Maternal Love Shown Through Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories of Ancient Rome Unit 4 Reader Skills Strand Grade 3

Grade 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Skills Strand Ancient Rome Ancient Stories of of Stories Unit 4 Reader 4 Unit Stories of Ancient Rome Unit 4 Reader Skills Strand GraDE 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

Ancient Religions: Public Worship of the Greeks and Romans by E.M

Ancient Religions: Public worship of the Greeks and Romans By E.M. Berens, adapted by Newsela staff on 10.07.16 Word Count 1,250 Level 1190L TOP: The temple and oracle of Apollo, called the Didymaion in Didyma, an ancient Greek sanctuary on the coast of Ionia (now Turkey), Wikimedia Commons. MIDDLE: The copper statue of Zeus of Artemision in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece. BOTTOM: Engraving shows the Oracle of Delphi, bathed in shaft of light atop a pedestal and surrounded by cloaked figures, Delphi, Greece. Getty Images. Temples Long ago, the Greeks had no shrines or sanctuaries for public worship. They performed their devotions beneath the vast and boundless canopy of heaven, in the great temple of nature itself. Believing that their gods lived above in the clouds, worshippers naturally searched for the highest available points to place themselves in the closest communion possible with their gods. Therefore, the summits of high mountains were selected for devotional purposes. The inconvenience of worshipping outdoors gradually suggested the idea of building temples that would offer shelter from bad weather. These first temples were of the most simple form, without decoration. As the Greeks became a wealthy and powerful people, temples were built and adorned with great splendor and magnificence. So massively were they constructed that some of them have withstood the ravages of This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. time. The city of Athens especially contains numerous remains of these buildings of antiquity. These ruins are most valuable since they are sufficiently complete to enable archaeologists to study the plan and character of the original structures. -

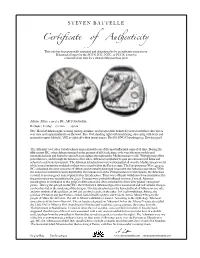

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Magic in Private and Public Lives of the Ancient Romans

COLLECTANEA PHILOLOGICA XXIII, 2020: 53–72 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-0319.23.04 Idaliana KACZOR Uniwersytet Łódzki MAGIC IN PRIVATE AND PUBLIC LIVES OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS The Romans practiced magic in their private and public life. Besides magical practices against the property and lives of people, the Romans also used generally known and used protective and healing magic. Sometimes magical practices were used in official religious ceremonies for the safety of the civil and sacral community of the Romans. Keywords: ancient magic practice, homeopathic magic, black magic, ancient Roman religion, Roman religious festivals MAGIE IM PRIVATEN UND ÖFFENTLICHEN LEBEN DER ALTEN RÖMER Die Römer praktizierten Magie in ihrem privaten und öffentlichen Leben. Neben magische Praktik- en gegen das Eigentum und das Leben von Menschen, verwendeten die Römer auch allgemein bekannte und verwendete Schutz- und Heilmagie. Manchmal wurden magische Praktiken in offiziellen religiösen Zeremonien zur Sicherheit der bürgerlichen und sakralen Gemeinschaft der Römer angewendet. Schlüsselwörter: alte magische Praxis, homöopathische Magie, schwarze Magie, alte römi- sche Religion, Römische religiöse Feste Magic, despite our sustained efforts at defining this term, remains a slippery and obscure concept. It is uncertain how magic has been understood and practised in differ- ent cultural contexts and what the difference is (if any) between magical and religious praxis. Similarly, no satisfactory and all-encompassing definition of ‘magic’ exists. It appears that no singular concept of ‘magic’ has ever existed: instead, this polyvalent notion emerged at the crossroads of local custom, religious praxis, superstition, and politics of the day. Individual scholars of magic, positioning themselves as ostensi- bly objective observers (an etic perspective), mostly defined magic in opposition to religion and overemphasised intercultural parallels over differences1. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

The Agency of Prayers: the Legend of M

The Agency of Prayers: The Legend of M. Furius Camillus in Dionysius of Halicarnassus Beatrice Poletti N THIS PAPER, I examine the ‘curse’ that Camillus casts on his fellow citizens as they ban him from Rome on the accu- sations of mishandling the plunder from Veii and omitting I 1 to fulfill a vow to Apollo. Accounts of this episode (including Livy’s, Plutarch’s, and Appian’s) more or less explicitly recall, in their description of Camillus’ departure, the Homeric prece- dent of Achilles withdrawing from battle after his quarrel with Agamemnon, when he anticipates “longing” for him by the Achaean warriors. Dionysius of Halicarnassus appears to fol- low a different inspiration, in which literary topoi combine with prayer ritualism and popular magic. In his rendering, Camillus pleads to the gods for revenge and entreats them to inflict punishment on the Romans, so that they would be compelled to revoke their sentence. As I show, the terminology used in Dionysius’ reconstruction is reminiscent of formulas in defixi- 1 I.e., the affair of the praeda Veientana. Livy, followed by other sources, relates that before taking Veii Camillus had vowed a tenth of the plunder to Apollo. Because of his mismanagement, the vow could not be immediately fulfilled and, when the pontiffs proposed that the populace should discharge the religious obligation through their share of the plunder, Camillus faced general discontent and eventually a trial (Liv. 5.21.2, 5.23.8–11, 5.25.4–12, 5.32.8–9; cf. Plut. Cam. 7.5–8.2, 11.1–12.2; App. -

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood: A Novel of Ancient Rome Author: Steven Saylor Publisher: St. Martin’s Minotaur Year: 2000 ISBN: 9780312972967 You will be creating a magazine based on this novel. Be creative. Everything about your magazine should be centered around the theme of the novel. Your magazine must contain the following: Cover Table of Contents One: Crossword puzzle OR Word search OR Cryptogram At least 6 (six) news articles which may consist of character interviews, background on the time period, slave/master relationship, Roman law, etc. It is not necessary to interview Saylor. One of the following: horoscopes (relevant to the novel), cartoons (relevant to the novel), recipes (relevant to the novel), want ads (relevant to the novel), general advertisements for products/services (relevant to the novel). There must be no “white/blank” space in the magazine. It must be laid out and must look like a magazine and not just pages stapled together. This must be typed and neatly done. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. Due date: September 1, 2016. Thank you. SUMMER 2016 LATIN II GRADE 10: Amsco Workbook: Work on the review sections after verbs, nouns and adjectives. Complete all mastery exercises on pp. 36-39, 59-61, 64-66, 92-95, 102-104. Please be sure to study all relevant vocab in these mastery exercises. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. -

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica VOL. LI HELSINKI 2017 INDEX Heikki Solin Rolf Westman in Memoriam 9 Ria Berg Toiletries and Taverns. Cosmetic Sets in Small 13 Houses, Hospitia and Lupanaria at Pompeii Maurizio Colombo Il prezzo dell'oro dal 300 al 325/330 41 e ILS 9420 = SupplIt V, 253–255 nr. 3 Lee Fratantuono Pallasne Exurere Classem: Minerva in the Aeneid 63 Janne Ikäheimo Buried Under? Re-examining the Topography 89 Jari-Matti Kuusela & and Geology of the Allia Battlefield Eero Jarva Boris Kayachev Ciris 204: an Emendation 111 Olli Salomies An Inscription from Pheradi Maius in Africa 115 (AE 1927, 28 = ILTun. 25) Umberto Soldovieri Una nuova dedica a Iuppiter da Pompei e l'origine 135 di L. Ninnius Quadratus, tribunus plebis 58 a.C. Divna Soleil Héraclès le premier mélancolique : 147 Origines d'une figure exemplaire Heikki Solin Analecta epigraphica 319–321 167 Holger Thesleff Pivotal Play and Irony in Platonic Dialogues 179 De novis libris iudicia 220 Index librorum in hoc volumine recensorum 277 Libri nobis missi 283 Index scriptorum 286 Arctos 51 (2017) 63–88 PALLASNE EXURERE CLASSEM: MINERVA IN THE AENEID Lee Fratantuono The goddess Minerva is a key figure in the theology of Virgil's Aeneid, though there has been relatively little written to explicate all of the scenes in the epic in which she plays a part or receives a reference.1 The present study seeks to provide a commentary on every mention of Pallas Athena/Minerva in Virgil's poetic corpus, with the intention of illustrating how the goddess plays a crucial role in the unfolding drama of the transition from a Trojan to an Italian identity for the future Rome, and in particular how the Volscian heroine Camilla serves as a mortal incarnation of the Minerva who was a patroness of battles and the military arts. -

Chaucer's Handling of the Proserpina Myth in The

CHAUCER’S HANDLING OF THE PROSERPINA MYTH IN THE CANTERBURY TALES by Ria Stubbs-Trevino A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Literature May 2017 Committee Members: Leah Schwebel, Chair Susan Morrison Victoria Smith COPYRIGHT by Ria Stubbs-Trevino 2017 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Ria Stubbs-Trevino, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my indomitable mother, Amber Stubbs-Aydell, who has always fought for me. If I am ever lost, I know that, inevitably, I can always find my way home to you. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are three groups of people I would like to thank: my thesis committee, my friends, and my family. I would first like to thank my thesis committee: Dr. Schwebel, Dr. Morrison, and Dr. Smith. The lessons these individuals provided me in their classrooms helped shape the philosophical foundation of this study, and their wisdom and guidance throughout this process have proven essential to the completion of this thesis. -

Roman Domestic Religion : a Study of the Roman Lararia

ROMAN DOMESTIC RELIGION : A STUDY OF THE ROMAN LARARIA by David Gerald Orr Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo r the degree of Master of Arts 1969 .':J • APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia Name of Candidate: David Gerald Orr Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis and Abstract Approved: UJ~ ~ J~· Wilhelmina F. {Ashemski Professor History Department Date Approved: '-»( 7 ~ 'ii, Ii (, J ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia David Gerald Orr, Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis directed by: Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, Professor This study summarizes the existing information on the Roman domestic cult and illustrates it by a study of the arch eological evidence. The household shrines (lararia) of Pompeii are discussed in detail. Lararia from other parts of the Roman world are also studied. The domestic worship of the Lares, Vesta, and the Penates, is discussed and their evolution is described. The Lares, protective spirits of the household, were originally rural deities. However, the word Lares was used in many dif ferent connotations apart from domestic religion. Vesta was closely associated with the family hearth and was an ancient agrarian deity. The Penates, whose origins are largely un known, were probably the guardian spirits of the household storeroom. All of the above elements of Roman domestic worship are present in the lararia of Pompeii. The Genius was the living force of a man and was an important element in domestic religion. -

Ancient History, Rome

4rome.qxd 4/14/04 2:33 AM Page 125 Ancient Rome Lesson 11 Rome: Republic to Empire OBJECTIVES Overview This lesson traces the history of Rome from its founding Students will be able to: myths through its kings, the republic, and the end of the republic. First, students hold a discussion on what a dictator • Explain the founding is. Then they read and discuss an article on the beginning of myths of Rome. Rome, the Roman Republic, and its transformation into an • Identify Cincinnatus, empire. Finally, in small groups, students role play members Julius Caesar, Cicero, and of a congressional committee deciding on whether the U.S. Augustus. Constitution should be amended to give the president greater • Describe the government powers in an emergency. of the Roman Republic, the checks on it, and its use of dictators. • Express a reasoned opin- STANDARDS ADDRESSED ion on whether the United States should adopt an California History–Social Science Standard 6.7: Students amendment to grant the analyze the geographic, political, economic, religious, president greater powers and social structures during the development of Rome. in an emergency. (1) Identify the location and describe the rise of the Roman Republic, including the importance of such mythi- cal and historical figures as Aeneas, Romulus and Remus, PREPARATION Cincinnatus, Julius Caesar, and Cicero. (2) Describe the government of the Roman Republic and its significance Handout 11A: Timeline of (e.g., written constitution and tripartite government, Ancient Rome—1 per student checks and balances, civic duty). Handout 11B: Map of the (4) Discuss the influence of Julius Caesar and Augustus in Roman Empire—1 per student Rome’s transition from republic to empire.