THE 3RD CHINA ONSCREEN BIENNIAL Xu Haofeng the Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

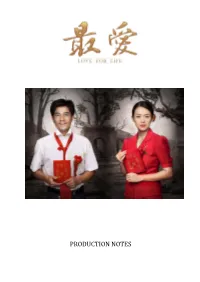

Zhang Ziyi and Aaron Kwok

PRODUCTION NOTES Set in a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, LOVE FOR LIFE is the story of De Yi and Qin Qin, two victims faced with the grim reality of impending death, who unexpectedly fall in love and risk everything to pursue a last chance at happiness before it’s too late. SYNOPSIS In a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, the Zhao’s are a family caught in the middle. Qi Quan is the savvy elder son who first lured neighbors to give blood with promises of fast money while Grandpa, desperate to make amends for the damage caused by his family, turns the local school into a home where he can care for the sick. Among the patients is his second son De Yi, who confronts impending death with anger and recklessness. At the school, De Yi meets the beautiful Qin Qin, the new wife of his cousin and a recent victim of the virus. Emotionally deserted by their respective spouses, De Yi and Qin Qin are drawn to each other by the shared disappointment and fear of their fate. With nothing to look forward to, De Yi capriciously suggests becoming lovers but as they begin their secret affair, they are unprepared for the real love that grows between them. De Yi and Qin Qin’s dream of being together as man and wife, to love each other legitimately and freely, is jeopardized when the villagers discover their adultery. With their time slipping away, they must decide if they will surrender everything to pursue one chance at happiness before it’s too late. -

Jack Johnson Versus Jim Crow Author(S): DEREK H

Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Author(s): DEREK H. ALDERMAN, JOSHUA INWOOD and JAMES A. TYNER Source: Southeastern Geographer , Vol. 58, No. 3 (Fall 2018), pp. 227-249 Published by: University of North Carolina Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of North Carolina Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Southeastern Geographer This content downloaded from 152.33.50.165 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 18:12:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Race, Reputation, and the Politics of Black Villainy: The Fight of the Century DEREK H. ALDERMAN University of Tennessee JOSHUA INWOOD Pennsylvania State University JAMES A. TYNER Kent State University Foundational to Jim Crow era segregation and Fundacional a la segregación Jim Crow y a discrimination in the United States was a “ra- la discriminación en los EE.UU. -

A Brief Analysis of China's Contemporary Swordsmen Film

ISSN 1923-0176 [Print] Studies in Sociology of Science ISSN 1923-0184 [Online] Vol. 5, No. 4, 2014, pp. 140-143 www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/5991 www.cscanada.org A Brief Analysis of China’s Contemporary Swordsmen Film ZHU Taoran[a],* ; LIU Fan[b] [a]Postgraduate, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, effects and packaging have made today’s swordsmen China. films directed by the well-known directors enjoy more [b]Associate Professor, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, China. personalized and unique styles. The concept and type of *Corresponding author. “Swordsmen” begin to be deconstructed and restructured, and the swordsmen films directed in the modern times Received 24 August 2014; accepted 10 November 2014 give us a wide variety of possibilities and ways out. No Published online 26 November 2014 matter what way does the directors use to interpret the swordsmen film in their hearts, it injects passion and Abstract vitality to China’s swordsmen film. “Chivalry, Military force, and Emotion” are not the only symbols of the traditional swordsmen film, and heroes are not omnipotent and perfect persons any more. The current 1. TSUI HARK’S IMAGINARY Chinese swordsmen film could best showcase this point, and is undergoing criticism and deconstruction. We can SWORDSMEN FILM see that a large number of Chinese directors such as Tsui Tsui Hark is a director who advocates whimsy thoughts Hark, Peter Chan, Xu Haofeng , and Wong Kar-Wai began and ridiculous ideas. He is always engaged in studying to re-examine the aesthetics and culture of swordsmen new film technology, indulging in creating new images and film after the wave of “historic costume blockbuster” in new forms of film, and continuing to provide audiences the mainland China. -

Abstract Rereading Female Bodies in Little Snow-White

ABSTRACT REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISIBILITY By Dianne Graf In this thesis, the circumstances and events that motivate the Queen to murder Snow-White are reexamined. Instead of confirming the Queen as wicked, she becomes the protagonist. The Queen’s actions reveal her intent to protect her physical autonomy in a patriarchal controlled society, as well as attempting to prevent patriarchy from using Snow-White as their reproductive property. REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISffiILITY by Dianne Graf A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 December 2008 INTERIM PROVOST AND VICE CHANCELLOR t:::;:;:::.'-H.~"""-"k.. Ad visor t 1.. - )' - i Date Approved Date Approved CCLs~ Member FORMAT APPROVAL 1~-05~ Date Approved ~~ I • ~&1L Member Date Approved _ ......1 .1::>.2,-·_5,",--' ...L.O.LJ?~__ Date Approved To Amanda Dianne Graf, my daughter. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Dr. Loren PQ Baybrook, Dr. Karl Boehler, Dr. Christine Roth, Dr. Alan Lareau, and Amelia Winslow Crane for your interest and support in my quest to explore and challenge the fairy tale world. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER I – BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE LITERARY FAIRY TALE AND THE TRADITIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE FEMALE CHARACTERS………………..………………………. 3 CHAPTER II – THE QUEEN STEP/MOTHER………………………………….. 19 CHAPTER III – THE OLD PEDDLER WOMAN…………..…………………… 34 CHAPTER IV – SNOW-WHITE…………………………………………….…… 41 CHAPTER V – THE QUEEN’S LAST DANCE…………………………....….... 60 CHAPTER VI – CONCLUSION……………………………………………..…… 67 WORKS CONSULTED………..…………………………….………………..…… 70 iv 1 INTRODUCTION In this thesis, the design, framing, and behaviors of female bodies in Little Snow- White, as recorded by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm will be analyzed. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

MIYAKI Yukio (GONG Muduo) 宮木幸雄(龔慕鐸)(B

MIYAKI Yukio (GONG Muduo) 宮木幸雄(龔慕鐸)(b. 1934) Cinematographer Born in Kanagawa Prefecture, Miyaki joined Ari Production in 1952 and once worked as assistant to cinematographer Inoue Kan. He won an award with TV programme Kochira Wa Shakaibu in Japan in 1963. There are many different accounts on how he eventually came to work in Hong Kong. One version has it that he came in 1967 with Japanese director Furukawa Takumi to shoot The Black Falcon (1967) and Kiss and Kill (1967) for Shaw Brothers (Hong Kong) Ltd. Another version says that the connection goes back to 1968 when he helped Chang Cheh film the outdoor scenes of Golden Swallow (1968) and The Flying Dagger (1969) in Japan. Yet another version says that he signed a contract with Shaws as early as 1965. By the mid-1970s, under the Chinese pseudonym Gong Muduo, Miyaki worked as a cinematographer exclusively for Chang Cheh’s films. He took part in over 30 films, including The Singing Thief (1969), Return of the One-armed Swordsman (1969), The Invincible Fist (1969), Dead End (1969), Have Sword, Will Travel (1969), Vengeance! (1970), The Heroic Ones (1970), The New One-Armed Swordsman (1971), The Anonymous Heroes (1971), Duel of Fists (1971), The Deadly Duo (1971), Boxer from Shantung (1972), The Water Margin (1972), Trilogy of Swordsmanship (1972), The Blood Brothers (1973), Heroes Two (1974), Shaolin Martial Arts (1974), Five Shaolin Masters (1974), Disciples of Shaolin (1975), The Fantastic Magic Baby (1975), Marco Polo (1975), 7-Man Army (1976), The Shaolin Avengers (1976), The Brave Archer (1977), The Five Venoms (1978) and Life Gamble (1979). -

Rétrospective Chantal Akerman 31 Janvier – 2 Mars 2018

Rétrospective Chantal Akerman 31 janvier – 2 mars 2018 AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE WALLONIE-BRUXELLES INTERNATIONAL ET LE CONCOURS DU CENTRE WALLONIE BRUXELLES Héritière à la fois de la Nouvelle Vague et du cinéma underground américain, l’œuvre de Chantal Akerman explore avec élégance les notions de frontière et de transmission. Ses films vont de l’essai expérimental (Hotel Monterey), aux récits de la solitude (Jeanne Dielman), en passant par des comédies à l’humour triste (Un divan à New York) et les somptueuses adaptations de classiques littéraires (Proust pour La Captive). CONFÉRENCE et DIALOGUES “CHANTAL AKERMAN : L’ESPACE PENDANT UN CERTAIN TEMPS” PAR JÉRÔME MOMCILOVIC je 01 fév 19h Chantal Akerman a dit souvent son étonnement face à cette formule banale, qui nous vient parfois pour exprimer le plaisir pris un film : ne pas voir le temps passer. De l’appartement du premier film (Saute ma ville, 1968) a celui du dernier (No Home Movie, 2015), des rues traversées par la fiction (Toute une nuit) a celles longées par le documentaire (D’Est), ses films ont suivi une morale rigoureusement inverse : regarder le temps, pour mieux voir l’espace, et nous le faire habiter ainsi en compagnie de tous les fantômes qui le hantent. A la suite de la conférence, à 21h30, projection d’un film choisi par le conférencier : News from Home. Jerome Momcilovic est critique de cinema, responsable des pages cinéma du magazine Chronic’art. Il est l’auteur chez Capricci de Prodiges d’Arnold Schwarzenegger (2016) et, en février 2018, d’un essai sur le cinema de Chantal Akerman Dieu se reposa, mais pas nous. -

Alibaba Pictures , Ruyi Films and Enlight Pictures' Once Upon a Time to Be

IMAX CORPORATION ALIBABA PICTURES , RUYI FILMS AND ENLIGHT PICTURES’ ONCE UPON A TIME TO BE RELEASED IN IMAX® THEATRES ACROSS CHINA SHANGHAI – July 20, 2017 – IMAX Corporation (NYSE:IMAX) and IMAX China Holding Inc. (HKSE: 1970) today announced that Enlight Pictures’, Ruyi Films’ and Alibaba Pictures Group’s much-anticipated fantasy flick, Once Upon a Time, will be digitally re-mastered in the immersive IMAX 3D format and released in approximately 420 IMAX® theatres in China, beginning Aug. 3. Directed by Zhao Xiaoding and Anthony LaMolinara, Once Upon a Time was adapted from the popular fantasy romance novel, illustrating the story of Bai Qian (Liu Yifei) and Ye Hua (Yang Yang). It is produced by well-known filmmaker Zhang Yibai, and stars Liu Yifei, Yang Yang, Luo Jin, Yan Yikuan, Lichun, Gu Xuan and Peng Zisu. Once Upon a Time marks the first Chinese local-language IMAX DMR film in partnership with Alibaba Pictures Group and Ruyi Films, and the second with Enlight Pictures, which released Lost in Hong Kong in 2015. “We are excited to team up with Alibaba Pictures, Ruyi Films and Enlight Pictures, and directors Zhao Xiaoding and Anthony LaMolinara to bring this beloved fantasy novel to life in IMAX,” said Greg Foster, CEO of IMAX Entertainment and Senior Executive Vice President, IMAX Corp. “The film's incredible visual effects showcase The IMAX Experience and create a powerful addition to our summer movie slate.” The IMAX 3D release of Once Upon a Time will be digitally re-mastered into the image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience® with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Re-mastering) technology. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Film and the Chinese Medical Humanities

5 The fever with no name Genre-blending responses to the HIV-tainted blood scandal in 1990s China Marta Hanson Among the many responses to HIV/AIDS in modern China – medical, political, economic, sociological, national, and international – the cultural responses have been considerably powerful. In the past ten years, artists have written novels, produced documentaries, and even made a major feature-length film in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China.1 One of the best-known critical novelists in China today, Yan Lianke 阎连科 (b. 1958), wrote the novel Dream of Ding Village (丁庄梦, copyright 2005; Hong Kong 2006; English translation 2009) as a scath- ing critique of how the Chinese government both contributed to and poorly han- dled the HIV/AIDS crisis in his native Henan province. He interviewed survivors, physicians, and even blood merchants who experienced first-hand the HIV/AIDS ‘tainted blood’ scandal in rural Henan of the 1990s giving the novel authenticity, depth, and heft. Although Yan chose a child-ghost narrator, the Dream is clearly a realistic novel. After signing a contract with Shanghai Arts Press he promised to donate 50,000 yuan of royalties to Xinzhuang village where he researched the AIDS epidemic in rural Henan, further blurring the fiction-reality line. The Chi- nese government censors responded by banning the Dream in Mainland China (Wang 2014: 151). Even before director Gu Changwei 顾长卫 (b. 1957) began making a feature film based on Yan’s banned book, he and his wife Jiang Wenli 蒋雯丽 (b. 1969) sought to work with ordinary people living with HIV/AIDS as part of the process of making the film. -

Lamka Shaolin Disciple's Union Www

Lamka Shaolin Disciple's Union Who's Shifu Zhao Hui? Please try to understand that this is not a school or ordinary Kung Fu school, it is a place of Self- Realization training, Serenity, Insight Reflexion, so processes are not the same with other martial arts training center. Shifu Zhao Hui @ Shifu Khup Naulak, in short, secret disciples of 3 Shaolin Monks, learnt Shaolin Kung Fu at the age of 6 continuously for a period of 9 Years. Now, he's an instructor of Shaolin Kung Fu, Wing Chun, Kick Boxing, Muay Thai, Jeet Kune Do, Krav Maga, MMA (Mixed Martial Arts) or Ground Combats, Bando-Banshay [Burmese Martial Art], Taekwondo, Tai Chi and Qi Gong, Fitness Training and training involves in social and securities hand to hand and armed against unarmed, armed against armed all over the world and already train many special forces which can't be disclosed here due to security issues. Talk to him, he might tell you some of his success and failure stories in his personal and professional life, tournaments, military, self defense training and others if you’re a lucky one. Don't take the chance of falling to the level of half-hearted training; it is better to rise to the level of training that is always deadly serious. Training includes majority of the Chinese weapons like, Nun-Chaku, Gun (Long Stick), Short Stick, Dao like Broad Sword, Butterfly Sword, Flexible Sword, Tai Chi Sword, 3-Section Staff, 9-Section Whip, Animal Styles like Tanglang Quan (Praying Mantis), She Quan (Snake Style), Tiger and Crane Double Form, and etc.