Ladakhi Knowledge and Western Learning: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photographic Archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus

Photographic archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Photographic archives in Paris and London. European bulletin of Himalayan research, University of Cambridge ; Südasien-Institut (Heidelberg, Allemagne)., 1999, Special double issue on photography dedicated to Corneille Jest, pp.103-106. hal-00586763 HAL Id: hal-00586763 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00586763 Submitted on 10 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EBHR 15- 16. 1998- 1999 PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES IN PARIS AND epal among the Limbu. Rai. Chetri. Sherpa, Bhotiya and Sunuwar. LONDO ' Both these collections encompa'\s pictures of land flY PA CALE DOLL FUSS scapes. architecture. techniques. agriculture. herding, lrade, feslivals. shaman practices. rites or passage. etc. In addition to these major collecti ons. once can find I. PUOTOGRAPfIIC ARCIUVES IN PARIS 350 photographs taken in 1965 by Jaeques Millot. (director of the RCP epal) in the Kathmandu Valley. Photographic Library ("Phototheque"), Musee de approx. 110 photographs (c. 1966-67) by Mireille Helf /'lIommc. fer. related primari Iy to musicians caSles, 45 photo 1'1. du Trocadero. Paris 750 16. graphs (1967-68) by Marc Gaborieau. -

Existing Tourism Infrastructure and Services in Lahaul Valley of Himachal Pradesh: a Case Study of Hotels / Guest Houses, Home Stays and Travel Agencies

Amity Research Journal of Tourism, Aviation and Hospitality Vol. 01, issue 01, January-June 2016 Existing Tourism Infrastructure and Services in Lahaul Valley of Himachal Pradesh: A Case Study of Hotels / Guest Houses, Home Stays and Travel Agencies Dr. Arvind Kumar Project Fellow-UGC-SAP DRS Level-I (Tourism), Institute of Vocational (Tourism) Studies, Himachal Pradesh University, Summer Hill, Shimla (H.P.) PIN-171005, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The district has occupied an area of Lahaul valley of Himachal Pradesh is one of approximately 3979 metres. The district has the geographically restricted valleys of India. been divided into two division i.e. Lahaul and It remains blocked by Rohtang pass (approx. Spiti. The Lahaul valley is popular among 3979 metres) during winters for almost six adventure tourists during summers and months. During remaining six months tourists monsoon season in India. Geographically, it is make their passage to different tourist places one of the beautiful valleys of the country. It is in Lahaul up to Leh in Jammu and Kashmir. home to numerous tourist attractions like Their passage is assisted by tourist Chnadra and Bhaga rivers, their collision at a infrastructure and services available within the place namely Tandi, Udaipur, Miyar village, valley. The research study has utilized Trilokinath village, Keylong, Guru Ghantal secondary information obtained from office of Monastery, Jispa, Zanskar Sumdo, Shingola deputy director of tourism and civil aviation, pass, Patseo, Baralacha pass, Sarchu, Sissu, Kullu at Manali to assess the existing tourism Koksar and Lady of Keylong glacier etc. Due infrastructure and services within the valley. -

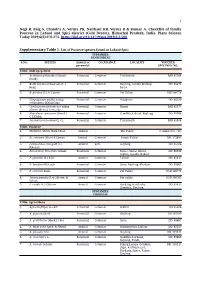

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of Family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti Distr

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti district (Cold Desert), Himachal Pradesh, India. Plant Science Today 2019;6(2):270-274. https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.2019.6.2.500 Supplementary Table 1. List of Poaceae species found in Lahaul-Spiti SUBFAMILY: PANICOIDEAE S.No. SPECIES Annual or OCCURANCE LOCALITY VOUCHER perennial SPECIMEN NO. Tribe- Andropogoneae 1. Arthraxon prionodes (Steud.) Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45386 Dandy 2. Bothriochloa ischaemum (L.) Perennial Common Keylong, Gondla, Kailing- DD 85472 Keng ka-Jot 3. B. pertusa (L.) A. Camus Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD100754 4. Chrysopogon gryllus subsp. Perennial Common Madgram DD 85320 echinulatus (Nees) Cope 5. Cymbopogon jwarancusa subsp. Perennial Common Kamri BSD 45377 olivieri (Boiss.) Soenarko 6. Phacelurus speciosus (Steud.) Perennial Common Gondhla, Lahaul, Keylong DD 99908 C.E.Hubb. 7. Saccharum ravennae (L.) L. Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45958 Tribe- Paniceae 1. Digitaria ciliaris (Retz.) Koel Annual - Pin Valley C. Sekar (loc. cit.) 2. D. cruciata (Nees) A.Camus Annual Common Pattan Valley DD 172693 3. Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Annual Rare Keylong DD 85186 P.Beauv. 4. Pennisetum flaccidum Griseb. Perennial Common Sissoo, Sanao, Khote, DD 85530 Gojina, Gondla, Koksar 5. P. glaucum (L.) R.Br. Annual Common Lahaul DD 85417 6. P. lanatum Klotzsch Perennial Common Sissu, Keylong, Khoksar DD 99862 7. P. orientale Rich. Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD 100775 8. Setaria pumila (Poir.) Roem. & Annual Common Pin valley BSD 100763 Schult. 9. S. viridis (L.) P.Beauv. Annual Common Kardang, Baralacha, DD 85415 Gondhla, Keylong SUBFAMILY: POOIDEAE Tribe- Agrostideae 1. -

Sub- State Site Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (Lahaul & Spiti and Kinnaur)

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY SUB- STATE SITE BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN (LAHAUL & SPITI AND KINNAUR) MAY-2002 SUBMITTED TO: TPCG (NBSAP), MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT & FOREST,GOI, NEW DELHI, TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT, H.P. SECRETARIAT, SHIMLA-2 & STATE COUNCIL FOR SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT, 34 SDA COMPLEX, KASUMPTI, SHIMLA –9 CONTENTS S. No. Chapter Pages 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Profile of Area 7-16 3. Current Range and Status of Biodiversity 17-35 4. Statement of the problems relating to 36-38 biodiversity 5. Major Actors and their current roles relevant 39-40 to biodiversity 6. Ongoing biodiversity- related initiatives 41-46 (including assessment of their efficacy) 7. Gap Analysis 47-48 8. Major strategies to fill these gaps and to 49-51 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 9. Required actions to fill gaps, and 52-61 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 10. Proposed Projects for Implementation of 62-74 Action Plan 11. Comprehensive Note 75-81 12. Public Hearing 82-86 13. Synthesis of the Issues/problems 87-96 14. Bibliography 97-99 Annexures CHAPTER- 1 INTRODUCTION Biodiversity or Biological Diversity is the variability within and between all microorganisms, plants and animals and the ecological system, which they inhabit. It starts with genes and manifests itself as organisms, populations, species and communities, which give life to ecosystems, landscapes and ultimately the biosphere (Swaminathan, 1997). India in general and Himalayas in particular are the reservoir of genetic wealth ranging from tropical, sub-tropical, sub temperate including dry temperate and cold desert culminating into alpine (both dry and moist) flora and fauna. -

Approved Capex Budget 2020-21 Final

Capex Budget 2020-21 of Leh District I NDEX S. No Sector Page No. S. No Sector Page No. 1 2 3 1 2 3 GN-0 3 29 Forest 56 - 57 GN-1 4 - 5 30 Parks & Garden 58 1 Agriculture 6 - 9 31 Command Area Dev. 59 - 60 2 Animal Husbandry 10 - 13 32 Power 61 - 62 3 Fisheries 14 33 CA&PDS 63 - 64 4 Horticulture 15 - 16 34 Soil Conservation 65 5 Wildlife 17 35 Settlement 66 6 DIC 18 36 Govt. Polytechnic College 67 7 Handloom 19 - 20 37 Labour Welfare 68 8 Tourism 21 38 Public Works Department 9 Arts & Culture 22 1 Transport & Communication 69 - 85 10 ITI 23 2 Urban Development 86 - 87 11 Local Bodies 24 3 Housing Rental 88 12 Social Welfare 25 4 Non Functional Building 89 - 90 13 Evaluation & Statistics 26 5 PHE 97 - 92 14 District Motor Garages 27 6 Minor Irrigation 93 - 95 15 EJM Degree College 28 7 Flood Control 96 - 99 16 CCDF 29 8 Medium Irrigation 100 17 Employment 30 9 Mechanical Division 101 18 Information Technology 31 Rural Development Deptt. 19 Youth Services & Sports 32 1 Community Development 102 - 138 20 Non Conventional Energy 33 OTHERS 21 Sheep Husbandry 34 - 36 1 Untied 139 22 Information 37 2 IAY 139 23 Health 38 - 42 3 MGNREGA 139 24 Planning Mechinery 43 4 Rural Sanitation 139 25 Cooperatives 44 - 45 5 SSA 139 26 Handicraft 46 6 RMSA 139 27 Education 47 - 53 7 AIBP 139 28 ICDS 54 - 55 8 MsDP 139 CAPEX BUDGET 2020-21 OF LEH DISTRICT (statement GN 0) (Rs. -

No Longer Tracking Greenery in High Altitudes: Pastoral Practices of Rupshu Nomads and Their Implications for Biodiversity Conse

Singh et al. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice 2013, 3:16 http://www.pastoralismjournal.com/content/3/1/16 RESEARCH Open Access No longer tracking greenery in high altitudes: Pastoral practices of Rupshu nomads and their implications for biodiversity conservation Navinder J Singh1,2,3*, Yash Veer Bhatnagar2, Nicolas Lecomte4, Joseph L Fox1 and Nigel G Yoccoz1 Abstract Nomadic pastoralism has thrived in Asia’s rangelands for several millennia by tracking seasonal changes in forage productivity and coping with a harsh climate. This pastoralist lifestyle, however, has come under intense transformations in recent decades due to socio-political and land use changes. One example is of the high-altitude trans-Himalayan rangelands of the Jammu and Kashmir State in northern India: major socio-political reorganisation over the last five decades has significantly impacted the traditional pasture use pattern and resources. We outline the organizational transformations and movement patterns of the Rupshu pastoralists who inhabit the region. We demonstrate the changes in terms of intensification of pasture use across the region as well as a social reorganisation due to accommodation of Tibetan refugees following the Sino-Indian war in 1961 to 1962. We focus in particular on the Tso Kar basin - an important socio-ecological system of livestock herding and biodiversity in the eastern Ladakh region. The post-war developmental policies of the government have contributed to these modifications in traditional pasture use and present a threat to the rangelands as well as to the local biodiversity. In the Tso Kar basin, the number of households and livestock has almost doubled while pasture area has declined by half. -

2000 Ladakh and Zanskar-The Land of Passes

1 LADAKH AND ZANSKAR -THE LAND OF PASSES The great mountains are quick to kill or maim when mistakes are made. Surely, a safe descent is as much a part of the climb as “getting to the top”. Dead men are successful only when they have given their lives for others. Kenneth Mason, Abode of Snow (p. 289) The remote and isolated region of Ladakh lies in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, marking the western limit of the spread of Tibetan culture. Before it became a part of India in the 1834, when the rulers of Jammu brought it under their control, Ladakh was an independent kingdom closely linked with Tibet, its strong Buddhist culture and its various gompas (monasteries) such as Lamayuru, Alchi and Thiksey a living testimony to this fact. One of the most prominent monuments is the towering palace in Leh, built by the Ladakhi ruler, Singe Namgyal (c. 1570 to 1642). Ladakh’s inhospitable terrain has seen enough traders, missionaries and invading armies to justify the Ladakhi saying: “The land is so barren and the passes are so high that only the best of friends or worst of enemies would want to visit us.” The elevation of Ladakh gives it an extreme climate; burning heat by day and freezing cold at night. Due to the rarefied atmosphere, the sun’s rays heat the ground quickly, the dry air allowing for quick cooling, leading to sub-zero temperatures at night. Lying in the rain- shadow of the Great Himalaya, this arid, bare region receives scanty rainfall, and its primary source of water is the winter snowfall. -

Cartes De Trekking LADAKH & ZANSKAR Trekking Maps

Cartes de trekking LADAKH & ZANSKAR Trekking Maps Index des noms de lieux Index of place names NORTH CENTER SOUTH abram pointet www.abram.ch Ladakh & Zanskar Cartes de trekking / Trekking Maps Editions Olizane A Arvat E 27 Bhardas La C 18 Burma P 11 Abadon B 1 Arzu N 11 Bhator D 24 Burshung O 19 Abale O 5 Arzu N 11 Bhutna A 19 C Abran … Abrang Arzu Lha Khang N 11 Biachuthasa A 7 Cerro Kishtwar C 19 Abrang C 16 Ashur Togpo H 8 Biachuthusa … Biachuthasa Cha H 20 Abuntse D 7 Askuta F 11 Biadangdo G 3 Cha H 20 Achina Lungba D 6 Askuta Togpo F 11 Biagdang Gl. G 2 Cha Gonpa H 20 Achina Lungba Gonpa D 6 Ating E 17 Biama … Beama Chacha Got C 26 Achina Thang C 7 Ayi K 3 Biar Malera A 24 Chacham Togpo K 14 Achina Thang Gonpa D 7 Ayu M 11 Biarsak F 2 Chachatapsa D 7 Achinatung … Achina Thang B Bibcha F 19 Chagangle V 24 Achirik I 11 Bagioth F 27 Bibcha Lha Khang F 19 Chagar Tso S 12 Achirik Lha Khang I 11 Bahai Nala B 22 Bidrabani Sarai A 22 Chagarchan La U 24 Agcho C 15 Baihali Jot C 25 Bilargu D 5 Chagdo W 9 Agham O 8 Bakartse C 16 Billing Nala G 27 Chaghacha E 9 Agsho B 17 Bakula Bao I 13 Bima E 27 Chaglung C 7 Agsho Gl. B 17 Baldar Gl. B 13 Birshungle V 26 Chagra U 11 Agsho La B 17 Baldes B 5 Bishitao A 22 Chagra U 11 Agyasol A 19 Baleli Jot E 22 Bishur B 25 Chagri F 9 Ajangliung J 7 Balhai Nala C 25 Bod Kharbu C 8 Chagtsang M 15 Akeke R 18 Balthal Got C 26 Bog I 27 Chagtsang La M 15 Akling L 11 Bangche Togpo G 15 Bokakphule V 27 Chakharung B 5 Aksaï Chin V 10 Bangche Togpo F 14 Boksar Gongma F 13 Chakrate T 16 Alam H 12 Bangongsho X 16 Boksar Yokma G 13 Chali Gali E 27 Alchi I 10 Banku G 8 Bolam L 11 Chaluk J 13 Alchi H 10 Banon D 23 Bong La M 21 Chalung U 21 Alchi Brok H 10 Banraj Gl. -

The Social Context of Nature Conservation in Nepal 25 Michael Kollmair, Ulrike Müller-Böker and Reto Soliva

24 Spring 2003 EBHR EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH European Bulletin of Himalayan Research The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is a product of collaboration and edited on a rotating basis between France (CNRS), Germany (South Asia Institute) and the UK (SOAS). Since October 2002 onwards, the German editorship has been run as a collective, presently including William S. Sax (managing editor), Martin Gaenszle, Elvira Graner, András Höfer, Axel Michaels, Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, Mona Schrempf and Claus Peter Zoller. We take the Himalayas to mean, the Karakorum, Hindukush, Ladakh, southern Tibet, Kashmir, north-west India, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and north-east India. The subjects we cover range from geography and economics to anthropology, sociology, philology, history, art history, and history of religions. In addition to scholarly articles, we publish book reviews, reports on research projects, information on Himalayan archives, news of forthcoming conferences, and funding opportunities. Manuscripts submitted are subject to a process of peer- review. Address for correspondence and submissions: European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, c/o Dept. of Anthropology South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg / Germany e-mail: [email protected]; fax: (+49) 6221 54 8898 For subscription details (and downloadable subscription forms), see our website: http://ebhr.sai.uni-heidelberg.de or contact by e-mail: [email protected] Contributing editors: France: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, Pascale Dollfus, Anne de Sales Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UPR 299 7, rue Guy Môquet 94801 Villejuif cedex France e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain: Michael Hutt, David Gellner, Ben Campbell School of Oriental and African Studies Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square London WC1H 0XG U.K. -

Demographic Structure of Ethnic Tribes in Cold Desert Leh Â

P: ISSN No. 2231-0045 RNI No. UPBIL/2012/55438 VOL.-7, ISSUE-2, November-2018 E: ISSN No. 2349-9435 Periodic Research Demographic Structure of Ethnic Tribes in Cold Desert Leh – Ladakh Abstract The present study was carried out on demographic structure of cold desert Leh- Ladakh. The analysis of the data reveals that the study area has a total population of 1, 33,487. Near about 77.49 percent of total population is a tribal population and is unevenly distributed. The major tribes are Bhots, Champas, Brokpas, Mons and Arghuns. The average physiological density of population is 260 persons / Km2. The overall literacy rate is 70.24 percent and varies among males and females. The average sex ratio is 690 females per thousand males that is less than the national average sex ratio of 943 females per thousand males. Majority of the population was engaged in secondary activities (45.72 %). Birth rate and death rate shows fluctuations with years and G. M. Rather there is declining trend in population growth from 1981 onwards. Sr. Assistant Professor Keywords: Demographic Structure, Tribal Population, Cold Desert Leh, Deptt.of Geography and Regional Physiological Density, Sex Ratio. Development, Introduction University of Kashmir, Population is defined as any finite or infinite collection of individual Srinagar, India objects. But in geography it refers to a congregation of human individual objects. The specialized study of population geography, began in early sixties with the presidential address delivered by Trewartha (Trewartha , 1953). Review of Literature According to Trewartha the scope of the field should include a treatment of all the variables present in the census schedule of advanced nation. -

Études Mongoles Et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques Et Tibétaines, 51 | 2020 “Fertilissimi Sunt Auri Dardae, Setae Vero Et Argenti”

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 51 | 2020 Ladakh Through the Ages. A Volume on Art History and Archaeology, followed by Varia “Fertilissimi sunt auri Dardae, setae vero et argenti”. Notes on some ancient open-air gold mining sites in Ladakh « Fertilissimi sunt auri Dardae, setae vero et argenti ». Note sur quelques anciennes mines d’or à ciel ouvert du Ladakh Martin Vernier Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4647 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.4647 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Martin Vernier, ““Fertilissimi sunt auri Dardae, setae vero et argenti”. Notes on some ancient open-air gold mining sites in Ladakh”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 51 | 2020, Online since 09 December 2020, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ emscat/4647 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/emscat.4647 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés “Fertilissimi sunt auri Dardae, setae vero et argenti”. Notes on some ancient... 1 “Fertilissimi sunt auri Dardae, setae vero et argenti”. Notes on some ancient open-air gold mining sites in Ladakh « Fertilissimi sunt auri Dardae, setae vero et argenti ». Note sur quelques anciennes mines d’or à ciel ouvert du Ladakh Martin Vernier Introduction 1 Gold-digging ants are part of the antique bestiary. About the size of a dog, they are reported to dig up gold from sandy areas. Herodotus (c. 484-c. 425 B.C.E.) located them in northern India1. The Greek historian didn’t claim first-hand information and was only quoting other travellers’ sayings of the time. -

Itinerary: Day 01: Delhi/Manali (560 Kms/12 Hrs)-Over Night at Volvo Bus

Itinerary: Day 01: Delhi/Manali (560 kms/12 hrs)-Over night at Volvo bus. Day 02: In Manal-city tour Day 03: Manali/ Rohtang Pass/ Keylong/Jispa (140 kms/ 8 hrs) Day 04: Jispa/ Baralacha Pass/ Sarchu (100 kms/ 7 hrs) Day 05: Sarchu/ Leh (253 kms/ 10 hrs) Day 06: Leh/ Nubra Day 07: Nubra/ Leh Day 08: Leh/ Pangong Lake (160 kms/ 6-7 hrs) Day 09: Pangong/ Leh Day 10: Leh/Sarchu Day 11: Sarchu/ Manali/ (232 kms/10 hrs) Day 12: Depart Manali-over night at Volvo bus PACKAGE INCLUSION Accommodation in hotels/camps/guest house on twin/triple sharing basis as per package option. Check in/ out time is 12 noon MAP basis in hotel (Room+Breakfast+Dinner) starting with dinner in Manali till Breakfast on departure from Manali One Enfield bike (without fuel) (350 cc) per rider and as per the above itinerary Basic spares parts for the bike (any damage/ change of spares payable as extra directly) Accompanied guide one Motorbike Mechanic for the entire tour in bike Inner line Permit (camera fee not included) Volvo tickets from Delhi to Manali and Manali to Delhi Presently applicable taxes Local cuisine Interaction with local people Life time memories Bone fire on departure Gift items on departure from Manali Cost Exclusions : Any airfare/ train fare, Fuel for Bike Entrances to place of visit Any other meal than mentioned in itinerary Any personal or travel Insurance, tips, gratuities, portage, laundry, telephone calls, table drinks or any other expenses of personal nature, any item not specified under cost inclusions.