Trends in Contemporary Italian Narrative 1980-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Librib 501200.Pdf

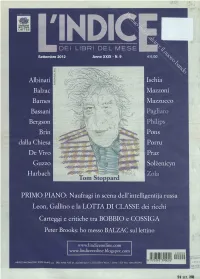

FONDAZIONE BOTTARI LATTES Settembre 2012 Anno XXIX - N. 9 Albinati Ischia Balzac Mazzoni Barnes Mazzucco Bassani Bergson Brin Pons dalla Chiesa Porru De Vivo Praz Guzzo Solzenicyn Harbach PRIMO PIANO: Naufragi in scena del?intelligenti)a russa Leon, Gallino e la LOTTA DI CLASSE dei ricchi Carteggi e critiche tra BOBBIO e COSSIGA Peter Brooks: ho messo BALZAC sul lettino www.lindiceonline.com www.lindiceonline.blogspot.com MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - POSTE ITALIANE s.p.a. - SPED. IN ABB. POST. D.L. 353/2003 (conv.in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. I, comma ], DCB Torino - ISSN 0393-3903 Editoria La verità è destabilizzante Per Achille Erba di Lorenzo Fazio Quando è mancato Achille Erba, uno dei fon- ferimento costante al Vaticano II e all'episcopa- a domanda è: "Ma ci quere- spezzarne il meccanismo di pro- datori de "L'Indice", alcune persone a lui vicine to di Michele Pellegrino) sono ampiamente illu- Lleranno?". Domanda sba- duzione e trovare (provare) al- hanno deciso di chiedere ospitalità a quello che lui strate nel sito www.lindiceonline.com. gliata per un editore che si pre- tre verità. Come editore di libri, ha continuato a considerare Usuo giornale - anche È opportuna una premessa. Riteniamo si sarà figge il solo scopo di raccontare opera su tempi lunghi e incrocia quando ha abbandonato l'insegnamento universi- tutti d'accordo che le analisi e le discussioni vol- la verità. Sembra semplice, ep- passato e presente avendo una tario per i barrios di Santiago del Cile e, successi- te ad illustrare e approfondire nei suoi diversi pure tutta la complessità del la- prospettiva anche storica e più vamente, per una vita concentrata sulla ricerca - aspetti la ricerca storica di Achille e ad indivi- voro di un editore di saggistica libera rispetto a quella dei me- allo scopo di convocare un'incontro che ha lo sco- duare gli orientamenti generali che ad essa si col- di attualità sta dentro questa pa- dia, che sono quotidianamente po di ricordarlo, ma anche di avviare una riflessio- legano e che eventualmente la ispirano non pos- rola. -

Curriculum Vitae E Studiorum

GIULIA TELLINI CURRICULUM VITAE E STUDIORUM FORMAZIONE . Dottorato di ricerca in Storia dello Spettacolo, conseguito in data 16 maggio 2008 presso 1 l’Università degli Studi di Firenze, con tesi dal titolo Una carriera fra cinema e teatro: Gino Cervi nello spettacolo italiano fra primo e secondo dopoguerra, relatore prof. Siro Ferrone. Laurea in Lettere, conseguita in data 17 giugno 2004 presso l'Università degli Studi di Firenze, con tesi in Storia del Teatro e dello Spettacolo dal titolo Attrici per Medea. Interpretazioni del mito tra Otto e Novecento, relatore prof. Siro Ferrone, voto di laurea 110 Lode/110 (centodieci e lode su centodieci). ATTIVITÀ DI RICERCA E INSEGNAMENTI . Dal marzo 2017 è assegnista di ricerca in Letteratura Italiana, Dipartimento di Lettere e Filosofia dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze. Dal 2015 insegna Letteratura teatrale italiana presso l’Università Federico II di Napoli nell’ambito del Master di II livello in Drammaturgia e Cinematografia (12 ore all’anno). Dal 2014 insegna al Florence Program dell’Università di Toronto Mississauga presso l’Accademia Fiorentina di Lingua e Cultura Italiana (72 ore all’anno, fra metà settembre e metà novembre). Dal 2009 tiene il corso di Storia del Teatro italiano presso il Centro di Cultura per Stranieri dell’Università di Firenze (32 ore all’anno). Dall’estate 2008 insegna presso la Scuola Italiana del Middlebury College Language Schools (USA, Vermont e California): 30 ore ogni corso, fra fine giugno e inizio agosto. Nel 2004, 2011, 2012 e 2013, ha tenuto corsi di lingua italiana presso il Centro di Cultura per Stranieri dell’Università di Firenze. -

A Gripping Historical Mystery Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE DAUGHTER OF TIME : A GRIPPING HISTORICAL MYSTERY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Josephine Tey | 224 pages | 14 Sep 2009 | Cornerstone | 9780099536826 | English | London, United Kingdom The Daughter Of Time : A gripping historical mystery PDF Book Compra nuovo EUR 8, Captivating and disturbing, Alias Grace showcases bestselling, Booker Prize-winning author Margaret Atwood at the peak of her powers. The geography of London as it rebuilds is key to the novels, with a wealth of period detail against which the intensely thrilling plots unfold. Riassunto Su questo libro Josephine Tey's classic novel about Richard III, the hunchback king, whose skeleton was discovered in a council carpark, and who was buried in March in state in Leicester Cathedral. True Confessions John Gregory Dunne. Editore: Arrow Yes, there is murder, intrigue and mystery but it is from a much earlier time in history. The Daughter of Time investigates his role in the death of his nephews, the princes in the Tower, and his own death at the Battle of Bosworth. Please follow the detailed Help center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders. Get free personalized book suggestions and recommended new releases. She teams up with Stoker, a taxidermist, and together they seek to uncover the dark secrets that haunt her own past, as well as deaths, disappearances and betrayals. Life is hell for all the slaves, but especially bad for Cora; an outcast even among her fellow Africans, she is coming into womanhood—where even greater pain awaits. The Daughter Of Time : A gripping historical mystery. In the second novel, Hill finds himself enslaved in Barbados and caught up in the brutality of the civil war, even though he is miles from home. -

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © the Poisoned Pen, Ltd

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © The Poisoned Pen, Ltd. 4014 N. Goldwater Blvd. Volume 28, Number 11 Scottsdale, AZ 85251 October Booknews 2016 480-947-2974 [email protected] tel (888)560-9919 http://poisonedpen.com Horrors! It’s already October…. AUTHORS ARE SIGNING… Some Events will be webcast at http://new.livestream.com/poisonedpen. SATURDAY OCTOBER 1 2:00 PM Holmes x 2 WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 19 7:00 PM Laurie R King signs Mary Russell’s War (Poisoned Pen $15.99) Randy Wayne White signs Seduced (Putnam $27) Hannah Stories Smith #4 Laurie R King and Leslie S Klinger sign Echoes of Sherlock THURSDAY OCTOBER 20 7:00 PM Holmes (Pegasus $24.95) More stories, and by various authors David Rosenfelt signs The Twelve Dogs of Christmas (St SUNDAY OCTOBER 3 2:00 PM Martins $24.99) Andy Carpenter #14 Jodie Archer signs The Bestseller Code (St Martins $25.99) FRIDAY OCTOBER 21 7:00 PM MONDAY OCTOBER 3 7:00 PM SciFi-Fantasy Club discusses Django Wexler’s The Thousand Kevin Hearne signs The Purloined Poodle (Subterranean $20) Names ($7.99) TUESDAY OCTOBER 4 Ghosts! SATURDAY OCTOBER 22 10:30 AM Carolyn Hart signs Ghost Times Two (Berkley $26) Croak & Dagger Club discusses John Hart’s Iron House Donis Casey signs All Men Fear Me ($15.95) ($15.99) Hannah Dennison signs Deadly Desires at Honeychurch Hall SUNDAY OCTOBER 23 MiniHistoricon ($15.95) Tasha Alexander signs A Terrible Beauty (St Martins $25.99) SATURDAY OCTOBER 8 10:30 AM Lady Emily #11 Coffee and Club members share favorite Mary Stewart novels Sherry Thomas signs A Study in Scarlet Women (Berkley -

Curriculum Vitae ______

Cristina Della Coletta [email protected] University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive, MC-0406 La Jolla, CA 92093-0406 (858) 534-6270 Curriculum Vitae ____________________________________ Current Positions: Dean of Arts and Humanities, University of California, San Diego. August 2014- Associate Dean of Humanities and the Arts, College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Virginia. July 2011-July 2014. Professor of Italian, Department of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese, University of Virginia. 2006-2014. Education: Ph.D.: 1993, Italian, University of California, Los Angeles. M.A.: 1989, Italian, University of Virginia. LAUREA: 1987, Lingue e Letterature Straniere, Università di Venezia, Italy. Fellowships and Awards: Fellow: Berkeley Institute on Higher Education. UC Berkeley. July 6-11, 2014. Fellow: Institute for Management and Leadership in Education. Harvard Graduate School of Education. June 16-28, 2013. UVA Faculty Mentoring Award: May 2012. University Seminars in International Studies Grant: 2011. UVA nomination for SCHEV Outstanding Faculty Award. Fall 2010. The University of Virginia Alumni Association Distinguished Professor Award. Spring 2010. Fellow: Leadership in Academic Matters Program. Fall 2009. IATH (Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities) Residential Fellowship for Turin 1911: A World’s Fair in Italy Digital Project. 2009-11. IATH Enhanced Associate Fellowship for Turin 1911: A World’s Fair in Italy Digital Project. 2008. Vice President of Research and Graduate Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences Research Grant, 2008. 1 IATH Associate Fellowship for Turin 1911: A World’s Fair in Italy Digital Project. 2007. Vice President of Research and Graduate Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences Research Grant, 2007. -

Letteratura & Fotografia

LETTERATURA & FOTOGRAFIA I a cura di Anna Dolfi BULZONI EDITORE INDICE 9 Premessa di Anna Dolfi 21 Melania Mazzucco, La camera oscura dellafantasia 33 Filippo Secchieri, Due regioni delfigurale 63 Enza Biagini, Francois-Marie Banier: vademecum minimo sulla «Vie de la photo» 77 Michela Landi, La freccia scoccata. Il rituale fotografico di Henri Cartier-Bresson secondo (Valéry, Barthes) Bonnefoy 131 Luigi Tassoni, Biografieper immagini (o immaginiper biografie?) 143 Irene Gambacorti, Ritratti verghiani 205 Michela Toppano, La configurazione dello spazio nella narrativa e nella fotografia di Federico De Roberto 245 Remo Ceserani, // tema della fotografia nell'opera narrativa di Pirandello 265 Giuseppe Girimonti Greco, Note sulla «Recherche» in «camera oscura». Proust, Brassa'iegli «enjeux romanesques» dell'immaginefotografica 319 Pierre Sorlin, Lefotografie interiori di Virginia Woolf 331 Epifanio Ajello, Guido Gozzano. Lafoto che non c'è 345 Eleonora Pinzuti, Scrittura di luce e scrittura di testo nel «Labyrinthe du monde» di Marguerite Yourcenar 367 Indice dei nomi 7 LETTERATURA & FOTOGRAFIA II a cura di Anna Dolfì BULZONI EDITORE INDICE 9 Francesca Serra, Idoli dell'assenza. Tableaux e sparizione nell'opera di Palazzeschi 33 Simone Casini, Moravia dal romanzo al cineromanzo. La deriva in- tersemiotica della «Romana» 61 Paolo Orvieto, Vittorini e l'«accostamento» fotografico 83 Paolo Zublena, Lo sguardo del braccio di tenebra. Landolfi e «la» foto¬ grafia 91 Monica Farnetti, Riscattare fotografie. I romanzi di figure di Lalla Romano 107 Michela Baldini, Luogo e percezione visiva nella scrittura di Giorgio Caproni. Note su «Erba francese» 129 Mireille Calle-Gruber, Un pas de plus. «Photobiographie» de Claude Simon 147 Riccardo Donati, La meccanica del mancato possesso. -

Classics of Detective Fiction: from the 1960S to Today This Series Will

Classics of Detective Fiction II Lecturer: Stefani Nielson Classics of Detective Fiction: From the 1960s to Today This series will consider trends and innovations in detective-suspense fiction since the 1960s. Including works by the esteemed Ross Macdonald, the superstar Ian Rankin and the brash Sara Paretsky among others, the series will focus on the steady growth of "niche" genres within detective-suspense fiction since the close of WWII. A key theme will be how these new forms of detective-suspense fiction speak to the changing times. Storytelling forms we'll examine include post-Chandler American noir, Scandinavian noir, post-Golden Age British historical mystery, the humorous Canadian cozy mystery, and the 21st century female detective story. Questions we'll ask include: has the hard-boiled detective disappeared? can a whodunnit be "serious" literature? what is the gothic detective novel? whatever happened to Sherlock Holmes? does geography matter, eh? what's funny about crime? what's a nice girl like you doing in a crime like this? how does the past affect today? Join us as we discuss the conventions and transformations that keep us reading this intriguing genre. Each week we'll examine one author and a work of fiction, considering how that work expresses its author's unique voice, relates to its own time and yet remains relevant to readers today. Suggested reading schedule: Please note participants are not obligated to do any readings. All readings are available through the public library. Week Author Reading Category 1 -

Claves De Lectura Para La Novela De Melania G. Mazzucco (1996-2016): La Tintoretta O La Recuperación De La Memoria Del Personaje Femenino

UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA Facultad de Filología Departamento de Filología Moderna Claves de lectura para la novela de Melania G. Mazzucco (1996-2016): La Tintoretta o la recuperación de la memoria del personaje femenino TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: José Luis Espinosa Sales Dirigida por: Dr. D. Vicente González Martín Salamanca, 2018 Al profesor D. Joaquín Espinosa Carbonell, mi padre. Le habría gustado esta historia de hijas y padres, de personajes en busca de autor. Índice de contenido INTRODUCCIÓN.........................................................................................................................3 I. LA MUJER DEL MAGMA Y LA PALABRA: .........................................................................9 PERFIL BIOGRÁFICO Y OBRA DE MELANIA G. MAZZUCCO...........................................9 I.1 Magma, épica y realismo: una perspectiva crítica.............................................................13 I.2 La novela en Mazzucco.....................................................................................................19 I.3 Constantes de la narrativa de Mazzucco............................................................................23 I.3.1. El trabajo documental...............................................................................................26 I.3.2 La arquitectura narrativa............................................................................................27 I.3.3 La polifonía................................................................................................................28 -

— a Tavola Con Le Muse Immagini Del Cibo Nella Letteratura Italiana Della

A TAVOLA CON LE MUSE A TAVOLA Italianistica 8 — A tavola con le Muse Immagini del cibo CROTTI, MIRISOLA nella letteratura italiana della modernità a cura di Ilaria Crotti e Beniamino Mirisola Edizioni Ca’Foscari 8 A tavola con le Muse Italianistica Collana diretta da Tiziano Zanato 8 Edizioni Ca’Foscari Italianistica Direttore Tiziano Zanato (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Comitato scientifico Alberto Beniscelli (Università degli Studi di Genova, Italia) Giuseppe Frasso (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Milano, Italia) Pasquale Guaragnella (Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Italia) Niva Lorenzini (Università di Bologna, Italia) Cristina Montagnani (Università degli Studi di Ferrara, Italia) Matteo Palumbo (Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Italia) Carla Riccardi (Università degli Studi di Pavia, Italia) Lorenzo Tomasin (Università di Losanna, Svizzera) Comitato di redazione Saverio Bellomo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Ilaria Crotti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Serena Fornasiero (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Daria Perocco (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Ricciarda Ricorda (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Silvana Tamiozzo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Piermario Vescovo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Direzione e redazione Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici Palazzo Malcanton Marcorà Dorsoduro 3484/D 30123 Venezia URL http://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/it/edizioni/collane/italianistica/ A tavola con le Muse Immagini del cibo nella letteratura -

Facultad De Filosofía Y Letras Colegio De Letras Modernas Departamento De Letras Italianas

Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Colegio de Letras Modernas Departamento de Letras Italianas Seminario de Literatura Femenina Italiana Horario: viernes de 13 a 15 hrs Semestre: 2018-2 Profesora: Eleonora Maria Antonietta Biasin Povoleri Contacto:[email protected] Objetivo(s) del curso: Este seminario se propone rescatar las voces de las escritoras italianas a través de un recorrido por la literatura femenina desde las primeras manifestaciones en la edad media, hasta las obras más recientes. El segundo semestre abarca el periodo histrórico desde la postguerra (1950) hasta la actualidad. Metodología: El acercamiento a los perfiles de las autoras elegidas, así como a algunas de sus páginas más representativas, se realizará con un enfoque crítico, tratando de estimular entre los alumnos la discusión y la capacidad de establecer relaciones entre autoras y obras, así como entre obras y contexto histórico, político, cultural, y otras manifestaciones artísticas como cine, teatro y artes plásticas. De cada autora elegida se presentarán los trazos biográficos esenciales y se leerán y analizarán de manera crítica algunos textos significativos. Se leerán y analizarán críticamente 3 obras completas: La Storia de Elsa Morante Una obra de narrativa o de poesia, elegida libremente por cada estudiante entre las propuestas del primer periodo considerado (de los años 50’s a los 90’s) Una obra de narrativa o de poesia, elegida libremente por cada estudiante entre las propuestas del segundo periodo considerado (del 2000 a la actualidad) Temario Literatura femenina italiana desde la postguerra (1950) hasta la actualidad Análisis y reflexiones acerca de la participación femenina en el mundo de la literatura en el periodo considerado y su importancia desde el punto de vista crítico, histórico, social y psicológico. -

Lone Star Sleuths Bibliography of Texas-Based Mystery/Detective Fiction

Lone Star Sleuths Bibliography of Texas-based Mystery/Detective Fiction A Bibliography of Texas-based Mystery/Detective Fiction Be sure to check out the new anthology, Lone Star Sleuths, available from the University of Texas Press as part of its Southwestern Writers Collection Book Series. Reflecting the remarkable diversity of the state, Texas-based mysteries extend from the Guadalupe Mountains in the west to the Piney Woods of East Texas. This annotated bibliography, arranged according to different regions of the state, helps map out some reading trails for mystery fans. We sought to provide a comprehensive list of mystery authors, although not every title published by each author is included. This list is not intended to provide an exhaustive listing of each book published by each author. Instead, it is intended to simply point the Central Texas way towards further exploration by readers. East Texas This bibliography was originally compiled for an exhibit at the Southwestern Writers Collection, Texas State University, in 2003-2004. It was prepared by Steve Davis, North Texas Assistant Curator of the Southwestern Writers Collection, and by Dr. Rollo K. Newsom, Professor Emeritus at Texas State. Along with Bill Cunningham, Davis and Newsom are South Texas co-editors of Lone Star Sleuths. West Texas This bibliography is not currently being updated, but the compilers do welcome Other Texas Mysteries corrections, additions, elaborations, and other feedback. The bibliography may be updated as time permits. Please send comments to Steve Davis. Further Readings CENTRAL TEXAS MYSTERIES Abbott, Jeff Librarian/sleuth Jordan Poteet solves murders from his home in "Mirabeau," a small town along the Colorado River halfway between Austin and Houston. -

To Be Or Not to Be a Mother: Choice, Refusal, Reluctance and Conflict

intervalla: Special Vol. 1, 2016 ISSN: 2296-3413 To Be or Not to Be a Mother: Choice, Refusal, Reluctance and Conflict. Motherhood and Female Identity in Italian Literature and Culture Essere o non essere madre: Scelta, rifiuto, avversione e conflitto. Maternità e identità femminile nella letteratura e cultura italiane Laura Lazzari AAUW International Postdoctoral Fellow, Georgetown University Affiliated Research Faculty, Franklin University Switzerland Joy Charnley Independent Researcher, Glasgow ABSTRACT This volume of intervalla centres on the themes of choice and conflict, refusal and rejection, and analyses how mothers and non-mothers are perceived in Italian society. The nine essays cover a variety of genres (novel, auto-fiction, theatre) and predominantly address how these perceptions are translated into literary form, ranging from the 1940s to the early twenty-first century. They study topics such as the ambivalent feelings and difficult experiences associated with motherhood (doubt, post-natal depression, infanticide, IVF), the impact of motherhood and non-motherhood on female identity, attitudes towards childless/childfree women, the stereotype of the “good mother,” and the ways in which such stereotypes are rejected, challenged or subverted. Major Italian writers, such as Lalla Romano, Paola Masino, Oriana Fallaci, Laudomia Bonanni and Elena Ferrante, are included in these analyses, alongside contemporary “momoirs” and works by Valeria Parrella, Lisa Corva, Eleonora Mazzoni, Cristina Comencini and Grazia Verasani. KEY WORDS: motherhood, Italian literature, Italian culture, female identity, women’s writing PAROLE CHIAVE: maternità, letteratura italiana, cultura italiana, identità femminile, scrittura delle donne Copyright © 2016 (Lazzari & Charnley). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC by-nc-nd 4.0).