Protecting Wild Nature on Native Lands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Warriors: from Warclub to Paper

INDIAN WARRIORS: FROM WARCLUB TO PAPER Geraldo Mosimann da Silva e Simone F. de Athayde http://www.socioambiental.org/website/parabolicas/english/backissu/47/articles/pg5.htm On October 31 last, Kaiabi leaders surprised eight fishermen in the Arraias river, in the Northwest part of the Xingu Indigenous Park (PIX), in Mato Grosso. The Indians lost their patience, apprehended the invaders, and took them to the Diauarum Indigenous Station. That was the start of the Fishermen’s War, which entailed political, social and ethnical conquests. It also means the Kaiabi warriors with fishermen massive presence of warriors from the on release day. Northern peoples of the Park, besides Simone F. de Athayde / ISA leaders of Southern ethnicities who live in the South, and linked to the so-called Upper Xingu Cultural Complex. The episode intensified the feeling of identity of 1,000 Kaiabi, Yudja and Suya Indians who live North of the PIX. This ethnical revitalization process is linked to the strengthening of the Xingu Indigenous Land Association (ATIX) as a representative body of the Xingu peoples for interlocution with non-Indians. Created in 1995, ATIX counts on a political council made of members from 12 ethnicities among the 14 existing in the PIX. In the daily conversations which beaconed their negotiations with FUNAI, the Indians debated the Park’s territory management ad nauseam. It was an exercise of warring strength and ethnical price, punctuated by singing and dancing, where body painting, dressing, adornments, headdresses and warclubs were the rule. Women also surprised: normally relegated to political passivity, they participated with vehement manifestations for the defense of the Park limits. -

Mtv and Transatlantic Cold War Music Videos

102 MTV AND TRANSATLANTIC COLD WAR MUSIC VIDEOS WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH INTRODUCTION In 1986 Music Television (MTV) premiered “Peace Sells”, the latest video from American metal band Megadeth. In many ways, “Peace Sells” was a standard pro- motional video, full of lip-synching and head-banging. Yet the “Peace Sells” video had political overtones. It featured footage of protestors and police in riot gear; at one point, the camera draws back to reveal a teenager watching “Peace Sells” on MTV. His father enters the room, grabs the remote and exclaims “What is this garbage you’re watching? I want to watch the news.” He changes the channel to footage of U.S. President Ronald Reagan at the 1986 nuclear arms control summit in Reykjavik, Iceland. The son, perturbed, turns to his father, replies “this is the news,” and lips the channel back. Megadeth’s song accelerates, and the video re- turns to riot footage. The song ends by repeatedly asking, “Peace sells, but who’s buying?” It was a prescient question during a 1980s in which Cold War militarism and the nuclear arms race escalated to dangerous new highs.1 In the 1980s, MTV elevated music videos to a new cultural prominence. Of course, most music videos were not political.2 Yet, as “Peace Sells” suggests, dur- ing the 1980s—the decade of Reagan’s “Star Wars” program, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and a robust nuclear arms race—music videos had the potential to relect political concerns. MTV’s founders, however, were so culturally conserva- tive that many were initially wary of playing African American artists; addition- ally, record labels were hesitant to put their top artists onto this new, risky chan- 1 American President Ronald Reagan had increased peace-time deicit defense spending substantially. -

Prosodic Distinctions Between the Varieties of the Upper Xingu Carib Language: Results of an Acoustic Analysis

AMERINDIA n°35, 2011 Prosodic distinctions between the varieties of the Upper Xingu Carib language: results of an acoustic analysis Glauber Romling da SILVA & Bruna FRANCHETTO UFRJ, CNPq 1. Introduction: the Upper-Xingu Carib language and its varieties The Carib subsystem of Upper Xingu consists of four local groups: the Kuikuro (four villages, with a fifth one being formed), the Matipu and Nahukwá (who live together in three villages), and the Kalapalo (two villages). All these groups speak a language which belongs to one of the two meridional branches of the Carib family (Meira & Franchetto 2005), and which nowadays presents two main varieties: one spoken by the Kuikuro and the younger Matipu generations, and the other spoken by the Kalapalo and the Nahukwá. Franchetto (2001) states that “we could establish a common origin of the Upper-Xingu Carib from which the first big division would have unfolded (Kalapalo/Nahukwá vs. Kuikuro/Matipu).” These two varieties distinguish themselves by lexical as well as rhythmic differences. According to Franchetto (2001: 133), “in the Carib subsystem of the Culuene river, the interplay between socio-political identities of the local groups (ótomo) is based on distinct rhythmic and prosodic structures”. Speakers express themselves metaphorically when talking about their linguistic identities. From a Kuikuro point of view (or 42 AMERINDIA n°35, 2011 from whom is judging the other) we get the assumption of speaking ‘straight’ (titage) as opposed to speaking as the Kalapalo/Nahukwá do, which is ‘in curves, bouncy, wavy’ (tühenkgegiko) or ‘backwards’ (inhukilü) (Franchetto 1986; Fausto, Franchetto & Heckenberger 2008). In any case, the idea of ‘straightness’ as a way of speaking reveals a value judgment with regard to what it is not. -

The Journal of the American Bamboo Society

The Journal of the American Bamboo Society Volume 15 BAMBOO SCIENCE & CULTURE The Journal of the American Bamboo Society is published by the American Bamboo Society Copyright 2001 ISSN 0197– 3789 Bamboo Science and Culture: The Journal of the American Bamboo Society is the continuation of The Journal of the American Bamboo Society President of the Society Board of Directors Susanne Lucas James Baggett Michael Bartholomew Vice President Norman Bezona Gib Cooper Kinder Chambers Gib Cooper Treasurer Gerald Guala Sue Turtle Erika Harris Secretary David King George Shor Ximena Londono Susanne Lucas Membership Gerry Morris Michael Bartholomew George Shor Mary Ann Silverman Membership Information Membership in the American Bamboo Society and one ABS chapter is for the calendar year and includes a subscription to the bimonthly Newsletter and annual Journal. Membership categories with annual fees: Individual (includes the ABS and one local chapter) US$35, National membership only US$30, National membership from outside the U.S.A. (Does not include chapter membership.) US$35 Commercial membership. US$100.00 additional local chapter memberships US$12.50. Send applications to: Michael Bartholomew ABS Membership 750 Krumkill Road Albany, NY 12203-5976 Cover Photo: Ochlandra scriptoria by K.C. Koshy. See the accompanying article in this issue. Bamboo Science and Culture: The Journal of the American Bamboo Society 15(1): 1-7 © Copyright 2001 by the American Bamboo Society Reproductive biology of Ochlandra scriptoria, an endemic reed bamboo of the Western Ghats, India K. C. Koshy and D. Harikumar Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute, Palode, Thiruvananthapuram – 655 562, Kerala, India. -

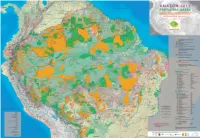

Mapaamazonia2012-Deforestationing

Amazon and human population Bolivia Brasil Colombia Ecuador Guyana Guyane Française Perú Suriname Venezuela total Amazon Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the Amazon total total total total total total total total total total In Amazon the protection of socioenvironmental diversity is being consolidated through the recognition of the territorial rights of indigenous peoples A M A Z O N 2012 Total population and the constitution of a varied set of protected areas. These conservation strategies have been expanding over recent years and today cover a 8,274,325 - 191,480,630 - 42,090,502 - 14,483,499 - 751,000 - 208,171 - 28,220,764 - 492,829 - 27,150,095 - 313,151,815 (nº of inhabitants) surface area of 3,502,750 km2 – 2,144,412 km2 in Indigenous Territories and 1,696,529 km2 in Protected Natural Areas, with an overlap of 336,365 2 Amazon population km between them – which corresponds to 45% of the region. PROTECTED AREAS and INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES 1,233,727 14.9% 23,654,336 12.4% 1,210,549 2.9% 739,814 5.1% 751,000 100.0% 208,171 100.0% 3,675,292 13.0% 492,829 100.0% 1,716,984 6.3% 33,682,702 10.8% (nº of inhabitants) The challenge faced in terms of attaining the objectives of strengthening the cultural and biological diversity of Amazon, represented in indigenous Total area of the country (km2) 1,098,581 - 8,514,876 - 1,141,748 - 249,041 - 214,969 - 86,504 - 1,285,215 - 163,820 - 916,445 - 13,671,199 territories and protected areas, encompasses a variety of aspects. -

Sample Chapter

Chapter Three Money for Nothing Europe had a tightly regulated broadcast spectrum, no cable penetration and satellite dishes were considered a blight on the cultural landscape. There was very little marketing outside the mainstream channels. And then came MTV Europe. It is fair to say that true consumer engagement for youth brands began with MTV. —Matthew Freud, Chairman, freud communications TV Europe was an experiment. No one would know whether M the concept of a single channel broadcasting across Europe was viable until we went out and tried to sell advertising. There were people at Viacom in New York who argued that it would be considerably less expensive to simply direct the American feed to Europe rather than funding a new channel. So I was aware that we had an undetermined but limited timeframe in which to prove we could be profitable. The clock was running. I had no choice but to rely on my time management lesson: Prioritize! My first day on the job had been about securing distribution. My second day was about generating revenue. That second morning, Frank Brown and I made a presentation to Columbia Studios. HBO hadn’t run commercials, so I’d had no experience selling advertising. But as always, when making a sales pitch I tried to be enthusiastic, compelling, and convincing—even if I wasn’t completely certain what I was trying to 67 CH003 29 March 2011; 10:4:23 68 WHATMAKESBUSINESSROCK convince Columbia to do. On occasion, it’s possible to make up in enthusiasm and confidence what you lack in specific knowledge. -

Origem Da Pintura Do Lutador Matipu

GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE MATO GROSSO SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DE MATO GROSSO CARLOS ALBERTO REYES MALDONADO UNEMAT CAMPUS UNIVERSITÁRIO DEP. RENÊ BARBOUR LICENCIATURA INTERCULTURAL INDÍGENA MAIKE MATIPU ORIGEM DA PINTURA DO LUTADOR MATIPU Barra do Bugres 2016 MAIKE MATIPU ORIGEM DA PINTURA DO LUTADOR MATIPU Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado à Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso- UNEMAT, Campus Universitário Dep. Est. Renê Barbour, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de graduado em Línguas, Artes e Literatura. Orientador: Prof.ª Drª. Mônica Cidele da Cruz Barra do Bugres 2016 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA MAIKE MATIPU ORIGEM DA PINTURA DO LUTADOR MATIPU Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado à Banca Avaliadora do Curso de Licenciatura Intercultural – UNEMAT, Campus Universitário Dep. Renê Barbour como requisito para obtenção do título de Licenciado em Línguas, Artes e Literatura. Barra do Bugres, 28 de abril de 2016. BANCA EXAMINADORA _______________________________________________ Prof.ª Drª. Mônica Cidele da Cruz Professora Orientadora _______________________________________________ Prof. Esp. Aigi Nafukuá Professor Avaliador _______________________________________________ Prof. Me. Isaías Munis Batista Professor Avaliador Barra do Bugres 2016 DEDICATÓRIA Dedico este trabalho para minha esposa Soko Kujahi Agika Kuikuro, aos meus filhos, às famílias e filhos da comunidade. Através do conhecimento do meu povo Matipu, consegui realizar o trabalho e fortalecer a cultura para futuras gerações. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço aos dois anciões narradores da história do passado. Principalmente agradeço ao meu pai Yamatuá Matipu, reconhecido como grande flautista e cantor. Agradeço, ainda, Manufá Matipu, que me auxiliou durante a pesquisa sobre o conhecimento dos antepassados. Agradeço a toda minha família que fez o trabalho comigo, e também agradeço muita minha esposa Soko Kujahi Agika Kuikuro, meus filhos Amatuá Matheus Matipu, Kaintehi Marquinho Matipu, Tahugaki Parisi Matipu e Ariati Maiate Rebeca Matipu. -

Af-Energy-Exclusion-Amazon-11-05

Executive Coordinator at Idec Editing Teresa Liporace Clara Barufi Joint Coordinator of the Xingu Graphic design Project at ISA Coletivo Piu (@coletivopiu) Paulo Junqueira Support Coordinator of the Energy and Charles Stewart Mott Sustainability Program at Idec Foundation Clauber Barão Leite Partnership Technical production Instituto Socioambiental – ISA Camila Cardoso socioambiental.org Clauber Barão Leite Published by Marcelo Silva Martins Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa Mayara Mayumi Tamura do Consumidor – Idec Munir Younes Soares idec.org.br Priscila Morgon Arruda São Paulo, May 2021 Index 04 Presentation 06 Executive summary 08 1. Introduction: Legal Amazon 12 2. Covid-19 pandemic impacts in the region 17 3. Energy aspects of the Legal Amazon 19 3.1 The Amazon Isolated Systems 21 3.2 The electricity access exclusion and the Amazon peoples’ development challenges 26 4. The Xingu Indigenous Territory Case: An Example of Challenges to be Faced 30 4.1 Xingu Solar Project 36 5. Idec and ISA recommendations 40 6. References Presentation he Brazilian Institute to clean and sustainable energy, for Consumer in the scope of the public policy T Defense (Instituto aim to universalize access to Brasileiro de Defesa do modern energy services. – Idec) and the Consumidor The Covid-19 pandemic has put Socio-environmental Institute in relief how the lack of electric (Instituto Socioambiental – ISA) energy access weakens the are members of the Energy conditions of life mainly among and Communities Network the Indigenous populations. The (Rede Energia e Comunidades), service availability in the region formed by a group of represents not only a quality of organizations that develop life improvement alternative, but model clean energy projects also the minimal conditions to with and for the sustainable improve community resilience in development of traditional and the matter of health. -

Trade Mark Inter-Partes Decision O/140/07

O-140-07 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF TRADE MARK APPLICATION NO. 2359948 IN THE NAME OF FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD LTD TO REGISTER THE TRADE MARK FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD IN CLASSES 9, 16, 25, AND 41 AND IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER NO. 93033 IN THE NAME OF PETER GILL, MARK O’TOOLE, PAUL RUTHERFORD AND BRIAN NASH Trade Marks Act 1994 IN THE MATTER OF trade mark application No. 2359948 in the name of Frankie Goes to Hollywood Ltd to register the trade mark Frankie Goes To Hollywood in Classes 9, 16, 25, and 41 And IN THE MATTER OF opposition thereto under no. 93033 in the name of Peter Gill, Mark O’Toole, Paul Rutherford and Brian Nash BACKGROUND 1. On 2 April 2004, Frankie Goes to Hollywood Ltd made an application to register the trade mark FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD in Classes 9, 16, 25 and 41 in relation to the following specifications of goods and services: Class 09 Apparatus for recording, transmission or reproduction of sound or images; sound, video and/or data recording and reproducing apparatus; magnetic data carriers; electronically, magnetically or optically recorded data, sound and/or video; electrical and electronic magnetic and/or optical recording apparatus and instruments; recording discs; video tapes; audio tapes; CDs, CD-ROMs; DVDs; computer software; software downloadable from the Internet; digital music; telecommunications apparatus; mouse mats; mobile phone accessories; disc drives; sunglasses; cases for sunglasses; parts and fittings for all the aforesaid goods. Class 16 Paper, cardboard and goods made from these materials; printed matter; printed publications; periodicals; books; magazines; newspapers; newsletters; stationery; coasters; parts and fittings for all the aforesaid goods. -

Aweti (Brazil) - Language Contexts

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 19. Editor: Peter K. Austin Aweti (Brazil) - Language Contexts SEBASTIAN DRUDE Cite this article: Drude, Sebastian. 2020. Aweti (Brazil) - Language Contexts. Language Documentation and Description 19, 45-65. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/208 This electronic version first published: December 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Awetí (Brazil) – Language Contexts Sebastian Drude Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Language Name: Awetí Dialects: None Classification: Tupian, Mawetí-Guaraní branch ISO 639-3 Code: awe Glottolog Code: awet1244 Population: approximately 225 Location: 12°20' S, 53°22' W Upper Xingu, Mato Grosso, Brazil Vitality rating: Endangered / Vigorous (EGIDS 6a) Summary After a catastrophic reduction to only 23 individuals in 1953, today about 225 Awetí (in Awetí: Awytyza) live in now 5 villages the Xingu park in Brazil, where 10 ethnic groups speaking 6 languages live together for centuries. The Awetí speak a Tupian language closely related to the Tupí-Guaraní branch; many also know Kamayurá and increasingly Portuguese, as contact with the Bra-zilian society is growing more intense. -

Tribal Perspectives Teacher Guide

Teacher Guide for 7th – 12th Grades for use with the educational DVD Tribal Perspectives on American History in the Northwest First Edition The Regional Learning Project collaborates with tribal educators to produce top quality, primary resource materials about Native Americans and regional history. Teacher Guide prepared by Bob Boyer, Shana Brown, Kim Lugthart, Elizabeth Sperry, and Sally Thompson © 2008 Regional Learning Project, The University of Montana, Center for Continuing Education Regional Learning Project at the University of Montana–Missoula grants teachers permission to photocopy the activity pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For more information regarding permission, write to Regional Learning Project, UM Continuing Education, Missoula, MT 59812. Acknowledgements Regional Learning Project extends grateful acknowledgement to the tribal representatives contributing to this project. The following is a list of those appearing in the DVD Tribal Perspectives on American History in the Northwest, from interviews conducted by Sally Thompson, Ph.D. Lewis Malatare (Yakama) Lee Bourgeau (Nez Perce) Allen Pinkham (Nez Perce) Julie Cajune (Salish) Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco) Maria Pascua (Makah) Armand Minthorn (Cayuse–Nez Perce) Cecelia Bearchum (Walla Walla–Yakama) Vernon Finley -

Aweti in Relation with Kamayurá: the Two Tupian Languages of the Upper

O presente arquivo está disponível em http://etnolinguistica.org/xingu Alto Xingu UMA SOCIEDADE MULTILÍNGUE organizadora Bruna Franchetto Rio de Janeiro Museu do Índio - Funai 2011 COORDENAÇÃO EDITORIAL , EDIÇÃO E DIAGRAMAÇÃO André Aranha REVISÃO Bruna Franchetto CAPA Yan Molinos IMAGEM DA CAPA Desenho tradicional kuikuro Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) Alto Xingu : uma sociedade multilíngue / organizadora Bruna Franchetto. -- Rio de Janeiro : Museu do Indio - FUNAI, 2011. Vários autores. ISBN 978-85-85986-34-6 1. Etnologia 2. Povos indígenas - Alto Xingu 3. Sociolinguística I. Franchetto, Bruna. 11-02880 CDD-306.44 Índices para catálogo sistemático: 1. Línguas alto-xinguanas : Sociolinguística 306.44 EDIÇÃO DIGITAL DISPON Í VEL EM www.ppgasmuseu.etc.br/publicacoes/altoxingu.html MUSEU DO ÍNDIO - FUNAI PROGRAMA DE PÓS -GRADUAÇÃO EM ANTROPOLOGIA SOCIAL DO MUSEU NACIONAL UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO SEBAST I AN DRUDE AWETI IN ReLATION WITH KAMAYURÁ THE TWO TUP I AN LANGUAGES OF THE UPPER X I NGU S EBAST I AN DRUDE Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt/Main Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi INTRODUCT I ON The Aweti and the Kamayurá are the two peoples speaking Tupian languages within the Upper Xingu system in focus in this volume. This article explores the relationship between the two groups and their languages at various levels, as far as space and our current kno- wledge allow. The global aim is to answer a question that frequently surfaces: how closely related are these two languages? This question has several answers depending on the kind and level of ‘relationship’ between the two languages one wishes to examine.