Brill's Tibetan Studies Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Dominique Townsend All rights reserved ABSTRACT Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend This dissertation investigates the relationships between Buddhism and culture as exemplified at Mindroling Monastery. Focusing on the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, I argue that Mindroling was a seminal religio-cultural institution that played a key role in cultivating the ruling elite class during a critical moment of Tibet’s history. This analysis demonstrates that the connections between Buddhism and high culture have been salient throughout the history of Buddhism, rendering the project relevant to a broad range of fields within Asian Studies and the Study of Religion. As the first extensive Western-language study of Mindroling, this project employs an interdisciplinary methodology combining historical, sociological, cultural and religious studies, and makes use of diverse Tibetan sources. Mindroling was founded in 1676 with ties to Tibet’s nobility and the Fifth Dalai Lama’s newly centralized government. It was a center for elite education until the twentieth century, and in this regard it was comparable to a Western university where young members of the nobility spent two to four years training in the arts and sciences and being shaped for positions of authority. This comparison serves to highlight commonalities between distant and familiar educational models and undercuts the tendency to diminish Tibetan culture to an exoticized imagining of Buddhism as a purely ascetic, world renouncing tradition. -

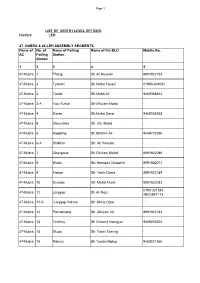

Final BLO,2012-13

Page 1 LIST OF BOOTH LEVEL OFFICER . District: LEH 47- NUBRA & 48-LEH ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS. Name of No. of Name of Polling Name of the BLO Mobile.No. AC Polling Station Station 1 3 3 4 5 47-Nubra 1 Thang Sh.Ali Hussain 8991922153 47-Nubra 2 Tyakshi Sh.Mohd Yousuf 01980-248031 47-Nubra 3 Turtuk Sh.Mohd Ali 9469368812 47-Nubra 3-A Youl Turtuk Sh:Ghulam Mohd - 47-Nubra 4 Garari Sh.Mohd Omar 9469265938 47-Nubra 5 Chulunkha Sh: Gh. Mohd - 47-Nubra 6 Bogdang Sh.Ibrahim Ali 9469732596 47-Nubra 6-A Shilkhor Sh: Ali Hassain - 47-Nubra 7 Changmar Sh.Ghulam Mehdi 8991922086 47-Nubra 8 Waris Sh: Namgail Chosphel 8991922073 47-Nubra 9 Fastan Sh: Tashi Dawa 8991922149 47-Nubra 10 Sunudo Sh: Mohd Anvar 8991922082 0190-221344 47-Nubra 11 Largyap Sh Ali Rozi /9622957173 47-Nubra 11-A Largyap Yokma Sh: Nima Otzer - 47-Nubra 12 Pachathang Sh. Ghulam Ali 8991922182 47-Nubra 13 Terchey Sh Chemet Namgyal 9469266204 47-Nubra 14 Skuru Sh; Tashi Tsering - 47-Nubra 15 Rakuru Sh Tsetan Motup 9469221366 Page 2 47-Nubra 16 Udamaru Sh:Mohd Ali 8991922151 47-Nubra 16-A Shukur Sh: Sonam Tashi - 47-Nubra 17 Hunderi Sh: Tashi Nurbu 8991922110 47-Nubra 18 Hunder Sh Ghulam Hussain 9469177470 47-Nubra 19 Hundar Dok Sh Phunchok Angchok 9469221358 47-Nubra 20 Skampuk Sh: Lobzang Thokmed - 47-Nubra 21 Partapur Smt. Sari Bano - 47-Nubra 22 Diskit Sh: Tsering Stobdan 01980-220011 47-Nubra 23 Burma Sh Tuskor Tagais 8991922100 47-Nubra 24 Charasa Sh Tsewang Stobgais 9469190201 47-Nubra 25 Kuri Sh: Padma Gurmat 9419885156 47-Nubra 26 Murgi Thukje Zangpo 9419851148 47-Nubra 27 Tongsted -

RET HS No. 1:RET Hors Série No. 1

Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines Table des Matières récapitulative des nos. 1-15 Hors-série numéro 01 — Août 2009 Table des Matières récapitulative des numéros 1-15 Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines Hors-série no. 1 — Août 2009 ISSN 1768-2959 Directeur : Jean-Luc Achard Comité de rédaction : Anne Chayet, Pierre Arènes, Jean-Luc Achard. Comité de lecture : Pierre Arènes (CNRS), Ester Bianchi (Dipartimento di Studi sull’Asia Orientale, Venezia), Anne Chayet (CNRS), Fabienne Jagou (EFEO), Rob Mayer (Oriental Institute, University of Oxford), Fernand Meyer (CNRS-EPHE), Fran- çoise Pommaret (CNRS), Ramon Prats (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona), Brigitte Steinman (Université de Lille) Jean-Luc Achard (CNRS). Périodicité La périodicité de la Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines est généralement bi-annuelle, les mois de parution étant, sauf indication contraire, Octobre et Avril. Les contributions doivent parvenir au moins deux (2) mois à l’avance. Les dates de proposition d’articles au co- mité de lecture sont Février pour une parution en Avril et Août pour une parution en Octobre. Participation La participation est ouverte aux membres statutaires des équipes CNRS, à leurs mem- bres associés, aux doctorants et aux chercheurs non-affiliés. Les articles et autres contributions sont proposées aux membres du comité de lec ture et sont soumis à l’approbation des membres du comité de rédaction. Les arti cles et autres contributions doivent être inédits ou leur ré-édition doit être justifiée et soumise à l’approbation des membres du comité de lecture. Les documents doivent parvenir sous la forme de fichiers Word (.doc exclusive- ment avec fontes unicodes), envoyés à l’adresse du directeur ([email protected]). -

Photographic Archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus

Photographic archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Photographic archives in Paris and London. European bulletin of Himalayan research, University of Cambridge ; Südasien-Institut (Heidelberg, Allemagne)., 1999, Special double issue on photography dedicated to Corneille Jest, pp.103-106. hal-00586763 HAL Id: hal-00586763 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00586763 Submitted on 10 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EBHR 15- 16. 1998- 1999 PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES IN PARIS AND epal among the Limbu. Rai. Chetri. Sherpa, Bhotiya and Sunuwar. LONDO ' Both these collections encompa'\s pictures of land flY PA CALE DOLL FUSS scapes. architecture. techniques. agriculture. herding, lrade, feslivals. shaman practices. rites or passage. etc. In addition to these major collecti ons. once can find I. PUOTOGRAPfIIC ARCIUVES IN PARIS 350 photographs taken in 1965 by Jaeques Millot. (director of the RCP epal) in the Kathmandu Valley. Photographic Library ("Phototheque"), Musee de approx. 110 photographs (c. 1966-67) by Mireille Helf /'lIommc. fer. related primari Iy to musicians caSles, 45 photo 1'1. du Trocadero. Paris 750 16. graphs (1967-68) by Marc Gaborieau. -

![Annualreport [2002] IIAS Reasearch: Programmes, Networks and Fellowships [ Section 2 |P 27]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8707/annualreport-2002-iias-reasearch-programmes-networks-and-fellowships-section-2-p-27-478707.webp)

Annualreport [2002] IIAS Reasearch: Programmes, Networks and Fellowships [ Section 2 |P 27]

Annualreport [2002] IIAS Reasearch: Programmes, Networks and Fellowships [ section 2 |p 27] Senior visiting fellows Visiting exchange fellows The IIAS offers (senior) scholars the possibility to engage in research The IIAS has signed several Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) with work in the Netherlands. The period varies from one to three months. foreign research institutes, thereby providing scholars with an opportunity to participate in international exchanges for a maximum Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere (Sri Lanka) period of one year. Foreign scholars can apply to be sent abroad to the Stationed at the Branch Office Amsterdam MoU partners of the IIAS. Co-sponsored by the ISIM Period: 1 July–3 November 2002 Dr HO Ming-Yu (Taiwan) Topic: Restudying the veddah: Buddhism, aboriginality, and Co-sponsored by NSC. primitivism in pre-colonial and post-colonial discourses. Period: 18 December 2002 – 18 June 2003 Topic: Law, foreign direct investment, and economic development Academic activities: in Taiwan 1992-2002 24 September, ‘On quartering and cannibalism and forms of anthropophagy’, lecture presented, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Prof. LIN Wei-Sheng (Taiwan) Co-sponsored by NSC Period: 9 October – 15 March 2003 Topic: Transformation of international trade in Taiwan under Dutch rule Dr TSENG Mei-Chiun (Taiwan) Co-sponsored by NSC. Period: 1 December 2002 – 1 March 2003 Topic: Costs of first-ever eschemic stroke in Taiwan. Academic activities: Two abstracts prepared for the 12th European Stroke Conference were accepted for poster presentation. (poster-number Management/Economics 8, and Risk Factors and Etiology 32, respectively). Following the conference submission, we completed the full papers and submitted them to the Stroke journal (http://stroke.ahajournals.org/) for publication consideration (manuscript #03-0177 and #03-0204). -

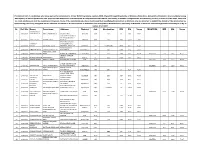

Approved Capex Budget 2020-21 Final

Capex Budget 2020-21 of Leh District I NDEX S. No Sector Page No. S. No Sector Page No. 1 2 3 1 2 3 GN-0 3 29 Forest 56 - 57 GN-1 4 - 5 30 Parks & Garden 58 1 Agriculture 6 - 9 31 Command Area Dev. 59 - 60 2 Animal Husbandry 10 - 13 32 Power 61 - 62 3 Fisheries 14 33 CA&PDS 63 - 64 4 Horticulture 15 - 16 34 Soil Conservation 65 5 Wildlife 17 35 Settlement 66 6 DIC 18 36 Govt. Polytechnic College 67 7 Handloom 19 - 20 37 Labour Welfare 68 8 Tourism 21 38 Public Works Department 9 Arts & Culture 22 1 Transport & Communication 69 - 85 10 ITI 23 2 Urban Development 86 - 87 11 Local Bodies 24 3 Housing Rental 88 12 Social Welfare 25 4 Non Functional Building 89 - 90 13 Evaluation & Statistics 26 5 PHE 97 - 92 14 District Motor Garages 27 6 Minor Irrigation 93 - 95 15 EJM Degree College 28 7 Flood Control 96 - 99 16 CCDF 29 8 Medium Irrigation 100 17 Employment 30 9 Mechanical Division 101 18 Information Technology 31 Rural Development Deptt. 19 Youth Services & Sports 32 1 Community Development 102 - 138 20 Non Conventional Energy 33 OTHERS 21 Sheep Husbandry 34 - 36 1 Untied 139 22 Information 37 2 IAY 139 23 Health 38 - 42 3 MGNREGA 139 24 Planning Mechinery 43 4 Rural Sanitation 139 25 Cooperatives 44 - 45 5 SSA 139 26 Handicraft 46 6 RMSA 139 27 Education 47 - 53 7 AIBP 139 28 ICDS 54 - 55 8 MsDP 139 CAPEX BUDGET 2020-21 OF LEH DISTRICT (statement GN 0) (Rs. -

Cartes De Trekking LADAKH & ZANSKAR Trekking Maps

Cartes de trekking LADAKH & ZANSKAR Trekking Maps Index des noms de lieux Index of place names NORTH CENTER SOUTH abram pointet www.abram.ch Ladakh & Zanskar Cartes de trekking / Trekking Maps Editions Olizane A Arvat E 27 Bhardas La C 18 Burma P 11 Abadon B 1 Arzu N 11 Bhator D 24 Burshung O 19 Abale O 5 Arzu N 11 Bhutna A 19 C Abran … Abrang Arzu Lha Khang N 11 Biachuthasa A 7 Cerro Kishtwar C 19 Abrang C 16 Ashur Togpo H 8 Biachuthusa … Biachuthasa Cha H 20 Abuntse D 7 Askuta F 11 Biadangdo G 3 Cha H 20 Achina Lungba D 6 Askuta Togpo F 11 Biagdang Gl. G 2 Cha Gonpa H 20 Achina Lungba Gonpa D 6 Ating E 17 Biama … Beama Chacha Got C 26 Achina Thang C 7 Ayi K 3 Biar Malera A 24 Chacham Togpo K 14 Achina Thang Gonpa D 7 Ayu M 11 Biarsak F 2 Chachatapsa D 7 Achinatung … Achina Thang B Bibcha F 19 Chagangle V 24 Achirik I 11 Bagioth F 27 Bibcha Lha Khang F 19 Chagar Tso S 12 Achirik Lha Khang I 11 Bahai Nala B 22 Bidrabani Sarai A 22 Chagarchan La U 24 Agcho C 15 Baihali Jot C 25 Bilargu D 5 Chagdo W 9 Agham O 8 Bakartse C 16 Billing Nala G 27 Chaghacha E 9 Agsho B 17 Bakula Bao I 13 Bima E 27 Chaglung C 7 Agsho Gl. B 17 Baldar Gl. B 13 Birshungle V 26 Chagra U 11 Agsho La B 17 Baldes B 5 Bishitao A 22 Chagra U 11 Agyasol A 19 Baleli Jot E 22 Bishur B 25 Chagri F 9 Ajangliung J 7 Balhai Nala C 25 Bod Kharbu C 8 Chagtsang M 15 Akeke R 18 Balthal Got C 26 Bog I 27 Chagtsang La M 15 Akling L 11 Bangche Togpo G 15 Bokakphule V 27 Chakharung B 5 Aksaï Chin V 10 Bangche Togpo F 14 Boksar Gongma F 13 Chakrate T 16 Alam H 12 Bangongsho X 16 Boksar Yokma G 13 Chali Gali E 27 Alchi I 10 Banku G 8 Bolam L 11 Chaluk J 13 Alchi H 10 Banon D 23 Bong La M 21 Chalung U 21 Alchi Brok H 10 Banraj Gl. -

The Social Context of Nature Conservation in Nepal 25 Michael Kollmair, Ulrike Müller-Böker and Reto Soliva

24 Spring 2003 EBHR EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH European Bulletin of Himalayan Research The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is a product of collaboration and edited on a rotating basis between France (CNRS), Germany (South Asia Institute) and the UK (SOAS). Since October 2002 onwards, the German editorship has been run as a collective, presently including William S. Sax (managing editor), Martin Gaenszle, Elvira Graner, András Höfer, Axel Michaels, Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, Mona Schrempf and Claus Peter Zoller. We take the Himalayas to mean, the Karakorum, Hindukush, Ladakh, southern Tibet, Kashmir, north-west India, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and north-east India. The subjects we cover range from geography and economics to anthropology, sociology, philology, history, art history, and history of religions. In addition to scholarly articles, we publish book reviews, reports on research projects, information on Himalayan archives, news of forthcoming conferences, and funding opportunities. Manuscripts submitted are subject to a process of peer- review. Address for correspondence and submissions: European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, c/o Dept. of Anthropology South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg / Germany e-mail: [email protected]; fax: (+49) 6221 54 8898 For subscription details (and downloadable subscription forms), see our website: http://ebhr.sai.uni-heidelberg.de or contact by e-mail: [email protected] Contributing editors: France: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, Pascale Dollfus, Anne de Sales Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UPR 299 7, rue Guy Môquet 94801 Villejuif cedex France e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain: Michael Hutt, David Gellner, Ben Campbell School of Oriental and African Studies Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square London WC1H 0XG U.K. -

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE of LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much Ofwhat Is Generally Considered to Represent the Earl

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE OF LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much ofwhat is generally considered to represent the earliest heritage of Ladakh cannot be securely dated. It even cannot be said with certainty when Buddhism reached Ladakh. Similarly, much ofwhat is recorded in inscriptions and texts concerning the period preceding the establishment of the Ladakhi kingdom in the late 151h century is either fragmentary or legendary. Thus, only a comparative study of these records together 'with the architectural and artistic heritage can provide more secure glimpses into the early history of Buddhism in Ladakh. This study outlines the most crucial historical issues and questions from the point of view of an art historian and archaeologist, drawing on a selection of exemplary monuments and o~jects, the historical value of which has in many instances yet to be exploited. vVithout aiming to be so comprehensive, the article updates the ground breaking work of A.H. Francke (particularly 1914, 1926) and Snellgrove & Skorupski (1977, 1980) regarding the early Buddhist cultural heritage of the central region of Ladakh on the basis that the Alchi group of monuments l has to be attributed to the late 12 and early 13 th centuries AD rather than the 11 th or 12 th centuries as previously assumed (Goepper 1990). It also collects support for the new attribution published by different authors since Goepper's primary article. The nmv fairly secure attribution of the Alchi group of monuments shifts the dates by only one century} but has wide repercussions on I This term refers to the early monuments of Alchi, rvIangyu and Sumda, which are located in a narrow geographic area, have a common social, cultural and artistic background, and may be attIibuted to within a relatively narrow timeframe. -

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

Ladakhi Knowledge and Western Learning: A

LADAKHI KNOWLEDGE AND WESTERN LEARNING: A. H. FRANCKE’S TEACHERS, GUIDES AND FRIENDS IN THE WESTERN HIMALAYA1 JOHN BRAY (International Association for Ladakhi Studies) The Moravian missionary scholar August Hermann Francke (1870-1930) left a rich legacy of research on Ladakh and the neighbouring regions of the Western Himalaya. Arguably, his greatest single contribution was his Antiquities of Indian Tibet, published in two volumes by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1914 and 1926, which contains translations of the Ladakhi royal chronicle, the La dvags rgyal rabs, as well as other key historical texts. Other important contributions Fig. 1. Francke exploring the ruins of a Buddhist temple in Gompa village, near Leh, Ladakh, 1909. Photo: Pindi Lal. Courtesy of Kern Institute, University of Leiden 1 I gratefully acknowledge advice and support from a number of friends and colleagues over the years, especially Michaela Appel, Stephan Augustin, Isrun Engelhardt, Martin Klingner, Thsespal Kundan, Rüdiger Kröger, Onesimus Ngundu, Lorraine Parsons, Frank Seeliger and Hartmut Walravens. All errors remain my own responsibility. 40 JOHN BRAY include A Lower Ladakhi Version of the Kesar Saga (1905-1941) and dozens of shorter publications on topics ranging from rock inscriptions to music and folk songs.2 In February 1930 Francke died tragically young at Berlin’s Charité hospital, still aged only 59. Among the works that still lay incomplete at the time of his death was a collection of Ladakhi wedding songs that he planned to publish with the ASI. As Elena De Rossi Filibeck (2009, 2016) has explained, the ASI still hoped to bring out the text after Francke’s death. -

Études Mongoles Et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques Et Tibétaines, 51 | 2020 the Murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a Few Related Monuments

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 51 | 2020 Ladakh Through the Ages. A Volume on Art History and Archaeology, followed by Varia The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.4361 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Nils Martin, “The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 51 | 2020, Online since 09 December 2020, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/emscat.4361 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments.... 1 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines, 51 | 2020 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments...