Planning Or Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019–20 Waverley Council Annual Report

WAVERLEY COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2019–20 Waverley Council 3 CONTENTS Preface 04 Part 3: Meeting our Additional Mayor's Message 05 Statutory Requirements 96 General Manager's Message 07 Amount of rates and charges written off during the year 97 Our Response to COVID-19 and its impact on the Operational Plan and Budget 09 Mayoral and Councillor fees, expenses and facilities 97 Part 1: Waverley Council Overview 11 Councillor induction training and Our Community Vision 12 ongoing professional development 98 Our Local Government Area (LGA) Map 13 General Manager and Senior Waverley - Our Local Government Area 14 Staff Remuneration 98 The Elected Council 16 Overseas visit by Council staff 98 Advisory Committees 17 Report on Infrastructure Assets 99 Our Mayor and Councillors 18 Government Information Our Organisation 22 (Public Access) 102 Our Planning Framework 23 Public Interest Disclosures 105 External bodies exercising Compliance with the Companion Waverley Council functions 25 Animals Act and Regulation 106 Partnerships and Cooperation 26 Amount incurred in legal proceedings 107 Our Financial Snapshot 27 Progress against Equal Employment Performance Ratios 29 Opportunity (EEO) Management Plan 111 Awards received 33 Progress report - Disability Grants and Donations awarded 34 Inclusion Action Plan 2019–20 118 Grants received 38 Swimming pool inspections 127 Sponsorships received 39 Works undertaken on private land 127 Recovery and threat abatement plans 127 Part 2: Delivery Program Environmental Upgrade Agreements 127 Achievements 40 Voluntary -

Keep Australia Beautiful NSW Sustainable Cities 2020 Awards Highly Commended and Winners Table

Keep Australia Beautiful NSW Sustainable Cities 2020 Awards Highly Commended and Winners Table Waste Less Recycle More Waste Minimisation Award Sponsored by NSW EPA Highly Commended Get Rid of It Right - Recycling Improvement in Apartments Waverley Council Highly Commended RecycleSmart App and PickUp Service Sutherland Shire Council Joint Winner Smashing the Trash - Recycle, don't bin and we win! Auburn Hospital Recyclers Joint Winner The Cloth Nappy Project Sutherland Shire Council Don't Be a Tosser! Litter Action Award Sponsored by NSW EPA Highly Commended "What a load of rubbish" - Say no to single-use plastic Northern Beaches Council Highly Commended Being Litter Smart in Bondi Waverley Council Winner Seaside Scavenge Seaside Scavenge Return and Earn Litter Prevention Award Sponsored by Return and Earn Highly Commended Strathfield Car Park CDS Strathfield Municipal Council Winner Cans for Kids Auburn Hospital Recyclers School's Environmental Achievement Award Highly Commended Aquaponics for the Environment Chifley College, Bidwill Campus Highly Commended Recycling Project Northern Beaches Secondary College, Cromer Campus P&C Association Winner Seaforth for the Sea - Kitchen Garden Program Seaforth Public School Young Legend's Environment Award Highly Commended Appin Scouts Bushcare & Community Garden Group 1st Appin Scout Group Winner River Aware Parramatta River Catchment Group Recycled Organics Award Winner Closed Loop Organic Recycling Program Northern Beaches Council Heritage and Culture Award Winner 69 Redmyre Road Strathfield -

Lane Cover River Estuary – Understanding the Resource

Response to request for Quotation No: COR-RFQ-21/07 Provision of Consultancy Services to Prepare a Community Education Program: Lane Cover River Estuary – Understanding the Resource This is Our Place and a River runs through it "Just as the key to a species' survival in the natural world is its ability to adapt to local habitats, so the key to human survival will probably be the local community. If we can create vibrant, increasingly autonomous and self-reliant local groupings of people that emphasise sharing, cooperation and living lightly on the Earth, we can avoid the fate warned of by Rachel Carson and the world scientists and restore the sacred balance of life.1" 1 David Suzuki. The Sacred Balance (1997) Allen & Unwin p.8 The TITC Partnership see this quote from David Suzuki as the basis for our work on this project. 2008_02_15_Response to RFQ_Ryde_final Page 1 of 33 CONTENTS The Project Team TITC Partnership........................................................................................................... 3 Understanding of Scope of Works ................................................................................................................. 4 Program Objectives................................................................................................................................... 4 Proposed Package Elements .................................................................................................................... 4 The Catchment Community...................................................................................................................... -

Councils and Utilities

Page 1 Councils and Utilities Local Government Authorities Albury City Council: www.alburycity.nsw.gov.au Armidale Regional Council: www.armidaleregional.nsw.gov.au Ballina Shire Council: www.ballina.nsw.gov.au Balranald Shire Council: www.balranald.nsw.gov.au Bathurst Regional Council: www.bathurst.nsw.gov.au Bayside Council: www.bayside.nsw.gov.au Bega Valley Shire Council: www.begavalley.nsw.gov.au Bellingen Shire Council: www.bellingen.nsw.gov.au Berrigan Shire Council: www.berriganshire.nsw.gov.au Blacktown City Council: www.blacktown.nsw.gov.au Bland Shire Council: www.blandshire.nsw.gov.au Blayney Shire Council: www.blayney.nsw.gov.au Blue Mountains City Council: www.bmcc.nsw.gov.au Bogan Shire Council: www.bogan.nsw.gov.au Bourke, the Council of the Shire: www.bourke.nsw.gov.au Brewarrina Shire Council: www.brewarrina.nsw.gov.au Broken Hill City Council: www.brokenhill.nsw.gov.au Burwood Council: www.burwood.nsw.gov.au Law Diary Councils and Utilities Directory | 2021 Page 2 Byron Shire Council: www.byron.nsw.gov.au Cabonne Council: www.cabonne.nsw.gov.au Camden Council: www.camden.nsw.gov.au Campbelltown City Council: www.campbelltown.nsw.gov.au Canada Bay Council, City of: www.canadabay.nsw.gov.au Canterbury-Bankstown City Council: www.cbcity.nsw.gov.au Carrathool Shire Council: www.carrathool.nsw.gov.au Central Coast Council: www.centralcoast.nsw.gov.au Central Darling Shire Council: www.centraldarling.nsw.gov.au Cessnock City Council: www.cessnock.nsw.gov.au Clarence Valley Council: www.clarence.nsw.gov.au Cobar Shire Council: -

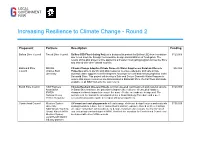

Increasing Resilience to Climate Change - Round 2

Increasing Resilience to Climate Change - Round 2 Proponent Partners Description Funding Ballina Shire Council Tweed Shire Council Ballina CBD Flood Gating Project is designed to protect the Ballina CBD from inundation $120,000 due to sea level rise through the innovative design and installation of flood gates. The results of this pilot project will be applied to a broader flood gating program across the Shire and shared with other coastal councils. Balranald Shire SEGRA Climate Change Adaptive Private Domestic Water Supplies on Rural and Remote $82,500 Council Charles Sturt Properties aims to identify and pilot measures to ensure adequate and safe private University domestic water supplies over the long term for people on rural and remote properties in the Balranald Shire. This project will develop a Safe and Secure Domestic Water Program to ensure that project resources are disseminated in Balranald Shire, the Far West and made available to all NSW non-scheme water users. Bland Shire Council NSW Farmers Climate Resilient Unsealed Roads will trial unsealed road treatment and material options $120,000 Association in Bland Shire that have the potential to improve the resilience of unsealed roads to IPWEA changes in climate impacts to ensure the most effective methods are being used. The National Heavy outcomes of the trial will be incorporated into a Road Strategy Procedure and a peer Vehicle Regulator reviewed best practice guide developed with project partners. Cumberland Council Western Sydney UV-smart and cool playgrounds will trial a range of diverse design features and materials $106,555 University in playgrounds to reduce risk of contact burns and UV exposure. -

Emergency & Pollution Incident Response

Emergency & Pollution Incident Response 10 McLachlan Ave, Artarmon April 2020 A. ASSESS (Site Supervisor/Driver) 1. Determine significance of incident? 2. Determine potential for escalation? 3. Assess risks? 4. Any impacts on people, environment, community, business stakeholders? If yes, contact the Compliance Team. 5. Is evacuation and / or Site Closure required? If yes, immediately clear the area. 6. Contact the SEQ Team 7. Do you need to notify emergency services ? If yes, contact Emergency Services. B. NOTIFY (SEQ Team) 7. Contact Emergency Services ‘000’ (if not already contacted) 8. If risk to neighbours, contact all potentially affected persons – door to door 9. Contact EPA ‘131 555’ 10a. Contact NSW Health Public Health Unit (business hours) 1300 066 055; OR 10b. Contact NSW Health (after hours – contact closest hospital on duty public health officer as below) - Camperdown (RPA) - 02 9515 6111 - Gosford - 02 4320 9730 - Liverpool (Liverpool) - 02 9828 3999 - Newcastle - 02 4924 6477 - Parramatta (Westmead) - 02 9845 5555 - Wollongong - 02 4221 6700 - Penrith - 02 4734 2000 - Hornsby – 02 9477 9400 - Randwick (Prince of Wales) - 02 9382 2222 11. Safe Work NSW 131 050 12. Local Council – See list for business and after hours contacts 13a. Fire and Rescue NSW – Emergency ‘000’ 13b. Fire and Rescue NSW – General enquiries 1300 729 579 (non emergency) C. RESPONSE PLAN (SEQ Team) 15. Contact Environmental Manager (EM) – Ros Dent 0416 685 615 16. If EM not available, contact Chief Safety, Environmental and Quality Officer – Jim Sarkis (see internal contact list) 17. Identify incident controller – this is the attending authority or if no authority the Site Supervisor / Allocator 18. -

17 October 2016 a Meeting of the WAVERLEY

Application number DA-110/2016 Site address 6-8 Bronte Road, Bondi Junction Proposal Demolition of the existing commercial building and erection of an 8 storey commercial building. Date of lodgement 24 March 2016 Owner Mac's Pty Limited Applicant Concorde Enterprises Pty Ltd Submissions Two submissions (original plans) One submission (amended plans) Cost of works $4,671, 991 (Amended Scheme) Issues Heritage, Streetscape, Right of Way Recommendation That the application be APPROVED Site Map Note: Brown colour denotes Listed Heritage Items under WLEP 2012 1. PREAMBLE 1.1 Site and Surrounding Locality A site visit was carried out on 23 May 2016. The site is identified as Lot 1 in DP 395647 known as 6-8 Bronte Road, Bondi Junction. It is located on the eastern side of Bronte Road near the intersection of Spring Street and Bronte Road. The site is predominantly rectangular in shape with a slight irregular boundary in the rear south/east corner of the site. The site has a frontage of 9.18m to Bronte Road and a depth of 27.6m and an overall area of 299m2 and is generally flat. Currently occupying the site is a single storey commercial building which is currently occupied by the NAB bank. The building covers the whole site to all boundaries and has no vehicular access. Adjoining the building to the south and east is the Westfield Commercial development and to the north is the Tea Gardens Hotel which is listed as a heritage item. Across the Road from the site there are 4 heritage listed properties known as 1,1a, 3 and 3A-5 Bronte Road. -

Waverley Council’S Esolutions Manager

feature The iconic Bondi Beach, with Sydney’s CBD on the horizon. The entirety of Bondi and its neighbouring (Amazon Web Services), a mission critical Tamarama and Bronte beaches have free Wi-Fi. cloud infrastructure that harnesses capacity at a secure data centre in Sydney. Besides physical infrastructure, the council’s GIS team has focused on creating and maintaining a highly accurate spatial mapping system with the ability to serve web-maps in relevant formats to meet specific application and user needs. “Council uses spatial information to provide tailored location specific information to the public,” said David Edwards, Waverley Council’s eSolutions Manager. This includes the launch last year of the ‘Development Enquirer’, an online interactive tool for residents to evaluate the scope of development allowed on their ANTHONY WALLACE nominated property. Waverley Council’s Discover portal provides spatial information to field staff and the community, “This is just one of the many including parking facilities as shown here. ePlanning projects the Council has implemented, utilising technology to any location. The new application has the ranks, toilets, accommodation, food shops, offer streamlined solutions for planning potential to reduce the number of enquiries shopping and places of interest. The map services,” Edwards added. to the council’s customer service centre. layers are aimed at tourists visiting the The Digital Beach Waverley Council’s Discover portal Spatial information is also being eastern beaches or Bondi Junction. (based on Pitney Bowes Spectrum Spatial utilised as part of a new website called The seaside council replacing information when users want it and Bronte and Tamarama beach as well as Analyst mapping application) provides ‘Hello Bondi’ which provides visitors and Out of the shadows an infatuation for technology in where they need it,” Betts explained. -

Planning Excellence

NSW AWARDS FOR PLANNING EXCELLENCE 2015 MESSAGE FROM THE PIA NSW PRESIDENT 4 MESSAGE FROM THE JUDGING PANEL 5 CONTENTS ABOUT PIA: LEADING EFFECTIVE PLANNING FOR PEOPLE & PLACES 6 NSW BOARD 6 2015 PIA NSW AWARD SPONSORS 7 BEST PLANNING IDEAS - LARGE PROJECT 10 BEST PLANNING IDEAS - SMALL PROJECT 12 FROM PLAN TO PLACE 14 GREAT PLACE 16 IMPROVING PLANNING PROCESSES AND PRACTICES 20 OUTSTANDING STUDENT PROJECT 22 PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNITY PLANNING 26 HARD WON VICTORY 28 YOUNG PLANNER OF THE YEAR 30 PLANNER OF THE YEAR 32 PRESIDENT’S AWARD 34 AWARD NOMINATIONS 36 2 PLANNING EXCELLENCE 2015 NSW AWARDS CONTENTS 3 MESSAGE FROM THE MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT FROM THE JUDGING PANEL Welcome to the PIA NSW contributor to the economic, However, these Awards The PIA Judges panel ideas and approaches, and and valued the opportunities Awards for Planning social and environmental should also provide evidence for 2015, made up of five some quirky considerations that planning brings to Excellence 2015. wellbeing of NSW. to the wider community and people, were proud to to show diversity in our the cities and regions. We A major initiative of the NSW Whilst this work is ongoing, I elected representatives at all receive the 27 nominations profession. Nominations were would like to congratulate Division of PIA this year is to think one only has to look at levels, as to why planning is across the 12 categories of from government, student all winning awards and undertake activities that aim the quality of this year’s PIA important and should be fully awards for 2015. -

Central West Group

S:\Data - NSW General\GROUPS\Chairs & Secretaries\GroupChairsSec July 2010.doc LGEA / IPWEA NSW REGIONAL GROUP CHAIRS AND SECRETARIES (July 2010) Central West Group Chair: Andrew Francis Parkes Shire Council Ph: 02 6861 2343 2 Cecile Street Fax: 02 6863 5931 PARKES NSW 2870 Email: [email protected] Secretary: Bill Twohill Weddin Shire Council Ph: 02 6343 1212 PO Box 125 Fax: GRENFELL NSW 2810 Email: [email protected] Hunter Valley Group Chair: Wayne Cone Ph: 02 4934 9609 Group Manager City Works & Services M: 0419 275 818 Maitland City Council Fax: Email: [email protected] Secretary: Ian Wakem Ph: 02 4934 9603 Manager Civil & Recreation Works M: 0408 218 792 Maitland City Council Fax: 02 4993 2505 Email: [email protected] Illawarra Group Chair: Lindsay Dunstan Ph: 02 4227 7200 Wollongong City Council M: 0420 934 868 Locked Bag 8821 Fax: SOUTH COAST MC NSW 252 Email: [email protected] Secretary: Josh Devitt Ph: 02 4227 7207 Wollongong City Council Locked Bag 8821 Fax: Wollongong NSW 2500 Email: [email protected] S:\Data - NSW General\GROUPS\Chairs & Secretaries\GroupChairsSec July 2010.doc 1 S:\Data - NSW General\GROUPS\Chairs & Secretaries\GroupChairsSec July 2010.doc LGEA / IPWEA NSW REGIONAL GROUP CHAIRS AND SECRETARIES (July 2010) Metropolitan North Group Chair: John Van Hesden M: 0419 239 069 North Sydney Council Ph: 02 9936 8282 PO Box 12 Fax: 02 9936 8177 NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2059 Email: [email protected] Secretary: Jim Turner Ku-Ring-Gai Council Ph: 02 -

BF Lead Agencies by Area Covered and LGA September 2017 Docx

Brighter Futures funded services: Lead agencies by areas covered and local government areas Service Provider Areas covered Local Government Areas (LGA) SDN CHILD AND FAMILY Ashfield, Botany, Burwood, Canada Bay, Canterbury, City of Sydney, Woollahra Council, City of Botany Bay, City of SERVICES INC Hurstville, Kogarah, Leichhardt, Marrickville, Randwick, Randwick, Inner West Council, Waverley Council, Rockdale, Strathfield, Sutherland, Sydney, Waverley, Burwood Council, Strathfield Council, Canada Bay Council, Woollahra Inner West Council, Canterbury-Bankstown Council, Sutherland Shire, City of Hurstville, Bayside Council, Georges River Council THE BENEVOLENT Hornsby, Hunters Hill, Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, Manly, Hornsby Shire, Hunters Hill Council, Ku-ring-gai Council, Lane SOCIETY Mosman, North Sydney, Pittwater, Ryde, Warringah, Cove Council, Northern Beaches Council, Mosman Council, Willoughby North Sydney Council, City of Ryde, City of Willoughby South West Sydney THARAWAL ABORIGINAL Campbelltown, Camden, Wingecarribee, Wollondilly City of Campbelltown, Camden Council, Wollondilly Shire, CORPORATION Wingecarribee Shire THE BENEVOLENT Bankstown, Fairfield, Liverpool City of Liverpool , City of Fairfield , Canterbury-Bankstown SOCIETY Council UNITING Campbelltown, Camden, Wingecarribee, Wollondilly City of Campbelltown, Camden Council, Wollondilly Shire, Wingecarribee Shire KARI ABORIGINAL Liverpool, Fairfield and Bankstown City of Liverpool , City of Fairfield , Canterbury-Bankstown RESOURCES INC Council METRO MIGRANT Bankstown, Fairfield -

Emergency & Pollution Incident Response

Emergency & Pollution Incident Response 20 Hearne St, Mortdale April 2020 A. ASSESS (Site Supervisor/Driver) 1. Determine significance of incident? 2. Determine potential for escalation? 3. Assess risks? 4. Any impacts on people, environment, community, business stakeholders? If yes, contact the Compliance Team. 5. Is evacuation and / or Site Closure required? If yes, immediately clear the area. 6. Contact the SEQ Team 7. Do you need to notify emergency services ? If yes, contact Emergency Services. B. NOTIFY (SEQ Team) 7. Contact Emergency Services ‘000’ (if not already contacted) 8. If risk to neighbours, contact all potentially affected persons – door to door 9. Contact EPA ‘131 555’ 10a. Contact NSW Health Public Health Unit (business hours) 1300 066 055; OR 10b. Contact NSW Health (after hours – contact closest hospital on duty public health officer as below) - Camperdown (RPA) - 02 9515 6111 - Gosford - 02 4320 9730 - Liverpool (Liverpool) - 02 9828 3999 - Newcastle - 02 4924 6477 - Parramatta (Westmead) - 02 9845 5555 - Wollongong - 02 4221 6700 - Penrith - 02 4734 2000 - Hornsby – 02 9477 9400 - Randwick (Prince of Wales) - 02 9382 2222 11. Safe Work NSW 131 050 12. Local Council – See list for business and after hours contacts 13a. Fire and Rescue NSW – Emergency ‘000’ 13b. Fire and Rescue NSW – General enquiries 1300 729 579 (non emergency) 14. Contact DPIE ‘1800 680 244’ (if there is a notifiable environmental incident) C. RESPONSE PLAN (SEQ Team) 15. Contact Environmental Manager (EM) – Ros Dent 0416 685 615 16. If EM not available, contact Chief Safety, Environmental and Quality Officer – Jim Sarkis (see internal contact list) 17.