An Archaeological Account of the Markha Valley, Ladakh. by Quentin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India, Stok Kangri Climb

INDIA, STOK KANGRI CLIMB A very achieveable 6000m trekking peak tucked into some stunning mountain terrain that is lightly trekked. Trek the wonderful Markha Valley Few people trek this route; peace and tranquility All meals in Ladakh Our small group sizes achieve greater success Access through Delhi offers huge potential for extensions to the Taj Mahal and more FAST FACTS Destination India, Ladakh Difficulty Tough Altitude 6153m Trip Duration 20 days UK ~ UK Nights on Trek 12 nights Nights in Hotels 5 nights Meals All meals in Ladakh, B&B in Delhi [email protected] +44 1529 488 159 +44 7725 943 108 page 2 INDIA STOK KANGRI CLIMB Introduction A very achieveable 6000m trekking peak tucked in amongst some of the most stunning mountain terrain in India. This a real traveller’s trip, accessing India’s least populated region (Ladakh) from Delhi (a 90 min domestic flight). Leh is one of the highest commercial airports in the world (3500m) and we take time to acclimatise here on arrival. We drive out to Chilling and camp besides the Zanskar river before beginning the trek up the Markha Valley. For many days we follow the glacial Markha river towards its source, steadily acclimatising as we go and admiring the sheer scale and variety of geology (as well as colours). The snow leopard genuinely still roams these parts and their tracks can often be seen. The iconic makeshift white parachute cafes are a welcomed sight along this route. Having acclimatised and cleared to 5100m Kongmaru La, there are still a few spectacular high passes to cross before reaching Stok Kangri’s base camp. -

Impact of Climatic Change on Agro-Ecological Zones of the Suru-Zanskar Valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India

Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Vol. 3(13), pp. 424-440, 12 November, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE ISSN 2006 - 9847©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Impact of climatic change on agro-ecological zones of the Suru-Zanskar valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India R. K. Raina and M. N. Koul* Department of Geography, University of Jammu, India. Accepted 29 September, 2011 An attempt was made to divide the Suru-Zanskar Valley of Ladakh division into agro-ecological zones in order to have an understanding of the cropping system that may be suitably adopted in such a high altitude region. For delineation of the Suru-Zanskar valley into agro-ecological zones bio-physical attributes of land such as elevation, climate, moisture adequacy index, soil texture, soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity have been taken into consideration. The agricultural productivity of the valley has been worked out according to Bhatia’s (1967) productivity method and moisture adequacy index has been estimated on the basis of Subrmmanyam’s (1963) model. The land use zone map has been superimposed on moisture adequacy index, soil texture and soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity zones to carve out different agro-ecological boundaries. The five agro-ecological zones were obtained. Key words: Agro-ecology, Suru-Zanskar, climatic water balance, moisture index. INTRODUCTION Mountain ecosystems of the world in general and India in degree of biodiversity in the mountains. particular face a grim reality of geopolitical, biophysical Inaccessibility, fragility, diversity, niche and human and socio economic marginality. -

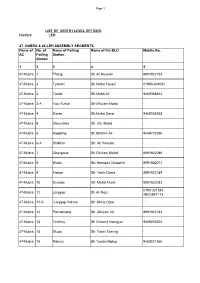

Final BLO,2012-13

Page 1 LIST OF BOOTH LEVEL OFFICER . District: LEH 47- NUBRA & 48-LEH ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS. Name of No. of Name of Polling Name of the BLO Mobile.No. AC Polling Station Station 1 3 3 4 5 47-Nubra 1 Thang Sh.Ali Hussain 8991922153 47-Nubra 2 Tyakshi Sh.Mohd Yousuf 01980-248031 47-Nubra 3 Turtuk Sh.Mohd Ali 9469368812 47-Nubra 3-A Youl Turtuk Sh:Ghulam Mohd - 47-Nubra 4 Garari Sh.Mohd Omar 9469265938 47-Nubra 5 Chulunkha Sh: Gh. Mohd - 47-Nubra 6 Bogdang Sh.Ibrahim Ali 9469732596 47-Nubra 6-A Shilkhor Sh: Ali Hassain - 47-Nubra 7 Changmar Sh.Ghulam Mehdi 8991922086 47-Nubra 8 Waris Sh: Namgail Chosphel 8991922073 47-Nubra 9 Fastan Sh: Tashi Dawa 8991922149 47-Nubra 10 Sunudo Sh: Mohd Anvar 8991922082 0190-221344 47-Nubra 11 Largyap Sh Ali Rozi /9622957173 47-Nubra 11-A Largyap Yokma Sh: Nima Otzer - 47-Nubra 12 Pachathang Sh. Ghulam Ali 8991922182 47-Nubra 13 Terchey Sh Chemet Namgyal 9469266204 47-Nubra 14 Skuru Sh; Tashi Tsering - 47-Nubra 15 Rakuru Sh Tsetan Motup 9469221366 Page 2 47-Nubra 16 Udamaru Sh:Mohd Ali 8991922151 47-Nubra 16-A Shukur Sh: Sonam Tashi - 47-Nubra 17 Hunderi Sh: Tashi Nurbu 8991922110 47-Nubra 18 Hunder Sh Ghulam Hussain 9469177470 47-Nubra 19 Hundar Dok Sh Phunchok Angchok 9469221358 47-Nubra 20 Skampuk Sh: Lobzang Thokmed - 47-Nubra 21 Partapur Smt. Sari Bano - 47-Nubra 22 Diskit Sh: Tsering Stobdan 01980-220011 47-Nubra 23 Burma Sh Tuskor Tagais 8991922100 47-Nubra 24 Charasa Sh Tsewang Stobgais 9469190201 47-Nubra 25 Kuri Sh: Padma Gurmat 9419885156 47-Nubra 26 Murgi Thukje Zangpo 9419851148 47-Nubra 27 Tongsted -

23D Markha Valley Trek

P.O Box: 26106 Kathmandu Address: Thamel, Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: +977 1 5312359 Fax: +977 1 5351070 Email: [email protected] India: 23d Markha Valley Trek Grade: Easy Altitude: 5,150 m. Tent Days: 10 Highlights: Markha Valley Trekking is one of the most varied and beautiful treks of Nepal. It ventures high into the Himalayas crossing two passes over 4575m. As it circles from the edges of the Indus Valley, down into parts of Zanskar. The trekking route passes through terrain which changes from incredibly narrow valleys to wide-open vast expanses. Markha valley trek becomes more interesting by the ancient form of Buddhism that flourishes in the many monasteries. The landscape of this trek is perched with high atop hills. The trails are decorated by elaborate “charters”(shrines) and “Mani”(prayer) walls. That further exemplifies the region’s total immersion in Buddhist culture. As we trek to the upper end of the Markha Valley, we are rewarded with spectacular views of jagged snow-capped peaks before crossing the 5150m Kongmaru La (Pass) and descending to the famous Hemis Monastery, where we end our trek. This trekking is most enjoyable for those who want to explore the ancient Buddhism with beautiful views of Himalayas. Note: B=Breakfast, L= Lunch, D=Dinner Day to day: Day 1: Arrival at Delhi o/n in Hotel : Reception at the airport, transfer and overnight at hotel. Day 2: Flight to Leh (3500m) o/n in Hotel +B: Transfer to domestic airport in the morning flight to Leh. Transfer to hotel, leisurely tour of the city to acclimatize: the old bazaar, the Palace, the Shanti Stupa, mosque; afternoon free. -

1 Jonathan Demenge

Jonathan Demenge (IDS, Brighton) In the Shadow of Zanskar: The Life of a Nepali Migrant Published in Ladakh Studies, July 2009 This article is a tribute to Thinle, a Nepali worker who died last September (2008) in Chilling. He was a driller working on the construction of the road between Nimu and Padum, along the Zanskar River. Like most other similar stories, the story of Thinle could have remained undocumented, mainly because migrants’ presence in Ladakh remains widely unstudied. The story of Thinle has a lot to tell about the living conditions of migrants who build the roads in Ladakh, their relationship to the environment – physical and imagined – and their relationship to danger. Starting from the biography of a man and his family, I attempt to understand the larger social matrix in which this history is embedded. Using the concept of structural violence (Galtung 1969; Farmer 1997; 2004) I try to shed light on the wider socio-political forces at work in this tragedy. At the same time I point to a striking reality: despite the long and important presence of working migrants in Ladakh, they remain unstudied. In spite of their substantial contribution to Ladakh’s history and development, both literally and figuratively, in the field and in the literature, migrants remain at the margin, or in the shade. The life of Thinle Sherpa I started researching road construction and road workers in Ladakh about three years ago. Thinle was one of the workers I learnt to know while I was conducting fieldwork in Chilling. Thinle and his family were very engaging people, and those who met them will surely remember them. -

Markha Valley Trek

Anchor A WALK TO REMEMBER The Markha Valley in central Ladakh is a remote high altitude desert region snugly tucked between the Ladakh and Zanskar ranges. This is one of the most diverse and picturesque treks, taking one through the Hemis National Park, remote Buddhist villages, high altitude passes and a lake—the perfect way to acquaint with the mystical kingdom of Ladakh. Words HIMMAT RANA Photography HIMMAT RANA & KAMAL RANA Snow-capped mountains in the backdrop, star-studded sky above and a river flowing right outside the camp— everything came together perfectly at this night halt site near Hanker Village 56 AUGUST 2018 DIC0818-Anchor-Markha.indd 56-57 03/08/18 3:12 pm his is a story from my bag of adventures, in order to stretch the trek to over a week, decided to tweak about two boys, or to be more precise the trekking route a little. While the conventional trekking two men, stubbornly refusing to grow up, routes start from either Chilling (three-four day trek) or trekking by themselves through the Markha Zingchen (five-six day trek) and end at Shang, ours was going Valley in Ladakh, for eight days and seven to commence from Leh city itself and boasted of an additional nights. Not sure if you choose to make a plan pass in Stok La (4,850 metres/15,910 feet), stretching the Tor the plan chooses you, but whichever way it works, it worked duration of the trek to seven to eight days. With a heavy perfectly for me and Kamal as we embarked on an impromptu Ladakhi breakfast in our bellies, we commenced our little trip to Ladakh—the land of high passes, to figure out what the adventure from Leh city. -

Figure 3. Terrace Sections

Quaternary Research (2018), 89, 281–306. Copyright © University of Washington. Published by Cambridge University Press, 2017. doi:10.1017/qua.2017.92 Quantifying episodic erosion and transient storage on the western margin of the Tibetan Plateau, upper Indus River Tara N. Jonella,b*, Lewis A. Owenc, Andrew Carterd, Jean-Luc Schwennigere, Peter D. Cliftb aSchool of Geosciences, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, Louisiana 70504, USA bDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803, USA cDepartment of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio 45221, USA dDepartment of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck College, London WC1E 7HX, United Kingdom eResearch Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3QY, United Kingdom (RECEIVED April 13, 2017; ACCEPTED September 27, 2017) Abstract Transient storage and erosion of valley fills, or sediment buffering, is a fundamental but poorly quantified process that may significantly bias fluvial sediment budgets and marine archives used for paleoclimatic and tectonic reconstructions. Prolific sediment buffering is now recognized to occur within the mountainous upper Indus River headwaters and is quantified here for the first time using optically stimulated luminescence dating, petrography, detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology, and morphometric analysis to define the timing, provenance, and volumes of prominent valley fills. This study finds that climatically modulated sediment buffering occurs over 103–104 yr time scales and results in biases in sediment compositions and volumes. Increased sediment storage coincides with strong phases of summer monsoon and winter westerlies precipitation over the late Pleistocene (32–25 ka) and mid-Holocene (~8–6 ka), followed by incision and erosion with monsoon weakening. -

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE of LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much Ofwhat Is Generally Considered to Represent the Earl

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE OF LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much ofwhat is generally considered to represent the earliest heritage of Ladakh cannot be securely dated. It even cannot be said with certainty when Buddhism reached Ladakh. Similarly, much ofwhat is recorded in inscriptions and texts concerning the period preceding the establishment of the Ladakhi kingdom in the late 151h century is either fragmentary or legendary. Thus, only a comparative study of these records together 'with the architectural and artistic heritage can provide more secure glimpses into the early history of Buddhism in Ladakh. This study outlines the most crucial historical issues and questions from the point of view of an art historian and archaeologist, drawing on a selection of exemplary monuments and o~jects, the historical value of which has in many instances yet to be exploited. vVithout aiming to be so comprehensive, the article updates the ground breaking work of A.H. Francke (particularly 1914, 1926) and Snellgrove & Skorupski (1977, 1980) regarding the early Buddhist cultural heritage of the central region of Ladakh on the basis that the Alchi group of monuments l has to be attributed to the late 12 and early 13 th centuries AD rather than the 11 th or 12 th centuries as previously assumed (Goepper 1990). It also collects support for the new attribution published by different authors since Goepper's primary article. The nmv fairly secure attribution of the Alchi group of monuments shifts the dates by only one century} but has wide repercussions on I This term refers to the early monuments of Alchi, rvIangyu and Sumda, which are located in a narrow geographic area, have a common social, cultural and artistic background, and may be attIibuted to within a relatively narrow timeframe. -

Day 1 - Arrival in Delhi

The Zanskar, The Grand Canyon of Asia, Himalayan Kayak Expedition, August 2006 Introduction High in the Zanskar mountains in the Ladakh region of Northern India lies the Zanskar river. The river itself starts at a height higher than the peak of the Matterhorn. It then winds down the breathtaking Zanskar valley, described as the Grand Canyon of Asia, for 150km until it reaches the infamous Indus river. The largest of the tributaries is the Tsarap Chu which itself flows for 150km through a series of gorges before it joins the Zanskar. Combined the Tsarap Chu and the Zanskar make one the of the greatest multiday, self supported kayaking expeditions in the world. The aim of our expedition was to undertake the self supported multi day trip down the Tsarap Chu and Zanskar. It was also our aim to spend a month exploring the rivers of Ladakh. The Team One of the most important aspects of any expedition is to have the right team. A team was put together not only due to their kayaking ability and experience, but also their social side. The group bonded well which helped when things got a little more difficult. Patrick Clissold Expedition Leader, Age 20yrs. 2nd Year MEng Mechanical Engineering. Has over 11 years kayaking experience. Grew up on the rivers of North Wales has paddled all over the UK and Europe (France, Austria, Germany, Arctic Sweden, Corsica, Pyrenees) and also a month kayaking in the Colorado. Confident on Grade IV/V. Theo Petre Age 23yrs. Ex-Imperial, Life Member, MEng Electronic & Electrical Engineering. -

Luxury - Overland to Leh - from Srinagar Package Starts From* 97,999

Luxury - Overland to Leh - From Srinagar Package starts from* 97,999 7 Nights / 8 Days - Summer Dear customer, Greetings from ThomasCook.in!! Thank you for giving us the opportunity to let us plan and arrange your forthcoming holiday. Since more than 120 years, it has been our constant endeavour to delight our clients with the packages which are designed to best suit their needs. We, at Thomascook, are constantly striving to serve the best experience from all around the world. It’s our vision to not just serve you a holiday but serve you an experience of lifetime. We hope you enjoy this holiday specially crafted for your vacation. Tour Inclusions Meals included as per itinerary Sightseeing and Transfers as per itinerary Places Covered 1 Night 2 Nights 1 Night 1 Night 2 Nights Kargil Leh Nubra Valley Pangong Leh www.thomascook.in Daywise Itinerary Srinagar - Sonamarg - Kargil (7-8 Hrs drive / 250 Kms) Pick up from Srinagar to Kargil via Sonamarg - the Meadow of Gold Depart from Srinagar as per road opening timings. The drive to Day 1 Sonamarg is another spectacular facet of country side in Kashmir in Sindh Valley. The Sindhu Valley is the largest tributary of the valley of Kashmir. Drive to Kargil the road passes through the panoramic village reach Sonamarg (2740 Mtrs). After Sonamarg mostly there is rough road and wet to Zojila pass 3527 Mtrs (Gateway of Ladakh). Continue drive towards Drass (The second coldest inhibited place in the world). Another two and half hours drive will take us to Kargil (2710 Mtrs) which has got its importance after opening the Ladakh for tourists in 1974. -

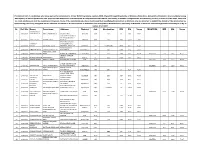

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

Études Mongoles Et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques Et Tibétaines, 51 | 2020 the Murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a Few Related Monuments

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 51 | 2020 Ladakh Through the Ages. A Volume on Art History and Archaeology, followed by Varia The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.4361 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Nils Martin, “The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 51 | 2020, Online since 09 December 2020, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/emscat.4361 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments.... 1 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines, 51 | 2020 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments...