COVID-19 & Counterterrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Are Lowland Areas Along the Caspian, Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman Coasts

1 2 fb Contents Centre for Security, Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR), University of Lahore 3 Country Study of Iran...................................................................................................................4 Geographic Contours ..............................................................................................................4 1. Terrain .......................................................................................................................4 2. Climate ......................................................................................................................4 Historical Perception ...............................................................................................................4 Society ..................................................................................................................................8 1. Demography ..............................................................................................................8 2. Ethnic Groups ............................................................................................................8 3. Languages .................................................................................................................8 4. Social Structure ..........................................................................................................8 5. Religion .....................................................................................................................9 6. Education ..................................................................................................................9 -

Bulletin De Liaison Et D'information

INSTITUT KUDE RPARD IS E Bulletin de liaison et d’information N°364 JUILLET 2015 La publication de ce Bulletin bénéficie de subventions du Ministère français des Affaires étrangères (DGCID) et du Fonds d’action et de soutien pour l’intégration et la lutte contre les discriminations (FASILD) ————— Ce bulletin paraît en français et anglais Prix au numéro : France: 6 € — Etranger : 7,5 € Abonnement annuel (12 numéros) France : 60 € — Etranger : 75 € Périodique mensuel Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Numéro de la Commission Paritaire : 659 13 A.S. ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tél. : 01- 48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01- 48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: [email protected] Bulletin de liaison et d’information de l’Institut kurde de Paris N° 364 juillet 2015 • TURQUIE : VERS LA FIN DU PROCESSUS DU PAIX ? • SYRIE : LES KURDES FONT RECULER LE DAESH • KURDISTAN : POINT SUR LA GUERRE CONTRE LE DAESH • PARIS : MORT DU PEINTRE REMZI • CULTURE : LECTURES POUR L’ÉTÉ TURQUIE : VERS LA FIN DU PROCESSUS DU PAIX ? près le succès électoral GAP) élaboré dans les années Mais le projet du GAP ne datant du HDP, en juin der - 1970, prévoit la construction de pas d’hier, la déclaration du A nier, la situation sécuri - 22 barrages sur les bassins du KCK envisageant de reprendre taire au Kurdistan de Tigre et de l’ Euphrate , afin d’irri - les combats si d’autres barrages Turquie s’est dégradée guer 1,7 million d’hectares de étaient construits, doit plutôt être avec une telle violence que le terres et de fournir 746 MW four - considérée comme une réaction processus de paix initié par nis par 19 centrales hydroélec - de « l’aile dure » du PKK, cher - Öcalan et l’AKP en mars 2013 a triques . -

In-Focus Report on the Main Five Broadcasters

Diversity and equal opportunities in television In-focus report on the main five broadcasters Publication Date: 27 September 2018 Contents Section 1. Introduction 1 2. How diverse is the BBC Public Television Service? 3 3. How diverse is Channel 4? 15 4. How diverse is ITV? 27 5. How diverse is Sky? 39 6. How diverse is Viacom? 51 7. Social Mobility – Recommendations from the Bridge Group 60 Annex A1. Guidance from the Bridge Group 62 Diversity and equal opportunities in television: In-focus report on the main five broadcasters 1. Introduction 1.1 This In-focus report provides more in-depth analysis across each of the main five broadcasters1 and should be read in conjunction with the main report. 1.2 Each section gives an overview of the six protected characteristics for which we collected data, showing profiles for all UK employees across each broadcaster. The top row (purple) shows profiles for gender, racial group and disability, for which data provision was mandatory. The bottom row (blue) shows profiles for age, sexual orientation and religion or belief, for which provision was voluntary. 1.3 Though broadcasters were not required to provide the information requested on a voluntary basis, we consider these to be equally important characteristics that should be monitored to effectively assess how well equal opportunities are being promoted across the industry. We made it clear in our information request that, to provide context and transparency, we would be publishing information on who did and didn’t provide the data requested. 1.4 -

France 2016 International Religious Freedom Report

FRANCE 2016 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution and the law protect the right of individuals to choose, change, and practice their religion. The government investigated and prosecuted numerous crimes and other actions against religious groups, including anti-Semitic and anti- Muslim violence, hate speech, and vandalism. The government continued to enforce laws prohibiting face coverings in public spaces and government buildings and the wearing of “conspicuous” religious symbols at public schools, which included a ban on headscarves and Sikh turbans. The highest administrative court rejected the city of Villeneuve-Loubet’s ban on “clothes demonstrating an obvious religious affiliation worn by swimmers on public beaches.” The ban was directed at full-body swimming suits worn by some Muslim women. ISIS claimed responsibility for a terrorist attack in Nice during the July 14 French independence day celebration that killed 84 people without regard for their religious belief. President Francois Hollande condemned the attack as an act of radical Islamic terrorism. Prime Minister (PM) Manuel Valls cautioned against scapegoating Muslims or Islam for the attack by a radical extremist group. The government extended a state of emergency until July 2017. The government condemned anti- Semitic, anti-Muslim, and anti-Catholic acts and continued efforts to promote interfaith understanding through public awareness campaigns and by encouraging dialogues in schools, among local officials, police, and citizen groups. Jehovah’s Witnesses reported 19 instances in which authorities interfered with public proselytizing by their community. There were continued reports of attacks against Christians, Jews, and Muslims. The government, as well as Muslim and Jewish groups, reported the number of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents decreased by 59 percent and 58 percent respectively from the previous year to 335 anti-Semitic acts and 189 anti-Muslim acts. -

Kurds & the Conflict in Syria

Handout: Kurds & the Conflict in Syria TeachableMoment Handout – page 1 Background The Kurdish fight for a land of their own goes back centuries. The immediate roots of the current conflict date to 2011, when multiple forces in Syria rebelled against the autocratic rule of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. In 2012, Syrian Kurds (the country’s largest ethnic minority) formed their own small self-governed area in northern Syria. In 2014, at the same time as a bloody civil war was raging in Syria, the group ISIS began taking over territory in Iraq and Syria in its attempt to create a fundamentalist Islamic state. The Kurds joined the fight against ISIS and became an essential partner in the U.S.-led coalition battling ISIS. As the Kurds captured ISIS-held territory, suffering enormous casualties, they incorporated the area into their self-rule. Turkey is home to the largest population of Kurds in the world—about 12 million. The Kurdish minority has faced severe repression in Turkey, including the banning of the Kurdish language in speech, publishing, and even song. Even the words “Kurd” and “Kurdish” were banned. The fight for civil and political rights combined with a push for an independent state and erupted into an armed rebellion in the 1980s. The response from the Turkish state and military has been overwhelming and lethal. Tens of thousands of Kurds have been killed in a lopsided on-again off-again war. The self-governed Kurdish areas in Northern Syria came together in 2014 to form an autonomous region with a decentralized democratic government. -

PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 11, Issue 5

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume V, Issue 5 October 2017 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 11, Issue 5 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editors......................................................................................................1 Articles Countering Violent Extremism in Prisons: A Review of Key Recent Research and Critical Research Gaps.........................................................................................................................2 by Andrew Silke and Tinka Veldhuis The New Crusaders: Contemporary Extreme Right Symbolism and Rhetoric..................12 by Ariel Koch Exploring the Continuum of Lethality: Militant Islamists’ Targeting Preferences in Europe....................................................................................................................................24 by Cato Hemmingby Research Notes On and Off the Radar: Tactical and Strategic Responses to Screening Known Potential Terrorist Attackers................................................................................................................41 by Thomas Quiggin Resources Terrorism Bookshelf.............................................................................................................50 Capsule Reviews by Joshua Sinai Bibliography: Terrorist Organizations: Cells, Networks, Affiliations, Splits......................67 Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes Bibliography: Life Cycles of Terrorism..............................................................................107 Compiled and selected by Judith -

Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 414 SEPTEMBER 2019 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019 • TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... • TURKEY: MANY DEMONSTRATIONS AFTER FURTHER DISMISSALS OF HDP MAYORS • ROJAVA: TURKEY CONTINUES ITS THREATS • IRAQ: A CONSTITUTION FOR THE KURDISTAN REGION? • IRAN: HIGHLY CONTESTED, THE REGIME IS AGAIN STEPPING UP ITS REPRESSION TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... he Turkish govern- economist. The vice-president of ten points lower than the previ- ment is increasingly the CHP, Aykut Erdoğdu, ous year, with the disagreement embarrassed by the recalled that the Istanbul rate rising from 38 to 48%. On economic situation. Chamber of Commerce had esti- 16, TurkStat published unem- T The TurkStat Statistical mated annual inflation at ployment figures for June: 13%, Institute reported on 2 22.55%. The figure of the trade up 2.8%, or 4,253,000 unem- September that production in the union Türk-İş is almost identical. ployed. For young people aged previous quarter fell by 1.5% HDP MP Garo Paylan ironically 15 to 24, it is 24.8%, an increase compared to the same period in said: “Mr. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

Methodology Results Introducfion Addifional Informafion Limitafions

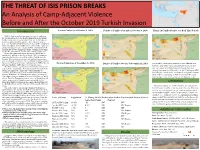

THE THREAT OF ISIS PRISON BREAKS An Analysis of Camp-Adjacent Violence Before and After the October 2019 Turkish Invasion Faction Control (as of October 9, 2019) Density of Conflict (September 2-October 8, 2019) Change in Conflict Density over Both Time Periods Introduction With the Syrian conflict soon posed to enter its ninth year, the war has proven to be the greatest humanitarian and interna- tional security crisis in a generation. However, in the last year — at least in north-east of the country—there had been relative peace. The Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), along with American support, had consolidated its control of the region and all but rooted out the last remnants of ISIS. As of this fall, U.S. and SDF forces were engaged in counter-terrorism raids, ensur- ing that the now-stateless Islamic State remained suppressed. On the other side of the Syrian border sits Turkey, which considers the SDF to be directly tied to the PKK, a terrorist or- ganization that has been in conflict with the Turkish state for decades. This, combined with domestic political pressure to re- settle the millions of Syrian refugees currently residing within its borders, led Turkey to formulate a plan to invade SDF-held terri- Faction Control (as of November 16, 2019) Density of Conflict (October 9-November 16, 2019) records) while investigating potential escapes. Although over tory and establish a “buffer zone” in the border region. half of the total camps changed faction hands during the inva- The United States, eager to protect its wartime partners and to prevent the destabilizing effects of a Turkish incursion in the sion, none ended up in Turkish control. -

Putin's New Russia

PUTIN’S NEW RUSSIA Edited by Jon Hellevig and Alexandre Latsa With an Introduction by Peter Lavelle Contributors: Patrick Armstrong, Mark Chapman, Aleksandr Grishin, Jon Hellevig, Anatoly Karlin, Eric Kraus, Alexandre Latsa, Nils van der Vegte, Craig James Willy Publisher: Kontinent USA September, 2012 First edition published 2012 First edition published 2012 Copyright to Jon Hellevig and Alexander Latsa Publisher: Kontinent USA 1800 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20009 [email protected] www.us-russia.org/kontinent Cover by Alexandra Mozilova on motive of painting by Ilya Komov Printed at Printing house "Citius" ISBN 978-0-9883137-0-5 This is a book authored by independent minded Western observers who have real experience of how Russia has developed after the failed perestroika since Putin first became president in 2000. Common sense warning: The book you are about to read is dangerous. If you are from the English language media sphere, virtually everything you may think you know about contemporary Rus- sia; its political system, leaders, economy, population, so-called opposition, foreign policy and much more is either seriously flawed or just plain wrong. This has not happened by accident. This book explains why. This book is also about gross double standards, hypocrisy, and venal stupidity with western media playing the role of willing accomplice. After reading this interesting tome, you might reconsider everything you “learn” from mainstream media about Russia and the world. Contents PETER LAVELLE ............................................................................................1 -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto