Cal Perf February Insert 3.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Breath of New Life GLO 5264

A BREATH OF NEW LIFE Dutch Baroque music on original recorders from private collections Saskia Coolen - Patrick Ayrton - Rainer Zipperling GLO 5264 GLOBE RECORDS 1. Prelude in G minor (improvisation) [a] 1.37 WILLEM DE FESCH (1687-1760) Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 8 [e] UNICO WILHELM 12. Ceciliana 2:00 VAN WASSENAER (1692-1766) 13. Allemanda 3:47 Sonata seconda in G minor [b] 14. Arietta. Larghetto e piano 2:16 2. Grave 2:36 15. Menuetto primo e secondo 3:08 3. Allegro 2:54 4. Adagio 1:34 PIETER BUSTIJN (1649-1729) 5. Giga presto 2:26 Suite No. 8 in A major 16. Preludio 1.43 CAROLUS HACQUART (1640-1701?) 17. Allemanda 3.33 Suite No. 10 in A minor from Chelys 18. Corrente 1.52 6. Preludium. 19. Sarabanda 2.20 Lento - Vivace - Grave 2:46 20. Giga 2.02 7. Allemande 2:26 8. Courante 1:29 From: Receuil de plusieurs pièces 9. Sarabande 2:48 de musique […] choisies par Michel 10. Gigue 1:48 de Bolhuis (1739) [f] 21. Marleburgse Marche 1.16 11. Prelude in C minor (improvisation) [d] 1.27 22. Tut, tut, tut 1.04 23. O jammer en elende 1.09 24. Savoijse kool met Ossevleis 1.28 25. Bouphon 1.18 2 JOHAN SCHENCK (1660-1712) Suite in D minor from Scherzi musicali 26. Preludium 1:36 27. Allemande 2:34 28. Courant 1:29 29. Sarabande 1:59 30. Gigue 1:45 Saskia Coolen 31. Tempo di Gavotta 1:25 recorder, viola da gamba Patrick Ayrton PHILIPPUS HACQUART (1645-1692) 1.40 harpsichord 32. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXI, Number 3 Winter 2006 AMERICAN HANDEL SOCIETY- PRELIMINARY SCHEDULE (Paper titles and other details of program to be announced) Thursday, April 19, 2006 Check-in at Nassau Inn, Ten Palmer Square, Princeton, NJ (Check in time 3:00 PM) 6:00 PM Welcome Dinner Reception, Woolworth Center for Musical Studies Covent Garden before 1808, watercolor by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. 8:00 PM Concert: “Rule Britannia”: Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall SOME OVERLOOKED REFERENCES TO HANDEL Friday, April 20, 2006 In his book North Country Life in the Eighteenth Morning: Century: The North-East 1700-1750 (London: Oxford University Press, 1952), the historian Edward Hughes 8:45-9:15 AM: Breakfast, Lobby, Taplin Auditorium, quoted from the correspondence of the Ellison family of Hebburn Hall and the Cotesworth family of Gateshead Fine Hall Park1. These two families were based in Newcastle and related through the marriage of Henry Ellison (1699-1775) 9:15-12:00 AM:Paper Session 1, Taplin Auditorium, to Hannah Cotesworth in 1729. The Ellisons were also Fine Hall related to the Liddell family of Ravenscroft Castle near Durham through the marriage of Henry’s father Robert 12:00-1:30 AM: Lunch Break (restaurant list will be Ellison (1665-1726) to Elizabeth Liddell (d. 1750). Music provided) played an important role in all of these families, and since a number of the sons were trained at the Middle Temple and 12:15-1:15: Board Meeting, American Handel Society, other members of the families – including Elizabeth Liddell Prospect House Ellison in her widowhood – lived in London for various lengths of time, there are occasional references to musical Afternoon and Evening: activities in the capital. -

NEUE DÜSSELDORFER HOFMUSIK Artistic Director and Solo Violin/Directora Artística Y Violín Solista: OUVERTURE NEL PARTENIO (1738) Mary Utiger (Anon

FRANCESCO MARIA VERACINI (1690 - 1768) NEUE DÜSSELDORFER HOFMUSIK Artistic director and solo violin/directora artística y violín solista: OUVERTURE NEL PARTENIO (1738) Mary Utiger (anon. Italian instrument, ca. 1720/anónimo italiano, ca. 1720) [1] (Without indication/sin indicación) 1:15 First violins/violines primeros: [2] Allegro assai 2:23 Veronika Schepping (David Rubio, 1988 after/según Stradivarius) [3] Contadina 2:09 Annette Wehnert (anon. German instrument, end. 18th c./anónimo alemán, finales del s. XVIII) Erik Dorset (Enrico Marchetti, Torino, 19th c./Turín, siglo XIX) CONCERTO A CINQUE [STROMENTI] A MAJOR/LA MAYOR (ca. 1730) Amelia Roosevelt (Richard Duke, London/Londres, 1733) [4] Allegro 3:15 Second violins/violines segundos: [5] Adagio 3:30 Anke Vogelsänger (Landolfi, 1708) / Julia Huber (anon./anónimo, Mantua, ca 1730) [6] Allegro 3:42 llsebil Hünteler (anon. Italian instrument, ca. 1740/anónimo italiano, ca. 1740) Helmut Hausberg (Januarius Gagliano, Naples/Nápoles, 1737) Violas: Bettina lhrig (Ute Wegerhoff, 1990 after/según Stradivarius) CONCERTO A OTTO STROMENTI (1712) Hajo Bäß (anon. German instrument, end. 18th c./anónimo alemán, finales del s. XVIII) [7] (Without indication/sin indicación) 8:35 Christine Moran (Georgius Klotz, Mittenwald, 1725) [8] Largo 4:05 Helmut Hausberg [13-18] (Jo. Battista Cerutti, Cremona, 1789) [9] (Without indication/sin indicación) 7:22 Cellos: Juris Teichmanis (Andreas Ferdinand Mayr, Salzburg/Salzburgo, ca. 1740) Nicholas Selo (English instrument, end. 18th c./instrumento inglés, finales del s. XVIII) CONCERTO A CINQUE [STROMENTI] B FLAT MAJOR/SI B MAYOR (ca. 1736) Bass/contrabajo: Michael Neuhaus (anon. Vienna, mid-18th c./anónimo, Viena, mediados del siglo XVIII) [10] Allegro 3:59 Theorbo/tiorba: Stephan Rath (Joseph Rath, 1985, after/según Martin Hofmann) [11] Largo 3:28 Harpsichord/clave: Christoph Lehmann (Dietrich Hein, 1999, after/según Carl Conrad Fleischer) [12] Allegro 4:00 Oboes: Hans-Peter Westermann (H. -

Mar 1 to 7.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST March 1 - 7, 2021 PLAY DATE: Mon, 3/1/2021 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto No. 7 for violin and cello 6:11 AM Padre Antonio Soler Concierto No. 6 for two obbligato organs 6:25 AM Thomas Simpson Pasameza 6:29 AM Giuseppe Tartini Violin Sonata 6:42 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 10 7:02 AM Johann Georg Pisendel Sonata 7:13 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Andante with Variations HOB XVII:6 7:31 AM Christoph Graupner Concerto for Bassoon,2 violins,viola and 7:43 AM Johann Christian Bach Viola Concerto 8:02 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Partita No. 3 8:15 AM Léo Delibes Coppelia: Excerpts 8:34 AM Gaspar Cassado Sonatine pour Piano et Violoncelle, 1924 9:05 AM Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 9:38 AM Jean Françaix Quartet for English Horn and Strings 9:55 AM Frédéric Chopin Waltz No. 6 10:00 AM Mid-day Classic Choices - TBA 2:00 PM Clara Schumann Notturno (1838) 2:07 PM Benjamin Britten Simple Symphony 2:26 PM Francois Devienne Bassoon Quartet 2:48 PM Antonio Vivaldi Flute Concerto Op 10/3 "The Goldfinch" 3:03 PM Emelie Mayer Piano Trio 3:35 PM Friedrich Kuhlau Concertino for Two Horns and Orchestra 4:01 PM Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Guitar Concerto No. 1 4:23 PM Ferenc Erkel Fantasy duo on Hungarian Airs for violin 4:41 PM Thomas Augustine Arne Organ Concerto No. 2 4:54 PM Robert Lowry How Can I Keep from Singing? 5:01 PM Gustav Holst First Suite for Wind Ensemble 5:13 PM Paul Ben-Haim Sonatina 5:26 PM José Nono Symphony 5:40 PM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Trumpet and Violin 5:54 PM Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber Evita: Don't Cry for Me, Argentina 6:00 PM All Request Hour with Adam Fine 7:00 PM Exploring Music with Bill McGlaughlin 8:00 PM Weeknight Concerts 10:00 PM Performance Today PLAY DATE: Tue, 03/02/2021 6:02 AM Chevalier de Saint-Georges Symphony 6:17 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Sonata No. -

The Musicians of Ma'alwyck

Musicians of Ma’alwyck Presents Beethoven 250th Anniversary Celebration Concert Sunday, November 1, 2020 @ 3pm Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site Dear Friend, Thank you for joining us virtually today. We are sorry we cannot be enjoying this program together here in the music salon of the Schuyler Mansion, but we are pleased that we can still celebrate Beethoven’s landmark year together even if it is just on line. The program we have prepared for you features both the well-known and charming Serenade op 25, which we have transcribed to include guitar instead of viola, the early duo Woo 26 and then a wonderful Potpourri of Beethoven’s Favorite Melodies by Anton Diabelli. Each work displays a different side of Beethoven, whether a young still forming genius or the lighter occasional music side. The acoustic in the Schuyler Mansion allows for nuanced playing and recreates a setting for Beethoven’s that is historically quite accurate. We will continue throughout the duration of COVID restrictions to offer creative programming. Much of the virtual work we are doing is available on the Musicians of Ma’alwyck Youtube channel. I also write a weekly Musical Treasure Chest about pieces important to me that is available on our website, and the ensemble in various configurations performs every Sunday at 3pm on the First Reformed Church of Schenectady’s Youtube channel. Each month we are releasing a “short” video collaborating with historic sites and other artistic media. Our first “short” was filmed in October in the Crypt at Hyde Hall near Cooperstown, New York. -

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Advisory Board Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska, Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Published within the Project HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area) – JRP (Joint Research Programme) Music Migrations in the Early Modern Age: The Meeting of the European East, West, and South (MusMig) Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska, Eds. Warsaw 2016 Liber Pro Arte English Language Editor Shane McMahon Cover and Layout Design Wojciech Markiewicz Typesetting Katarzyna Płońska Studio Perfectsoft ISBN 978-83-65631-06-0 Copyright by Liber Pro Arte Editor Liber Pro Arte ul. Długa 26/28 00-950 Warsaw CONTENTS Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska Preface 7 Reinhard Strohm The Wanderings of Music through Space and Time 17 Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Eighteenth-Century Warsaw: Periphery, Keystone, (and) Centre of European Musical Culture 33 Harry White ‘Attending His Majesty’s State in Ireland’: English, German and Italian Musicians in Dublin, 1700–1762 53 Berthold Over Düsseldorf – Zweibrücken – Munich. Musicians’ Migrations in the Wittelsbach Dynasty 65 Gesa zur Nieden Music and the Establishment of French Huguenots in Northern Germany during the Eighteenth Century 87 Szymon Paczkowski Christoph August von Wackerbarth (1662–1734) and His ‘Cammer-Musique’ 109 Vjera Katalinić Giovanni Giornovichi / Ivan Jarnović in Stockholm: A Centre or a Periphery? 127 Katarina Trček Marušič Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Migration Flows in the Territory of Today’s Slovenia 139 Maja Milošević From the Periphery to the Centre and Back: The Case of Giuseppe Raffaelli (1767–1843) from Hvar 151 Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska Music Repertory in the Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania. -

09 March 2020

09 March 2020 12:01 AM Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) Der Freischutz (Overture) Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Kenneth Montgomery (conductor) NLNOS 12:11 AM George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Suite No 2 in F major HWV 427 Christian Ihle Hadland (piano) GBBBC 12:20 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) 4 Schemelli Chorales (BWV.478, 484, 492 and 502) Bernarda Fink (mezzo soprano), Marco Fink (bass baritone), Domen Marincic (gamba), Dalibor Miklavcic (organ) SIRTVS 12:30 AM Ture Rangstrom (1884-1947) Suite for violin and piano No 1 'In modo antico' Tale Olsson (violin), Mats Jansson (piano) SESR 12:39 AM Nicolaas Arie Bouwman (1854-1941) Thalia - overture for wind orchestra (1888) Dutch National Youth Wind Orchestra, Jan Cober (conductor) NLNOS 12:47 AM Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Sonata in D minor Fugue (K.41); Presto (K. 18) Eduardo Lopez Banzo (harpsichord) PLPR 12:57 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Trio for viola, cello and piano (Op.114) in A minor Maxim Rysanov (viola), Ekaterina Apekisheva (piano), Kristina Blaumane (cello) GBBBC 01:23 AM Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) Lyric pieces - book 1 for piano Op 12 Zoltan Kocsis (piano) HUMR 01:35 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) Flute Concerto in G major (Wq 169) Tom Ottar Andreassen (flute), Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Roy Goodman (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto in D, RV 562 (Andante, Allegro) Les Concert des Nations, Jordi Savall (conductor) ESCAT 02:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Violin Concerto in D, RV 230 'L'estro armonico' (Larghetto) -

John Kitchen Plays Handel Overtures on the 1755 Kirckman Harpsichord from the Raymond Russell Collection GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759): OVERTURES & SUITES

John Kitchen plays Handel Overtures on the 1755 Kirckman harpsichord from the Raymond Russell Collection GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759): OVERTURES & SUITES Overture to the Occasional Oratorio Suite in G (HWV 450) 1 [Largo] [1:14] 22 Preludio [2:27] 2 Allegro [2:35] 23 Allemande [2:21] 3 Adagio – [1:56] 24 Courante [1:52] 4 March [1:51] 25 Sarabande [3:23] 26 Gigue [0:58] Overture to Athalia 27 Menuet [1:05] 5 Allegro [2:35] 6 Grave – [0:47] Overture to Il Pastor Fido 7 Allegro [2:23] 28 Largo – [1:18] 29 Allegro [2:16] Overture to Radamisto 30 A tempo di Bourrée [1:59] 8 Largo – [1:11] 9 Allegro [2:01] Overture to Teseo 31 Largo – [1:30] Suite in A (HWV 454) 32 Allegro – [1:20] 10 Allemande [5:48] 33 Lentement – [0:35] 11 Courante [3:25] 34 Allegro [1:52] 12 Sarabande [2:22] 13 Gigue [2:55] Overture to Rinaldo 35 Largo – [1:10] Overture to Samson 36 Allegro [3:08] 14 Andante – [3:17] 37 Adagio – [0:55] 15 Adagio – [0:11] 38 Giga, presto [1:22] 16 Allegro [1:47] 17 Minuet [2:20] Total playing time [79:50] Overture to Saul 18 Allegro [4:27] Recorded on 17-18 December 2008 Image (p2): MS excerpt from William Babell’s Delphian Records – Edinburgh – UK 19 Larghetto [2:01] at St Cecilia’s Hall, Edinburgh transcription of Rinaldo www.delphianrecords.co.uk Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter Photography: Raymond Parks 20 [2:54] Allegro 24-bit digital editing & mastering: Paul Baxter Design: Drew Padrutt With thanks to the University of Edinburgh 21 Andante larghetto [minuet] [1:59] Instrument preparation: John Raymond Booklet editor: John Fallas -

Strauss | Staatskapelle Weimar & Kirill Karabits

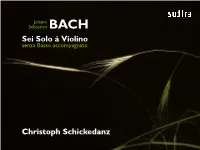

Johann Sebastian BACH Sei Solo á Violino senza Basso accompagnato Christoph Schickedanz Sonata No. 1 in G minor, BWV 1001 Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004 I. Adagio 3:43 I. Allemanda 4:59 II. Fuga. Allegro 4:35 II. Corrente 2:33 III. Siciliana 2:41 III. Sarabanda 3:46 IV. Presto 3:14 IV. Giga 3:42 V. Ciaccona 12:55 Partita No. 1 in B minor, BWV 1002 I. Allemanda 5:09 – Sonata No. 3 in C major, BWV 1005 Double 2:39 I. Adagio 3:43 II. Corrente 3:09 – II. Fuga 9:40 Double. Presto 2:59 III. Largo 2:46 III. Sarabande 3:30 – IV. Allegro assai 5:09 Double 2:34 IV. Tempo di Borea 2:55 – Partita No. 3 in E major, BWV 1006 Double 2:59 I. Preludio 3:26 II. Loure 3:39 Sonata No. 2 in A minor, BWV 1003 III. Gavotte en Rondeau 2:39 I. Grave 4:25 IV. Menuet I 1:50 II. Fuga 7:22 V. Menuet II 1:42 III. Andante 4:23 VI. Bourée 1:28 IV. Allegro 5:56 VII. Gigue 1:53 A new horizon, beyond time Yehudi Menuhin referred to the six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin by Johann Sebastian Bach as the “Old Testament for violinists”. Indeed this comparison describes very accurately the high rank that this extraordinary work has assumed in the history of the violin. Transcending genre, it is regarded as a shrine of Western music history, as a miracle of musical timelessness and expressive depth. -

Voir Le Livret (Pdf)

Londoncirca 1720 Corelli’s Legacy FRANZ LISZT JOHANN CHRISTIAN SCHICKHARDT London circa 1720 Concerto II op. 19 for 2 recorders, 2 traversos [orig. 4 recorders] and basso continuo Transp. to A minor / La mineur Corelli’s Legacy / L’héritage de Corelli (Amsterdam, nd, 1712-15 Etienne Roger & Michel Charles Le Cene) 16 | Allegro 2’13 WILLIAM BABELL (c. 1690-1723) 17 | Adagio 4’02 Concerto II op. 3 for sixth flute 18 | Vivace 1’39 D major / Ré majeur (London, 1730, John Walsh) 19 | Allegro 1’59 1 | Adagio - Allegro 2’11 2 | Adagio 3’02 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 3 | Allegro 3’13 Sonata per la viola da gamba HWV 364b G minor / Sol mineur FRANCESCO GEMINIANI (1687-1762) (Londres c. 1730, John Walsh / Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, Mu. MS 261) Sonata IV op. 1, H. 4 20 | Andante larghetto 2’04 D major / Ré majeur 21 | Allegro 1’58 (London, 1716 / London 1718, Richard Meares / London, 1719, John Walsh / Amsterdam, 1719, Jeanne Roger) 22 | Adagio 0’47 4 | Adagio 1’47 23 | Allegro 2’19 5 | Allegro 2’30 6 | Grave 1’07 24 | Spera si mio caro bene 7’15 7 | Allegro 1’41 Aria in B minor, arr. from Admeto HWV 22, opera, 1727 (Handel’s Select aires or Sonatas […], collected from all the late Operas. Londres, nd, 1738 ou 1743, John Walsh) ARCANGELO CORELLI (1653-1713) arranged by JOHANN CHRISTIAN SCHICKHARDT (c. 1681-1762) Sonata IV op. 6 after / d’après les Concerti grossi nos. 1 & 2 op. 6 NICOLA FRANCESCO HAYM (1678-1729) arr. PIETRO CHABOUD (fl. -

Judas Maccabaeus HWV 63

George Frideric HANDEL Judas Maccabaeus HWV 63 Soli SMsTB, Coro S(S)ATB 2 Flauti dolci, 2 Flauti, 2 Oboi, 2 Fagotti 2 Corni, 3 Trombe, Timpani, (Tamburo militare) 2 (3) Violini, Viola e Basso continuo (Violoncello, Contrabbasso, Cembalo/Organo) herausgegeben von/edited by Felix Loy Stuttgart Handel Editions Urtext Partitur/Full score C Carus 55.063 Inhalt /Contents Vorwort IV Foreword IX First Part 1. Ouverture 1 2. Chorus Mourn, ye afflicted children / Klagt, Söhne Judas 9 3. Recitative (Israelitish Woman, Isr. Man) Well may your sorrows / Ja, Brüder! klagt 16 4. Duet (Isr. Woman, Isr. Man) From this dread scene / Der stolzen Macht 17 5. Chorus For Sion lamentation make / Wir weihn dem Edlen Klag’ und Schmerz 22 *6. Recitative (Isr. Man) Not vain is all this storm of grief / Nicht ganz umsonst ist eure Klage 26 7. Air (Isr. Woman) Pious orgies / Fromme Tränen 27 8. Chorus O Father, whose almighty pow’r / Du Gott, dem Erd und Himmel schweigt 29 9. Accompagnato (Simon) I feel the Deity within / Vernehmt! die Gottheit spricht durch mich 36 10. Air (Simon) and Chorus Arm, arm, ye brave / Auf! Heer des Herrn 37 Chorus We come in bright array / Wohlan! wir folgen gern 42 11. Recitative (Judas Maccabaeus) ’Tis well, my friends / Wie sehr, o Volk 47 12. Air (Judas Maccabaeus) Call forth thy pow’rs / Bewaffne dich 48 13. Recitative (Isr. Woman) To heav’n’s immortal King / Wir wenden uns zu Gott 51 *14. Air (Isr. Woman) O liberty / Ohne dich, du goldne Freiheit! 51 15. Air (Isr. -

Historic Organs of Belgium May 15-26, 2018 12 Days with J

historic organs of BELGIUM May 15-26, 2018 12 Days with J. Michael Barone www.americanpublicmedia.org www.pipedreams.org National broadcasts of Pipedreams are made possible with funding from Mr. & Mrs. Wesley C. Dudley, grants from Walter McCarthy, Clara Ueland, and the Greystone Foundation, the Art and Martha Kaemmer Fund of the HRK Foundation, and Jan Kirchner on behalf of her family foun- dation, by the contributions of listeners to American Public Media stations nationwide, and by the thirty member organizations of the Associated Pipe Organ Builders of America, APOBA, represent- ing the designers and creators of pipe organs heard throughout the country and around the world, with information at www.apoba.com. See and hear Pipedreams on the Internet 24-7 at www.pipedreams.org. A complete booklet pdf with the tour itinerary can be accessed online at www.pipedreams.org/tour Table of Contents Welcome Letter Page 2 Bios of Hosts and Organists Page 3-6 A History of Organs in Belgium Page 7-12 Alphabetical List of Organ Builders Page 13-17 Organ Observations Page 18-21 Tour Itinerary Page 22-25 Playing the Organs Page 26 Organ Sites Page 27-124 Rooming List Page 125 Traveler Profiles Page 126-139 Hotel List Page 130-131 Map Inside Back Cover Thanks to the following people for their valuable assistance in creating this tour: Rachel Perfecto and Paul De Maeyer Valerie Bartl, Cynthia Jorgenson, Kristin Sullivan, Janet Tollund, and Tom Witt of Accolades International Tours for the Arts in Minneapolis. In addition to site specific websites, we gratefully acknowledge the following source for this booklet: http://www.orgbase.nl PAGE 22 HISTORICALORGANTOUR OBSERVATIONS DISCOGRAPHYBACKGROUNDWELCOME ITINERARYHOSTS Welcome Letter from Michael..