Islamic Architecture in the Cape South Africa, 1794-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

An Analysis of Historical Mussel Watch Programme Data from the West

Marine Pollution Bulletin 87 (2014) 374–380 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Baseline An analysis of historical Mussel Watch Programme data from the west coast of the Cape Peninsula, Cape Town ⇑ Conrad Sparks a, , James Odendaal b, Reinette Snyman a a Department of Biodiversity and Conservation, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, PO Box 652, Cape Town 8000, South Africa b Department of Environmental and Occupational Studies, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, PO Box 652, Cape Town, South Africa article info abstract Article history: The concentrations of metals in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (Lamarck, 1819) prevalent along the Available online 12 August 2014 west coast of the Cape Peninsula, Cape Town are presented. The mussels were sampled during the routine ‘‘Mussel Watch Programme’’ (MWP) between 1985 and 2008. Levels of Cu, Cd, Pb, Zn, Hg, Fe and Mn at Keywords: Cape Point, Hout Bay, Sea Point, Milnerton and Bloubergstrand were analysed for autumn and spring and Metals showed consistent similar mean values for the five sites. There was a highly significant temporal (annual Mussels and seasonal) difference between all metals as well as a significant difference in metal concentrations Mytilus galloprovincialis between the five sites. The concentrations of Zn, Fe, Cd and Pb were higher than previous investigations Long term monitoring and possibly indicative of anthropogenic sources of metals. The results provide a strong motivation to Cape Town South Africa increase efforts in marine pollution research in the area. Ó 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

UCT News Issue 10

April 2016 UCT News Issue 10 Join UCT's online community Journeys through academia: In this latest edition of UCT News, we track the unexpected twists and turns taken by UCT staff and students on their journeys to and through higher education. For more stories like these, keep an eye on the UCT website. How can we transform the professoriate? Dean-designate Bongani Mayosi outlines what can be done to grow and fast-track a new cohort of black and women professors in the Faculty of Health Sciences, using his own career path as a case study. Read more ... Activities News Make a name for yourself: Activist-academic: Rashida “History is like a puzzle”: How a university buildings are under Manjoo's journey from clothing master’s student pieced together review, and UCT wants your input factory clerk to UN investigator of the details of UCT's first black violence against women medical doctor How the Drama Department When an inspiring lecturer PhD student and indigenous interprets South Africa through changes your life’s course: language programmer Joan local lenses, using works from Introducing Ingrid Woolard, Byamugisha’s story is a lesson in SA playwrights UCT’s new dean of commerce persistence What's on at UCT? Find out more How toolmaker-turned-teacher Postdoctoral fellow Tana Joseph’s about university concerts, Gideon Nomdo ended up journey to the stars began when seminars, talks and public lectures recruiting young black students she was 11 with a scrapbook of into academia Hubble images Make it here Applications for study at UCT in 2017 are now open. -

The Battle of Blaauwberg

N 1806 ENGLAND AND FRANCE WERE AT Saldanah Bay to occupy the port. WAR. Both had extensive interests in the East, and the DISCOVER Isafety of their trading fleets and overseas possessions 6th January: The British troops landed at Losperd's Bay, was of great importance. At this time the Cape was now Melkbosstrand. An old transport ship was beached to governed by the Batavian Republic (the name by which the act as a breakwater. One of the landing boats capsized in Netherlands was known from 1795 to 1806), an ally of the surf, drowning 36 Highlanders. Janssens did not France. There were fears of an attack by the British because oppose the landing. The Battle of the Cape's strategic position on the sea route Between Europe and the East. 7th January: The remainder of the British troops, armaments, horses and necessary provisions were landed th of 25 December 1805: After being chased by an English and preparations made for the advance to Cape Town. warship a French Privateer ran aground near Cape Point. Janssens moved his troops out of their camp at Rietvlei and I The French captain brought news to Lieutenant-General J by afternoon had taken up position at Bloubergsvlei farm, Blaauwberg W Janssens, Governor of the Cape, of a strong British fleet on the plains east of Blouberg Hill. His forces bestraddled on route to the Cape. the wagon trail to Cape Town which the advancing British troops would have to~use. British warships started 1" January: A Proclamation was issued for a general call- bombardment of the camp at Rietvlei not knowing that the up of all able-bodied men to defend the Cape. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, and EMPIRE: a PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, AND EMPIRE: A PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R. Stromberg* As we approach the centennial of the Second Anglo–Boer War (Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, or “Second War for Freedom”), reassessment of the South African experience seems in order. Whether the recent surrender by Afrikaner political leaders of their “central theme” and the dismantling of their grandiose Apartheid state will lead to heaven on earth (as some of the Soweto “comrades” expected), or even to a merely tolerable multiracial polity, remains in doubt. Historians have tended to look for the origins of South Africa’s “very strange society” in the interaction of various peoples and political forces on a rapidly changing frontier, especially in the 19th century. APPROACHES TO SOUTH AFRICAN FRONTIER HISTORY At least two major schools of interpretation developed around these issues. The first, Cape Liberals, viewed the frontier Boers largely as rustic ruffians who abused the natives and disrupted or- derly economic progress only to be restrained, at last, by humani- tarian and legalistic British paternalists. Afrikaner excesses, therefore, were the proximate cause and justification of the Boer War and the consolidation of British power over a united South Africa. The “imperial factor” on this view was liberal and pro- gressive in intent if not in outcome. The opposing school were essentially Afrikaner nationalists who viewed the Boers as a uniquely religious people thrust into a dangerous environment where they necessarily resorted to force to overcome hostile African tribes and periodic British harassment. The two traditions largely agreed on the centrality of the frontier, but differed radically on the villains and heroes.1 Beginning in the 1960s and ’70s, a third position was heard, that of younger “South Africanists” driven to distraction (and some *Joseph R. -

Promerops 290.Cdr

PO BOX 2113 CLAREINCH 7740 Website : www.capebirdclub.org.za TEL: 021 559 0726 E-mail : [email protected] THE CAPE BIRD CLUB IS THE WESTERN CAPE BRANCH OF BIRDLIFE SOUTH AFRICA Members requiring information should NOTICE TO note the following telephone numbers : CONTRIBUTORS Hon. President Peter Steyn 021 674 3332 Promerops, the magazine of the Cape Bird Club, is published four times a COMMITTEE MEMBERS: year. It is meant to be by all the Chairman Vernon Head 076 569 1389 members, for all the members. So it Vice-Chairman, Club is YOUR magazine to use. Many Meetings, Junior Club Heather Howell 021 788 1574 members submitted interesting items Treasurer Julian Hare 021 686 8437 for this issue ofPromerops and the Hon. Secretary Helen Fenwick 082 705 1536 editors convey their sincere thanks to Conservation Dave Whitelaw 021 671 3714 all concerned. Fundraising, Functions Anne Gray 021 713 1231 Courses Priscilla Beeton 021 789 0382 Contributions are invited from Camps Charles Saunders 021 797 5710 members in English or Afrikaans on birdwatching, bird sightings, bird New Member Mike Saunders 021 783 5230 observations, news, views, projects, New Member Mervyn Wetmore 021 683 1809 etc., particularly in the southwestern Cape. The abbreviations to use are: OTHER OFFICE BEARERS: Roberts’ Birds of Southern Africa (2005) Information Sylvia Ledgard 021 559 0726 - Roberts’ 7 Membership Secretary Joan Ackroyd 021 530 4435 Promerops Otto Schmidt 021 674 2381 Atlas of the Birds of the Promerops, CBC e-mail Jo Hobbs 021 981 1275 Southwestern Cape (Hockey et al. 1989) - SW Cape Bird Atlas. -

The Ultimate Digital Nomad Guide

THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL NOMAD GUIDE CAPE TOWN 2020 CAPE TOWN - NEW DIGITAL NOMAD HOTSPOT Cape Town has become an attractive destination for digital nomads, looking to venture to an African city and explore the local cultures and diverse wildlife. Cape Town has also become known as Africa’s largest tech hub and is bustling with young startups and small businesses. Cape Town is definitely South Africa’s trendiest city with hipster bars and restaurants along Bree street, exclusive beach strips with five star cuisine and rolling vineyards and wine farms. But is Cape Town a good city for digital nomads. We will dive into this and look at accommodation, co-working spaces, internet connectivity,safety and more. Let's jump into a guide to living and working as a digital nomad in Cape Town, written by digital nomads, from Cape Town. VISA There are 48 countries that do not need a visa to enter South Africa and are abe to stay in SA as a visitor for 90 days. See whether your country makes this list here. The next group of countries are allowed in for 30 days visa-free. Check here to see if your country is on this list. If your country does not fall within these two categories, you will need to apply for a visa. If you can enter on a 90 day visa you can extend it for another 90 days allowing you to stay in South Africa for a total of 6 months. You will need to do this 60 days prior to your visa end date. -

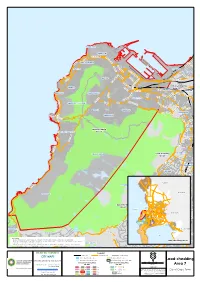

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Forced Removal of Population the Apartheid Regime Has Sought to Enforce Strict Territorial Segregation of the Different ‘Population Groups’

residence, commercial activities and industry for members of the White, Coloured and Asian groups (each in separate zones). Based on these group areas are segregated local government structures, and a segregated tricameral parliament with separate White, Coloured and Indian chambers, designed to preserve white political power while extending limited participation in central government to small sections of the Indian and Coloured communities. The majority of the population in South Africa is united in rejecting the segregated political structures of apartheid. Forced Removal of Population The apartheid regime has sought to enforce strict territorial segregation of the different ‘population groups’. People are forcibly evicted from their homes if they are in a zone which the government has asigned to another group. The government speaks, not of forced removal or eviction, but of Relocation and Resettlement. The evictions take place in many different kinds of areas and under different laws. In rural areas people are moved on a number of different pretexts. The places in which they live may be designated Black Spots — these are areas of land occupied and owned by Africans which the government has designated for another group, usually white. The occupiers are moved to a bantustan. Others are moved in the course of Consolidation of the bantustans, as the regime attempts to reduce the number of fragments of land which make up the bantustans. Over a million black tenants have been evicted from white owned farms since the 1960s. Tenants who paid cash rent to the farms were called Squatters, implying they had no right to be on the land. -

Sarda Fears Move from Current Home

Bulletin NEWS Thursday August 28 2014 3 What’s On Sarda fears move from current home History of land claim Hikes In 1902 Dout Sadien bought three portions of land Peninsula Ramblers from the sub-divided Sillery Estate, one of which have a moderate (Erf 2274) was the family’s home and farmland. hike to Elephant's His five sons bought the property from his estate Eye and in 1958, for about R22 000, but the family was forced Constantiaberg on to sell the farm in 1963 under the Group Areas Act. Saturday August 30. From page 1 Sillery Farm was purchased by Jacob Badenhorst for R13 550 in 1963, R8 450 less than the sons paid Contact Elizabeth Asked if other land claims for it five years earlier. The property is now owned Robinson on 021 have been taken to the Supreme by Jazz Spirit 12 (Pty) Ltd. One of Mr Badenhorst’s 782 6999, 079 888 Court of Appeal, Mr Worsnip descendants is a director of the company, which 6073 or liz @robin- said he is not aware of any. planned to develop the land. In March 2013 Mr son.wcape. Since being informed of the Sadien’s descendant, Igshaan Sadien, said he would school.za settled land claim in March 2013, meet the City of Cape Town and the Land Claims On Sunday August Sarda has investigated alternative Commission to address the matter of the riding 31, they are hiking accommodation in the Constan- school. At that time, Fenella Powles, chairperson in the restricted tia Valley – with little success Sarda, Cape Town branch, said.