Clicking Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Please Download Issue 2 2012 Here

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. June 2012. Vol. V:2. 1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Academic life in newly Södertörn University, Stockholm founded Baltic States BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com LANGUAGE &GYÖR LITERATUREGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG GYÖRGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG also in this issue ILL. LARS RODVALDR SIBERIA-EXILES / SOUNDPOETRY / SREBRENICA / HISTORY-WRITING IN BULGARIA / HOMOSEXUAL RIGHTS / RUSSIAN ORPHANAGES articles2 editors’ column Person, myth, and memory. Turbulence The making of Raoul Wallenberg and normality IN auGusT, the 100-year anniversary of seek to explain what it The European spring of Raoul Wallenberg’s birth will be celebrated. is that makes someone 2012 has been turbulent The man with the mission of protect- ready to face extraordinary and far from “normal”, at ing the persecuted Jewish population in challenges; the culture- least when it comes to Hungary in final phases of World War II has theoretical analyzes of certain Western Euro- become one of the most famous Swedes myth, monuments, and pean exemplary states, of the 20th century. There seem to have heroes – here, the use of affected as they are by debt been two decisive factors in Wallenberg’s history and the need for crises, currency concerns, astonishing fame, and both came into play moral exemplars become extraordinary political around the same time, towards the end of themselves the core of the solutions, and growing the 1970s. The Holocaust had suddenly analysis. public support for extremist become the focus of interest for the mass Finally: the historical political parties. -

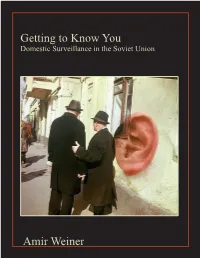

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime -

The Folklore of Deported Lithuanians Essay by Vsevolod Bashkuev

dislocating literature 15 Illustration: Moa Thelander Moa Illustration: Songs from Siberia The folklore of deported Lithuanians essay by Vsevolod Bashkuev he deportation of populations in the Soviet Union oblast, and the Buryat-Mongolian Autonomous Soviet Social- accommodation-sharing program. Whatever the housing ar- during Stalin’s rule was a devious form of political ist Republic. A year later, in March, April, and May 1949, in rangements, the exiles were in permanent contact with the reprisal, combining retribution (punishment for the wake of Operation Priboi, another 9,633 families, 32,735 local population, working side by side with them at the facto- being disloyal to the regime), elements of social people, were deported from their homeland to remote parts ries and collective farms and engaging in barter; the children engineering (estrangement from the native cultural environ- of the Soviet Union.2 of both exiled and local residents went to the same schools ment and indoctrination in Soviet ideology), and geopolitical The deported Lithuanians were settled in remote regions and attended the same clubs and cultural events. Sometimes imperatives (relocation of disloyal populations away from of the USSR that were suffering from serious labor shortages. mixed marriages were contracted between the exiles and the vulnerable borders). The deportation operations were ac- Typically, applications to hire “new human resources” for local population. companied by the “special settlement” of sparsely populated their production facilities were -

Leps A. Soviet Power Still Thrives in Estonia

Leps A. ♦ The Soviet power still thrives in Estonia Abstract: It is a historical fact that world powers rule on the fate of small countries. Under process of privatization in the wake of the newly regained independence of Estonia in 1991, a new Estonian elite emerged, who used to be managers of ministries, industries, collective farms and soviet farms. They were in a position to privatize the industrial and agricultural enterprises and they quite naturally became the crème de la crème of the Estonian people, having a lot of power and influence because they had money, knowledge, or special skills. They became capitalists, while the status of the Soviet-time salaried workers remained vastly unchanged: now they just had to report to the nouveaux riches, who instituted the principles of pre-voting (a run-up to the election proper) and electronic voting, to be able to consolidate their gains. However those principles are concepts, unknown to the basic law (Constitution) of the Republic of Estonia – hence the last elections of the 13th composition of the Parliament held in 2015 are null and void ab initio. Keywords: elite of the Republic of Estonia; deportation; „every kitchen maid can govern the state“; industry; agriculture; banking; privatisation; basic law of the Republic of Estonia (Constitution); pre-voting; electronic voting. How they did the Republic of Estonia in It is a very sad story in a nutshell, evolving from 1939, when events and changes started to happen in Europe, having important effects on Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania that couldn’t be stopped. Two major European powers - Germany and the Soviet Union reared their ugly heads and, as had invariably happened in the past, took to deciding on destiny of the small states. -

The Deportation Operation “Priboi” in 1949

The deporTaTion operaTion “priboi” in 1949 Aigi RAhi-TAmm, AndRes KAhAR The operation known as the 1949 deportations materials from6 Russian archives have been of con- was the most massive violent undertaking carried siderable use. out by the Soviet authorities simultaneously in all three Baltic states. The planning of deporTaTions Deportations have been fairly1 thoroughly dealt with in Estonian historiography. It is not unequivocally clear even today when or 2 by whom the idea of a large deportations operation Lists of the deportees have been published; the in the Baltic states was first mentioned. The neces- timeline of events has been documented, as well sity of deportations had been mentioned both in as the individuals and institutions associated with the context of the sovietisation of agriculture and carrying them out; and3 several autobiographies suppression of the Forest Brothers movement. In have been published. The present study is mostly early 1948, Andrei Zhdanov, Secretary of the Central based on archive records available4 in Estonia and Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet papers published in Estonia. Also the works5 of Union (hereinafter the CPSU CC) received a report Russian, Latvian and Moldovan historians and from the officials who had inspected the situation 1 Aigi Rahi-Tamm, “Nõukogude repressioonide uurimisest Eestis” (On the Study of Soviet Repressions in Estonia) in Eesti NSV aastatel 1940–1953 : Sovetiseerimise mehhanismid ja tagajärjed Nõukogude Liidu ja Ida–Euroopa arengute kontekstis (Estonian SSR in 1940–1953 : the Mechanisms and Consequences of Sovietisation in the Context of Developments in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe), compiled by T. -

I ESCALATION in the BALTICS: an OVERVIEW of RUSSIAN INTENT Author-Joseph M. Hays Jr. United States Air Force Submitted in Fulfil

ESCALATION IN THE BALTICS: AN OVERVIEW OF RUSSIAN INTENT Author-Joseph M. Hays Jr. United States Air Force Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for AIR UNIVERSITY ADVANCED RESEARCH (NEXT GENERATION INTELLIGENCE, SURVEILLANCE, AND RECONNAISSANCE) in part of SQUADRON OFFICER SCHOOL VIRTUAL – IN RESIDENCE AIR UNIVERSITY MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE December 2020 Advisor: Ronald Prince ISR 200 Course Director Curtis E. LeMay Center i THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ii ABSTRACT Russia poses a significant threat to the Baltics. Through hybrid warfare means, Russia has set the stage for invasion and occupation in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. This paper begins with an exploration of the motivations and history Russia has for occupying the Baltics by primarily addressing the issues of energy dominance and the Baltics’ precedence for insurgency. The Baltic states have whole-of-nation defense strategies in conjunction with NATO interoperability which should most likely deter a full-scale invasion on the part of Russia, despite Russia possessing military superiority. However, Russia has a history of sewing dissent through information operations. This paper addresses how Russia could theoretically occupy an ethnically Russian city of a Baltic country and explores what measures Russia may take to hold onto that territory. Specifically as it pertains to a nuclear response, Russia may invoke an “escalate to de-escalate” strategy, threatening nuclear war with intermediate-range warheads. This escalation would take place through lose interpretation of Russian doctrine and policy that is supposedly designed to protect the very existence of the Russian state. This paper concludes by discussing ways forward with research, specifically addressing NATO’s full spectrum of response to Russia’s escalation through hybrid warfare. -

Acta Historica Neosoliensia

ACTA HISTORICA NEOSOLIENSIA VEDECKÝ ČASOPIS PRE HISTORICKÉ VEDY 23 / 2020 Vol. 1 BELIANUM ACTA HISTORICA NEOSOLIENSIA Vedecký časopis pre historické vedy Vychádza 2x ročne Vydáva: Belianum. Vydavateľstvo Univerzity Mateja Bela v Banskej Bystrici EV 5543/17 Sídlo vydavateľa: Národná 12, 974 01 Banská Bystrica IČO vydavateľa: IČO 30 232 295 Dátum vydania: jún 2020 © Belianum. Vydavateľstvo Univerzity Mateja Bela v Banskej Bystrici ISSN 1336-9148 (tlačená verzia) ISSN 2453-7845 (elektronická verzia) Časopis je registrovaný v medzinárodných databázach: European Reference Index for the Humanities (ERIH PLUS) Central and Eastern European Online Library (CEEOL) Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (CEJSH) Redakcia: Pavol Maliniak (šéfredaktor) Michal Šmigeľ (výkonný redaktor) Patrik Kunec Imrich Nagy Oto Tomeček Redakčná rada: Rastislav Kožiak (predseda) Barnabás Guitman (Piliscsaba, Maďarsko) Éva Gyulai (Miskolc, Maďarsko) Bohdan Halczak (Zielona Góra, Poľsko) Jiří Knapík (Opava, Česká republika) Vjačeslav Meňkovskij (Minsk, Bielorusko) Maxim Mordovin (Budapešť, Maďarsko) Vincent Múcska (Bratislava, Slovensko) Martin Pekár (Košice, Slovensko) Petr Popelka (Ostrava, Česká republika) Jan Randák (Praha, Česká republika) Jerzy Sperka (Katowice, Poľsko) Ján Steinhübel (Bratislava, Slovensko) OBSAH Články GLOCKO, F.: Banskobystrický štvorlístok zlatníkov 19. storočia. Život a dielo Juraja Sodomku, Karola Miškovského, Alojza Herritza a Františka Franciscyho ........................................................................... -

The Baltic States and Russia Autor(Es)

(Re)securitisation in Europe: the Baltic States and Russia Autor(es): Fernandes, Sandra; Correia, Daniel Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/43549 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-6336_18_7 Accessed : 15-Oct-2020 23:16:18 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt DEBATER A EUROPA 18 jan-jun 2018 RELAÇÕES EXTERNAS DA UNIÃO EUROPEIA A LESTE EXTERNAL RELATIONS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION TOWARDS THE EAST DEBATER A EUROPA Periódico do CIEDA e do CEIS20 , em parceria com GPE e a RCE. -

Daniel Baldwin Hess Tiit Tammaru Editors Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries the Legacy of Central Planning in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania the Urban Book Series

The Urban Book Series Daniel Baldwin Hess Tiit Tammaru Editors Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries The Legacy of Central Planning in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania The Urban Book Series Editorial Board Fatemeh Farnaz Arefian, Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London, London, UK Michael Batty, Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, University College London, London, UK Simin Davoudi, Planning & Landscape Department GURU, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK Geoffrey DeVerteuil, School of Planning and Geography, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK Andrew Kirby, New College, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA Karl Kropf, Department of Planning, Headington Campus, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK Karen Lucas, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK Marco Maretto, DICATeA, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Parma, Parma, Italy Fabian Neuhaus, Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada Vitor Manuel Aráujo de Oliveira, Porto University, Porto, Portugal Christopher Silver, College of Design, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA Giuseppe Strappa, Facoltà di Architettura, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Roma, Italy Igor Vojnovic, Department of Geography, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA Jeremy W. R. Whitehand, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK The Urban Book Series is a resource for urban studies and geography research worldwide. It provides a unique and innovative resource for the latest developments in the field, nurturing a comprehensive and encompassing publication venue for urban studies, urban geography, planning and regional development. The series publishes peer-reviewed volumes related to urbanization, sustain- ability, urban environments, sustainable urbanism, governance, globalization, urban and sustainable development, spatial and area studies, urban management, transport systems, urban infrastructure, urban dynamics, green cities and urban landscapes. -

Fourth Section Decision the Facts

FOURTH SECTION DECISION Applications nos. 45520/04 and 19363/05 Nikolajs LARIONOVS against Latvia and Nikolay TESS against Latvia The European Court of Human Rights (Fourth Section), sitting on 25 November 2014 as a Chamber composed of: Päivi Hirvelä, President, Ineta Ziemele, George Nicolaou, Ledi Bianku, Nona Tsotsoria, Zdravka Kalaydjieva, Paul Mahoney, judges, and Françoise Elens-Passos, Section Registrar, Having regard to the above applications lodged on 27 September 2004 and 29 March 2005 respectively, Having regard to the partial decisions of 4 January 2008, Having regard to the observations submitted by the respondent Government and the observations in reply submitted by the applicants, Having deliberated, decides as follows: THE FACTS 1. The applicant in the first application, Mr Nikolajs Larionovs (“first applicant”), was a Latvian national, who was born in 1921. He died in 2005 after lodging his application. On 11 January 2006 his son, Mr Sergejs Larionovs, informed the Court that he wished to pursue the application on behalf of his father. 2. The applicant in the second application, Mr Nikolay Tess (“second applicant”), was a Russian national. He was born in 1921 and died in 2006. His widow, Mrs Tamara Karlovna Ziyberg, informed the Court that she wished to pursue the application. Following her death in 2011, the second 2 LARIONOVS v. LATVIA AND TESS v. LATVIA DECISION applicant’s brother informed the Court of his wish to pursue the application on behalf of Mr Tess. 3. The applicants were represented before the Court by Mr M. Ioffe, a lawyer practising in Riga. 4. The Latvian Government (“the respondent Government”) were represented by their Agents, Mrs I. -

Folha De Rosto EEG.Cdr

Universidade do Minho Escola de Economia e Gestão Daniel Ferreira Correia The Baltic states' securitisation discourses and practices in the face of Russia's assertiveness The Baltic states' securitisation discourses and practices in the assertiveness face of Russia's Daniel Ferreira Correia Daniel Ferreira Minho | 2017 U outubro de 2017 Universidade do Minho Escola de Economia e Gestão Daniel Ferreira Correia The Baltic states' securitisation discourses and practices in the face of Russia's assertiveness Tese de Mestrado Mestrado em Relações Internacionais Trabalho efetuado sob a orientação da Professora Doutora Sandra Dias Fernandes outubro de 2017 DECLARAÇÃO Nome: Daniel Ferreira Correia Endereço electrónico: [email protected] Título dissertação: The Baltic states’ securitisation discourses and practices in the face of Russia’s assertiveness Orientadora: Professora Doutora Sandra Dias Fernandes Ano de conclusão: 2017 Designação do Mestrado: Mestrado em Relações Internacionais É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTA TESE/TRABALHO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE; Universidade do Minho, ___/___/______ Assinatura: ________________________________________________ ii Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Sandra Dias Fernandes, for the patient guidance and advice she has provided me. I have been very lucky to have a supervisor who cared so much about my work and who took the time to give me detailed suggestions on how to improve my dissertation. I must also express my gratitude to my mother and my brother José, for encouraging me in all of my pursuits and standing by my side unconditionally. iii iv Abstract Owing to the Russian Federation’s growing assertiveness in the international arena, amply demonstrated by the annexation of Crimea in March 2014, the three Baltic states – Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia – have been presented as potential targets of the Kremlin’s revisionism. -

Communism: Its Ideology, Its History, and Its Legacy COMMUNISM: ITS IDEOLOGY, ITS HISTORY

COMMUNISM: ITS IDEOLOGY, ITS HISTORY, and ITS LEGACY Third Edition Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation© 1 2 Communism: Its Ideology, Its History, and Its Legacy COMMUNISM: ITS IDEOLOGY, ITS HISTORY, and ITS LEGACY Paul Kengor, Ph.D. Professor of Political Science Grove City College Lee Edwards, Ph.D. Chairman Emeritus Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation Claire McCaffery Griffin, MA Claire Griffin Consulting, LLC PUBLISHED BY Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation 300 New Jersey Avenue NW, Suite 900, Washington, DC 20001 www.victimsofcommunism.org Third Edition Copyright ©2021 Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation 300 New Jersey Avenue NW, Suite 900 Washington, DC 20001 [email protected] Printed in the United States 4 Communism: Its Ideology, Its History, and Its Legacy Table of Contents Introduction .........................................................................7 Karl Marx and His Legacy .............................................................9 Lenin and the Bolshevik Revolution .................................................. 27 Stalin and the Soviet Union ......................................................... 39 Independence, Occupation, and Deportation in the Baltics ..............................51 Mao and China .....................................................................81 Kim Il-Sung and North Korea ........................................................ 93 Pol Pot and Cambodia .............................................................103