Processes of Pakeha Change in Response To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CULT of RUA During the First Third of The

Allan Hanson CHRISTIAN BRANCHES, MAORI ROOTS: THE CULT OF RUA During the first third of the twentieth century a New Zealand Maori named Rua Kenana, proclaiming himself to be a Messiah and the brother of Jesus, or even Jesus himself, headed a millenarian move- ment that attracted many adherents among Maoris of the Tuhoe and Whakatohea tribes.' The movement included the express intention to eradicate all traces of the old Maori religion. Nevertheless, the cult contained much that derived from indigenous Maori culture. This essay attempts to sort out the Judeo-Christian and Maori sources of Thanks are due to Judith Binney and Peter Webster, without whose careful scholar- ship this paper could not have been written. I am also grateful to Louise Hanson and Fransje Knops for critical comments. I Rua's cult had received very little scholarly attention prior to the appearance of two books, researched independently but both published in 1979. Judith Binney, Gillian Chaplin, and Craig Wallace, Mihaia: The Prophet Rua Kenana and His Community at Maungapohatu (Wellington: Oxford University Press, 1979), tell the story of the move- ment by means of a wealth of contemporaneous photographs conjoined with a carefully researched narrative by Binney. Peter Webster, Rua and the Maori Millennium (Welling- ton: Prince Milburn for Victoria University Press, 1979), perceptively analyzes the cult in terms of a general, cross-cultural theory of millenarian movements. Binney has pub- lished two further essays on Rua's cult, "Maungapohatu Revisited: or, How the Govern- ment Underdeveloped a Maori Community," Journal of the Polynesian Society 92 (1983): 353-92, and "Myth and Explanation in the Ringatu Tradition: Some Aspects of the Leadership of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuku and Rua Kenana Hepetipa," Journal of the Polynesian Society 93 (1984): 345-98. -

Kuia Moko Korero

International Womens Day - 8 March 2019 Government House Auckland by Dr Hiria Hape QSO, PHD, MEd Kuia Tiria Tuhoro !1 Ko Mataatua te waka Ko Maungapohatu te maunga Ko Hamua me Ngati Mura nga hapu Ko Tuhoe te iwi Ko Hiria Hape ahau I am from the Mataatua canoe, My mountain is Maungapohatu Hamua and Ngati Mura are my happé Tuhoe is my iwi My name is Hiria Hape Kia ora huihui tatau katoa Your Excellency The Governor General Dame Patsy Reddy, Tena Koe. Esteemed guests, Ladies and Gentlemen It is an honour and privilege to be here today to speak about the value of women in our communities including whanau (family) hapu (subtribe) and iwi (Tribe). If you went away from today and remembered one part of my speech I would be very happy. Each year around the world, on the 8 March, we celebrate International Womens Day and remember the major contribution women have had in changing the fabric of society, in economic, political and social achievements. In 1893 NZ women led the world as the first country where women won the right to vote and this came about through sheer determination of very strong and courageous women. In May 1893 Meri Mangakahia from Te Rarawa, of Te Tai Tokerau, pushed for Maori women to vote and to stand as candidates for the Maori Parliament. It was not until 1897 when Maori women had the right to vote for members of the Maori Parliament and the House of Representatives. Meri’s actions was an indication of Maori womens political awareness and their ability to arrange and organise themselves. -

The Story of the Treaty Part 1 (Pdf

THE STORY OF THE TREATY Introduction This is the story of our founding document, the Treaty agreement contained within it. At the outset it of Waitangi. It tells of the events leading up to the should be noted that, while the steps leading to the Treaty at a time when Mäori, far outnumbering Treaty are well known and have been thoroughly Päkehä, controlled New Zealand. It describes the studied, historians do differ in what they see as the The Treaty of Waitangi is New Zealand’s founding document. Over 500 Mäori chiefs and essential bargain that was struck between Mäori main developments and trends. Some historians, for representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty in 1840. Like all treaties it is an exchange and the British Crown and what both sides hoped example, emphasise the humanitarian beliefs of the of promises; the promises that were exchanged in 1840 were the basis on which the British to obtain by agreeing to it. However, it does not tell 1830s; others draw attention to the more coercive Crown acquired New Zealand. The Treaty of Waitangi agreed the terms on which New Zealand the full story of what has happened since the signing aspects of British policy or take a middle course would become a British colony. of the Treaty in 1840: of the pain and loss suffered of arguing that while British governments were by Mäori when the Treaty came to be ignored concerned about Mäori, they were equally concerned This is one of a series of booklets on the Treaty of Waitangi which are drawn from the Treaty of by successive settler-dominated governments in about protecting the interests of Britain and British Waitangi Information Programme’s website www.treatyofwaitangi.govt.nz. -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

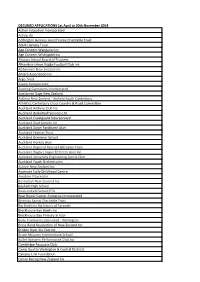

DECLINED APPLICATIONS 1St April to 30Th November 2014 Action

DECLINED APPLICATIONS 1st April to 30th November 2014 Action Education Incorporated Acting Up Addington Harness Hall of Fame Charitable Trust Adult Literacy Trust Age Concern Wanganui Inc Age Concern Whangarei Inc Ahipara School Board of Trustees Alhambra-Union Rugby Football Club Inc Alzheimers New Zealand Inc Antara Association Inc Argo Trust Aspire Incorporated Aspiring Gymsports Incorporated Assistance Dogs New Zealand Asthma New Zealand - Asthma South Canterbury Athletics Canterbury Cross Country & Road Committee Auckland Archery Club Inc Auckland Basketball Services Ltd Auckland Coastguard Incorporated Auckland Deaf Society Inc Auckland Down Syndrome Assn Auckland Festival Trust Auckland Grammar School Auckland Hockey Assn Auckland Regional Rescue Helicopter Trust Auckland Rugby League Referees Assn Inc Auckland University Engineering Sports Club Auckland Youth Orchestra Inc Autism New Zealand Inc Avonside Early Childhood Centre Awatere Playcentre Basketball New Zealand Inc Bayfield High School Beaconsfield School PTA Beat Bowel Cancer Aotearoa Incorporated Bhartiya Samaj Charitable Trust Big Brothers Big Sisters of Taranaki Blockhouse Bay Bowls Inc Blockhouse Bay Primary School Body Positive Incorporated - Wellington Brass Band Association of New Zealand Inc Broken River Ski Club Inc Bruce McLaren Intermediate School Buller Western Performance Club Inc Cambridge Racquets Club Camp Quality Wellington & Central Districts Campus Link Foundation Canoe Racing New Zealand Inc Canterbury Country Cricket Assn Inc Canterbury Hockey Association -

Te Hahi O Te Kohititanga Marama = the Religion of the Reflection of the Moon

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Massey University Lihrary New Zealand & Pacific Ccllecti::" TE HAHI O TE KOHITITANGA MARAMA (The Religion of the Reflection of the Moon) A study of the religion of Te Matenga Tamati A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Religious Studies at Massey University Bronwyn Margaret Elsmore 1983 ii ABSTRACT The Kohiti religion was a vital movement in the Wairoa area for more than thirty years. Its positive view and teaching of inclusiveness and unity brought to the believers a hope, a dream, and a promise. It arose in the last years of the nineteenth century - a time when the Maori was at his lowest ebb numerically and culturally. This, then, was also a time of great spiritual need. Te Matenga Tamati received a revelation to guide his people. As the Christian church did not provide a theological system fully acceptable to the Maori, he formulated a faith that did - being a synthesis of traditional beliefs, Old Testament teachings, and Christian values. Taking the new moon as a symbol, the Kohiti made preparations for a great new age to come. Their efforts to construct a great tabernacle to the Lord is an amazing story, and one which clearly demonstrates the belief of the Maori of this period that they were descendants of the house of Jacob. -

Documenting Maori History

Documenting Maori History: THE ARREST OF TE KOOTI RIKIRANGI TE TURUKI, 1889* TRUTH is ever a casualty of war and of the aftermath of war and so it is of the conflicts between Maori and Pakeha in New Zealand. A bare hun- dred years is too short a time for both peoples, still somewhat uncertainly working out their relationships in New Zealand, to view the nineteenth- century conflicts with much objectivity. Indeed, partly due to the con- fidence and articulateness of the younger generations of Maoris and to their dissatisfaction with the Pakeha descriptions of what is and what happened, the covers have only in the last decade or so really begun to be ripped off the struggles of a century before. Some truth is emerging, in the sense of reasonably accurate statements about who did what and why, but so inevitably is a great deal of myth-making, of the casting of villains and the erection of culture-heroes by Maoris to match the villains and culture-heroes which were created earlier by the Pakeha—and which many Pakeha of a post-imperial generation now themselves find very inadequate. In all of this academics are going to become involved, partly because they are going to be dragged into it by the public, by their students and by the media, and partly because it is going to be difficult for some of them to resist the heady attractions of playing to the gallery of one set or another of protagonists or polemicists, frequently eager to have the presumed authority of an academic imprimatur on their particular ver- sion of what is supposed to have happened. -

Te Wairua Kōmingomingo O Te Māori = the Spiritual Whirlwind of the Māori

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WAIRUA KŌMINGOMINGO O TE MĀORI THE SPIRITUAL WHIRLWIND OF THE MĀORI A thesis presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Māori Studies Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Te Waaka Melbourne 2011 Abstract This thesis examines Māori spirituality reflected in the customary words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Maori. Within these words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Māori; the past and present creates the dialogue sources of Māori understandings of its spirituality formed as it were to the intellect of Māori land, language, and the universe. This is especially exemplified within the confinements of the marae, a place to create new ongoing spiritual synergies and evolving dialogues for Māori. The marae is the basis for meaningful cultural epistemological tikanga Māori customs and traditions which is revered. Marae throughout Aotearoa is of course the preservation of the cultural and intellectual rights of what Māori hold as mana (prestige), tapu (sacred), ihi (essence) and wehi (respect) – their tino rangatiratanga (sovereignty). This thesis therefore argues that while Christianity has taken a strong hold on Māori spirituality in the circumstances we find ourselves, never-the-less, the customary, and traditional sources of the marae continue to breath life into Māori. This thesis also points to the arrival of the Church Missionary Society which impacted greatly on Māori society and accelerated the advancement of colonisation. -

Native Decolonization in the Pacific Rim: from the Northwest to New Zealand

NATIVE DECOLONIZATION IN THE PACIFIC RIM: FROM THE NORTHWEST TO NEW ZEALAND KRISTINA ACKLEY AND ZOLTÁN GROSSMAN, FACULTY CLASS TRIP AND STUDENT PROJECTS, THE EVERGREEN STATE COLLEGE, OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON, USA, FEBRUARY-APRIL 2015 KAUPAPA MAORI PRACTICES 1. Aroha ki tangata (a respect for people). 2. Kanohi kitea (the seen face). 3. Titiro, whakarongo…korero (look, listen…speak). 4. Manaaki ki te tangata (share, host people, be generous). 5. Kia tupato (be cautious). 6. Kaua e takahia te mana o te tangata (do not trample over the mana of people). 7. Kaua e mahaki (don’t flaunt your knowledge). Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies (p. 120) Booklet available as a PDF color file: http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/NZ 2015.pdf CONTENTS 3. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION MAPS: 4. New Zealand 5. Maori population and Orakei Maori iwi (tribes) Marae (Maori 2015 STUDY TOUR: 6. Itinerary & Faculty community) 7. Auckland Museums, Feb. 17-18 in Auckland 8. Indigenous Resilience in Auckland, Feb. 16, 19-20 9. Rotorua, Feb. 21-22 10. Whakatane, Feb. 23-24 11. Waipoua Forest, Feb. 25-27 12. Waitangi / Bay of Islands, Feb. 28-Mar. 1 Photos of Study Tour by Zoltán Grossman More photos available at http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/NZ2015.html STUDENT PROJECTS 14. Sarah Bond-Yancey, “The Patterns that Survive: How Indigenous Spatial Resilience Can Inform Inclusive Planning Practices to Guide Our Future” 15. Annie Bouffiou, “Hearing People in a Hard of Hearing Place: If I Did To You What You Do To Me… “ 16. Jessica Cook, “The Indian Child Welfare Act and the Struggles it Faces” 17. -

CHAPTER TWO Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki

Te Kooti’s slow-cooking earth oven prophecy: A Patuheuheu account and a new transformative leadership theory Byron Rangiwai PhD ii Dedication This book is dedicated to my late maternal grandparents Rēpora Marion Brown and Edward Tapuirikawa Brown Arohanui tino nui iii Table of contents DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER TWO: Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki .......................................................... 18 CHAPTER THREE: The Significance of Land and Land Loss ..................................... 53 CHAPTER FOUR: The emergence of Te Umutaoroa and a new transformative leadership theory ................................................................................................. 74 CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion: Reflections on the Book ................................................. 83 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................ 86 Abbreviations AJHR: Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives MS: Manuscript MSS: Manuscripts iv CHAPTER ONE Introduction Ko Hikurangi te maunga Hikurangi is the mountain Ko Rangitaiki te awa Rangitaiki is the river Ko Koura te tangata Koura is the ancestor Ko Te Patuheuheu te hapū Te Patuheuheu is the clan Personal introduction The French philosopher Michel Foucault stated: “I don't -

Treaty Ill History 2020 AI.Indd

BRIDGET WILLIAMS information sheet BOOKS The Treaty of Waitangi | Te Tiriti o Waitangi An Illustrated History (new edition) Claudia Orange Claudia Orange’s writing on the Treaty has contributed to New Zealanders’ understanding of this history for over thirty years. In this new edition of her popular illustrated history, Dr Orange brings the narrative of Te Tiriti/Treaty up to date, covering major developments in iwi claims and Treaty settlements – including the ‘personhood’ established for the Whanganui River and Te Urewera, applications for customary title in the foreshore and seabed, and critical matters of intellectual property, language and political partnership. New Zealand’s commitment to the Treaty claims process has far-reaching implications for this country’s future, and this clear account provides readers with invaluable insights into an all-important history. The Treaty of Waitangi by Claudia Orange was fi rst published in 1987 to national acclaim, receiving the Goodman Fielder Wattie Award. This widely respected history has since advanced through several new editions. The Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi: An Illustrated History is the most comprehensive RRP: $49.99 | paperback | 215 x 265mm account yet, presented in full colour and drawing on 488 pages | over 300 illustrations Dr Orange’s recent research into the nine sheets of the ISBN 9781988587189 Treaty and their signatories. Publication: 8 December 2020 Distributor: David Bateman Ltd PO Box 100 242, North Shore Mail Centre, Auckland 0745 | (09) 415 7664 extn 0 [email protected] Sales Manager: Bryce Gibson (09) 415 7664 extn 811 | [email protected] Sales Representatives: KEY POINTS Murray Brown – Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Coromandel , Auckland, Northland • A comprehensive and beautifully illustrated history 021 278 6396 | [email protected] of the Treaty that is accessible to the general reader. -

Phanzine, December 2018

INSIDE 2 Naenae and me 4 Auckland Heritage Festival 5 Summer holidays and heritage Phanzine 6 Improving protection Newsletter of the 7 Feminist engagements Professional Historians’ Association of New Zealand /Aotearoa 8 Comment Vol. 24, No. 3, December 2018 ► ISSN 1173 4124 ► www.phanza.org.nz 9 Members’ publications Spreading the load: Makatote Viaduct and train, circa 1910. Mount Ruapehu is in the background. William Beattie & Company. Ref: PAColl-7081-09. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. / records/23078548 Editorial The Future of PHANZA Our AGM has come and gone and a new committee, of committee members this year and filling the with some old and new faces, has begun work. This committee and getting all our necessary work done coming year will be a challenging one, with a confer- is becoming increasingly challenging. Seeing first- ence in April 2019 and other initiatives to get across hand just how much work has to be done just to fulfil the line, including our member grants’ fund, which Companies Office requirements does make me won- we have had to defer until the conference is done der whether we need to rethink the burden on our and dusted. committee, particularly office holders. Do we need to Next year PHANZA will turn 25 and this will be consider creating new positions to spread the load, something to celebrate. Such a milestone seemed or even paying someone to manage the organisa- a long way off to those of us who attended the very tion’s affairs? If any member has a view on this, feel first meeting to set up the organisation.