San José Studies, Spring 1983

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain View Whisman School District 750-A San Pierre Way / Mountain View,CA 94043 / 650-526-3500 X 1023

Mountain View Whisman School District 750-A San Pierre Way / Mountain View,CA 94043 / 650-526-3500 x 1023 Meeting of the Board of Trustees February 16, 2017 6:30 PM Strategic Plan Goal Areas Student Achievement: Every student will be prepared for high school and 21st century citizenship. Achievement Gap: Achievement gaps will be eliminated for all student groups in all areas. Inclusive and Supportive Culture: Every student, staff, family, and community member will feel valued and supported while working, learning and partnering with MVWSD. Resource Stewardship: Students, staff, and community members will have access to various resources, such as technology, facilities, furniture, equipment, etc,. in a fiscally responsible manner to fulfill the mission of MVWSD. Human Capital: MVWSD will invest in teachers, leaders, and staff to ensure we are the place talented educators choose to work. Mountain View Whisman School District Education for the World Ahead Board of Trustees - Regular Meeting 750-A San Pierre Way, Mountain View, CA and National Conservation Training Center, 698 Conservation Way, Shepherdstown, West Virginia February 16, 2017 6:30 PM (Live streaming available at www.mvwsd.org) As a courtesy to others, please turn off your cell phone upon entering. Under Approval of Agenda, item order may be changed. All times are approximate. I. CALL TO ORDER A. Roll Call B. Approval of Agenda II. OPPORTUNITY FOR MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC TO ADDRESS THE BOARD CONCERNING ITEMS ON THE CLOSED SESSION AGENDA III. CLOSED SESSION A. Potential Litigation 1. Conference with Legal Counsel - Anticipated Litigation B. Negotiations 1. Conference with Real Property Negotiators Government Code Section 54956.8 Property: 310 Easy Street, Mountain View, CA Agency Negotiators: Dr. -

Reading List - Year 5

Reading List - Year 5 We are often asked to recommend books that are popular with children and have a good literary content. Here are some suggestions but we would welcome your views and any others that you think should be added to the list. Authors A to D Janet & Allen Ahlberg The Bear Nobody Wanted * Go Saddle the Sea Joan Aiken *The Wolves of Willoughby Chase Neil Arksey MacB * Break in the Sun Bernard Ashley * Johnnie’s Blitz Steve Barlow Goodknyght! (with Steve Skidmore) Nina Bawden Granny the Pag * A Thief in the Village James Berry * The Future-Telling Lady Terence Blacker The Transfer * Thief! Marjorie Blackman * A.N.T.LD.O.T.E. Martin Booth War Dog Anthony Browne King Kong * The Ghost behind the Wall Melvin Burgess * The Earth Giant Juliet Sharman Burke Stories From the Stars Sheila Burnford The Incredible Journey * The Eighteenth Emergency * Eighteenth Emergency Betsy Byars * Midnight Fox * The Cartoonist * The Midnight Fox Aidan Chambers Seal Secret PJ Lynch & Hans Christian Andersen The Snow Queen Andrew Clements Frindle * Artemis Fowl Eoin Colfer * Benny and Omar * The Wish List * Under the Hawthorn Tree Marita Conlon-McKenna * Wildflower Girl * King of Shadows * The Boggart Susan Cooper * Over Sea, Under Stone * The Dark is Rising Sequence W J Corbett The song of Pentecost * The Bagthorpe Saga Helen Cresswell * Moondial * New World Gillian Cross *The Demon Headmaster * The Great Elephant Chase * Danny, Champion of the World Roald Dahl * The BFG Lavinia Derwent Sula Anita Desai The Village by the Sea Kate Di Camillo Because -

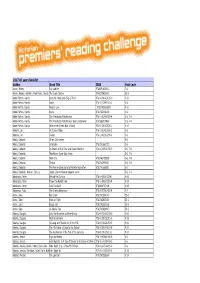

FINAL 2017 All Years Booklist.Xlsx

2017 All years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.)The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker 978-1-86291-920-4 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker Goes Undercover 9781862919488 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight 9781742833491 EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat 9781743620168 EC-2 Acton, Sara As Big As You 9781743629697 -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Carnegie Medal Winning Books

Carnegie Medal Winning Books 2020 Anthony McGowan, Lark, Barrington Stoke 2019 Elizabeth Acevedo, The Poet X, Electric Monkey 2018 Geraldine McCaughrean, Where the World Ends, Usborne 2017 Ruta Sepetys, Salt to the Sea, Puffin 2016 Sarah Crossan, One, Bloomsbury 2015 Tanya Landman, Buffalo Soldier, Walker Books 2014 Kevin Brooks, The Bunker Diary, Puffin Books 2013 Sally Gardner, Maggot Moon, Hot Key Books 2012 Patrick Ness, A Monster Calls, Walker Books 2011 Patrick Ness, Monsters of Men, Walker Books 2010 Neil Gaiman, The Graveyard Book, Bloomsbury 2009 Siobhan Dowd, Bog Child, David Fickling Books 2008 Philip Reeve, Here Lies Arthur, Scholastic 2007 Meg Rosoff, Just in Case, Penguin 2005 Mal Peet, Tamar, Walker Books 2004 Frank Cottrell Boyce, Millions, Macmillan 2003 Jennifer Donnelly, A Gathering Light, Bloomsbury Children’s Books 2002 Sharon Creech, Ruby Holler, Bloomsbury Children’s Books 2001 Terry Pratchett, The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, Doubleday 2000 Beverly Naidoo, The Other Side of Truth, Puffin 1999 Aidan Chambers, Postcards from No Man’s Land, Bodley Head 1998 David Almond, Skellig, Hodder Children’s Books 1997 Tim Bowler, River Boy, OUP 1996 Melvin Burgess, Junk, Anderson Press 1995 Philip Pullman, His Dark Materials: Book 1 Northern Lights, Scholastic 1994 Theresa Breslin, Whispers in the Graveyard, Methuen 1993 Robert Swindells, Stone Cold, H Hamilton 1992 Anne Fine, Flour Babies, H Hamilton 1991 Berlie Doherty, Dear Nobody, H Hamilton 1990 Gillian Cross, Wolf, OUP 1989 Anne Fine, Goggle-eyes, H Hamilton -

![[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7259/pdf-the-myths-and-legends-of-ancient-greece-and-rome-4397259.webp)

[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome

The Myths & Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome E. M. Berens p q xMetaLibriy Copyright c 2009 MetaLibri Text in public domain. Some rights reserved. Please note that although the text of this ebook is in the public domain, this pdf edition is a copyrighted publication. Downloading of this book for private use and official government purposes is permitted and encouraged. Commercial use is protected by international copyright. Reprinting and electronic or other means of reproduction of this ebook or any part thereof requires the authorization of the publisher. Please cite as: Berens, E.M. The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome. (Ed. S.M.Soares). MetaLibri, October 13, 2009, v1.0p. MetaLibri http://metalibri.wikidot.com [email protected] Amsterdam October 13, 2009 Contents List of Figures .................................... viii Preface .......................................... xi Part I. — MYTHS Introduction ....................................... 2 FIRST DYNASTY — ORIGIN OF THE WORLD Uranus and G (Clus and Terra)........................ 5 SECOND DYNASTY Cronus (Saturn).................................... 8 Rhea (Ops)....................................... 11 Division of the World ................................ 12 Theories as to the Origin of Man ......................... 13 THIRD DYNASTY — OLYMPIAN DIVINITIES ZEUS (Jupiter).................................... 17 Hera (Juno)...................................... 27 Pallas-Athene (Minerva).............................. 32 Themis .......................................... 37 Hestia -

TARS Library Catalogue

TARS Library The main purpose of TARS is 'to celebrate and promote the life and woks of Arthur Ransome', and a big part of that is the Society's own Library, with over 1000 books and other material. There are books written about his life, including the time he spent in Russia, reporting about events during the Revolution, and about his early life and how he came to be a writer in the first place. Ransome was the very first winner of the Carnegie Medal awarded by the Library Association (now CILIP) for an outstanding children's book, with Pigeon Post in 1937. The Medal is still presented every year, and we have every single winning book, right up to the present: almost a unique collection. We also have many other children's books, old and new, as well as the Swallows and Amazons series in several different languages. Arthur Ransome had so many interests and he owned books on all of them, and the Library has books on all of those subjects too – sailing, of course, fishing, natural history, crime novels, books by his favourite authors, such as Robert Louis Stevenson (a complete collection of his works) the Lake District, the Norfolk Broads, and even chess! Truly something for everyone, so why not take a look at the complete list here? Then, when you have joined TARS, there are a number of ways you can borrow a book: by e-mailing or writing to the Librarian and having it posted to you – you only need pay the return postage; by visiting the wonderful Moat Brae, home of Peter Pan, in Dumfries and arranging to see the actual Library there; or by attending the no less wonderful Literary Weekends, once every 2 years (next in 2021), where there is always a wide selection of books from the Library to browse. -

Download Bfk 16 September 1982

•vi • m 1 m «M* wtmmmmmmmmmmmammm2 BOOKS FOR KEEPS No. 16 SEPTEMBER 1982 Special Announcement for can be obtained on subscription by sending a cheque or all Books for Keeps readers postal order to the Subscription Secretary, SBA, 1 Effingham Road, Lee, London SE12 8NZ. Tel: 01-852 4953 Annual subscription for six issues: £5.00 UK, £8.00 overseas. Single copies direct from the SBA: 85p UK, £1.35 overseas. Or use the Dial-a-Sub service on 01-852 4953. Editorial correspondence: In the November issue of Extra! can be sold on or given away to Pat Triggs children through your school bookshop, in 36 Ravenswood Road Books for Keeps we are going your library, at your book fair, via your Bristol, Avon, BS6 6BW to publish a special, eight- PTA or in your classroom. It would help us Tel: 0272 49048 enormously if you placed your order (see page, full colour supplement below for details) in advance — to give us Subscriptions and advertising: designed for children between an idea of the likely demand and to enable Richard Hill 7 and 13. We're calling it us to despatch your additional copies (you'll 1 Effingham Road be getting one anyway with your November Lee, London, SE12 8NZ issue of Books for Keeps) as soon as EXTRA! possible in November. Tel: 01-852 4953 If you like the sound of Extra!, use the Our purpose is to provide something that special order form with this September copy does for your children what Books for of Books for Keeps now. -

Cross-Culturalism in Children's Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 465 CS 212 114 AUTHOR Gannon, Susan R., Ed.; Thompson, Ruth Anne, Ed. TITLE Cross-Culturalism in Children's Literature: Selected papers from the 1987 International Conference of the Children's Literature Association (14th, Ottawa, Canada, May 14-17, 1987). INSTITUTION Children's Literature Association. PUB DATE May 87 NOTE 118p.; Publication of this volume was made possible by grants from Dyson College of Pace University and The Growing Child Foundation. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Childrens Literature; *Cross Cultural Studies; *Cultural Differences; *Cultural Pluralism; Elementary Education; Foreign Countries; Literary Criticism; Mythology ABSTRACT This conference proceedings contains a selection of the papers and awards given at a conference held at Carleton University in Canada. After the text of an address by the president of the Children's Literature Association, the following papers are included: (1) "Lone Voices in the Crowd: The Limits of Multiculturalism" (Brian Alderson); (2) "The Elizabeth Cleaver Memorial Lecture" (Irene Aubrey); (3) "Editing Inuit Literature: Leaving the Teeth in the Gently Smiling Jaws" (Robin McGrath); (4) "Cross-Culturalism and Inter-Generational Communication in Children's Literaturq" (Peter Hunt);(5) "Catechisms: Whatsoever a Christian Child Ought to Know" (Patricia Demers); (6) "The Queer, the Strange, and the Curious in 'St. Nicholas': Cross Culturalism in the Nineteenth Century" (Greta Little); (7) "The Clash between Cultural Values: Adult versus Youth on the Battlefield of Poverty" (Diana Chlebek); (8) "Fanny Fern and the Culture of Poverty" (Anne Scott MacLeod); (9) "Crossing and Double Crossing Cultural Barriers in Kipling's 'Kim'" (Judith A. -

The Greek Myths 1955, Revised 1960

Robert Graves – The Greek Myths 1955, revised 1960 Robert Graves was born in 1895 at Wimbledon, son of Alfred Perceval Graves, the Irish writer, and Amalia von Ranke. He went from school to the First World War, where he became a captain in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. His principal calling is poetry, and his Selected Poems have been published in the Penguin Poets. Apart from a year as Professor of English Literature at Cairo University in 1926 he has since earned his living by writing, mostly historical novels which include: I, Claudius; Claudius the God; Sergeant Lamb of the Ninth; Count Belisarius; Wife to Mr Milton (all published as Penguins); Proceed, Sergeant Lamb; The Golden Fleece; They Hanged My Saintly Billy; and The Isles of Unwisdom. He wrote his autobiography, Goodbye to All That (a Penguin Modem Classic), in 1929. His two most discussed non-fiction books are The White Goddess, which presents a new view of the poetic impulse, and The Nazarene Gospel Restored (with Joshua Podro), a re-examination of primitive Christianity. He has translated Apuleius, Lucan, and Svetonius for the Penguin Classics. He was elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 1962. Contents Foreword Introduction I. The Pelasgian Creation Myth 2. The Homeric And Orphic Creation Myths 3. The Olympian Creation Myth 4. Two Philosophical Creation Myths 5. The Five Ages Of Man 6. The Castration Of Uranus 7. The Dethronement Of Cronus 8. The Birth Of Athene 9. Zeus And Metis 10. The Fates 11. The Birth Of Aphrodite 12. Hera And Her Children 13. Zeus And Hera 14. -

The Flood Story, Greek Style

The Flood Story, Greek Style Version One: One of the Greek versions can be found in the book called The Library, attributed to Apollodorus of Alexandria, a second-century BCE author. Section 1.7.2 is offered here in a translation by James Frazer. And Prometheus had a son Deucalion. He reigning in the regions about Phthia, married Pyrrha, the daughter of Epimetheus and Pandora, the first woman fashioned by the gods. And when Zeus would destroy the men of the Bronze Age, Deucalion by the advice of Prometheus constructed a chest, and having stored it with provisions he embarked in it with Pyrrha. But Zeus by pouring heavy rain from heaven flooded the greater part of Greece, so that all men were destroyed, except a few who fled to the high mountains in the neighborhood. It was then that the mountains in Thessaly parted, and that all the world outside the Isthmus and Peloponnese was overwhelmed. But Deucalion, floating in the chest over the sea for nine days and as many nights, drifted to Parnassus, and there, when the rain ceased, he landed and sacrificed to Zeus, the god of Escape. And Zeus sent Hermes to him and allowed him to choose what he would, and he chose to get men. And at the bidding of Zeus he took up stones and threw them over his head, and the stones which Deucalion threw became men, and the stones which Pyrrha threw became women. Hence people were called metaphorically people (laos) from laas, "stone". And Deucalion had children by Pyrrha, first Hellen, whose father some say was Zeus, and second Amphictyon, who reigned over Attica after Cranaus; and third a daughter Protogenia, who became the mother of Aethlius by Zeus. -

Suggested Reading

Suggested Reading Adventure Stories Troy Adele Geras Chinese Cinderella Adeline Yen Mah Survival – Alpha Force 1 Chris Ryan Hornblower CS Forester Journey to the River Sea Eva Ibbotson One Thousand-and-One Arabian Nights Geraldine McCaughrean Coram Boy Jamila Gavin Stratford Boys Jan Mark The 39 Steps John Buchan Moonfleet John Meade Faulkner Around the World in 80 Days Jules Verne The God Beneath the Sea Leon Garfield Holes Louis Sachar The Great Pyramid Robbery Margaret Mahy The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Mark Twain Kensuke’s Kingdom Michael Morpurgo Treasure Island Robert Louis Stevenson The Adventures of Robin Hood Roger Lancelyn Green Beowulf, Dragonslayer Rosemary Sutcliff Haroun and the Sea of Stories Salman Rushdie King of Shadows Susan Cooper Stormbreaker Anthony Horowitz Noughts and Crosses Malorie Blackman The General Robert Muchamore Fantasy Stories and Science Fiction The Owl Service Alan Garner The Weirdstone of Brisingamen Alan Garner Shadow of the Minotaur Alan Gibbons Aquila Andrew Norris Dragonquest Anne McCaffrey Witch Child Celia Rees The Doomspell Cliff McNish Skellig David Almond The Secret of Platform 13 Eva Ibbotson Sabriel Garth Nix Harry Potter JK Rowlings The Wolves of Willoughby Chase Joan Aitken The Box of Delights John Masefield The Day of the Triffids John Wyndham The Lord of the Rings JRR Tolkein Children of the Dust Louise Lawrence Hacker Malorie Blackman The Book of Dead Days Marcus Sedgewick The Changeover Margaret Mahy The Neverending Story Michael Ende His Dark Materials Philip Pullman Mortal Engines