The Hayes History Journal 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

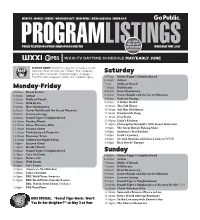

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

NPR Mideast Coverage April - June 2012

NPR Mideast Coverage April - June 2012 This report covers NPR's reporting on events and trends related to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians during the second quarter of 2012. The report begins with an assessment of the 37 stories and interviews, covered by this review, that aired from April through June on radio shows produced by NPR. The 37 radio items is just one more than the lowest number for any quarter (in July-September 2008) during the past ten years. Over that period, NPR programs have carried an average of nearly 100 items per quarter related to Israel, the Palestinians, or both. I also reviewed 20 news stories, blogs and other items carried exclusively on NPR's website. All of the radio and website-only items covered by this review are shown on the "Israel-Palestinian coverage" page of the website. The opinions expressed in this report are mine alone. Accuracy I carefully reviewed all items for factual accuracy, with special attention to the radio stories, interviews and website postings produced by NPR staffers. NPR's coverage of the region continues to be remarkably accurate for a news organization with very tight deadlines. NPR has posted no corrections on its website for stories that originated during the April-June quarter; two corrections were posted in April concerning items dealt with in my report for the January-March quarter. I found no outright inaccuracies during the period, but I will point out two instances of misleading use of language. Freelance correspondent Sheera Frenkel reported for All Things Considered on May 8 about the status of a hunger strike among Palestinian prisoners. -

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

Patterns in the Mindset Behind Organized Mass Killing

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 8 6-2018 Democidal Thinking: Patterns in the Mindset Behind Organized Mass Killing Gerard Saucier University of Oregon Laura Akers Oregon Research Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Saucier, Gerard and Akers, Laura (2018) "Democidal Thinking: Patterns in the Mindset Behind Organized Mass Killing," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 12: Iss. 1: 80-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.12.1.1546 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Democidal Thinking: Patterns in the Mindset Behind Organized Mass Killing Acknowledgements Thanks are due to Seraphine Shen-Miller, Ashleigh Landau, and Nina Greene for assistance with various aspects of this research. This article is available in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss1/8 Democidal Thinking: Patterns in the Mindset Behind Organized Mass Killing Gerard Saucier University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon, USA Laura Akers Oregon Research Institute Eugene, Oregon, USA In such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners. –Howard Zinn1 Introduction and Background Sociopolitical violence is a tremendous social problem, given its capacity to spiral into outcomes of moral evil (i.e., intentional severe harm to others). -

Utopian Visions of Family Life in the Stalin-Era Soviet Union

Central European History 44 (2011), 63–91. © Conference Group for Central European History of the American Historical Association, 2011 doi:10.1017/S0008938910001184 Utopian Visions of Family Life in the Stalin-Era Soviet Union Lauren Kaminsky OVIET socialism shared with its utopian socialist predecessors a critique of the conventional family and its household economy.1 Marx and Engels asserted Sthat women’s emancipation would follow the abolition of private property, allowing the family to be a union of individuals within which relations between the sexes would be “a purely private affair.”2 Building on this legacy, Lenin imag- ined a future when unpaid housework and child care would be replaced by com- munal dining rooms, nurseries, kindergartens, and other industries. The issue was so central to the revolutionary program that the Bolsheviks published decrees establishing civil marriage and divorce soon after the October Revolution, in December 1917. These first steps were intended to replace Russia’s family laws with a new legal framework that would encourage more egalitarian sexual and social relations. A complete Code on Marriage, the Family, and Guardianship was ratified by the Central Executive Committee a year later, in October 1918.3 The code established a radical new doctrine based on individual rights and gender equality, but it also preserved marriage registration, alimony, child support, and other transitional provisions thought to be unnecessary after the triumph of socialism. Soviet debates about the relative merits of unfettered sexu- ality and the protection of women and children thus resonated with long-standing tensions in the history of socialism. I would like to thank Atina Grossmann, Carola Sachse, and Mary Nolan, as well as the anonymous reader for Central European History, for their comments and suggestions. -

A Matter of Comparison: the Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity an Analysis and Overview of Comparative Literature and Programs

O C A U H O L S T L E A C N O N I T A A I N R L E T L N I A R E E M C E M B R A N A Matter Of Comparison: The Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity An Analysis And Overview Of Comparative Literature and Programs Koen Kluessien & Carse Ramos December 2018 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance A Matter of Comparison About the IHRA The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is an intergovernmental body whose purpose is to place political and social leaders’ support behind the need for Holocaust education, remembrance and research both nationally and internationally. The IHRA (formerly the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research, or ITF) was initiated in 1998 by former Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson. Persson decided to establish an international organisation that would expand Holocaust education worldwide, and asked former president Bill Clinton and former British prime minister Tony Blair to join him in this effort. Persson also developed the idea of an international forum of governments interested in discussing Holocaust education, which took place in Stockholm between 27–29 January 2000. The Forum was attended by the representatives of 46 governments including; 23 Heads of State or Prime Ministers and 14 Deputy Prime Ministers or Ministers. The Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust was the outcome of the Forum’s deliberations and is the foundation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The IHRA currently has 31 Member Countries, 10 Observer Countries and seven Permanent International Partners. -

Conceptualising Historical Crimes

Should crimes committed in the course of Conceptualising history that are comparable to genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes be Historical Crimes referred to as such, whatever the label used at the time?180 This is the question I want to examine below. Let us compare the prob- lems of labelling historical crimes with his- torical and recent concepts, respectively.181 Historical concepts for historical crimes “Historical concepts” are terms used to de- scribe practices by the contemporaries of these practices. Scholars can defend the use of historical concepts with the argu- ment that many practices deemed inadmis- sible today (such as slavery, human sacri- fice, heritage destruction, racism, censor- ship, etc.) were accepted as rather normal and sometimes even as morally and legally right in some periods of the past. Arguably, then, it would be unfaithful to the sources, misleading and even anachronistic to use Antoon De Baets the present, accusatory labels to describe University of Groningen them. This would mean, for example, that one should not call the crimes committed during the Crusades crimes against hu- manity (even if a present observer would have good reason to qualify some of these crimes as such), for such a concept was nonexistent at the time. A radical variant of the latter is the view that not only recent la- bels should be avoided but even any moral judgments of past crimes. This argument, however, can be coun- tered with several objections. First, diverg- ing judgments. It is well known that parties V HISTOREIN OLU M E 11 (2011) involved in violent conflicts label these conflicts differently. -

The Khmelnytsky Uprising Was a Cossack Rebellion in Ukraine Between the Years 1648–1657 Which Turned Into a Ukrainian War of Liberation from Poland

The Khmelnytsky Uprising was a Cossack rebellion in Ukraine between the years 1648–1657 which turned into a Ukrainian war of liberation from Poland. Under the command of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky , the Cossacks [warrior caste] allied with the Crimean Tatars, and the local peasantry, fought several battles against forces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The result was an eradication of the control of the Polish and their Jewish intermediaries. Between 1648 and 1656, tens of thousands of Jews—given the lack of reliable data, it is impossible to establish more accurate figures—were killed by the rebels, and to this day the Khmelnytsky uprising is considered by Jews to be one of the most traumatic events in their history . The losses inflicted on the Jews of Poland during the fatal decade 1648-1658 were appalling. In the reports of the chroniclers, the number of Jewish victims varies between one hundred thousand and five hundred thousand…even exceeding the catastrophes of the Crusades and the Black Death in Western Europe. Some seven hundred Jewish communities in Poland had suffered massacre and pillage . In the Ukrainian cities situated on the left banks of the Dnieper, the region populated by Cossacks... the Jewish communities had disappeared almost completely . In 1 the localities on the right shore of the Dneiper or in the Polish part of the Ukraine as well as those of Volhynia and Podolia, wherever Cossacks had made their appearance, only about one tenth of the Jewish population survived . http://www.holocaust-history.org/questions/ukrainians.shtml Our research shows that a significant portion of the Ukrainian population voluntarily cooperated with the invaders of their country and voluntarily assisted in the Holocaust. -

Stalin's Loyal Executioner: People's Commissar Nikolai Ezhov, 1895-1940

INDEX adoption, 121 arrest(s), 63 Afanas’ev, N. P., 187–89 arbitrary, 92 affairs, 16–17, 23, 123, 166–68, 172–74, army, 70, 206 185, 198, 200 from Central Committee, 72, 75, 77, 124, Agranov, Ia. S., 23, 45, 55–56, 60, 62, 68, 234n110 73, 84 from Communist Party, 37, 43, 75, 101, agriculture, 249n35 103, 105, 127, 130, 139–40, 146, 148, academy of, 16 151–52, 177–78, 205–6, 222n64, collectivization, 14 233n77 People’s Commissariats of, 13, 76, 146 competitions for number of, 92–93 saboteurs of, 76, 233n106 of Ezhov, 164, 181–82 albums, 136–37 mass, 79, 83, 85, 87, 89–91, 94–95, 99, Alekhin, M. S., 56, 68, 152 103–5, 137–38, 205–6, 237n46 Aleksandrovskii, M. K., 66, 67 of Mensheviks, 74–75 anarchists, 75 of military intelligence, 65–66 Andreev, Andrei, 26, 43photo, 72, 92, 100, new policy for, 156–57 108, 117, 140photo, 164, 175, 176 of NKVD officers, 61–62, 64–65, 78, 83– anti-intellectuals, 8, 202 84, 133, 135–36, 137, 144, 148, 152, Anvelt, Jan, 72 165–66, 168, 183–86, 192, 229n49, army 258n68 demobilized from, 8 political e´migre´s, foreign influences, 41– duty, 3, 5, 6–8 42, 94–95, 99, 101, 205–6, 237n46 purge of, 69–70, 75, 205 quotas of, 84–85, 89–91, 109, 131, 133, reprimand in, 7–8 135, 205–6 .......................... 9199$$ INDX 02-05-02 16:04:35 PS 264 Index of Rightists, 59 Bokii, G. I., 61, 64 small resistance of mass, 102 Bolsheviks, 6, 70, 105, 111, 125, 136, 195 of Socialist Revolutionaries (SR), 74 Bronkowski, B., 40 of Water Transportation, 152 Bukharin, N. -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Employment in Poland 2009 Entrepreneurship for Work

Employment in Poland 2009 Entrepreneurship for work Edited by Maciej Bukowski Warsaw 2010 Authors Editor: Maciej Bukowski, PhD Part I Maciej Bukowski, PhD Piotr Lewandowski Part II Sonia Buchholtz Łukasz Skrok Part III Jan Gąska Piotr Lewandowski Part IV Maciej Bukowski, PhD Horacy Dębowski Co-operation: Maciej Lis, Maciej Małysz, Andrzej Żurawski All opinions and conclusions included in this publication constitute the authors’ views and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy. This report was prepared as part of the project Analysis of the labour market processes and social integration in Poland in the context of economic policy carried out by the Human Resources Development Centre, co-fi nanced by the European Social Fund and initiated by the Department of Economic Analyses and Forecasts at the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, by: Institute for Structural Research (Instytut Badań Strukturalnych) Rejtana 15, r. 24/25 02-516 Warszawa, Poland e-mail: [email protected] www.ibs.org.pl Reytech Rejtana 15, r. 25 02-516 Warszawa, Poland e-mail: [email protected] www.reytech.pl Field survey: ASM Market Research and Analysis Centre Ltd. Grunwaldzka 5, 99-301 Kutno Cover design, typesetting and editing graphic studio Temperówka www.temperowka.pl This publication was co-fi nanced by the European Union under the European Social Fund © Copyright by Human Resources Development Centre ISBN: 978-83-61638-17-9 5 Introduction 7 Part I Labour market in the business cycle 41 Part II Quality of working life – traditional and modern sectors of the economy 91 Part III Procedures and regulations – on hirings and dismissals 131 Part IV Social dialogue in the changing labour market 177 Recommendations for social and economic policy 181 Methodological Appendix 193 Bibliography Introduction The report ‘Employment in Poland 2009 – Entrepreneurship for Work’ is the fi fth edition of the Employment in Poland series, a thorough study of the most signifi cant processes occurring in the Polish and European labour markets. -

Annual Policy Report 2008

Annual Policy Report 2008 produced by the European Migration Network March 2011 The purpose of EMN Annual Policy Reports is to provide an overview into the most significant political and legislative (including EU) developments, as well as public debates, in the area of asylum and migration, with the focus on third-country nationals rather than EU nationals. This EMN Synthesis Report summarises the main findings of National Reports produced by twenty-three of the EMN National Contact Points (EMN NCPs) from Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The EMN Synthesis Report, as well as the twenty-three National Reports upon which the synthesis is based, may be downloaded from http://emn.intrasoft- intl.com/Downloads/prepareShowFiles.do;?entryTitle=02. Annual Policy Report 2008 Several of the National Reports are also available in the Member States‟ national language, as well as in English. EMN Synthesis Report – Annual Policy Report 2008 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Methodology followed ........................................................................................ 7 2. POLITICAL AND INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS ........................................ 9 2.1 General political developments ...........................................................................