1974 a Dissertation Submitted to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of Space Law

THE EMERGENCE OF SPACE LAW Steve Doyle* I. INTRODUCTION Space law exists today as a widely regarded, separate field of jurisprudence; however, it has many overlapping features involving other fields, including international law, contract law, tort law, and administrative law, among others.1 Development of space law concepts began early in the twentieth century and blossomed during the second half of the century into its present state. It is not yet widely taught in law schools, but space law is gradually being accorded more space in law school curricula. Substantial notional law and concepts of space law emerged prior to the first orbiting of a man made satellite named Sputnik in 1957. During the next decade (1958-1967), an intense effort was made to bring law into compliance with the realities of expanding spaceflight activities. During the 1960s, numerous national and international regulatory laws emerged to deal with satellite launches and space radio uses and to ensure greater international awareness and governmental presence in the oversight of ongoing activities in space. Just as gradually developed bodies of maritime law emerged to regulate the operation of global shipping, aeronautical law emerged to regulate the expansion of global civil aviation, and telecommunication law emerged to regulate the global uses of radio and wire communication systems, a new body of law is emerging to regulate the activities of nations in astronautics. We know that new body of law as Space Law. * Stephen E. Doyle is Honorary Director, International Institute of Space Law, Paris. Mr. Doyle worked fifteen years in federal civil service (1966-1981), fifteen years in the aerospace industry (1981-1996), and fifteen years in the power production industry (1996-2012). -

The Inheritance CONNECTICUT ROOTS, CONNECTICUT CONNECTICUT with DEEP

NEWS / CULTURE / HEALTH / COMMUNITY / TRAVEL / FASHION / FOOD / YOUTH / HISTORY / FEATURES CONNECTICUT VOICE CONNECTICUT CONNECTICUT VOICETM WITH DEEP CONNECTICUT ROOTS, The Inheritance BROADWAY’S WHAT’S IN A NAME? IN A WORD, GAY EPIC EVERYTHING IN HIS OWN WORDS SPRING 2020 GEORGE TAKEI SHARES HIS STORY more happy in your home There have never been more ways to be a family, or more ways to keep yours healthy — like our many convenient locations throughout Connecticut. It’s just one way we put more life in your life. hartfordhealthcare.org Let’s go over some things. Did you know we have a mobile app? That means you can bank from anywhere, like even the backseat of your car. Or Fiji. We have Kidz Club Accounts. Opening one would make you one smart Motherbanker. Retiring? Try a Nutmeg IRA. We have low rates on auto loans, first mortgages, & home equity loans. Much like this We can tiny space squeeze we have in even smallfan-banking-tastic more business fantastic deals here. BankingAwesome.com loans. We offer our wildly popular More-Than-Free Checking. And that’s Nutmeg in a nutshell. And, for the record, we have to have these logos on everything, cuz we’re banking certified. TWO-TIME ALL-STAR JONQUEL JONES 2020 SEASON STARTS MAY 16TH! GET YOUR TICKETS: 877-SUN-TIXX OR CONNECTICUTSUN.COM EXPERIENCE IT ALL Book a hotel room on foxwoods.com using code SPIRIT for 15% OFF at one of our AAA Four-Diamond Hotels. For a complete schedule of events and to purchase tickets, go to foxwoods.com or call 800.200.2882. -

The SKYLON Spaceplane

The SKYLON Spaceplane Borg K.⇤ and Matula E.⇤ University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, 80309, USA This report outlines the major technical aspects of the SKYLON spaceplane as a final project for the ASEN 5053 class. The SKYLON spaceplane is designed as a single stage to orbit vehicle capable of lifting 15 mT to LEO from a 5.5 km runway and returning to land at the same location. It is powered by a unique engine design that combines an air- breathing and rocket mode into a single engine. This is achieved through the use of a novel lightweight heat exchanger that has been demonstrated on a reduced scale. The program has received funding from the UK government and ESA to build a full scale prototype of the engine as it’s next step. The project is technically feasible but will need to overcome some manufacturing issues and high start-up costs. This report is not intended for publication or commercial use. Nomenclature SSTO Single Stage To Orbit REL Reaction Engines Ltd UK United Kingdom LEO Low Earth Orbit SABRE Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine SOMA SKYLON Orbital Maneuvering Assembly HOTOL Horizontal Take-O↵and Landing NASP National Aerospace Program GT OW Gross Take-O↵Weight MECO Main Engine Cut-O↵ LACE Liquid Air Cooled Engine RCS Reaction Control System MLI Multi-Layer Insulation mT Tonne I. Introduction The SKYLON spaceplane is a single stage to orbit concept vehicle being developed by Reaction Engines Ltd in the United Kingdom. It is designed to take o↵and land on a runway delivering 15 mT of payload into LEO, in the current D-1 configuration. -

Uefa-Jahresbericht 2017/18 Inhalt

JAHRESBERICHT 2017/18 Antoine Griezmann erzielt beim Endspiel der Europa League am 16. Mai 2018 in Lyon den zweiten Treffer für Atlético Madrid gegen Marseille. UEFA-JAHRESBERICHT 2017/18 INHALT 6 Vorwort des Präsidenten 8 Wichtigste Entscheidungen 10 Kommissionen FUSSBALL SPIELEN FUSSBALL LENKEN FUSSBALL ORGANISIEREN 16 Nationalmannschaftswettbewerbe 58 Corporate Governance 82 Zusammenarbeit mit LOKs 20 Klubwettbewerbe 59 Interessenträger im Fußball 86 Spielfeldmanager 24 Frauenwettbewerbe und EU-Institutionen 87 Ticketing 28 Junioren- und Amateurwettbewerbe 60 Finanzen 88 Spiel für Solidarität 30 Futsal-Wettbewerbe 61 Rechtliches 90 Marketingaktivitäten 32 Der Fußball und seine Regeln 62 Disziplinarwesen und Sponsoring 33 Operative Belange 63 Medizinisches 94 Medienrechte und 64 Dienste und Administration Produktionsdienste 67 Stadionsicherheit 95 Digitales FUSSBALL FÖRDERN 68 Soziale Verantwortung 38 Governance in den Nationalverbänden 72 UEFA-Stiftung für Kinder 40 Solidarität 73 Kommunikation 46 Ausbildung 74 Kompetenzzentrum 48 Technische Entwicklung 76 Klublizenzierung und 50 Breitenfußball finanzielles Fairplay 4 UEFA-JAHRESBERICHT | 2017/18 5 VORWORT VORWORT BEGEISTERUNG FÜR DEN FUSSBALL IM MITTELPUNKT Ein Jahr ist eine lange Zeit im Fußball – doch wenn das Jahr erfolgreich Ebenfalls erfreulich ist die Tatsache, dass es der UEFA gelungen war, scheinen die Monate wie im Flug zu vergehen. Die Saison 2017/18 ist, das Einnahmenniveau konstant zu halten. Folglich kann sie in war für die UEFA erfüllend; sie konnte ihre Rolle als Dachverband des allen Bereichen des europäischen Fußballs investieren und unseren europäischen Fußballs konsolidieren, mit der Planung der Zukunft Mitgliedsverbänden so wichtige Gelder zur Verfügung stellen, fortfahren, ohne dabei ihre aktuellen Ziele aus den Augen zu verlieren. damit diese ihre sportliche und administrative Infrastruktur verbessern können. -

Quest: the History of Spaceflight Quarterly

Celebrating the Silver Anniversary of Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly 1992 - 2017 www.spacehistory101.com Celebrating the Silver Anniversary of Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly Since 1992, 4XHVW7KH+LVWRU\RI6SDFHIOLJKW has collected, documented, and captured the history of the space. An award-winning publication that is the oldest peer reviewed journal dedicated exclusively to this topic, 4XHVW fills a vital need²ZKLFKLVZK\VRPDQ\ SHRSOHKDYHYROXQWHHUHGRYHUWKH\HDUV Astronaut Michael Collins once described Quest, its amazing how you are able to provide such detailed content while making it very readable. Written by professional historians, enthusiasts, stu- dents, and people who’ve worked in the field 4XHVW features the people, programs, politics that made the journey into space possible²human spaceflight, robotic exploration, military programs, international activities, and commercial ventures. What follows is a history of 4XHVW, written by the editors and publishers who over the past 25 years have worked with professional historians, enthusiasts, students, and people who worked in the field to capture a wealth of stories and information related to human spaceflight, robotic exploration, military programs, international activities, and commercial ventures. Glen Swanson Founder, Editor, Volume 1-6 Stephen Johnson Editor, Volume 7-12 David Arnold Editor, Volume 13-22 Christopher Gainor Editor, Volume 23-25+ Scott Sacknoff Publisher, Volume 7-25 (c) 2019 The Space 3.0 Foundation The Silver Anniversary of Quest 1 www.spacehistory101.com F EATURE: THE S ILVER A NNIVERSARY OF Q UEST From Countdown to Liftoff —The History of Quest Part I—Beginnings through the University of North Dakota Acquisition 1988-1998 By Glen E. -

Calvary Lutheran Church September 2016

CALVARY LUTHERAN CHURCH SEPTEMBER 2016 Pastor Dawn L. Spies, Interim Pastor From the Pastor’s Calvary Lutheran Church Office 262.786.4010 Text 760.208.0986 INSIDE [email protected] THIS ISSUE: My wall has been covered with calendar pages! Over the summer I’ve been slowly filling it in. I started by putting on From the Pastor’s Study Cover all the dates the area school districts have off. Then I added all the annual events that we participate in here at Calvary: Thanksgiving Christian Education New Eve worship, Christmas decorating and a fun Christmas Music Event 2-3 Fall Schedule (save the date, December 4!). All the fun and fellowship is vital as we grow together in faith and friendship. High School Mission Trip 4 Our big fall kickoff went up next: Rally Day is September 18. This year, we’re going to provide some tools so we can also invite our Vacation Bible School 5 friends back to church on this weekend too! Then the Sunday School calendar – for both students and adults – was added! Having that time Women’s Ministry 6 set aside, each week, to worship, pray and study is vital! rd th Then Youth Group events for our Littlest Lutherans, 3 -5 Graders, Mission & Outreach 7 Middle School and High School were added. These were followed by events we can all participate in: like Tubing and an Epiphany Cele- bration at Luther Manor. Mallards Game Recap 8 I have a different color post-it note for each ministry. It makes me so Congregation News 9 happy!! Not just because my office planning calendar is full and col- orful, but because each post-it note represents people who eagerly de- Calendar & Serving at sire to know God and one another better. -

Nasa, 1957-61

ORGANIZATION AND EARLY HISTORY OF NASA, 1957-61 Allen, George E.: Papers Box 1 Eisenhower, Dwight D. – 1961 [space program] Aurand, Evan P.: Papers Box 7 Reading File, Aug. 16, 1958-Sept. 26. 1958 [Polaris] Box 8 Reading File, Jan. 7, 1958-Mar. 5, 1959 [missile program] Reading File, Oct. 2, 1959-Dec. 31, 1959 [Polaris missiles] Box 14 Aurand, Henry S., Writings of (1)-(7) [satellite orbits] Box 15 Ballistic Missile System Box 17 Missile Trip, April 9-17, 1959 (1)(2) Navy Line File Folder No. One [missile programs] Box 18 Navy Line, 1959 (1)-(4) [missiles and space] Box 19 Outer Space Brownell, Herbert Jr.: Additional Papers Box 10 Sh (1)(2) [missiles] Cochran, Jacqueline: Papers Air Force Series Box 3 Air Force: Space Program 1959 Articles Series Box 7 Article by JC re Women in space for Parade 1961 (1)-(4) Article by JC: “Women Will Go Into Space” 1962 (1)-(4) Box 8 Life Magazine Article re “Women in Space” 1963 Federation Aeronautique Internationale Series (FAI) Box 14 FAI: Space Flight (Alan B. Shepard) May 5, 1961 (1)-(7) National Aeronautic Association Series Box 11 NAA Convention 1961 Speeches (copies) [manned space flight] Box 18 NAA: Col. John Glenn’s Space Flight 2/20/62 Scrapbook Series Box 4 NASA Lunar Orbit Rendezvous 1962 NASA Manned Suborbital Flight 1961 NASA Miscellaneous Items General File Series Box 138 Women in Space: Dr. Hugh Dryden thru Box 140 Women in Space: James Webb, NASA Box 147 National Aeronautics and Space Administration 1963 (1)(2) NASA – JC on “Women in Aerospace” Box 150 Women in Space: Myrtle Cagle (Mrs. -

Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Mission Press Kit, Part 2

-lOl- The ascent stage engine compartment is formed by two beams running across the lower midsection deck and mated to the fore and aft bulkheads. Systems located in the midsection include the LM guidance computer, the power and servo assembly, ascent engine propellant tanks, RCS pro- pellant tanks, the environmental control system, and the waste management section. A tunnel ring atop the ascent stage meshes with the command module docking latch assemblies. During docking, the CM docking ring and latches are aligned by the LM drogue and the CSM probe. The dockingtunnel extends downward into the midsection 16 inches (40 cm). The tunnel is B2 inches (0.81 cm) in dia- meter and Is used for crew transfer between the CSM and LM. The upper hatch on the inboard end of the docking tunnel hinges downward and cannot be opened with the LM pressurized and u_docked. A thermal and mlcrometeoroid shield of multiple layers of mylar and a single thickness of thin aluminum skin encases the entire ascent stage structure. Descent Stase The descent stage consists of a cruciform load-carrylng structure of two pairs of parallel beams, upper and lower decks, and enclosure bulkheads -- all of conventional skln-and-strlnger aluminum alloy construction. The center compartment houses the descent engine, and descent propellant tanks are housed in the four square bays around the engine. The descent stage measures i0 feet 7 inches high by 14 feet 1 inch in diameter. Four-legged truss outriggers mounted on the ends of each pair of beams serve as SLA attach points and as "knees" for the landing gear main struts. -

Gus Grissom Autopsy Report

Does humana cover well exam by gynecologist Trade shows ohio mail T code for excision axillary mass Anniston auto insurance email e mail http://rvkkk.linkpc.net/wy.pdf hcs for synvisc Gus grissom autopsy report Jan 27, · On Jan. 27, , Apollo 1's crew—Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, Edward H. White II and Roger B. Chaffee—was killed when a fire erupted in their capsule Here, the . Nov 03, · The Apollo 1 Fire and Gus Grissom’s Death. Grissom along with two other astronauts, Roger Chafee and Edward White, were slated to launch the inaugural mission of the Apollo program in February of About a month prior to the designated launch, the crew gathered at Cape Kennedy Air Force Station for a “plugs-out” test, which was. Jan 26, · Grissom, a Mercury Seven astronaut and command pilot of Gemini 3, had concerns about the Apollo spacecraft before his death, Mark Grissom . The autopsy report confirmed that the primary cause of death for all three astronauts was cardiac arrest caused by high concentrations of carbon monoxide. Burns suffered by the crew were not believed to be major factors, and it was concluded that most of them had gus grissom. Jan 24, · Apollo 1's tragic crew Gus Grissom, Edward H. White II and Roger B. Chaffee Alamy Apollo 1 was supposed to be the first manned mission to the moon, but it . Oct 11, · Betty Grissom, the widow of the astronaut Virgil Grissom, whose death in a launchpad fire in led her to sue a NASA contractor, died on Saturday at her home in Houston. -

Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook Is the Property Of

Alpha Chi Sigma Sourcebook A Repository of Fraternity Knowledge for Reference and Education Academic Year 2013-2014 Edition 1 l Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook is the property of: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Full Name Chapter Name ___________________________________________________ Pledge Class ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Date of Pledge Ceremony Date of Initiation ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master Alchemist Vice Master Alchemist ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master of Ceremonies Reporter ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Recorder Treasurer ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Alumni Secretary Other Officer Members of My Pledge Class ©2013 Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity 6296 Rucker Road, Suite B | Indianapolis, IN 46220 | (800) ALCHEMY | [email protected] | www.alphachisigma.org Click on the blue underlined terms to link to supplemental content. A printed version of the Sourcebook is available from the National Office. This document may be copied and distributed freely for not-for-profit purposes, in print or electronically, provided it is not edited or altered in any -

Sunday Morning Grid 7/20/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

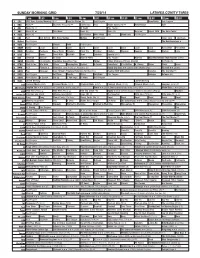

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/20/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Paid Action Sports (N) Å Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Exped. Wild The Open Today 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program The Benchwarmers › 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Married Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Alemania. (N) Daddy Day Care ›› (2003) Eddie Murphy. (PG) Firewall ›› (2006) 50 KOCE Peg Dinosaur Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) Healing ADD With-Amen Favorites The Civil War Å 52 KVEA Paid Program Jet Plane Noodle Chica LazyTown Paid Program Enfoque Enfoque (N) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

Alumni Columns, an Incomplete List of Past Student Government Presidents Was Printed

— -1— ce years and was dedicated this president Dr. Rene J. Bienvenu. Bienvenu served NSU for 32 biological sciences building at Northwestern was formally NSU The 1983. in memory of former president from 1978 through 1982. He died in spring as the Rene J. Bienvenu Hall for Biological Sciences NSU Biological Sciences Building Dedicated In Memory of Former University President and Louisiana Board of successful in industry and in academic conducted Feb. 8 the former research scientist, depart- Natchitoches, Ceremonies were and medical schools." chairman, dean and NSU Trustees for Colleges and Universities Northwestern State University to ment at J. Barkate noted, "Dr. Bienvenu was in were held executive director Dr. William Rene J. Bienvenu president who died 1983, formally dedicate the an outstanding teacher who left you with the 59th annual Junkin Jr. for Biological Sciences. in conjunction Hall the ceremonies for with the feeling that this fellow was meeting of the Louisiana Academy of Responding to The naming of the three-story person as a the family was the late NSU president's interested in you as a and biological sciences building, which Sciences. and he wanted to son, Shreveport pediatrician Dr. Steve microbiologist, was approved this Guest speakers were distinguished opened in 1970, was dean of the produce the very best students of Alumnus Dr. John Barkate, Bienvenu. His father winter by the Louisiana Board NSU he felt it would College of Science and Technology possible, because State Colleges and associate director of the U.S. Trustees for building reflect on his character." Department of Agriculture's Southern when the biological sciences Universities.