The Luigi Cremona Archive of the Mazzini Institute of Genoa Q

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E

BOOK REVIEW Einstein’s Italian Mathematicians: Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E. Rowe Einstein’s Italian modern Italy. Nor does the author shy away from topics Mathematicians: like how Ricci developed his absolute differential calculus Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the as a generalization of E. B. Christoffel’s (1829–1900) work Birth of General Relativity on quadratic differential forms or why it served as a key By Judith R. Goodstein tool for Einstein in his efforts to generalize the special theory of relativity in order to incorporate gravitation. In This delightful little book re- like manner, she describes how Levi-Civita was able to sulted from the author’s long- give a clear geometric interpretation of curvature effects standing enchantment with Tul- in Einstein’s theory by appealing to his concept of parallel lio Levi-Civita (1873–1941), his displacement of vectors (see below). For these and other mentor Gregorio Ricci Curbastro topics, Goodstein draws on and cites a great deal of the (1853–1925), and the special AMS, 2018, 211 pp. 211 AMS, 2018, vast secondary literature produced in recent decades by the world that these and other Ital- “Einstein industry,” in particular the ongoing project that ian mathematicians occupied and helped to shape. The has produced the first 15 volumes of The Collected Papers importance of their work for Einstein’s general theory of of Albert Einstein [CPAE 1–15, 1987–2018]. relativity is one of the more celebrated topics in the history Her account proceeds in three parts spread out over of modern mathematical physics; this is told, for example, twelve chapters, the first seven of which cover episodes in [Pais 1982], the standard biography of Einstein. -

History History

HISTORY HISTORY 1570 The first traces of the entrepreneurial activity of the Sella family go back to the second half of the sixteenth century, when Bartolomeo Sella and his son Comino worked as entrepreneurs in the textile field, having fabrics produced by wool artisans and financing the entrepreneurs of the Biellese community. The family has its origin in the Valle di Mosso, where its activities concentrated for a long time in the textile and agricultural fields. In the nineteenth century, the Sella family was among the leading figures 1817 of the first steps of industrialization in the textile field.In 1815, Pietro Sella, following a trip to England where he went as a worker to understand how processing machines operated, bought from the inventor and entrepre- neur William Cockerill, who had opened a textile machinery manufacturing workshop in Belgium, eight different examples of spinning machines (for beating, peeling, removing, carding, spinning in bulk and finally, to gar- nish and trim clothes). For each imported unit, Pietro Sella reproduced two others. In 1817, the King of Sardinia authorized him to start produc- tion. The machines soon began to make a decisive contribution to the growth of the turnover of the family company. A few years later, his brother Giovanni Battista also introduced the same machines. Pietro Sella (1784 - 1827) 1827 Maurizio and Rosa had twenty children, four of whom car- ried on the business: Francesco, Gaudenzio, Giuseppe Venanzio and Quinti- no. Quintino Sella, born in 1827, became Minister of Finance of the newborn Kingdom of Italy for the first time in 1862, dedicating himself to the consoli- dation of the budget. -

The Birth of Hyperbolic Geometry Carl Friederich Gauss

The Birth of Hyperbolic Geometry Carl Friederich Gauss • There is some evidence to suggest that Gauss began studying the problem of the fifth postulate as early as 1789, when he was 12. We know in letters that he had done substantial work of the course of many years: Carl Friederich Gauss • “On the supposition that Euclidean geometry is not valid, it is easy to show that similar figures do not exist; in that case, the angles of an equilateral triangle vary with the side in which I see no absurdity at all. The angle is a function of the side and the sides are functions of the angle, a function which, of course, at the same time involves a constant length. It seems somewhat of a paradox to say that a constant length could be given a priori as it were, but in this again I see nothing inconsistent. Indeed it would be desirable that Euclidean geometry were not valid, for then we should possess a general a priori standard of measure.“ – Letter to Gerling, 1816 Carl Friederich Gauss • "I am convinced more and more that the necessary truth of our geometry cannot be demonstrated, at least not by the human intellect to the human understanding. Perhaps in another world, we may gain other insights into the nature of space which at present are unattainable to us. Until then we must consider geometry as of equal rank not with arithmetic, which is purely a priori, but with mechanics.“ –Letter to Olbers, 1817 Carl Friederich Gauss • " There is no doubt that it can be rigorously established that the sum of the angles of a rectilinear triangle cannot exceed 180°. -

The True Story Behind Frattini's Argument *

Advances in Group Theory and Applications c 2017 AGTA - www.advgrouptheory.com/journal 3 (2017), pp. 117–129 ISSN: 2499-1287 DOI: 10.4399/97888255036928 The True Story Behind Frattini’s Argument * M. Brescia — F. de Giovanni — M. Trombetti (Received Apr. 12, 2017 — Communicated by Dikran Dikranjan) Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 01A55, 20D25 Keywords: Frattini’s Argument; Alfredo Capelli In his memoir [7] Intorno alla generazione dei gruppi di operazioni (1885), Giovanni Frattini (1852–1925) introduced the idea of what is now known as a non-generating element of a (finite) group. He proved that the set of all non- generating elements of a group G constitutes a normal subgroup of G, which he named Φ. This subgroup is today called the Frattini sub- group of G. The earliest occurrence of this de- nomination in literature traces back to a pa- per of Reinhold Baer [1] submitted on Sep- tember 5th, 1952. Frattini went on proving that Φ is nilpotent by making use of an in- sightful, renowned argument, the intellectual ownership of which is the subject of this note. We are talking about what is nowadays known as Frattini’s Argument. Giovanni Frattini was born in Rome on January 8th, 1852 to Gabrie- le and Maddalena Cenciarelli. In 1869, he enrolled for Mathematics at the University of Rome, where he graduated in 1875 under the * The authors are members of GNSAGA (INdAM), and work within the ADV-AGTA project 118 M. Brescia – F. de Giovanni – M. Trombetti supervision of Giuseppe Battaglini (1826–1894), together with other up-and-coming mathematicians such as Alfredo Capelli. -

Algebraic Research Schools in Italy at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: the Cases of Rome, Palermo, and Pisa

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematica 31 (2004) 296–309 www.elsevier.com/locate/hm Algebraic research schools in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century: the cases of Rome, Palermo, and Pisa Laura Martini Department of Mathematics, University of Virginia, PO Box 400137, Charlottesville, VA 22904-4137, USA Available online 28 January 2004 Abstract The second half of the 19th century witnessed a sudden and sustained revival of Italian mathematical research, especially in the period following the political unification of the country. Up to the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th, Italian professors—in a variety of institutional settings and with a variety of research interests— trained a number of young scholars in algebraic areas, in particular. Giuseppe Battaglini (1826–1892), Francesco Gerbaldi (1858–1934), and Luigi Bianchi (1856–1928) defined three key venues for the promotion of algebraic research in Rome, Palermo, and Pisa, respectively. This paper will consider the notion of “research school” as an analytic tool and will explore the extent to which loci of algebraic studies in Italy from the second half of the 19th century through the opening decades of the 20th century can be considered as mathematical research schools. 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Sommario Nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento, specialmente dopo l’unificazione del paese, la ricerca matematica in Italia conobbe una vigorosa rinascita. Durante gli ultimi decenni del diciannovesimo secolo e i primi del ventesimo, matematici italiani appartenenti a diverse istituzioni e con interessi in diversi campi di ricerca, formarono giovani studiosi in vari settori dell’algebra. -

Della Matematica in Italia

Intreccio Risorgimento, Unità d'Italia e geometria euclidea... il “Risorgimento” della matematica in Italia La ripresa della matematica italiana nell’Ottocento viene solitamente fatta coincidere con la data emblematica del !"#, cioè con l’unifica%ione del paese . In realtà altre date, precedenti a &uesta, sono altrettanto significative di 'aolo (uidera La ripresa della matematica italiana nell’Ottocento viene solitamente fatta coincidere con la data emblematica del 1860, cioè con l’unificazione del paese . In realtà altre date, precedenti a uesta, sono altrettanto si!nificative . "el 1839 si tenne a %isa il primo &on!resso de!li scienziati italiani, esperienza, uesta dei con!ressi, c'e prose!u( fino al 1847. + uesti appuntamenti parteciparono non solo i matematici della penisola, ma anche uelli stranieri . Il &on!resso del 1839 rappresent, un enorme passo avanti rispetto alla situazione di isolamento de!li anni precedenti. -n anno di svolta fu pure il 1850 uando si diede avvio alla pubblicazione del primo periodico di matematica Annali di scienze fisiche e matematiche / mal!rado il titolo !li articoli ri!uardavano uasi totalmente la matematica. La rivista , dal 1857, prese il nome di Annali di matematica pura ed applicata. I!nazio &ant0, fratello del pi0 celebre &esare, pubblic, nel 1844 il volume L’Italia scientifica contemporanea nel uale racco!lieva le notizie bio!rafiche e scientifiche de!li italiani attivi in campo culturale e uindi anche nella matematica. "ella prima metà dell’Ottocento la matematica in realtà era in!lese, francese o tedesca . L( erano i !randi nomi. 1a uei con!ressi e da!li +tti relativi pubblicati successivamente si evinceva c'e il settore andava risve!liandosi. -

Riemann's Contribution to Differential Geometry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematics 9 (1982) l-18 RIEMANN'S CONTRIBUTION TO DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY BY ESTHER PORTNOY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, URBANA, IL 61801 SUMMARIES In order to make a reasonable assessment of the significance of Riemann's role in the history of dif- ferential geometry, not unduly influenced by his rep- utation as a great mathematician, we must examine the contents of his geometric writings and consider the response of other mathematicians in the years immedi- ately following their publication. Pour juger adkquatement le role de Riemann dans le developpement de la geometric differentielle sans etre influence outre mesure par sa reputation de trks grand mathematicien, nous devons &udier le contenu de ses travaux en geometric et prendre en consideration les reactions des autres mathematiciens au tours de trois an&es qui suivirent leur publication. Urn Riemann's Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der Differentialgeometrie richtig einzuschZtzen, ohne sich von seinem Ruf als bedeutender Mathematiker iiberm;issig beeindrucken zu lassen, ist es notwendig den Inhalt seiner geometrischen Schriften und die Haltung zeitgen&sischer Mathematiker unmittelbar nach ihrer Verijffentlichung zu untersuchen. On June 10, 1854, Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann read his probationary lecture, "iber die Hypothesen welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen," before the Philosophical Faculty at Gdttingen ill. His biographer, Dedekind [1892, 5491, reported that Riemann had worked hard to make the lecture understandable to nonmathematicians in the audience, and that the result was a masterpiece of presentation, in which the ideas were set forth clearly without the aid of analytic techniques. -

"Matematica E Internazionalità Nel Carteggio Fra Guccia E Cremona E I Rendiconti Del Circolo Matematico "

"Matematica e internazionalità nel carteggio fra Guccia e Cremona e i Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico " Cinzia Cerroni Università di Palermo Giovan Battista Guccia (Palermo 1855 – 1914) Biography of Giovan Battista Guccia He graduated in Rome in 1880, where he had been a student of Luigi Cremona, but already before graduation he attended the life mathematics and published a work of geometry. In 1889 was appointed professor of higher geometry at the University of Palermo and in 1894 was appointed Ordinary. In 1884 he founded, with a personal contribution of resources and employment, the Circolo Matematico di Palermo, whose ”Rendiconti" became, a few decades later, one of the most important international mathematical journals. He it was, until his death, the director and animator. At the untimely end, in 1914, he left fifty geometric works, in the address closely cremoniano. Luigi Cremona (Pavia 1830- Roma 1903) Biography of Luigi Cremona He participated as a volunteer in the war of 1848. He entered the University of Pavia in 1849. There he was taught by Bordoni, Casorati and Brioschi. On 9 May 1853 he graduated in civil engineering at the University of Pavia. He taught for several years in Middle Schools of Pavia, Cremona and Milan. In 1860 he became professor of Higher Geometry at the University of Bologna. In October 1867, on Brioschi's recommendation, was called to Polytechnic Institute of Milan, to teach graphical statics. He received the title of Professor in 1872 while at Milan. He moved to Rome on 9 October 1873, as director of the newly established Polytechnic School of Engineering. -

HOMOTECIA Nº 11-15 Noviembre 2017

HOMOTECIA Nº 11 – Año 15 Miércoles, 1º de Noviembre de 2017 1 En una editorial anterior, comentamos sobre el consejo que le dio una profesora con años en el ejercicio del magisterio a un docente que se iniciaba en la docencia, siendo que ambos debían enseñar matemática: - Si quieres obtener buenos resultados en el aprendizaje de los alumnos que vas a atender, para que este aprendizaje trascienda debes cuidar el lenguaje, el hablado y el escrito, la ortografía, la redacción, la pertinencia. Desde la condición humana, promover la cordialidad y el respeto mutuo, el uso de la terminología correcta de nuestro idioma, que posibilite la claridad de lo que se quiere exponer, lo que se quiere explicar, lo que se quiere evaluar. Desde lo específico de la asignatura, ser lexicalmente correcto. El hecho de ser docente de matemática no significa que eso te da una licencia para atropellar el lenguaje. En consecuencia, cuando utilices los conceptos matemáticos y trabajes la operatividad correspondiente, utiliza los términos, definiciones, signos y símbolos que esta disciplina ha dispuesto para ellos. Debes esforzarte en hacerlo así, no importa que los alumnos te manifiesten que no entienden. Tu preocupación es que aprendan de manera correcta lo que se les enseña. Es una prevención para evitarles dificultades en el futuro . Traemos a colación lo de este consejo porque consideramos que es un tema que debe tratarse con mucha amplitud. El problema de hablar y escribir bien no es solamente característicos en los alumnos sino que también hay docentes que los presentan. Un alumno, por más que asista continuamente a la escuela, es afectado por el entorno cultural familiar en el que se desenvuelve. -

Bianchi, Luigi.Pdf 141KB

Centro Archivistico BIANCHI, LUIGI Elenco sommario del fondo 1 Indice generale Introduzione.....................................................................................................................................................2 Carteggio (1880-1923)......................................................................................................................................2 Carteggio Saverio Bianchi (1936 – 1954; 1975)................................................................................................4 Manoscritti didattico scientifici........................................................................................................................5 Fascicoli............................................................................................................................................................6 Introduzione Il fondo è pervenuto alla Biblioteca della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa per donazione degli eredi nel 1994-1995; si tratta probabilmente solo di una parte della documentazione raccolta da Bianchi negli anni di ricerca e insegnamento. Il fondo era corredato di un elenco dattiloscritto a cura di Paola Piazza, in cui venivano indicati sommariamente i contenuti delle cartelle. Il materiale è stato ordinato e descritto da Sara Moscardini e Manuel Rossi nel giugno 2014. Carteggio (1880-1923) La corrispondenza presenta oltre 100 lettere indirizzate a L. B. dal 1880 al 1923, da illustri studiosi del XIX-XX secolo come Eugenio Beltrami, Enrico Betti, A. von Brill, Francesco Brioschi, -

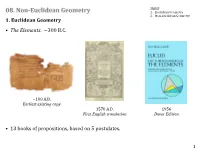

08. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1

Topics: 08. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1. Euclidean Geometry 2. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1. Euclidean Geometry • The Elements. ~300 B.C. ~100 A.D. Earliest existing copy 1570 A.D. 1956 First English translation Dover Edition • 13 books of propositions, based on 5 postulates. 1 Euclid's 5 Postulates 1. A straight line can be drawn from any point to any point. • • A B 2. A finite straight line can be produced continuously in a straight line. • • A B 3. A circle may be described with any center and distance. • 4. All right angles are equal to one another. 2 5. If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side together less than two right angles, then the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles are together less than two right angles. � � • � + � < 180∘ • Euclid's Accomplishment: showed that all geometric claims then known follow from these 5 postulates. • Is 5th Postulate necessary? (1st cent.-19th cent.) • Basic strategy: Attempt to show that replacing 5th Postulate with alternative leads to contradiction. 3 • Equivalent to 5th Postulate (Playfair 1795): 5'. Through a given point, exactly one line can be drawn parallel to a given John Playfair (1748-1819) line (that does not contain the point). • Parallel straight lines are straight lines which, being in the same plane and being • Only two logically possible alternatives: produced indefinitely in either direction, do not meet one 5none. Through a given point, no lines can another in either direction. (The Elements: Book I, Def. -

On the Role Played by the Work of Ulisse Dini on Implicit Function

On the role played by the work of Ulisse Dini on implicit function theory in the modern differential geometry foundations: the case of the structure of a differentiable manifold, 1 Giuseppe Iurato Department of Physics, University of Palermo, IT Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Palermo, IT 1. Introduction The structure of a differentiable manifold defines one of the most important mathematical object or entity both in pure and applied mathematics1. From a traditional historiographical viewpoint, it is well-known2 as a possible source of the modern concept of an affine differentiable manifold should be searched in the Weyl’s work3 on Riemannian surfaces, where he gave a new axiomatic description, in terms of neighborhoods4, of a Riemann surface, that is to say, in a modern terminology, of a real two-dimensional analytic differentiable manifold. Moreover, the well-known geometrical works of Gauss and Riemann5 are considered as prolegomena, respectively, to the topological and metric aspects of the structure of a differentiable manifold. All of these common claims are well-established in the History of Mathematics, as witnessed by the work of Erhard Scholz6. As it has been pointed out by the Author in [Sc, Section 2.1], there is an initial historical- epistemological problem of how to characterize a manifold, talking about a ‘’dissemination of manifold idea’’, and starting, amongst other, from the consideration of the most meaningful examples that could be taken as models of a manifold, precisely as submanifolds of a some environment space n, like some projective spaces ( m) or the zero sets of equations or inequalities under suitable non-singularity conditions, in this last case mentioning above all of the work of Enrico Betti on Combinatorial Topology [Be] (see also Section 5) but also that of R.