ENUT News 2/2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estonian Art 1/2013 (32)

Estonian 1/2013Art 1 Evident in Advance: the maze of translations Merilin Talumaa, Marie Vellevoog 4 Evident in Advance, or lost (and gained) in translation(s)? Daniele Monticelli 7 Neeme Külm in abstract autarchic ambience Johannes Saar 9 Encyclopaedia of Erki Kasemets Andreas Trossek 12 Portrait of a woman in the post-socialist era (and some thoughts about nationalism) Jaana Kokko 15 An aristocrat’s desires are always pretty Eero Epner 18 Collecting that reassesses value at the 6th Tallinn Applied Art Triennial Ketli Tiitsar 20 Comments on The Art of Collecting Katarina Meister, Lylian Meister, Tiina Sarapu, Marit Ilison, Kaido Ole, Krista Leesi, Jaanus Samma 24 “Anu, you have Estonian eyes”: textile artist Anu Raud and the art of generalisation Elo-Hanna Seljamaa Insert: An Education Veronika Valk 27 Authentic deceleration – smart textiles at an exhibition Thomas Hollstein 29 Fear of architecture Karli Luik 31 When the EU grants are distributed, the muses are silent Piret Lindpere 34 Great expectations Eero Epner’s interview with Mart Laidmets 35 Thoughts on a road about roads Margit Mutso 39 The meaning of crossroads in Estonian folk belief Ülo Valk 42 Between the cult of speed and scenery Katrin Koov 44 The seer meets the maker Giuseppe Provenzano, Arne Maasik 47 The art of living Jan Kaus 49 Endel Kõks against the background of art-historical anti-fantasies Kädi Talvoja 52 Exhibitions Estonian Art is included All issues of Estonian Art are also available on the Internet: http://www.estinst.ee/eng/estonian-art-eng/ in Art and Architecture Complete (EBSCO). Front cover: Dénes Farkas. -

Schools of Estonian Graphic Art in Journalism in the 1930S

SCHOOLS OF ESTONIAN GRAPHIC ART IN JOURNALISM IN THE 1930S Merle Talvik Abstract: The basis for the development and spread of graphic design in the 1920s and 30s in Estonia was the rapid progress of the country’s economy and commerce. The rise in the number of publications led to a greater need for designers. The need for local staff arose in all fields of applied graphics. In the 1930s, graphic artists were trained at two professional art schools – the State Applied Art School (Riigi Kunsttööstuskool) in Tallinn and the Higher Art School (Kõrgem Kunstikool) Pallas in Tartu. The present article focuses on the analyses of the creative work of the graphic artists of both schools, trying to mark the differences and similarities. The State Applied Art School was established in 1914. In 1920, Günther Reindorff started working as a drawing teacher. His teaching methods and the distinguished style of his creative work became an inspiration for an entire generation of Estonian graphic designers. The three well-known students and followers of G. Reindorff were Johann Naha, Paul Luhtein and Hugo Lepik. The teachers and students of the State Applied Art School shaped greatly the appearance of magazines printed in Tallinn. Of modern art movements, art deco found most followers. National ornament became a source for creative work. Distinct composition and beautifully designed legible script are also the features that resulted from the systematic education of the State School of Applied Art. The curriculum of the Higher Art School Pallas, established in 1919, was based on western European art experience. -

Paul Reets Kui Kunstikriitik

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library Tartu Ülikool Filosoofiateaduskond Ajaloo ja arheoloogia instituut Kunstiajaloo õppetool Paul Reets kui kunstikriitik Bakalaureusetöö Koostanud: Gertrud Kikajon Juhendaja: Tiiu Talvistu Tartu 2013 Olen bakalaureusetöö kirjutanud iseseisvalt. Kõigile töös kasutatud teiste autorite töödele, põhimõttelistele seisukohtadele ning muudest allikaist pärinevatele andmetele on viidatud. Autor: Gertrud Kikajon ................................................................... (allkiri) ....................................................................... (kuupäev) 2 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Biograafia ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Tallinn ja noorus ...................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Saksa sõjavägi 1943–1945 ....................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Bonni ülikool ............................................................................................................................ 9 1.4 Ameerika ja Harvardi ülikool ................................................................................................. 10 -

Eesti Kunstimuuseumi Toimetised Proceedings of the Art Museum of Estonia

4 [9] 2014 EESTI KUNSTIMUUSEUMI TOIMETISED PROCEEDINGS OF THE ART MUSEUM OF ESTONIA 4 [9] 2014 Naiskunstnik ja tema aeg A Woman Artist and Her Time 4 [9] 2014 EESTI KUNSTIMUUSEUMI TOIMETISED PROCEEDINGS OF THE ART MUSEUM OF ESTONIA Naiskunstnik ja tema aeg A Woman Artist and Her Time TALLINN 2014 Esikaanel: Lydia Mei (1896−1965). Natalie Mei portree. 1930. Akvarell. Eesti Kunstimuuseum On the cover: Lydia Mei (1896−1965). Portrait of Natalie Mei. 1930. Watercolour. Art Museum of Estonia Ajakirjas avaldatud artiklid on eelretsenseeritud. All articles published in the journal were peer-reviewed. Toimetuskolleegium / Editorial Board: Kristiāna Ābele, PhD (Läti Kunstiakadeemia Kunstiajaloo Instituut, Riia / Institute of Art History of Latvian Academy of Art, Riga) Natalja Bartels, PhD (Venemaa Kunstide Akadeemia Kunstiajaloo ja -teooria Instituut, Moskva / Research Institute of Theory and History of Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow) Dorothee von Hellermann, PhD (Oxford) Irmeli Hautamäki, PhD (Helsingi Ülikool ja Jyväskylä Ülikool / University of Helsinki and University of Jyväskylä) Sirje Helme, PhD (Eesti Kunstimuuseum, Tallinn / Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn) Ljudmila Markina, PhD (Riiklik Tretjakovi Galerii, Moskva / State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) Piotr Piotrovski, PhD (Adam Mickiewiczi Ülikool, Poznan / Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan) Kadi Polli, MA (Tartu Ülikool / University of Tartu) Peatoimetaja / Editor-in-chief: Merike Kurisoo Koostaja / Compiler: Kersti Koll Toimetajad / Editors: Kersti Koll, Merike Kurisoo Keeletoimetaja -

Kadri Asmer LETTERS from the PAST: ARMIN TUULSE's ARCHIVE

219 Kadri Asmer LETTERS FROM THE PAST: ARMIN TUULSE’S ARCHIVE IN TARTU The creative legacy of Armin Tuulse (1907–1977, Neumann until 1936), the first Estonian art history professor and scholar of art and architecture, is meaningful in the context of Estonia, as well as Western and Northern Europe. He gained international recognition for his works on medieval architecture, in which he focused on the fortresses, castles and churches of the Baltic and Nordic countries. As a professor at the University of Tartu, and later at Stockholm University, he built a bridge between pre-war art history and its future researchers, and more broadly between Estonia and Sweden. Tuulse’s work and teachings became an important guide for his successors, who have continued and supplemented his research work on the Middle Ages. At the University of Tartu, this baton was handed off to Kaur Alttoa, who has been carrying it forward for decades. In 2015, the correspondence of Armin Tuulse, and his wife Liidia Tuulse (1912–2012) arrived at the Estonian Cultural History Archives from Sweden1 and currently needs to be put in order and systematised. Based thereon, it is very difficult to determine the exact size of the archive, but we can speak about hundreds of letters that were sent to Tuulse starting in 1944. A significant part of the archive DOI: https://doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2017.13.10 Translated by Juta Ristsoo. 1 Estonian Cultural History Archives of the Estonian Literary Museum, Reg. 2015/53. 220 K ADRI ASMER ARMIN TUULSE’S ARCHIVE IN TARTU 221 NOTES ON ARMIN TUULSE AND THE TEACHING OF ART HISTORY IN TARTU In order to understand the importance of Armin Tuulse’s work, and more broadly, the developmental direction of art history as an independent discipline at the University of Tartu, one must go back to the last century, to the 1920s and 1930s. -

As of January 2012 Estonian Archives in the US--Book Collection3.Xlsx

Indexed by Title Estonian Archives in the US Book Collection Author Title Date Dewey # Collect Saar, J1. detsember 1924 Tallinnas 1925 901 Saa Eesti Vangistatud Vaba‐ dusvõitlejate 1. Kogud VII, 2. Kogud VIII‐XIII, 3. Kogud XIV‐XIX, 4. nd 323 Ees Abistamis‐ keskus Kogud XX‐XXV 1985‐1987 Simre, M1. praktiline inglise keele grammatika >1945 422 Sim DP Sepp, Hans 1. ülemaailmne eesti arstide päev 1972 610 Sep EKNÜRO Aktsioonikomitee 1.Tõsiolud jutustavad, nr. 1, 2. nr.2, 3. nr.3 1993 323 EKN Eesti Inseneride Liit 10 aastat eesti inseneride liitu: 1988‐1999 nd 620 Ees Reed, John 10 päeva mis vaputasid maailma 1958 923.1 Re Baltimore Eesti Selts 10. Kandlepäevad 1991 787.9 Ba Koik, Lembit 100 aastat eesti raskejõustikku (1888‐1988) 1966 791 Koi Eesti Lauljate Liit 100 aastat eesti üldlaulupidusid 1969 782 Ees Wise, W H 100 best true stories of World War II, The 1945 905 Wis Pajo, Maido 100 küsimust ja vastust maaõigusest 1999 305 Paj Pärna, Ants 100 laeva 1975 336.1 Pä Plank, U 100 Vaimulikku laulu 1945 242 Pla DP Sinimets, I 1000 fakti Nõukogude Eestist 1981 911.1 Si Eesti Lauljate Liit Põhja‐ Ameerikas 110.a. juubeli laulupeo laulud 1979 780 Ees 12 märtsi radadel 1935 053 Kak Tihase, K12 motiivi eesti taluehitistest 1974 721.1 Ti Kunst 12 reproduktsiooni eesti graafikast 1972 741.1 K Laarman, Märt 12 reproduktsiooni eesti graafikast 1973 741.1 La 12. märts 1934 1984 053 Kak 12. märts. Aasta riiklikku ülesehitustööd; 12. märts 1934 ‐ 12, 1935 053 Kak märts. 1935 Eesti Lauljate Liit Põhja‐ Ameerikas 120.a. -

Kulturhuset 35 Red.Pdf

0861 JaQWa)das L - gnf t' I a~paAs ! Jf Sf ' - Hfli'IflX H30 ISNOX XSINIS~ Produktion: Stockholms Kulturförvaltning, konstavdelningen Utställningsansvarig: Co Derr Assistent: Kersti Wikström Arbetsgrupp för utställning och katalog: Co Derr, Kersti Wikström, Beate Sydhoff Konsulter: Ilmar Laaban, Otto Paju Översättningar: Ilmar Laaban Affisch: Enno Hallek Foto: Per Bergström Tekniskt ansvariga: Olle Noren, Tage Lundströmer Information: Kersti Wikström, Co Derr Layout: Otto Paju Tryckeri: AB Danagård Grafiska. Printed in Sweden. Copyright 0 Artikelförfattarna. För återgivning av text utöver citaträtten erfordras överenskommelse med varje enskild författare. Beträffande återgivning av bilder hänvisas till respektive innehavare av upphovsrätten. ISBN 91-7260-438-7 Adress: Kulturhuset, Sergels torg 12, Box 7653, 103 94 Stockholm. Tel. 08/14 11 20 Öppettider: Måndagar stängt Tisdag 11-22 Onsdag 11-18 (Fr. 1/9 11-20.30) Torsdag 11-18 (Fr. 1/9 11-20.30) Fredag 11-18 Lördag 11-17 (Fr. 1/9 11-18) Söndag 11-17 (Fr. 1/9 11-18) 2 Innehåll 4 Förord, Beate Sydhoff. 6 Sten Karlin g, Konst och konstnärer i 1930-talets Tartu. 12 Endel Köks, Som konststuderande i Tartu. 18 Hmar Laaban, Från målad utopi till vardag och vision. 26 Hmar Laaban, Andningshålet och äventyret. 34 Hain Rebas, Några aspekter på temat "Esterna i Sverige". 42 Konstnärsbiografier. 3 47 Litteraturförslag. Det är nu trettiofem år sedan den estniska invandringen till Sverige ägde rum. De estniskfödda svenska medborgarna är den första stora invandrargrupp under 1900-talet som tillfört Sverige sin kultur och sina seder. Deras bakgrund visar en samlad kulturbild som i dagens perspektiv framstår som en tidig förelöpare till de andra etniska grupper som i ett senare skede invandrat till vårt land. -

Estonian Art in Australia Mellik and in Perth Under Lvor Hunt, 46 Eesti Kunst Austraalias

Authors Contents Richard Antik, Toronto, Canada Director of the Estonian Centra/ Archi ves in Canada. Graduated from the Uni versity of Tartu. Studied at the Karlovy University in Prague. Subjects: archiva/ and library sciences and history of art. Author of 10 special works, inc/uding "The Estonian Book 1535-1935", Tartu 1936. Arranged Estonian art exhibitions, one in Denmark at the Roya/ Danish Academy of Arts and several others in Canada. Owner of an Art Ga/lery in Cana da. Has worked as an art critic and is known as the author of several articles on Estonian art and cu/ture. Eevi End, Stockholm, Sweden Art history studies at Tartu University, Estonia, 1934-1939. Employed by the 10 Estonian Art in Sweden Estonian National Museum ofArts 1939- 18 Eesti kunstnikest Rootsis 43. Reviewed Estonian Art Exhibitions ja Euroopas. 19 71-1980. Articles on the work of Eevi End Estonian artists. 26 Estonian Art in Canada Paul H. Reets, Boston, USA 28 Eesti kunstnikest ja kunstist Art history studies at Bonn University Kanadas. 1945-1950, F reiburg University 1948, Richard Antik MA-Degree Harvard University 1951-53. Published over 90 articles, reviews and 32 Estonian Art in USA aforisms. 34 Eesti kunst USA-s. Pau/ H. Reets Valdemar Vilder, Sydney, Australia Studied art in Ta/linn under prof. V. 44 Estonian Art in Australia Mellik and in Perth under lvor Hunt, 46 Eesti kunst Austraalias. humanities and librarianship at the uni Valdemar Vilder versities of Western Australia, Sydney, 53 Bibliograafia. and New South Wales. Librarian of the Ende/ mks Museum of App/ied Arts and Sciences in Sydney for thirteen years. -

Download Download

Tiiu Talvistu – Karin Luts Article 2, Inferno Volume VIII, 2003 1 KARIN LUTS – AN ARTIST AND HER TIME Tiiu Talvistu At the art exhibition /K. Luts/ Puddles and blotches make ellipses from curves from runs dropping autumn yellow into lakes of ultramarine. Painters’ fields swell. Scythes rotate rod-arms’ rows. Colour substance builds heavy walls where soldiers and workers triumphantly snore. We hammered the fingertips, nails applauded Nov 19581 he twentieth century is of unparalleled significance to Estonian art. During the first two decades of this tumultuous era, the first Estonian-born artists returned to live and work in their homeland. In T1919, shortly after the declaration of independence, the first national institution of art opened its doors in Tartu and soon attained the status of a higher-education establishment. The art school Pallas remained the only institution teaching depictive arts during the short life of the First Republic of Estonia from 1919 to 1940. The teaching staff mainly consisted of artists who had studied in various academies in St. Petersburg, Munich and Paris. Already among the first graduates of 1924, there was a woman, Natali Mei. However, the most distinguished female artist to graduate from Pallas’ faculty of painting, Karin Luts (1904-1993), did so in 1928. The turbulent history of Estonia in the first half of the twentieth century shaped her life along similar lines to many of the cultural figures who lived there during this period. In 1944, when the Armies of Soviet Russia were marching ever closer, tens of thousands tried to flee Estonia in fear of repression and political terror, whether over the sea to Sweden or via land to Germany. -

Endel Kõksi Abstraktsetest Maalidest

Reet Mark ENDEL KÕKSI ABSTRAKTSETEST MAALIDEST Kogu abstraktne kunst polegi muud kui inimese sisemaailma nähtavaks tege- mine. Ja kuigi üksikud väljendused on kahtlemata subjektiivsed, on kõik kokku objektiivne pilt inimvaimust, nii nagu me seda praegu kujutada oskame.1 Endel Kõks, 1970. aastad Kunstnik Endel Kõks (1912–1983) kuulub ühte põlvkonda eesti kunsti klassikute Elmar Kitse ja Lepo Mikkoga. Pärast Kitse ja Kõksi debüüti 1939. aastal Tallinnas Kujutava Kunsti Sihtkapitali Valitsuse (KKSKV) näitusel hakati neist kolmest rääkima kui lootustandvast Tartu kolmi- kust. Paraku läks elu aga teisiti. 1944. aasta sügisel sattus Endel Kõks haavatud sõdurina Saksamaale, Kits ja Mikko jäid Eestisse. Oma ülejää- nud elu elas Kõks paguluses, rändas läbi terve maailma, kuid ei saanud kordagi tagasi koju. Peamiselt sai pagulasaegset loomingut hinnata mustvalge ajakirjanduse vahendusel. Kunstniku eluajal jõudis Eestisse küll tema töid, enamasti graafikat, kuid see ei andnud tema loomin- gust ja selle tasemest süstemaatilist ülevaadet. Abstraktsetest maalidest sai aimu mõne pildi järgi, mis jõudsid Eesti Kunstimuuseumisse alles pärast kunstniku surma. Nii kujunes temast nõukogudeaegses kunsti- teaduses peaaegu millelegi toetumata mulje kui keskpärasest maalijast ja eriti kui nõrgast abstraktsionistist, kuid mille lükkaksin otsustavalt ümber, toetudes aastatel 2008–2011 pagulaskunstinäitust2 ning 2011–2013 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2016.11.07 1 Endel Kõks kirjas Silvia Hinnomile 1970. aastatel. Koopia autori valduses. 2 Näitus „Eesti kunst paguluses“, Kumu (03.09.2010–02.01.2011), Tartu Kunstimuuseum (23.02.2011– 30.04.2011). Kuraatorid: Kersti Koll, Reet Mark ja Tiiu Talvistu. 126 Reet Mark Endel Kõksi abstraktsetest maalidest 127 Endel Kõksi isikunäitust3 ette valmistades4 tehtud järeldustele, mida analüütilisest kubismist välja kasvanud, otsekui mosaiigitükkidest olen täiendanud väliseesti kunstiajaloolaste ja kunstnike arvamustega. -

As of January 2012 Estonian Archives in the US--Book Collection3.Xlsx

Indexed by Author Estonian Archives in the US Book Collection Author Title Date Dewey # Collect 940.19 20. augusti Klubi ja Riigi‐kogu Kantselei Kaks otsustavat päeva Toompeal 19.‐20. august 1991 1996 Kah 3. Eesti Päevade Peakomitee 3. Eesti Päevad 1964 061 Kol A P Meremehe elu ja olu 1902 915 A A/S Näituse Kirjastus Amgam kodukäsitööde valmistamisele 1928 645 AS Estonian top firms 1992‐1996: economic information business A/S Vastus 1997 330 Vas directory Aadli, Marc Samm‐sammult 1988 491 Aad Aadli, Mare comp Eesti kirjanduse radadel 1987 810 Aad Aaloe, A Eesti pangad ja jõed 1969 911.1 Aa Aaloe, Ago Kaali meteoriidi kraaterid 1968 560.1 Aa Aaloe, Ago Ülevaade eesti aluspõhja ja pinnakatte strtigraafiast 1960 560.1 Aal Aaltio, Maija‐Hellikki Finnish for foreigners 3d ed 1967 471 Aal Aarelaid, Aili Ikka kultuurile mõeldes 1998 923 Aar Aarelaid, Aili Kodanikualgatus ja seltsid eesti muutuval kultuuri‐maastikul 1996 335 Aar Aarma, R ed. Redo Randel: vanad vigurid ja vembud 1969 741.5 Aa Aas, Peeter Mineviku Mälestusi; Põlvamaa kodulookogukik 1998 920 Aas Aasalu, Heino Tantsud nõukogude eesti 1974a. Tantsupeoks 1972 793.3 Aa Aasalu, Heino Tantsud nõukogude eesti 1975a. Tantsupeoks 1974 793.3 Aa Aasmaa, Tina Käitumisest 1976 798.1 Aa Aasmäe, Valter Kinnisvaraomaniku ABC 1999 305 Aas Aassalu, Heino Esitantsija 1995 796 Aas Aav, Yrjo Estonian periodicals and books 1970 011Aav Aava, A Laskmine 1972 791.1 Aa Aaver, Eva Lydia Koidula 1843‐1886 nd 921 Koi Aavik, F Entwicicklungsgang der Estnischen Schriftsprache 1948 493 Aav SP Aavik, J Kooli leelo 1947 378 Aav Aavik, J Lauluoeo album, jaanikuu 1928 1928 784.079 Aavik, Joh Leelelised vastuväited 1920 493 Aav Aavik, Johannes 20 Euroopa keelt 1933 400 Aav Aavik, Johannes Aabits ja lugemik 1944 491 Aav Aavik, Johannes Aabits ja lugemik kodule ja koolile 2d ed. -

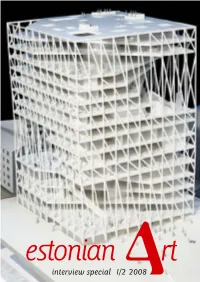

Andreas Trossek and Jaan Toomik

interview special 1/2 2008 1 Prevention magic of monuments Hasso Krull, interviewer Eero Epner 3 A cross for the entire nation Rainer Sternfeld, Andri Laidre, interviewer Liina Siib 5 The public debates Mikko Lagerspetz, interviewer Eero Epner 7 Messages of landscape Merle Karro-Kalberg, interviewer Liina Siib 10 What it meant to be an ‘art historian’ in Soviet Estonia Jaak Kangilaski, interviewer Liina Siib 12 Publicly acknowledged work Marge Monko 14 What can an artist do? What can an artist not do? Laura Kuusk, Margit Säde 17 Why learn more about Jaan Toomik from Wikipedia when you can read a thorough interview instead? Andreas Trossek, Jaan Toomik 21 I constantly feel as if I am some sort of Michael Jackson Viktoria Ladõnskaja, Kristina Norman, Tanja Muravskaja, Liina Siib 27 The idea of location during periods of national self-assurance in Estonian and Finnish art Tiina Abel, Ingrid Sahk, interviewer Liina Siib 31 Eerik Haamer in double exile Reeli Kõiv, interviewer Eero Epner 34 “This is not the Republic of Estonia I have dreamed of” Mart Kalm, interviewer Eero Epner 37 New ‘warm’ brick, ‘worn’ metal, ‘honest’ concrete etc in Rotermann quarter Triin Ojari, interviewer Eero Epner 42 Gas Pipe at the 11th Venice Architecture Biennale Maarja Kask, Neeme Külm, Ralf Lõoke, Ingrid Ruudi interviewers Liina Siib and Eero Epner 45 “The alternativeness is a way of thinking” NG Art Container, interviewer Liina Siib 47 Exhibitions 49 New books interview special 1/2 2008 All issues of Estonian Art are also available on the Internet: www.einst.ee/Ea/ Front cover: SEA+EFFEKT, Denmark.