2000 hours on 30 July 2012 and 2000 hours on 31 July 2012 No. Governorate Time Violation/attack 1. Hama 0610 Armed terrorist groups detonated one explosive device in the vicinity of the military petrol station and another near the prison roundabout.