Musicking-SSCM Conference Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXI, Number 3 Winter 2006 AMERICAN HANDEL SOCIETY- PRELIMINARY SCHEDULE (Paper titles and other details of program to be announced) Thursday, April 19, 2006 Check-in at Nassau Inn, Ten Palmer Square, Princeton, NJ (Check in time 3:00 PM) 6:00 PM Welcome Dinner Reception, Woolworth Center for Musical Studies Covent Garden before 1808, watercolor by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. 8:00 PM Concert: “Rule Britannia”: Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall SOME OVERLOOKED REFERENCES TO HANDEL Friday, April 20, 2006 In his book North Country Life in the Eighteenth Morning: Century: The North-East 1700-1750 (London: Oxford University Press, 1952), the historian Edward Hughes 8:45-9:15 AM: Breakfast, Lobby, Taplin Auditorium, quoted from the correspondence of the Ellison family of Hebburn Hall and the Cotesworth family of Gateshead Fine Hall Park1. These two families were based in Newcastle and related through the marriage of Henry Ellison (1699-1775) 9:15-12:00 AM:Paper Session 1, Taplin Auditorium, to Hannah Cotesworth in 1729. The Ellisons were also Fine Hall related to the Liddell family of Ravenscroft Castle near Durham through the marriage of Henry’s father Robert 12:00-1:30 AM: Lunch Break (restaurant list will be Ellison (1665-1726) to Elizabeth Liddell (d. 1750). Music provided) played an important role in all of these families, and since a number of the sons were trained at the Middle Temple and 12:15-1:15: Board Meeting, American Handel Society, other members of the families – including Elizabeth Liddell Prospect House Ellison in her widowhood – lived in London for various lengths of time, there are occasional references to musical Afternoon and Evening: activities in the capital. -

NEUE DÜSSELDORFER HOFMUSIK Artistic Director and Solo Violin/Directora Artística Y Violín Solista: OUVERTURE NEL PARTENIO (1738) Mary Utiger (Anon

FRANCESCO MARIA VERACINI (1690 - 1768) NEUE DÜSSELDORFER HOFMUSIK Artistic director and solo violin/directora artística y violín solista: OUVERTURE NEL PARTENIO (1738) Mary Utiger (anon. Italian instrument, ca. 1720/anónimo italiano, ca. 1720) [1] (Without indication/sin indicación) 1:15 First violins/violines primeros: [2] Allegro assai 2:23 Veronika Schepping (David Rubio, 1988 after/según Stradivarius) [3] Contadina 2:09 Annette Wehnert (anon. German instrument, end. 18th c./anónimo alemán, finales del s. XVIII) Erik Dorset (Enrico Marchetti, Torino, 19th c./Turín, siglo XIX) CONCERTO A CINQUE [STROMENTI] A MAJOR/LA MAYOR (ca. 1730) Amelia Roosevelt (Richard Duke, London/Londres, 1733) [4] Allegro 3:15 Second violins/violines segundos: [5] Adagio 3:30 Anke Vogelsänger (Landolfi, 1708) / Julia Huber (anon./anónimo, Mantua, ca 1730) [6] Allegro 3:42 llsebil Hünteler (anon. Italian instrument, ca. 1740/anónimo italiano, ca. 1740) Helmut Hausberg (Januarius Gagliano, Naples/Nápoles, 1737) Violas: Bettina lhrig (Ute Wegerhoff, 1990 after/según Stradivarius) CONCERTO A OTTO STROMENTI (1712) Hajo Bäß (anon. German instrument, end. 18th c./anónimo alemán, finales del s. XVIII) [7] (Without indication/sin indicación) 8:35 Christine Moran (Georgius Klotz, Mittenwald, 1725) [8] Largo 4:05 Helmut Hausberg [13-18] (Jo. Battista Cerutti, Cremona, 1789) [9] (Without indication/sin indicación) 7:22 Cellos: Juris Teichmanis (Andreas Ferdinand Mayr, Salzburg/Salzburgo, ca. 1740) Nicholas Selo (English instrument, end. 18th c./instrumento inglés, finales del s. XVIII) CONCERTO A CINQUE [STROMENTI] B FLAT MAJOR/SI B MAYOR (ca. 1736) Bass/contrabajo: Michael Neuhaus (anon. Vienna, mid-18th c./anónimo, Viena, mediados del siglo XVIII) [10] Allegro 3:59 Theorbo/tiorba: Stephan Rath (Joseph Rath, 1985, after/según Martin Hofmann) [11] Largo 3:28 Harpsichord/clave: Christoph Lehmann (Dietrich Hein, 1999, after/según Carl Conrad Fleischer) [12] Allegro 4:00 Oboes: Hans-Peter Westermann (H. -

Mar 1 to 7.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST March 1 - 7, 2021 PLAY DATE: Mon, 3/1/2021 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto No. 7 for violin and cello 6:11 AM Padre Antonio Soler Concierto No. 6 for two obbligato organs 6:25 AM Thomas Simpson Pasameza 6:29 AM Giuseppe Tartini Violin Sonata 6:42 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 10 7:02 AM Johann Georg Pisendel Sonata 7:13 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Andante with Variations HOB XVII:6 7:31 AM Christoph Graupner Concerto for Bassoon,2 violins,viola and 7:43 AM Johann Christian Bach Viola Concerto 8:02 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Partita No. 3 8:15 AM Léo Delibes Coppelia: Excerpts 8:34 AM Gaspar Cassado Sonatine pour Piano et Violoncelle, 1924 9:05 AM Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 9:38 AM Jean Françaix Quartet for English Horn and Strings 9:55 AM Frédéric Chopin Waltz No. 6 10:00 AM Mid-day Classic Choices - TBA 2:00 PM Clara Schumann Notturno (1838) 2:07 PM Benjamin Britten Simple Symphony 2:26 PM Francois Devienne Bassoon Quartet 2:48 PM Antonio Vivaldi Flute Concerto Op 10/3 "The Goldfinch" 3:03 PM Emelie Mayer Piano Trio 3:35 PM Friedrich Kuhlau Concertino for Two Horns and Orchestra 4:01 PM Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Guitar Concerto No. 1 4:23 PM Ferenc Erkel Fantasy duo on Hungarian Airs for violin 4:41 PM Thomas Augustine Arne Organ Concerto No. 2 4:54 PM Robert Lowry How Can I Keep from Singing? 5:01 PM Gustav Holst First Suite for Wind Ensemble 5:13 PM Paul Ben-Haim Sonatina 5:26 PM José Nono Symphony 5:40 PM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Trumpet and Violin 5:54 PM Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber Evita: Don't Cry for Me, Argentina 6:00 PM All Request Hour with Adam Fine 7:00 PM Exploring Music with Bill McGlaughlin 8:00 PM Weeknight Concerts 10:00 PM Performance Today PLAY DATE: Tue, 03/02/2021 6:02 AM Chevalier de Saint-Georges Symphony 6:17 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Sonata No. -

Strauss | Staatskapelle Weimar & Kirill Karabits

Johann Sebastian BACH Sei Solo á Violino senza Basso accompagnato Christoph Schickedanz Sonata No. 1 in G minor, BWV 1001 Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004 I. Adagio 3:43 I. Allemanda 4:59 II. Fuga. Allegro 4:35 II. Corrente 2:33 III. Siciliana 2:41 III. Sarabanda 3:46 IV. Presto 3:14 IV. Giga 3:42 V. Ciaccona 12:55 Partita No. 1 in B minor, BWV 1002 I. Allemanda 5:09 – Sonata No. 3 in C major, BWV 1005 Double 2:39 I. Adagio 3:43 II. Corrente 3:09 – II. Fuga 9:40 Double. Presto 2:59 III. Largo 2:46 III. Sarabande 3:30 – IV. Allegro assai 5:09 Double 2:34 IV. Tempo di Borea 2:55 – Partita No. 3 in E major, BWV 1006 Double 2:59 I. Preludio 3:26 II. Loure 3:39 Sonata No. 2 in A minor, BWV 1003 III. Gavotte en Rondeau 2:39 I. Grave 4:25 IV. Menuet I 1:50 II. Fuga 7:22 V. Menuet II 1:42 III. Andante 4:23 VI. Bourée 1:28 IV. Allegro 5:56 VII. Gigue 1:53 A new horizon, beyond time Yehudi Menuhin referred to the six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin by Johann Sebastian Bach as the “Old Testament for violinists”. Indeed this comparison describes very accurately the high rank that this extraordinary work has assumed in the history of the violin. Transcending genre, it is regarded as a shrine of Western music history, as a miracle of musical timelessness and expressive depth. -

Programmheft Zum Download

PROGRAMM JOHANN DAVID HEINICHEN S i n f o n i a F - D u r „ d i M o r i t z b u r g “ f ü r B l ä s e r, S t r e i c h e r u n d B a s s o c o n t i n u o Allegro – Adagio – Allegro Sarabande Réjouissance La chasse Aimable Allegro Tempo di Minuet La caccia Britta Jacobs und Susanne Winkler, Flöte Veit Stolzenberger, Jürgen Schmitt und Ulrike Broszinski, Oboe Martina Reitmann und Margreth Luise Nußdorfer, Horn JOHANN FRIEDRICH FASCH Lamento für zwei Oboen, zwei Flöten, Klarinette (Chalumeau), Streicher und Basso continuo Andante – Andante – Largo / Un poco allegro Britta Jacobs und Susanne Winkler, Flöte Veit Stolzenberger und Jürgen Schmitt, Oboe Rainer Müller-van Recum, Klarinette to FRANCESCO MARIA VERACINI Concerto Grande da Chiesa für Violine, 2 Trompeten, Pauken, 2 Oboen, Streicher und Basso continuo Allegro Adagio Allegro Mirijam Contzen, Violine Veit Stolzenberger und Jürgen Schmitt, Oboe Uwe Zaiser und Peter Leiner, Trompete Stephan-Valentin Böhnlein, Pauke 1 PAUSE JAN DISMAS ZELENKA Sinfonia a-Moll für 2 Oboen, Fagott, 2 Violinen, Viola, Violoncello und Basso continuo ZWV 189 Allegro Andante Capriccio, Tempo di Gavotta Aria di Capriccio, Andante – Adagio – Allegro – Andante Menuet 1, Menuet 2 Magarete Adorf, Violine Mario Blaumer, Violoncello Veit Stolzenberger und Jürgen Schmitt, Oboe Theo Plath, Fagott GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN Concerto für Violine, 2 Traversflöten, 2 Oboen, 2 Hörner, Pauken, Streicher und Basso continuo F-Dur, T W V 51:F4 Presto Corsiciana – Un poco grave Allegrezza Scherzo Gigue Polacca Minuetto Mirijam Contzen, -

Juilliard415 Program Notes

PROGRAM NOTES On March 4, 1678, an earthquake struck Venice. That same day saw the birth of Antonio Lucio Vivaldi, who, it seems, began as he was meant to continue. Vivaldi sent shockwaves through musical life across Europe over the course of his life; his formal innovations exerted a profound influence on his fellow composers, and his technical virtuosity on the violin set new standards for subsequent generations to live up to. His compositional novelties and charismatic performances did not, however, always endear him to his fellow composers. His most authoritative biographer, Michael Talbot, pithily summarized his social standing with the observations that he “tended to stay aloof from his fellow musicians (especially the most talented of them),” and that of all his noble patrons, none was a fellow Venetian. This afternoon’s program includes the music of several of Vivaldi’s most prominent Venetian contemporaries. Some of them eagerly embraced Vivaldi as a model, and others rejected him, but none was free from his influence. Antonio Lotti, a bit more than ten years older than Vivaldi, was the best-regarded Venetian composer of the generation until Vivaldi’s star rose in the 1710s, and even thereafter was perhaps more universally respected, if less widely known. He spent the majority of his career at San Marco in Venice, rising at the end of his life to the position of maestro di capella. Distinguished as a superb contrapuntal craftsman and accomplished teacher, his secular works did not always rise to the level of his liturgical music; several writers have noted the underdeveloped orchestral writing in his operas. -

Cal Perf February Insert 3.Indd

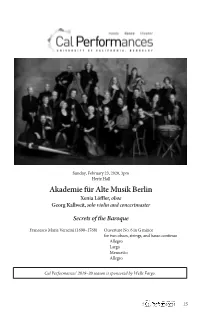

Sunday, February 23, 2020, 3pm Hertz Hall Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin Xenia Löffler, oboe Georg Kallweit, solo violin and concertmaster Secrets of the Baroque Francesco Maria Veracini (1690–1768) Ouverture No. 6 in G minor for two oboes, strings, and basso continuo Allegro Largo Menuetto Allegro Cal Performances’ 2019–20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 25 Unico Wilhelm van Wassenaer (1692–1766) Concerto Armonico No. 5 in F minor for strings and basso continuo Adagio – Largo Da cappella A tempo comodo (con sordini) A tempo giusto Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788) Oboe Concerto in B-flat major, Wq. 164 Allegretto Largo e mesto (con sordini) Allegro moderato Xenia Löffler, oboe INTERMISSION Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767) Sinfonia Melodica, TWV 50:2 for two oboes, strings, and basso continuo Vivace assai Sarabande Bourrée Menuet en Rondeau Loure a l’unison Chaconnette Gigue en Canarie Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725) Concerto Grosso No. 5 in D minor Allegro Grave Gigue: Allegro Minuet Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 4, No. 8 (from La Stravaganza), RV 249 Allegro – Adagio – Presto – Adagio Allegro Georg Kallweit, violin George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) Concerto Grosso in D minor, Op. 3, No. 5, HWV 316 for two oboes, strings, and basso continuo [without indication] Allegro Adagio Allegro ma non troppo Allegro 26 PLAYBILL PROGRAM NOTES Francesco Maria Veracini works. Veracini passed his last years in his na- Ouverture No. 6 in G minor tive Florence, directing the musical activities of for two oboes, strings, and basso continuo the churches of San Pancrazio and San Michele “Veracini was regarded as one of greatest mas- agl’Antinori and occasionally concertizing. -

A Performer's View of Three Recitals

A Performer’s View of Three Recitals Jae-In Shin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ronald G. Patterson, Chair Craig Sheppard Philip D. Schuyler Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2013 Jae-In Shin University of Washington Abstract Performer’s View of Three Recitals Jae-In Shin Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor of Strings, Ronald G. Patterson School of Music The dissertation was presented through the series of three concerts and lectures in both English and Korean based on specific themes for each violin recital and lecture; Baroque Italian music, Brahms’s works, and Romantic French pieces. The first recital included works by Corelli, Tartini, Veracini, and Vitali and took place on October 21st in 2012. The Second, held on February 2nd in 2013, was about Brahms by presenting his first and second violin sonata as well as his piano trio in C minor. In the third recital on March 24th in 2013, the program is ranged from Saint-Saëns and Franck to Ravel and Debussy within the title of French Collection. The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate the diverse characters of music written in different periods and places by providing listeners with music that is also available online with an open access. Included are the program notes and video files from the concerts and lectures. Table of Contents Abstract Recital posters and programs Program notes F. M. Veracini / Violin Sonata in E Minor, Op. 2, No. -

Australian Brandenburg Orchestra VIVALDI OLYMPIA

Australian Brandenburg Orchestra VIVALDI OLYMPIA Paul Dyer Artistic Director Philippe Jaroussky (France) guest soloist, countertenor Program Torelli First movement Allegro from Sinfonia à quattro in C major for four trumpets, G33 Vivaldi Aria “Mentre dormi amor fomenti” from L’Olimpiade, RV 725 Vivaldi Aria “Gemo in un punto e fremo” from L’Olimpiade, RV 725 Handel Concerto grosso in B flat major, Op 6 No 7, HWV 325 Handel Recitative and aria “Pompe vane di morte ... Dove sei?” from Rodelinda, regina de’ Longobardi, HWV 19 Handel Aria “Vivi tiranno!” from Rodelinda, regina de’ Longobardi, HWV 19 INTERvaL Veracini First movement Allegro moderato from Concerto à otto strumenti in D major (1712) Handel Recitative and aria “E vivo ancora? ... Scherza, infida” from the opera Ariodante, HWV 33 Vivaldi Concerto “ripieno” in A major, RV 158 Vivaldi Aria “Vedro con mio diletto” from Il Giustino, RV 717 Handel Battaglia from Rinaldo, HWV 7 Handel Aria “Or la tromba” from Rinaldo, HWV 7 SYDNEY City Recital Hall Angel Place Friday 19, Saturday 20, Wednesday 24, Friday 26, Saturday 27 February 2010 at 7 pm MELBOURNE Melbourne Recital Centre Monday 1, Tuesday 2 March 2010 at 7.30 pm The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra is assisted The Australian Brandenburg by the Australian Government through the Australia Orchestra is assisted by the NSW Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Government through Arts NSW. PRINCIPAL PARTNER Vivaldi Olympia Vivaldi Olympia Paul Dyer artistic director Opera in the time of Handel and Vivaldi Philippe Jaroussky (France) guest soloist, countertenor The first half of the eighteenth century was a boom time for opera, creating new job opportunities for orchestral musicians, stage workers, costume and set designers, and the first “stars” of the entertainment The musicians on world – famous and fabulously wealthy opera singers. -

Unknown Senesino: Francesco Bernardi's Vocal Profile and Dramatic Portrayal, 1700-1740 Randall Scotting Submitted in Fulfilmen

Unknown Senesino: Francesco Bernardi’s Vocal Profile and Dramatic Portrayal, 1700-1740 Randall Scotting Submitted in fulfilment of degree requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Music, London March 2018 Abstract Francesco Bernardi (known as Senesino: 1686-1759) is recognised as one of the most prominent singers of the eighteenth century. With performing credits throughout Europe, he was viewed as a contralto castrato of incredible technical accomplishment in voice and dramatic portrayal. Yet, even considering his fame, success, and frequent and prominent scandals, Senesino has remained little-researched today. The eighteen operas newly composed by George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) for him have been the primary reference sources which define current views of Senesino’s voice.1 For example, regarding the singer’s vocal range, Winton Dean states the following based on Charles Burney’s account of Senesino: ‘His compass in Handel was narrow (g to e″ at its widest, but the g appears very rarely, and many of his parts, especially in later years, do not go above d″) [… ] Quantz’s statement that he had ‘a low mezzo-soprano voice, which seldom went higher than f ″’ probably refers to his earliest years.’2 Dean’s assessment is incomplete and provides an inaccurate sense of Senesino’s actual vocal range, which, in fact, extended beyond his cited range to g''. The upper reaches of Senesino’s voice were not only utilised in his ‘earliest years’ but throughout the entirety of his career. Operas such as Giulio Cesare, Rodelinda, and Orlando account for only a small portion of the 112 operatic works in which the singer is known to have performed during his forty years on stage.3 This thesis expands perceptions of Senesino’s vocal range and aspects of technical skill in vocal and dramatic portrayal to provide an informed sense of the singer from the time of his operatic début to his final years performing. -

Album Booklet

Tartini &Veracini Violin Sonatas Rie Kimura baroque violin Fantasticus RES10148 Tartini & Veracini Francesco Maria Veracini (1690-1768) Italian Violin Sonatas Sonata, Op. 2 No. 12 1. Passagallo [3:50] 2. Capriccio cromatico [3:03] 3. Adagio – Ciaccona [7:29] Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) baroque violin Sonata ‘Il trillo del Diavolo’ Rie Kimura 4. Larghetto affectuoso [5:57] 5. Tempo giusto della Scuola Tartinista [6:01] 6. Andante – Allegro assai [5:33] Fantasticus Francesco Maria Veracini Robert Smith baroque cello Sonata, Op. 2 No. 5 Guillermo Brachetta harpsichord 7. Adagio assai [3:59] 8. Capriccio [4:38] 9. Allegro assai [2:30] 10. Giga [3:53] Giuseppe Tartini Pastorale, Op. 1 No. 13 11. Grave [4:00] 12. Allegro [3:05] 13. Largo – Presto – Largo – Presto – Andante [3:52] About Rie Kimura: ‘Baroque violinist Rie Kimura performs with striking flair and musicianship’ Total playing time [57:58] The Strad ‘Rie Kimura commands a warm and husky gut-string sound, animating the tone so effectively’ International Record Review Tartini & Veracini: Italian Violin Sonatas (and his wife) and devote himself entirely to perfecting his own technique. Veracini, on the One of the most observant musicians in other hand, fed off the excitement of high eighteenth-century England was the society and unqualified adulation, and historian Charles Burney who published nowhere were the pickings richer than in his General History of Music in 1789. No early Georgian London. But not everybody recent composer or performer worth his was impressed. The music-writer and theorist salt escaped Burney’s notice, nor often Roger North heard one of Veracini’s first his censure. -

Summer 2020 Classics & Jazz

Recommended Jazz v All Recommended! see pages 54 - 55 Naxos Audiobooks Special Low Prices! see pages 46 - 47 50% - 75% Off 100 Titles see pages 18 - 21 v All Recommended! Editor’s Choice see pages 10 - 11 v Recommended New Releases Bundle Deal 3 for $30 see pages 48 - 49 Late Summer 2020 Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz We are pleased to present the HBDirect Classics & Summer 2020 Jazz Catalog for Summer 2020, with a broad range of of- fers we’re sure will be of great interest to our customers. Catalog Index Monteverdi: Complete Madrigals / Delitiæ Musicæ [15 CDs] In jazz, we are excited to return Concord to these pages The madrigal, written for courts and patrons, was the ultimate secular 4 Classical - Label Features as a sale label, with the opportunity for you to save even song. The genre reached its zenith with the works of Claudio Monteverdi more by taking advantage of a bundle deal. Other offers 8 Classical - Recommendations in successive books that trace his technical and expressive innovations. in jazz include the Acrobat label, new releases, and jazz 10 Classical - Editor’s Choice In them, Monteverdi explored themes such as the vicissitudes and recommendations. In classical music, another label long pleasures of love, as well as the art of war, and the pain of loss. The 18 Classical - Deep Discounts absent from our promotions is Musical Concepts – on sale editions used in these recordings are the most authentic and uncut, and, here and as a bundle deal, too. You can also save up to 12 Classical - New Releases in keeping with 17th-century practice, employ male voices only.