Spirit Phd Series 28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inheritance CONNECTICUT ROOTS, CONNECTICUT CONNECTICUT with DEEP

NEWS / CULTURE / HEALTH / COMMUNITY / TRAVEL / FASHION / FOOD / YOUTH / HISTORY / FEATURES CONNECTICUT VOICE CONNECTICUT CONNECTICUT VOICETM WITH DEEP CONNECTICUT ROOTS, The Inheritance BROADWAY’S WHAT’S IN A NAME? IN A WORD, GAY EPIC EVERYTHING IN HIS OWN WORDS SPRING 2020 GEORGE TAKEI SHARES HIS STORY more happy in your home There have never been more ways to be a family, or more ways to keep yours healthy — like our many convenient locations throughout Connecticut. It’s just one way we put more life in your life. hartfordhealthcare.org Let’s go over some things. Did you know we have a mobile app? That means you can bank from anywhere, like even the backseat of your car. Or Fiji. We have Kidz Club Accounts. Opening one would make you one smart Motherbanker. Retiring? Try a Nutmeg IRA. We have low rates on auto loans, first mortgages, & home equity loans. Much like this We can tiny space squeeze we have in even smallfan-banking-tastic more business fantastic deals here. BankingAwesome.com loans. We offer our wildly popular More-Than-Free Checking. And that’s Nutmeg in a nutshell. And, for the record, we have to have these logos on everything, cuz we’re banking certified. TWO-TIME ALL-STAR JONQUEL JONES 2020 SEASON STARTS MAY 16TH! GET YOUR TICKETS: 877-SUN-TIXX OR CONNECTICUTSUN.COM EXPERIENCE IT ALL Book a hotel room on foxwoods.com using code SPIRIT for 15% OFF at one of our AAA Four-Diamond Hotels. For a complete schedule of events and to purchase tickets, go to foxwoods.com or call 800.200.2882. -

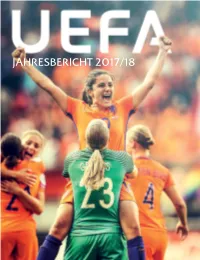

Uefa-Jahresbericht 2017/18 Inhalt

JAHRESBERICHT 2017/18 Antoine Griezmann erzielt beim Endspiel der Europa League am 16. Mai 2018 in Lyon den zweiten Treffer für Atlético Madrid gegen Marseille. UEFA-JAHRESBERICHT 2017/18 INHALT 6 Vorwort des Präsidenten 8 Wichtigste Entscheidungen 10 Kommissionen FUSSBALL SPIELEN FUSSBALL LENKEN FUSSBALL ORGANISIEREN 16 Nationalmannschaftswettbewerbe 58 Corporate Governance 82 Zusammenarbeit mit LOKs 20 Klubwettbewerbe 59 Interessenträger im Fußball 86 Spielfeldmanager 24 Frauenwettbewerbe und EU-Institutionen 87 Ticketing 28 Junioren- und Amateurwettbewerbe 60 Finanzen 88 Spiel für Solidarität 30 Futsal-Wettbewerbe 61 Rechtliches 90 Marketingaktivitäten 32 Der Fußball und seine Regeln 62 Disziplinarwesen und Sponsoring 33 Operative Belange 63 Medizinisches 94 Medienrechte und 64 Dienste und Administration Produktionsdienste 67 Stadionsicherheit 95 Digitales FUSSBALL FÖRDERN 68 Soziale Verantwortung 38 Governance in den Nationalverbänden 72 UEFA-Stiftung für Kinder 40 Solidarität 73 Kommunikation 46 Ausbildung 74 Kompetenzzentrum 48 Technische Entwicklung 76 Klublizenzierung und 50 Breitenfußball finanzielles Fairplay 4 UEFA-JAHRESBERICHT | 2017/18 5 VORWORT VORWORT BEGEISTERUNG FÜR DEN FUSSBALL IM MITTELPUNKT Ein Jahr ist eine lange Zeit im Fußball – doch wenn das Jahr erfolgreich Ebenfalls erfreulich ist die Tatsache, dass es der UEFA gelungen war, scheinen die Monate wie im Flug zu vergehen. Die Saison 2017/18 ist, das Einnahmenniveau konstant zu halten. Folglich kann sie in war für die UEFA erfüllend; sie konnte ihre Rolle als Dachverband des allen Bereichen des europäischen Fußballs investieren und unseren europäischen Fußballs konsolidieren, mit der Planung der Zukunft Mitgliedsverbänden so wichtige Gelder zur Verfügung stellen, fortfahren, ohne dabei ihre aktuellen Ziele aus den Augen zu verlieren. damit diese ihre sportliche und administrative Infrastruktur verbessern können. -

Ministry of Justice Folketinget the Legal Affairs Committee Christiansborg 1240 Copenhagen K Date: 10 March 2011 Office: Civil and Police Dept

The Legal Affairs Committee 2010-11 REU ordinary part, final answer to Question no. 604 Public Ministry of Justice Folketinget The Legal Affairs Committee Christiansborg 1240 Copenhagen K Date: 10 March 2011 Office: Civil and Police Dept. Case no.: 2011-150-2151 Doc.: JEE44087 We forward herewith the answer to Question no. 604 (ordinary part) that the Danish Parliament's Legal Affairs Committee submitted to the Minister for Justice on 11 February 2011. The question was asked at the request of Line Barfod (The Unity List – the Red-Green Alliance). Lars Barfoed Carsten Kristian Vollmer Slotsholmsgade 10 1216 Copenhagen K. Telephone 7226 8400 Fax 3393 3510 www.justitsministeriet.dk [email protected] Question no. 604 (ordinary part) from the Danish Parliament's Legal Affairs Committee: “What training are judges, solicitors, public prosecutors, the police force and the immigration authorities given to enable them to identify and help victims of human trafficking in the best possible manner?” Answer: In order to answer this question, the Ministry of Justice obtained statements from the Danish Court Administration, the National Commission of the Danish Police, the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs. The Danish Court Administration provided the following information: “Judges and other practising lawyers receive training in “handling” injured parties, including the victims of human trafficking in order to enable them to identify and help victims of criminality in general. This training forms part of the ordinary course of education and further education for judges and other practising lawyers. The Danish Court Administration can also inform you that the complexity of cases involving human trafficking was most recently reviewed and discussed in November 2010 at the Judicial Training Centre (Domstolsakademiet), which provides further education for judges and practising lawyers. -

( J Lanttoftler

! torch 30, 1950 cal advertisers 80 « are only three ilneai, the Citizen* * Hatchery, and €\)nH xm vt\) (Jlanttoftler king stored grain The Forrest News Was Consolidated With The Plaindealer as of December 25, 1947 at temperature* m F. and multiply emperatures above SEVENTY-SEVENTH YEAR CHATSWORTH, ILLINOIS, THURSDAY, APRIL 6, 1950 NO. 32 AUTHOR OF HISTORY OF CHATSWORTH Gillum Ford Qnb Members Air Ed ig ra p h s — Farmer City, Odell, Buried In Minonk Lots of Water Goes Louis J. Haberkom, Long-time Cemetery Monday Theatre If certain predictions are Through Meters r, Il l i n o i s Views At Dinner Merchant, Is Claimed By Death true about this year’s lessen Fairbury Approve Gillum Ford, 69, a resident of - ing income, we may return to Chatsworth community 20 years March M the wartime measure of sopping ago, died at his home near Minonk Meeting Last Week Louis J. Haberkom, 88, died at up the gravy. Bond Issues Saturday morning. He had been In Chatsworth THIS WEEK his home In Chatsworth Friday •k in declining health for several afternoon about 4 o’clock. Death Have you ever noticed how years and died in his sleep. Reynolds Factory Members Side-step was due primarily to age. He had often a helping hand is ex Gibson City Voters Funeral services were held in w y e s la Daylight Time and been confined to his home for sev tended empty-handed ? the Minonk Presbyterian church Uses About Half eral weeks but he often said he ■k Turn Down Hard Monday afternoon at 2 o’clock andled?* Evening Openings did not have an ache or pain and Honor the man who neither Sewage Bonds with burial in the Minonk ceme The Water Pumped his mind remained keen almost to brags about his yesterdays or tery. -

T T LJ I Republic/Universal's Flaw Sees C R E a T O R O F a L

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw a zW MA!' THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT, JUNE 22, 2002 BMG's Zomba Buy Sets Calder Free As BMG Absorbs Mandatory Deal, Industry Ponders Zomba Co- Founder's Plans BY GORDON MASSON Calder for more than 30 years, corn- ness," one former Calder associate LONDON-While the music industry ments, "I've always found it ex- notes. "Whatever he does next, I'm comes to terms with Zomba chair - tremely difficult to think of Clive not sure it'll be a phenomenal success." man/CEO Clive Calder's decision to sell doing anything. Having known him Calder was unavailable for com- out to BMG and the resulting mam- since the 1960s and having worked ment, but in a statement he said: moth payout, the most intrigu- "With its outstanding execu- ing part of the news for many tives and creative talent, Zom- lies in what the reclusive South SMG ba should add a lot of value to African plans to do next. With a Bertelsmann's music division, reputed $2.8 billion check soon BMG. While the exercise of heading his way from Bertelsmann's with him all those years, I can't this option will undoubtedly be a German headquarters in Gütersloh, believe he'll do nothing. But I don't surprise to many in the music Calder is not exactly in need of a job. have any idea what would be in his industry, this is a natural culmina- But those who know the man do not mind -I guess that's going to exer- tion of many years of close business believe he is about to simply retire. -

ATR Issue 10.Pmd

Issue 10, April 2018 ISSN: 2286-7511 EISSN: 2287-0113 Special Issue–Life after Trafficking Editorial: Moving Forward—Life after trafficking Consuming Life after Anti-Trafficking Vulnerable Here or There? Examining the vulnerability of victims of human trafficking before and after return Dilemmas in Rescue and Reintegration: A critical assessment of India’s policies for children trafficked for labour exploitation At Home: Family reintegration of trafficked Indonesian men From Passive Victims to Partners in Their Own Reintegration: Civil society’s role in empowering returned Thai fishermen Life after Trafficking in Azerbaijan: Reintegration experiences of survivors Family Separation, Reunification, and Intergenerational Trauma in the Aftermath of Human Trafficking in the United States ‘There are no Victims Here’: Ethnography of a reintegration shelter for survivors of trafficking in Bangladesh Short articles section The New Life: Construction sites and mine fields Trafficked Women in Denmark—Falling through the cracks Life after Trafficking: A gap in the UK’s modern slavery efforts In Their Own Words… ATR issue 10.pmd 1 1/1/2545, 0:32 anti reviewtrafficking GUEST EDITORS EDITOR DENISE BRENNAN BORISLAV GERASIMOV SINE PLAMBECH EDITORIAL BOARD RUTVICA ANDRIJASEVIC, University of Bristol, United Kingdom JACQUELINE BHABHA, Harvard School of Public Health, United States URMILA BHOOLA, UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, including its causes and consequences, South Africa XIANG BIAO, Oxford University, United Kingdom LUCIANA -

New York State Resident Is Appointed Fire Director

j! | SERVICE CLUB CHAMPS - New on behalf of the Rotarians is Tom Miller. HERALD TROPHY WINNERS - Bryant W. Griffin, president of the PRIZE SPECIMENS - Some of the Bryant W. Griffin, chamber president; Ed Providence Mayor Edward Bien Is shown as Looking on are F. James Schneider and Carl Summit Area Chamber of Commerce presents the annual Summit Herald catehes made during the Summit Area Kaus, outing co-chairman; Buss Baiter, Jtoe T he presented tile Service Club Golf Trophy Huus. Not included in the photo, but a Golf Trophy to the CIBA-GEIGY team, this year's winner, during the an- Chamber of Commerce's annual fish-golf Edwards and Ken Johnston, chairman of to members of the Rotary Club, who copped member of the winning team Is Ed Heft. nual summer outing held last Friday at the Maplewood Country Club. With outing held last Friday are proudly the fishing contingent. The day-Ing affair this year's service dob golf honors during More than 150 were on hand for the annual Mr. Griffin, and with their scores are Don Coombs, 79; Dr. Robert Bow- displayed by some who left shortly after at Maplewood Country Clnb was highlighted the Summit Area Chamber of Commerce outing held this year at theMaplewood man, 76, and Cortney Cromwell, 8C. Missing when the photo was taken was dawn from Atlantic Highlands to try their by dinner and the awarding of various golf outing last Friday. Accepting the trophy Country Club. (Wolin photo) Fred Cooper, who shot a 77. (Wolin photo) hand on the high seas. -

The Nest-STOP Trafficking's Work Combating Trafficking in Women in Denmark

The Nest-STOP Trafficking’s Work Combating Trafficking in Women in Denmark Background Since 1990 we have witnessed a sharp increase in the number of women in prostitution in Denmark, rising from an estimated 1,700 in 1990, to at least 4,270 in 2006. At the same time we have seen an increase in the number of foreign women on the street and in the approximately 700 brothels and massage parlours in Denmark. It is clear that there are women in Denmark who have been trafficked. It is estimated that three quarters of the women in prostitution on the streets of Vesterbro in Copenhagen are foreign, and that at least half of the women in prostitution in brothels are foreign. Prostitution is not illegal in Denmark, but it is not considered an occupation. Neither is it illegal to purchase prostitution services in Denmark, though it is illegal - and punishable - to purchase prostitution from young persons under the age of 18. Foreign women in prostitution in Denmark are therefore not arrested by the police for prostitution, but rather for earning money without a valid work permit, or for residing in the country illegally. In this way women are often deported for working illegally, or for illegal residence, with very short notice. Women who are victims of trafficking are therefore often treated as criminals and deported, with no consideration for their situation, other than the offer of a 15 day delay of their deportation date. Who is RSK? Reden-STOP Kvindehandel (The Nest-STOP Trafficking in Women) is a private institution under the YMCA´s Social Work. -

The Ingham County in Class C Tournament Second Varsity Gaml!

Springport Bindery s.pdngpor.t, Mich • . : I ... , ·, * Winner of 5 major newspaper oxco/.lence ~wa~ds jn 1964'.'.----·~-·------ 3 Sections - 28 Pages Wednesday, March 3, 1965 10<: per copy Mason 5-year-old Will Get Surgery, But Needs Blood In a Mason home today a valescence It Is expected little girl nearing 5 years the child 1s heart will bo of age Is awaiting anXiously normal, for the arrival of April·· The reason for the delay almost as anxiously as before the surgery Is at other little gll•ls her age tempted was at the advice waited for the arrival of of surgeons who told the Santa Claus at Christmas parents they should walt time, until the child Is 5 years But this little girl waits old, That age Is regarded for tho greatest {flft that as the best time to p()r can be bestowed--good form the operation before health and to be able to the child gets Into compe romp and play like other titive play. children, She Is Linda An operation such as this Kerr, daughter of Mr. and calls for considerable Mrs, Ivan Kerr, blood to be administered to THE YOUNGER THE SHOVELER the more the patient. Perhaps those This Mason child has a who read this story will fun he seemed to have. Jeeps, trucks, tractors heart condl.tion. She was see their way clear to visit and people turned out to clear the snow so that life a "blue baby", There Is a the bloodmobile when 11 blocltage of a valve leading visits Mason Friday and could return to norma I. -

Prostitution Policy: Legalization, Decriminalization and the Nordic Model Follow This and Additional Works At

Seattle Journal for Social Justice Volume 14 Issue 2 Fall 2015 Article 10 4-27-2016 Prostitution Policy: Legalization, Decriminalization and the Nordic Model Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj Ane P Mathiesonart of the Administr ative Law Commons, Agriculture Law Commons, Arts and Humanities Commons, EastBankingon Brandanam Finance Law Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Commercial Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Consumer Protection LawAny aCommons Noble , Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Disability Law Commons, Educational Leadership Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Energy and Utilities Law Commons, Family Law Commons, Fourteenth Amendment Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, Housing Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Immigration Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Insurance Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, Legislation Commons, Marketing Law Commons, National Security Law Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Other Education Commons, Other Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, Secured Transactions Commons, Securities Law Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Welfare Law Commons, Transnational Law Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Mathieson, Ane; Branam, Easton; and Noble, Anya (2016) "Prostitution Policy: Legalization, Decriminalization and the Nordic Model," Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Vol. -

Program Schedule

Friday, August 6, 4:30 p.m. 55 Program Schedule equivalence and blockmodels; an introduction to local analysis including The length of each session/meeting activity is one hour dyadic and triadic analyses; and basic distribution theory and statistical and 45 minutes, unless noted otherwise. Session models. presiders and committee chairs should see that sessions The course text will be: Wasserman, Stanley and Faust, Katherine and meetings end on time to avoid conflicts with (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge, ENG and New York: Cambridge University Press. subsequent activities scheduled into the same room. 1999 ASA Chair Conference—Thursday, August 5, 1:00- Program Corrections: The information printed here 9:30 p.m.—Hilton Chicago, Williford C reflects session updates received from organizers through Section on Political Sociology Conference—Thursday, July 12, 1999. Changes received after that date appear in August 5, 1:00-5:00 p.m.—Hilton Chicago, Boulevard the Convention Bulletin distributed with the Final Program Rooms A-B-C packets. Please check that bulletin for the latest updates. Honors Program Orientation—Thursday, August 5, 1:30- 5:30 p.m.—Hilton Chicago, Marquette Pre-Meeting Activities ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ____ Alpha Kappa Delta Executive Council—Thursday, August 5, 8:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m.—Hilton Chicago, Lake Erie Friday, August 6 North American Chinese Sociologists Association conference—Thursday, August 5, 8:30 a.m.-5:30 p.m.— 8:30 a.m. Meetings ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Hilton Chicago, Joliet ____ Add Health National Scientific Advisory Committee— Committee on Nominations (to 4:15 p.m.)—Hilton Chicago, Thursday, August 5, 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m.—Hilton McCormick Room Chicago, Conference Room 4L 1. -

Prostitution

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Prostitution Third Report of Session 2016–17 HC 26 House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Prostitution Third Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 15 June 2016 HC 26 Published on 1 July 2016 by authority of the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) (Chair) Victoria Atkins MP (Conservative, Louth and Horncastle) James Berry MP (Conservative, Kingston and Surbiton) Mr David Burrowes MP (Conservative, Enfield, Southgate) Nusrat Ghani MP (Conservative, Wealden) Mr Ranil Jayawardena MP (Conservative, North East Hampshire) Tim Loughton MP (Conservative, East Worthing and Shoreham) Stuart C. McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Naz Shah MP (Independent, Bradford West) Mr Chuka Umunna MP (Labour, Streatham) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) The following were also members of the Committee during the Parliament. Keir Starmer MP (Labour, Holborn and St Pancras) Anna Turley MP (Labour (Co-op), Redcar) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/homeaffairscom and in print by Order of the House.