Jack Kerouac's Poetics: Repetition, Language, and Narration in Letters from 1947 to 1956

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack Johnson Versus Jim Crow Author(S): DEREK H

Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Author(s): DEREK H. ALDERMAN, JOSHUA INWOOD and JAMES A. TYNER Source: Southeastern Geographer , Vol. 58, No. 3 (Fall 2018), pp. 227-249 Published by: University of North Carolina Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of North Carolina Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Southeastern Geographer This content downloaded from 152.33.50.165 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 18:12:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Race, Reputation, and the Politics of Black Villainy: The Fight of the Century DEREK H. ALDERMAN University of Tennessee JOSHUA INWOOD Pennsylvania State University JAMES A. TYNER Kent State University Foundational to Jim Crow era segregation and Fundacional a la segregación Jim Crow y a discrimination in the United States was a “ra- la discriminación en los EE.UU. -

Abstract Rereading Female Bodies in Little Snow-White

ABSTRACT REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISIBILITY By Dianne Graf In this thesis, the circumstances and events that motivate the Queen to murder Snow-White are reexamined. Instead of confirming the Queen as wicked, she becomes the protagonist. The Queen’s actions reveal her intent to protect her physical autonomy in a patriarchal controlled society, as well as attempting to prevent patriarchy from using Snow-White as their reproductive property. REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISffiILITY by Dianne Graf A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 December 2008 INTERIM PROVOST AND VICE CHANCELLOR t:::;:;:::.'-H.~"""-"k.. Ad visor t 1.. - )' - i Date Approved Date Approved CCLs~ Member FORMAT APPROVAL 1~-05~ Date Approved ~~ I • ~&1L Member Date Approved _ ......1 .1::>.2,-·_5,",--' ...L.O.LJ?~__ Date Approved To Amanda Dianne Graf, my daughter. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Dr. Loren PQ Baybrook, Dr. Karl Boehler, Dr. Christine Roth, Dr. Alan Lareau, and Amelia Winslow Crane for your interest and support in my quest to explore and challenge the fairy tale world. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER I – BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE LITERARY FAIRY TALE AND THE TRADITIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE FEMALE CHARACTERS………………..………………………. 3 CHAPTER II – THE QUEEN STEP/MOTHER………………………………….. 19 CHAPTER III – THE OLD PEDDLER WOMAN…………..…………………… 34 CHAPTER IV – SNOW-WHITE…………………………………………….…… 41 CHAPTER V – THE QUEEN’S LAST DANCE…………………………....….... 60 CHAPTER VI – CONCLUSION……………………………………………..…… 67 WORKS CONSULTED………..…………………………….………………..…… 70 iv 1 INTRODUCTION In this thesis, the design, framing, and behaviors of female bodies in Little Snow- White, as recorded by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm will be analyzed. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

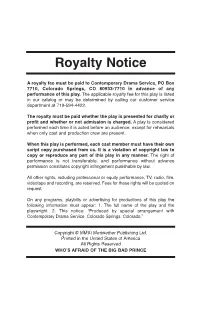

Royalty Notice

Royalty Notice A royalty fee must be paid to Contemporary Drama Service, PO Box 7710, Colorado Springs, CO 80933-7710 in advance of any performance of this play. The applicable royalty fee for this play is listed in our catalog or may be determined by calling our customer service department at 719-594-4422. The royalty must be paid whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is considered performed each time it is acted before an audience, except for rehearsals when only cast and production crew are present. When this play is performed, each cast member must have their own script copy purchased from us. It is a violation of copyright law to copy or reproduce any part of this play in any manner. The right of performance is not transferable, and performance without advance permission constitutes copyright infringement punishable by law. All other rights, including professional or equity performance, TV, radio, film, videotape and recording, are reserved. Fees for these rights will be quoted on request. On any programs, playbills or advertising for productions of this play the following information must appear: 1. The full name of the play and the playwright. 2. This notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Contemporary Drama Service, Colorado Springs, Colorado.” Copyright © MMXI Meriwether Publishing Ltd. Printed in the United States of America All Rights Reserved WHOS AFRAID OF THE BIG BAD PRINCE Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Prince A two-act fairy tale parody/mystery by Craig Sodaro Meriwether Publishing Ltd. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Indian Child Welfare Act: Keeping Our Children Connected to Our Community

FL OJJDP Hearing_Cover.ai 1 4/9/2014 5:08:34 PM AttorneyAttorney General’s Advisory Committee on American Indian/Alask a Nativeative Children Exposed to Violence Briefing Materials Hearing #3: April 16-17, 20142014 - Ft. Lauderdale, Florida Theme: American Indian Children Exposed to Violence in the Community Hyatt Regency Pier Sixty-Six Panorama Ballroom The Tribal Law and Policy Institute www.tlpi.org is providing technical assistance support for the Attorney General’s Task Force on American Indian and Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence including: (1) assisting the Task Force to conduct public hearings and listening sessions, (2) providing primary technical writing services for the final report, and (3) providing all necessary support for the Task Force and the public hearings. Table of Contents Agenda ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Day 1: Wednesday, April 16, 2014 ............................................................................................................ 1 Day 2: Thursday, April 17, 2014 ................................................................................................................ 7 Panel #1: Tribal Leader's Panel: Overview of Violence in Tribal Communities……………………………………..11 Potential Questions for Panelists ............................................................................................................ 15 Written Testimony for Brian Cladoosby ................................................................................................ -

Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2013 Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films Grace DuGar Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation DuGar, Grace, "Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films" (2013). ETD Archive. 387. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/387 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR Bachelor of Arts in Political Science Denison University May 2008 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ENGLISH and the College of Graduate Studies by ____________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Rachel Carnell ______________________________ Department & Date ____________________________________________________________ James Marino ______________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________________ Gary Dyer ______________________________ Department & Date PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR ABSTRACT Disney fairy tale films are not as patriarchal and empowering of men as they have long been assumed to be. Laura Mulvey‘s cinematic theory of the gaze and more recent revisions of her theory inform this analysis of the portrayal of males and females in Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin. -

Maggie's Civics Corner

Maggie’s Civics Corner Lesson 16 Maggie Says... Today’s lesson is about Leaders and Heroes. As a dog, I have many heroes in my life. The crossing guard who makes my walk safe is one of my heroes. Thinking about today’s world, I would put all of the doctors, nurses, and first- responders on my list of heroes. Sticky Situation: I love when someone reads to me. One of my favorite fairy tales is Jack and the Beanstalk. I have listened to that fairy tale many times. Every time I hear it, I wonder if Jack is a hero or a villain. Read the story below. After reading or hearing the story, do you think Jack is a hero or a villain. Be prepared to support your point of view. Jack and the Beanstalk Jack is a very poor young boy who lives in a forest with his mother. Jack and his mother have a cow. It is the cow’s milk that provides them with most of what they have to eat or drink. One day, the cow no longer is able to give milk. Jack’s mom decides that Jack should take the cow to market and sell it in exchange for money and food. As Jack starts off toward the market, he meets a man who offers him beans, magic beans, that the man says will grow very, very tall in only one night. Jack decides to give the man the cow in exchange for the magic beans. When Jack arrives home, he tells his mother what he has done, expecting her to be as excited as he is. -

Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION Media Education Foundation | 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org REEL BAD ARABS HOW HOLLYWOOD VILIFIES A PEOPLE TRANSCRIPT Reel Bad Arabs How Hollywood Vilifies a People Director: SUT JHALLY Producer: JEREMY EARP Post-Production Supervisor: ANDREW KILLOY Editors: SUT JHALLY | ANDREW KILLOY | MARY PATIERNO Additional Editing: JEREMY SMITH Sound Engineering: PETER ACKER, ARMADILLO AUDIO GROUP Media Research and Collection: KENYON KING Subtitling: JASON YOUNG Arabic Translation: HUDA YEHIA, THE TRANSLATION CENTER AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MASS. Graphic Designer: SHANNON MCKENNA DVD Authoring: ANDREW KILLOY | JEREMY SMITH Additonal Motion Graphics: JANET BROCKELHURST Production Assistant: JASON YOUNG Additional Footage Provided By: MARY PATIERNO | THE NEWS MARKET Additional Production Assistance: JANET BROCKELHURST | ANDREW BROOKS | STEVEN COLLETTI STEPHANIE CONVERSE | MARY ALICE CRIM | NAJWA DRURY | ISAAC FLEISHER | REN FULLER- WASSERMAN | AMY HINDLEY | EREZ HOROVITZ | JOHN KEATEN | DANIEL KIM | CAROLYN LITTLE POONAM MALI | ADAM MAROTTE | DAVID MEEK | DAN MONICO | CHRISTINA NEIL | DIMITRI ORAM BRIDGET PALARDY | EVA PICCOZZI | LITA ROBINSON | BRIANNA SPOONER | KRYSTAL TUCKER LEIGH WHITING-JONES FEATURING JACK SHAHEEN MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION 60 Masonic St. | Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org This transcript may be reproduced for educational, non-profit uses only. © 2006 Reel Bad Arabs How Hollywood Vilifies a People JACK SHAHEEN: Arabs are the most maligned group in the history of Hollywood. They’re portrayed basically as sub-humans – ‘Untermenchen’, a term used by Nazis to vilify gypsies and Jews. These images have been with us for more than a century. For thirty years I’ve looked at how we, particular when I say we, image-makers, have projected Arabs on silver screens. -

Arab Stereotypes and American Educators

Arab Stereotypes and American Educators by Marvin Wingfield and Bushra Karaman When American children hear the word "Arab," what is the first thing that often comes to mind? It might well be the Arabian Nights fantasy imagery in the Disney film "Aladdin," a film which has been very popular in theaters and on video and is sometimes shown in school classrooms. Yet Arab Americans have problems with this film. Although in many ways it is charming, artistically impressive and one of the few American films to feature an Arab hero or heroine, a closer look reveals some disturbing features. The film's light-skinned lead characters, Aladdin and Jasmine, have Anglicized features and Anglo American accents. This is in contrast to the other characters who are dark-skinned, swarthy and villainous - cruel palace guards or greedy merchants with "Arabic" accents and grotesque facial features. The film's opening song sets the tone: Oh, I come from a land, From a faraway place Where the caravan camels roam. Where they cut off your ear If they don't like your face. It's barbaric, but hey, it's home. Thus the film immediately characterizes the Arab world as alien, exotic and “other.” Arab Americans see this film as perpetuating the tired stereotype of the Arab world as a place of deserts and camels, of arbitrary cruelty and barbarism. Therefore, Arab Americans raised a cry of protest regarding “Aladdin.” The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) challenged Disney and persuaded the studio to change a phrase in the lyrics for the video version of the film to say: “It's flat and immense, and the heat is intense. -

Jack and the Beanstalk

Jack and the Beanstalk: A Political Reading of an Old, Wise Folktale by Ched Myers (Note : This was a talk given to the “Practicing Resurrection” Conference at Russet House Farm near Cameron, ON in summer 2010) Introduction . In both ancient and modern civilization, the elite control the media. Thus it is the news, the public myths, the histories and the philosophies of the haves that are broadcast and preserved. The perspectives of the have nots are marginal-ized, suppressed and disappeared from history. This means that the points of view of the majority of folk who are not elites, past and present, are difficult to come by, especially for people of relative privilege like us. The poor are not the subjects of our formal education, much less movies, television shows, popular books or political speeches—or if they are, they are relentlessly caricatured, scapegoated or romanticized. However, in the dominant cultures of the North Atlantic, there are two notable exceptions to this rule. The Bible is one; it is the story of desert nomads, freed slaves, highlands hardscrabble farmers and poor urban minorities who are looking and working for God’s justice in a world dominated by empire. Biblical voices and perspectives grate against our modern, rational ears, which is one reason why we should pay close attention to them. The other exception, oddly enough, are old European folk and fairy tales. The versions we all learned at home and school—of e.g. Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, and Snow White—have been largely domesticated and sanitized, of course. But the original tales were earthy and subversive, in which the protagonists are always poor people whose fortunes change through their own cunning and the intervention of magic and mystery.