Jack Johnson Versus Jim Crow Author(S): DEREK H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Message

President’s Message his is perhaps the most exciting academic year ever on Hofstra’s campus, as we prepare to host the third and final presidential debate of the 2008 Telection season on October 15, and again present Educate ’08, our unprecedented series of lectures, conferences, exhibitions and events focused on the presidency, history, politics and social issues. For the fall Educate ’08 series, we host nationally known figures such as Robert Rubin and Paul O’Neill, George Stephanopoulos, Dee Dee Myers and Ari Fleischer, Mario Cuomo and the Council on Foreign Relations’ Richard Haass, and many other scholars, journalists and policymakers. The Center for Civic Engagement presents its sixth Day of Dialogue, with nearly 50 sessions on critical issues of the day for Democracy in Performance, a live performance featuring actors portraying historic figures. Many of our academic departments and centers, such as the Peter S. Kalikow Center for the Study of the American Presidency, the National Center for Suburban Studies, and Hofstra Entertainment, will also present events with a presidential theme. The Hofstra Cultural Center’s popular Joseph G. Astman International Concert Series features All American Music, while the Hofstra Cultural Center joins the Hofstra University Museum in presenting a reunion of the directors of Hofstra’s series of renowned presidential conferences for On the Record: A Hofstra Presidential Conference Retrospective. In addition to our exciting political series, the Hofstra Cultural Center and the academic departments continue to present a variety of lectures, concerts, dramatic performances and events that will engage and delight the entire Hofstra and surrounding communities. -

Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, a Public Reaction Study

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study Full Citation: Randy Roberts, “Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study,” Nebraska History 57 (1976): 226-241 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1976 Jack_Johnson.pdf Date: 11/17/2010 Article Summary: Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, played an important role in 20th century America, both as a sports figure and as a pawn in race relations. This article seeks to “correct” his popular image by presenting Omaha’s public response to his public and private life as reflected in the press. Cataloging Information: Names: Eldridge Cleaver, Muhammad Ali, Joe Louise, Adolph Hitler, Franklin D Roosevelt, Budd Schulberg, Jack Johnson, Stanley Ketchel, George Little, James Jeffries, Tex Rickard, John Lardner, William -

Abstract Rereading Female Bodies in Little Snow-White

ABSTRACT REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISIBILITY By Dianne Graf In this thesis, the circumstances and events that motivate the Queen to murder Snow-White are reexamined. Instead of confirming the Queen as wicked, she becomes the protagonist. The Queen’s actions reveal her intent to protect her physical autonomy in a patriarchal controlled society, as well as attempting to prevent patriarchy from using Snow-White as their reproductive property. REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISffiILITY by Dianne Graf A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 December 2008 INTERIM PROVOST AND VICE CHANCELLOR t:::;:;:::.'-H.~"""-"k.. Ad visor t 1.. - )' - i Date Approved Date Approved CCLs~ Member FORMAT APPROVAL 1~-05~ Date Approved ~~ I • ~&1L Member Date Approved _ ......1 .1::>.2,-·_5,",--' ...L.O.LJ?~__ Date Approved To Amanda Dianne Graf, my daughter. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Dr. Loren PQ Baybrook, Dr. Karl Boehler, Dr. Christine Roth, Dr. Alan Lareau, and Amelia Winslow Crane for your interest and support in my quest to explore and challenge the fairy tale world. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER I – BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE LITERARY FAIRY TALE AND THE TRADITIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE FEMALE CHARACTERS………………..………………………. 3 CHAPTER II – THE QUEEN STEP/MOTHER………………………………….. 19 CHAPTER III – THE OLD PEDDLER WOMAN…………..…………………… 34 CHAPTER IV – SNOW-WHITE…………………………………………….…… 41 CHAPTER V – THE QUEEN’S LAST DANCE…………………………....….... 60 CHAPTER VI – CONCLUSION……………………………………………..…… 67 WORKS CONSULTED………..…………………………….………………..…… 70 iv 1 INTRODUCTION In this thesis, the design, framing, and behaviors of female bodies in Little Snow- White, as recorded by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm will be analyzed. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Jack Kerouac's Poetics: Repetition, Language, and Narration in Letters from 1947 to 1956

Department of English Jack Kerouac’s Poetics: Repetition, Language, and Narration in Letters from 1947 to 1956 Nicholas Charles Baldwin Master’s Thesis Transnational Creative Writing Spring, 2019 Supervisor: Adnan Mahmutovic Baldwin 2 Abstract Despite the fame the prolific impressionistic, confessional poet, novelist, literary iconoclast, and pioneer of the Beat Generation, Jack Kerouac, has acquired since the late 1950’s, his written letters are not recognized as works of literature. The aim of this thesis is to examine the different ways in which Kerouac develops and employs the poetics he is most known for in the letters he wrote to friends, family, and publishers before becoming a well-known literary figure. In my analysis of Kerouac’s poetics, I analyze 20 letters from Selected Letters, 1940-1956. These letters were written before the publication of his best-known literary work, On The Road. The thesis attempts to highlight the characteristics of Kerouac’s literary control in his letters and to demonstrate how the examination of these poetics: repetition, language, and narration merits the letters’ treatment as works of artistic literature. Likewise, through the scrutiny of my first novella, “Trails” it then illustrates how the in-depth analysis of Kerouac’s letters improved my personal poetics, which resemble the poetics featured in the letters. Keywords: Poetics; Letter Writing; Impressionism; Confessional; Repetition; Language; Vertical and Circular-Narration; Jack Kerouac; 1947-1956 Baldwin 3 For My Parents From the late 1940’s until the middle 1950’s Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), relatively unknown to the public as an author, was writing novels, poems, and letters extensively. -

Harry Wills and the Image of the Black Boxer from Jack Johnson to Joe Louis

Harry Wills and the Image of the Black Boxer from Jack Johnson to Joe Louis B r i a n D . B u n k 1- Department o f History University o f Massachusetts, Amherst The African-American press created images o f Harry Will: that were intended to restore the image o f the black boxer afterfack fohnson and to use these positive representations as effective tools in the fight against inequality. Newspapers high lighted Wills’s moral character in contrast to Johnsons questionable reputation. Articles, editorials, and cartoons presented Wills as a representative o f all Ameri cans regardless o f race and appealed to notions o f sportsmanship based on equal opportunity in support o f the fighter's efforts to gain a chance at the title. The representations also characterized Wills as a race man whose struggle against boxings color line was connected to the larger challengesfacing all African Ameri cans. The linking o f a sportsfigure to the broader cause o f civil rights would only intensify during the 1930s as figures such as Joe Louis became even more effec tive weapons in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. T h e author is grateful to Jennifer Fronc, John Higginson, and Christopher Rivers for their thoughtful comments on various drafts of this essay. He also wishes to thank Steven A. Riess, Lew Erenberg, and Jerry Gems who contribu:ed to a North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) conference panel where much of this material was first presented. Correspondence to [email protected]. I n W HAT WAS PROBABLY T H E M O ST IMPORTANT mixed race heavyweight bout since Jim Jeffries met Jack Johnson, Luis Firpo and Harry Wills fought on September 11, 1924, at Boyle s Thirty Acres in Jersey City, New Jersey. -

Sunshine State

SUNSHINE STATE A FILM BY JOHN SAYLES A Sony Pictures Classics Release 141 Minutes. Rated PG-13 by the MPAA East Coast East Coast West Coast Distributor Falco Ink. Bazan Entertainment Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Evelyn Santana Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Jackie Bazan Ziggy Kozlowski Marissa Manne 850 Seventh Avenue 110 Thorn Street 8271 Melrose Avenue 550 Madison Avenue Suite 1005 Suite 200 8 th Floor New York, NY 10019 Jersey City, NJ 07307 Los Angeles, CA 9004 New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-445-7100 Tel: 201 656 0529 Tel: 323-655-0593 Tel: 212-833-8833 Fax: 212-445-0623 Fax: 201 653 3197 Fax: 323-655-7302 Fax: 212-833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com CAST MARLY TEMPLE................................................................EDIE FALCO DELIA TEMPLE...................................................................JANE ALEXANDER FURMAN TEMPLE.............................................................RALPH WAITE DESIREE PERRY..................................................................ANGELA BASSETT REGGIE PERRY...................................................................JAMES MCDANIEL EUNICE STOKES.................................................................MARY ALICE DR. LLOYD...........................................................................BILL COBBS EARL PICKNEY...................................................................GORDON CLAPP FRANCINE PICKNEY.........................................................MARY -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

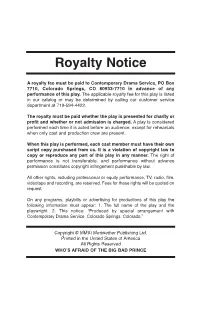

Royalty Notice

Royalty Notice A royalty fee must be paid to Contemporary Drama Service, PO Box 7710, Colorado Springs, CO 80933-7710 in advance of any performance of this play. The applicable royalty fee for this play is listed in our catalog or may be determined by calling our customer service department at 719-594-4422. The royalty must be paid whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is considered performed each time it is acted before an audience, except for rehearsals when only cast and production crew are present. When this play is performed, each cast member must have their own script copy purchased from us. It is a violation of copyright law to copy or reproduce any part of this play in any manner. The right of performance is not transferable, and performance without advance permission constitutes copyright infringement punishable by law. All other rights, including professional or equity performance, TV, radio, film, videotape and recording, are reserved. Fees for these rights will be quoted on request. On any programs, playbills or advertising for productions of this play the following information must appear: 1. The full name of the play and the playwright. 2. This notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Contemporary Drama Service, Colorado Springs, Colorado.” Copyright © MMXI Meriwether Publishing Ltd. Printed in the United States of America All Rights Reserved WHOS AFRAID OF THE BIG BAD PRINCE Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Prince A two-act fairy tale parody/mystery by Craig Sodaro Meriwether Publishing Ltd. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Indian Child Welfare Act: Keeping Our Children Connected to Our Community

FL OJJDP Hearing_Cover.ai 1 4/9/2014 5:08:34 PM AttorneyAttorney General’s Advisory Committee on American Indian/Alask a Nativeative Children Exposed to Violence Briefing Materials Hearing #3: April 16-17, 20142014 - Ft. Lauderdale, Florida Theme: American Indian Children Exposed to Violence in the Community Hyatt Regency Pier Sixty-Six Panorama Ballroom The Tribal Law and Policy Institute www.tlpi.org is providing technical assistance support for the Attorney General’s Task Force on American Indian and Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence including: (1) assisting the Task Force to conduct public hearings and listening sessions, (2) providing primary technical writing services for the final report, and (3) providing all necessary support for the Task Force and the public hearings. Table of Contents Agenda ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Day 1: Wednesday, April 16, 2014 ............................................................................................................ 1 Day 2: Thursday, April 17, 2014 ................................................................................................................ 7 Panel #1: Tribal Leader's Panel: Overview of Violence in Tribal Communities……………………………………..11 Potential Questions for Panelists ............................................................................................................ 15 Written Testimony for Brian Cladoosby ................................................................................................ -

James Earl Jones

James Earl Jones One of the most distinguished living African-American actors, James Earl Jones is as well known for his rich, rumbling baritone as his imposing physical presence. He was born on January 17, 1931, in Arkabutla, Mississippi. His father, Robert Earl Jones, was a prizefighter who turned to acting. His mother, Ruth, was a maid and former schoolteacher. Robert Jones left his family not long after Jones's birth, and the child was adopted and raised on a Michigan farm by his maternal grandparents. Jones developed a strong stutter as a youth and, out of embarrassment, rarely talked until he was 15. A high school English teacher took an interest in him when he learned that Jones wrote poetry. He helped him overcome his stutter and win a scholarship to the University of Michigan, where he went in 1949. Jones started as a premed student and then switched to drama. He graduated magna cum laude in 1953 and served a stint in the army. After his service time, Jones moved to New York City to pursue an acting career and for a time was reunited with his father, another struggling actor. Together they waxed floors for money to live on while auditioning for plays. Jones began getting small parts in Off-Broadway shows but did not land his first role on Broadway until 1957. His career got a big boost when he was invited to join the New York Shakespeare Festival, which performed Shakespeare's plays each summer in Central Park. Jones was impressive in such leading Shakespearean roles as Othello, King Lear, and Oberon, the king of the fairies in A Midsummer Night's Dream.