The Vedas and the Principal Upanishads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art. IX.—On the Interpretation of the Veda

303 ART. IX.—On, the Interpretation of the Veda. BY J. MUIR, Esq. I AM led to make some remarks on the subject of this paper by a passage in Mr. Cowell'3 preface to the fourth volume of the late Professor Wilson's translation of the Big- veda, which appears to me unduly to depreciate the services which have already been rendered by those eminent scholars both in Germany and in England who have begun to apply the scientific processes of modern philology to the explanation of this ancient hymn-collection. Mr. Cowell admits (p. vi.),— " As Vaidik studies progress, and more texts are published and studied, fresh light will be thrown on these records of the ancient world; and we may gradually attain a deeper insight into their meaning than the mediaeval Hindus could possess, just as a modern scholar may understand Homer more thoroughly than the Byzantine scholiasts." But he goes on to say :— "It is easy to depreciate native commentators, but it is not so easy to supersede them; and while I would by no means uphold Sayana as infallible, I confess that, in the present early stage of Vaidik studies in Europe, it seems to me the safer course to follow native tradition rather than to accept too readily the arbitrary con- jectures which continental scholars so often hazard." Without considering it necessary to examine, or defend, all the explanations of particular words proposed by the foreign lexicographers alluded to by Mr. Cowell, I yet venture to think that those scholars have been perfectly justified in com- mencing at once the arduous task of expounding the Veda on the principles of interpretation which they have adopted and enunciated. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

PDF Format of This Book

COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD SWAMI KRISHNANANDA Published by THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India www.sivanandaonline.org, www.dlshq.org First Edition: 2017 [1,000 copies] ©The Divine Life Trust Society EK 56 PRICE: ` 95/- Published by Swami Padmanabhananda for The Divine Life Society, Shivanandanagar, and printed by him at the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy Press, P.O. Shivanandanagar, Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India For online orders and catalogue visit: www.dlsbooks.org puBLishers’ note We are delighted to bring our new publication ‘Commentary on the Mundaka Upanishad’ by Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj. Saunaka, the great householder, questioned Rishi Angiras. Kasmin Bhagavo vijnaate sarvamidam vijnaatam bhavati iti: O Bhagavan, what is that which being known, all this—the entire phenomena, experienced through the mind and the senses—becomes known or really understood? The Mundaka Upanishad presents an elaborate answer to this important philosophical question, and also to all possible questions implied in the one original essential question. Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave a verse-by-verse commentary on this most significant and sacred Upanishad in August 1989. The insightful analysis of each verse in Sri Swamiji Maharaj’s inimitable style makes the book a precious treasure for all spiritual seekers. —THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY 5 TABLE OF Contents Publisher’s Note . 5 CHAPTER 1: Section 1 . 11 Section 2 . 28 CHAPTER 2: Section 1 . 50 Section 2 . 68 CHAPTER 3: Section 1 . 85 Section 2 . 101 7 COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD Chapter 1 SECTION 1 Brahmā devānām prathamaḥ sambabhūva viśvasya kartā bhuvanasya goptā, sa brahma-vidyāṁ sarva-vidyā-pratiṣṭhām arthavāya jyeṣṭha-putrāya prāha; artharvaṇe yām pravadeta brahmātharvā tām purovācāṅgire brahma-vidyām, sa bhāradvājāya satyavāhāya prāha bhāradvājo’ṇgirase parāvarām (1.1.1-2). -

108 Upanishads

108 Upanishads From the Rigveda 36 Dakshinamurti Upanishad From the Atharvaveda 1 Aitareya Upanishad 37 Dhyana-Bindu Upanishad 78 Annapurna Upanishad 2 Aksha-Malika Upanishad - 38 Ekakshara Upanishad 79 Atharvasikha Upanishad about rosary beads 39 Garbha Upanishad 80 Atharvasiras Upanishad 3 Atma-Bodha Upanishad 40 Kaivalya Upanishad 81 Atma Upanishad 4 Bahvricha Upanishad 41 Kalagni-Rudra Upanishad 82 Bhasma-Jabala Upanishad 5 Kaushitaki-Brahmana 42 Kali-Santarana Upanishad 83 Bhavana Upanishad Upanishad 43 Katha Upanishad 84 Brihad-Jabala Upanishad 6 Mudgala Upanishad 44 Katharudra Upanishad 85 Dattatreya Upanishad 7 Nada-Bindu Upanishad 45 Kshurika Upanishad 86 Devi Upanishad 8 Nirvana Upanishad 46 Maha-Narayana (or) Yajniki 87 Ganapati Upanishad 9 Saubhagya-Lakshmi Upanishad Upanishad 88 Garuda Upanishad 10 Tripura Upanishad 47 Pancha-Brahma Upanishad 48 Pranagnihotra Upanishad 89 Gopala-Tapaniya Upanishad From the Shuklapaksha 49 Rudra-Hridaya Upanishad 90 Hayagriva Upanishad Yajurveda 50 Sarasvati-Rahasya Upanishad 91 Krishna Upanishad 51 Sariraka Upanishad 92 Maha-Vakya Upanishad 11 Adhyatma Upanishad 52 Sarva-Sara Upanishad 93 Mandukya Upanishad 12 Advaya-Taraka Upanishad 53 Skanda Upanishad 94 Mundaka Upanishad 13 Bhikshuka Upanishad 54 Suka-Rahasya Upanishad 95 Narada-Parivrajaka 14 Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 55 Svetasvatara Upanishad Upanishad 15 Hamsa Upanishad 56 Taittiriya Upanishad 96 Nrisimha-Tapaniya 16 Isavasya Upanishad 57 Tejo-Bindu Upanishad Upanishad 17 Jabala Upanishad 58 Varaha Upanishad 97 Para-Brahma Upanishad -

The Transformation of the Self in Mahayana Buddhism

The Transformation of the Self in Mahayana Buddhism A Theoretical Study Kurethara S. Bose Religious EXPERIENCE AT the ultimate level, it is often said, leads to a radical transformation of the self. The union with the Supreme Being, Brahman, in the Upanishads, and nirvana in Buddhism correspond to a fundamental and radical change in the way the self apprehends itself and the world. Tao in Taoism, Brahman in the Upanishads, and nir vana in Buddhism embody absolute knowledge, the true form of the self and the world. The realization of Brahman and nirvana is the tran scendence of the false understanding of the self and the world, and the realization of the true nature of the self and the world. Once the self at tains true knowledge it overcomes bondage and suffering, which afflict mundane existence, and achieves total freedom. Self and its existential condition are transformed as the conception of the self and the world are transformed. One of the most distinctive features of man is that he is a conscious being. Thought provides the basic framework by which human beings define and apprehend the world and the nature of the self. The form of thought determines the form of conceptual systems, and the form of conceptual systems shapes the form of individual and social action. Knowledge, founded upon thought, gives form, order and meaning to individual expressions. The nature of the self is defined by the concep tion of the self. For the conception of the self determines its expres sions—expressions which define the self. * A shorter version of this study was presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion at Washington, D.C., November 5-8, 1992. -

Ishavasya Upanishad

DzÉÉuÉÉxrÉÉåmÉÌlÉwÉiÉç ISHAVASYA UPANISHAD The All-Pervading Reality “THE SANDEEPANY EXPERIENCE” Reflections by TEXT SWAMI GURUBHAKTANANDA 19 Sandeepany’s Vedanta Course List of All the Course Texts in Chronological Sequence: Text TITLE OF TEXT Text TITLE OF TEXT No. No. 1 Sadhana Panchakam 24 Hanuman Chalisa 2 Tattwa Bodha 25 Vakya Vritti 3 Atma Bodha 26 Advaita Makaranda 4 Bhaja Govindam 27 Kaivalya Upanishad 5 Manisha Panchakam 28 Bhagavad Geeta (Discourse -- ) 6 Forgive Me 29 Mundaka Upanishad 7 Upadesha Sara 30 Amritabindu Upanishad 8 Prashna Upanishad 31 Mukunda Mala (Bhakti Text) 9 Dhanyashtakam 32 Tapovan Shatkam 10 Bodha Sara 33 The Mahavakyas, Panchadasi 5 11 Viveka Choodamani 34 Aitareya Upanishad 12 Jnana Sara 35 Narada Bhakti Sutras 13 Drig-Drishya Viveka 36 Taittiriya Upanishad 14 “Tat Twam Asi” – Chand Up 6 37 Jivan Sutrani (Tips for Happy Living) 15 Dhyana Swaroopam 38 Kena Upanishad 16 “Bhoomaiva Sukham” Chand Up 7 39 Aparoksha Anubhuti (Meditation) 17 Manah Shodhanam 40 108 Names of Pujya Gurudev 18 “Nataka Deepa” – Panchadasi 10 41 Mandukya Upanishad 19 Ishavasya Upanishad 42 Dakshinamurty Ashtakam 20 Katha Upanishad 43 Shad Darshanaah 21 “Sara Sangrah” – Yoga Vasishtha 44 Brahma Sootras 22 Vedanta Sara 45 Jivanmuktananda Lahari 23 Mahabharata + Geeta Dhyanam 46 Chinmaya Pledge A NOTE ABOUT SANDEEPANY Sandeepany Sadhanalaya is an institution run by the Chinmaya Mission in Powai, Mumbai, teaching a 2-year Vedanta Course. It has a very balanced daily programme of basic Samskrit, Vedic chanting, Vedanta study, Bhagavatam, Ramacharitmanas, Bhajans, meditation, sports and fitness exercises, team-building outings, games and drama, celebration of all Hindu festivals, weekly Gayatri Havan and Guru Paduka Pooja, and Karma Yoga activities. -

1 BLOCK-2 INTRODUCTION the Upanishads Are Hindu Scriptures

BLOCK-2 INTRODUCTION The Upanishads are Hindu scriptures that constitute the core teachings of Vedanta. They do not belong to any particular period of Sanskrit literature: the oldest, such as the Brhadaranyaka and Chandogya Upanishads, date to the late Brahmana period (around the middle of the first millennium BCE), while the latest were composed in the medieval and early modern period. The Upanishads have exerted an important influence on the rest of Indian Philosophy, and were collectively considered one of the 100 most influential books ever written by the British poet Martin Seymour-Smith. The philosopher and commentator Shankara is thought to have composed commentaries on eleven mukhya or principal Upanishads, those that are generally regarded as the oldest, spanning the late Vedic and Mauryan periods. The Muktika Upanishad (predates 1656) contains a list of 108 canonical Upanishads and lists itself as the final one. Although there are a wide variety of philosophical positions propounded in the Upanishads, commentators since Shankara have usually followed him in seeing Advaita as the dominant one. Unit 1 is on “Introduction to the Upanishads.” In this unit, you will become familiar with the general tenor of the Upanishads. You are expected to recognize the differences between the Vedas and the Upanishads not only in content but also in spirit. Secondly, you should be able to notice various philosophical and primitive scientific issues which have found place in the Upanishads. In the end, you should be in a position to understand that philosophy is not merely an intellectual exercise in India, but it is also the guiding factor of human life. -

The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen

The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen. The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and philological papers on a Vedic tradition. Arlo Griffiths; Annette Schmiedchen. 11, Shaker, 2007, Indologica Halensis, 978-3-8322-6255-6. halshs-01929253 HAL Id: halshs-01929253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01929253 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Griffiths, Arlo, and Annette Schmiedchen, eds. 2007. The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition. Indologica Halensis 11. Aachen: Shaker. Contents Arlo Griffiths Prefatory Remarks . III Philipp Kubisch The Metrical and Prosodical Structures of Books I–VII of the Vulgate Atharvavedasam. hita¯ .....................................................1 Alexander Lubotsky PS 8.15. Offense against a Brahmin . 23 Werner Knobl Zwei Studien zum Wortschatz der Paippalada-Sam¯ . hita¯ ..................35 Yasuhiro Tsuchiyama On the meaning of the word r¯as..tr´a: PS 10.4 . 71 Timothy Lubin The N¯ılarudropanis.ad and the Paippal¯adasam. hit¯a: A Critical Edition with Trans- lation of the Upanis.ad and Nar¯ ayan¯ . a’s D¯ıpik¯a ............................81 Arlo Griffiths The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalada¯ School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caran. -

Role of Environment in Vedic Literature

IJA MH International Journal on Arts, Management and Humanities 7(1): 147-150(2018) ISSN No. (Online): 2319–5231 Role of Environment in Vedic Literature Puspa Saikia Assistant Professor, Department of Sanskrit, Ghanakanta Baruah College, Marigaon, Assam, INDIA (Corresponding author: Puspa Saikia) (Received 15 February, 2018, Accepted 27 April, 2018) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: Environment is surrounding the whole gamut of diverse. It includes the land, water, vegetation, air and the whole range of the social order and covers all the disciplines, such as chemistry, biology, ecology, sociology etc. that affect and describe these interactions. Environment would automatically be protected through ethical and spiritual life of the people. Indian life rotates around Indian literature contained in Vedas, Upanishads, Epics and the puranas with dharmashastras in the background. Veda is considered the main source of knowledge. The Vedic literature gives us the genuine principles to adjust with our environment and lead a spiritual life full of bliss. The Veda specially has dealt in detail about various aspects of environment and showed more concern for ecology. Most of the environmental problems of the present day are essentially man made. The role of man is therefore important for shape the environment in perfect harmony. So the proper following of the Vedic techniques, methods and principles and the new knowledge generated through science and technological research should be employed to save the human beings from environmental degradation. I. INTRODUCTION Environment is surrounding the whole range in which we observed, experience and react to event and changes. Environmental Science in its broadest sense in the science of complex interactions that occur among the terrestrial, atmospheric, aquatic, living the anthropological environments and includes all the disciplines such as chemistry, biology, ecology, sociology etc. -

Panduroga: a Medico - Historical Study

Bull.Ind.lnst.Hist.Med. Vol. XXX - 2000 pp 1 to 14 PANDUROGA: A MEDICO - HISTORICAL STUDY P.V.V. PRASAD" ABSTRACT According to Ayurveda the word 'Pandu' denotes Pale or yellowish white colour. Panduroga (anaemia) is a disease in which man becomes Pallor due to deficiency of Rakta dhatu (blood) in the body. Rakta dhatu is mentioned among the Saptadhatus of the body. Historical importance ofPanduroga and a comparative study regarding its Nidana-Samprapti, Lakshanas, Upadravas and Chikitsa etc. as found in Atharvaveda, Mahabharata, Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, Chakradatta and Basava Rajeeyam etc. are being presented in this paper. Introduction: Regarding the aetiology, types, There are seven important constituents symptoms, complications and treatment of viz. Rasa, Rakta, Mamsa, Medo, Asthi, Panduroga a comparative study has been Majja and Shukra in the human body. They done based on Atharvaveda, Mahabharata, are known as "Sapthadhatu" in Ayurveda. Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, Amongst them Rakta (blood) is a very Astanga Hridaya, Astanga Sangraha, important dhatu. Acharya Sushruta has Madhava Nidana, Chakradatta, Bhava mentioned Rakta dhatu as fourth dosha of Prakasa Samhita and Basava Rajeeyam. In the body i.e. in addition to three doshas viz., addition to this, references were also Vata, Pitta and Kapha (Su.Sutra21/3). He collected regarding the usage ofLauha (iron) mentions that, Rakta is the life in living body. and Mandura and their preparations for Therefore it should be protected from all treating this important disease. types of vitiations and Pathogenic factors Atharvaveda : (Su.Sutra 14/44). Panduroga develops due This fourth and last veda of Indian to deficiency of blood in one's body. -

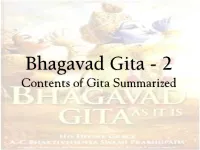

Bhagavad Gita-Chapter 02

Bhagavad Gita - 2 Contents of Gita Summarized Based on the teachings of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada ~Founder Acharya~ International Society for Krishna Consciousness Chapter 2 - Sections Section Verse Description A 2.1 to 2.10 Arjuna's further doubts & his surrender B 2.11 to 2.30 Jnana -- fight! there is no death for the soul C 2.31 to 2.38 Karmakanda -- fight! for gains come from dutifully fighting and losses come from not fighting D 2.39 to 2.53 Buddhi-yoga (Niskama Karma) --fight! but without any reaction E 2.54 to 2.72 Sthita Prajna -- fight! become fixed in krsna consciousness Summary - Section - A Verse 2.1 to 2.10 Arjuna's further doubts & his surrender 1-10 After Arjuna continues to express his doubts about fighting, he surrenders to Krsna for instruction. Text – 1 Seeing Arjuna depressed Lord Krsna thus spoke…. Analogy – Saving Dress of Drowning Man Material Material Compassion Compassion Real Self signs of Self Lamentation Compassion ignorance (Eternal Realization Soul) Tears • Compassion for the dress of a drowning man is senseless (Sudra) • Real Compassion means Compassion for the Eternal Soul, (Self Realization) • Madhusudana : Killer of Demon Madhu. • Lord Krsna is addressed as Madhusudana, expected to kill Arjuna doubts(demons) Chapter 2 discusses : Soul Explained by Self Analytical Lord Realization Study Krsna Material Body Text – 2 Lord Krsna (Sri-Bhagavan) spoke, where from impurities Analogy - Sun come upon you(Arjuna)? Sunshine-Brahman impersonal all- Absolute Brahman pervasive Truth Spirit. (Sun shine) Lord Krsna The Supreme localized aspect, in heart of all Personality of Paramatma Sun Surface living entities. -

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots Buddhism (Buddha) Followed by Hindūism (Kṛṣṇā) The religion of the Vedic period (also known as Vedism or Vedic Brahmanism or, in a context of Indian antiquity, simply Brahmanism[1]) is a historical predecessor of Hinduism.[2] Its liturgy is reflected in the Mantra portion of the four Vedas, which are compiled in Sanskrit. The religious practices centered on a clergy administering rites that often involved sacrifices. This mode of worship is largely unchanged today within Hinduism; however, only a small fraction of conservative Shrautins continue the tradition of oral recitation of hymns learned solely through the oral tradition. Texts dating to the Vedic period, composed in Vedic Sanskrit, are mainly the four Vedic Samhitas, but the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and some of the older Upanishads (Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Chāndogya, Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana) are also placed in this period. The Vedas record the liturgy connected with the rituals and sacrifices performed by the 16 or 17 shrauta priests and the purohitas. According to traditional views, the hymns of the Rigveda and other Vedic hymns were divinely revealed to the rishis, who were considered to be seers or "hearers" (shruti means "what is heard") of the Veda, rather than "authors". In addition the Vedas are said to be "apaurashaya", a Sanskrit word meaning uncreated by man and which further reveals their eternal non-changing status. The mode of worship was worship of the elements like fire and rivers, worship of heroic gods like Indra, chanting of hymns and performance of sacrifices. The priests performed the solemn rituals for the noblemen (Kshsatriya) and some wealthy Vaishyas.