John Covach Andrew Flory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joe Louis Walker

Issue #218 LIVING BLUES #218 • APRIL 2012 Vol. 43, #2 ® © JOE LOUIS WA JOE LOUIS L KER - LEE GATES - KER - LEE GATES WALKER K IRK F L ETCHER - R LEE GATES OSCOE C HENIER - PAU KIRK L RISHE FLETCHER LL - 2012 B L UES FESTIVA ROSCOE L GUIDE CHENIER $6.95 US $6.95 CAN www.livingblues.com 2012 Festival Guide Inside! Joseph A. Rosen Rhythm andBluesCruise,Rhythm October 2007. onthe Legendary Joe LouisWalker In 1985, after a decade of playing and singing nothing but gospel music with a quartet called the Spiritual Corinthians, 35-year-old Joe Louis Walker decided to get back to the blues. The San Francisco–born singer-guitarist had begun playing blues when he was 14, at first with a band of relatives and then with blues-singing pimp Fillmore Slim before becoming a fixture at the Matrix, the city’s preeminent rock club during the psychedelic Summer of Love, backing such visiting artists as Earl Hooker and Magic Sam. Michael Bloomfield became a close friend and mentor. The two musicians lived together for a period, and the famous guitarist even produced a Walker demo for Buddah Records, though nothing came of it. Then, in 1975, Walker walked away from the blues completely in order to escape the fast life and the drugs and alcohol associated with it that he saw negatively affecting Bloomfield and other musician friends. Walker knew nothing about the blues business when he started doing blues gigs again around the Bay Area with a band he’d put together, as a member of Oakland blues singer-guitarist Haskell “Cool Papa” Sadler’s band, and (for a tour of Europe) with the ad hoc Mississippi Delta Blues Band. -

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

P36-37Spe Layout 1

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, JUNE 25, 2014 Gossip Former ‘GMA’ host Lunden has breast cancer ormer “Good Morning America” host Joan Lunden says she has breast chemotherapy. She said after the initial shock of the diagnosis, she cancer. She disclosed her diagnosis on yesterday’s edition of the ABC resolved to learn everything she can about the illness and go into what Fmorning show, which she co-anchored from 1980 through 1997. She she called “warrior mode.” She said she expects to make a full recovery. The spoke with “GMA” host Robin Roberts, who has also been treated for breast 63-year-old Lunden is now a health and wellness advocate. She has writ- cancer recently, as has “GMA” co-host Amy Robach. Lunden said her treat- ten eight books. ment will include surgery and radiation. She said she’s already started Sting: My kids won’t inherit my fortune ith every step they take and every move they make, Sting’s kids will have to make their own Wfinancial way. The singer-songwriter says he does- n’t plan to leave anything for his three daughters and three sons, and that they’re fine with that. “I told them there won’t be much money left because we are spending it! We have a lot of commitments. What comes in, we spend, and there isn’t much left,” he said in an interview with The Daily Mail. “I certainly don’t want to leave them trust funds that are albatrosses round their necks,” added the singer-song- writer, whose semi-autobiographical musical “The Last Ship” premiered last week in Chicago. -

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and Their Use for Composition

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and their Use for Composition submitted by Georg Boenn for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Bath Department of Computer Science February 2011 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author. This thesis may not be consulted, photocopied or lent to other libraries without the permission of the author for 3 years from the date of acceptance of the thesis. Signature of Author . .................................. Georg Boenn To Daiva, the love of my life. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Musical Time and the Problem of Musical Form . 17 1.2 Context of Research and Research Questions . 18 1.3 Previous Publications . 24 1.4 Contributions..................................... 25 1.5 Outline of the Thesis . 27 2 Background and Related Work 28 2.1 Introduction...................................... 28 2.2 Representations of Musical Rhythm . 29 2.2.1 Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 29 2.2.2 The Piano-Roll Notation . 33 2.2.3 Necklace Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 34 2.2.4 Adjacent Interval Spectrum . 36 2.3 Onset Detection . 36 2.3.1 ManualTapping ............................... 36 The times Opcode in Csound . 38 2.3.2 MIDI ..................................... 38 MIDIFiles .................................. 38 MIDIinReal-Time.............................. 40 2.3.3 Onset Data extracted from Audio Signals . 40 2.3.4 Is it sufficient just to know about the onset times? . 41 2.4 Temporal Perception . -

The History of Rock, a Monthly Magazine That Reaps the Benefits of Their Extraordinary Journalism for the Reader Decades Later, One Year at a Time

L 1 A MONTHLY TRIP THROUGH MUSIC'S GOLDEN YEARS THIS ISSUE:1969 STARRING... THE ROLLING STONES "It's going to blow your mind!" CROSBY, STILLS & NASH SIMON & GARFUNKEL THE BEATLES LED ZEPPELIN FRANK ZAPPA DAVID BOWIE THE WHO BOB DYLAN eo.ft - ink L, PLUS! LEE PERRY I B H CREE CE BEEFHE RT+NINA SIMONE 1969 No H NgWOMI WI PIK IM Melody Maker S BLAST ..'.7...,=1SUPUNIAN ION JONES ;. , ter_ Bard PUN FIRS1tintFaBil FROM 111111 TY SNOW Welcome to i AWORD MUCH in use this year is "heavy". It might apply to the weight of your take on the blues, as with Fleetwood Mac or Led Zeppelin. It might mean the originality of Jethro Tull or King Crimson. It might equally apply to an individual- to Eric Clapton, for example, The Beatles are the saints of the 1960s, and George Harrison an especially "heavy person". This year, heavy people flock together. Clapton and Steve Winwood join up in Blind Faith. Steve Marriott and Pete Frampton meet in Humble Pie. Crosby, Stills and Nash admit a new member, Neil Young. Supergroups, or more informal supersessions, serve as musical summit meetings for those who are reluctant to have theirwork tied down by the now antiquated notion of the "group". Trouble of one kind or another this year awaits the leading examples of this classic formation. Our cover stars The Rolling Stones this year part company with founder member Brian Jones. The Beatles, too, are changing - how, John Lennon wonders, can the group hope to contain three contributing writers? The Beatles diversification has become problematic. -

History As an Anecdote

eric B shumwayShlimway in the first place thejournalthebhe journal is a product of a literary adolescent mormon pacific historical society conference talk saturday april 10 1982 who wrote most of it after he had been totally immersed in the tongan culture thinking and speaking only tongan for over two years the document is full HISTORY AS AN ANECDOTE of secondsecondlanguagelanguage interference what offends is more a lack of rhetorical my purpose today is toco discuss some experiences and events during aymy restraint than of truthful intent there is the twisted grammar the bloated mission in tonga 195919621959 1962 which from the perspective now of two decades style in which every noun is accompanied by a heavy adjective the unidimen- constituted certain rights of passage in my growth as a human being and a sional point of view in which the missionary seems to be the chief figure latterlatterdayday saint my material is taken largely from my missimissionaryonaryconary journal1 in a drama whose other characters stand vaguely in the wings coming to life typically what happened to me in tonga by way of an elevation of consciousness only when his oversized shadow passes over them there is too much interpreting and spiritual maturity is duplicated repeatedly in every mission of the church and not enough telling the irritating author intrusion on the subject the but perhaps there are some insights and aberrations which may interest a victimizing of true poignancy by overwrought description overlooking these church history in the pacific buff -

Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia

Title Artist Label Tchaikovsky: Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 6689 Prokofiev: Two Sonatas for Violin and Piano Wilkomirska and Schein Connoiseur CS 2016 Acadie and Flood by Oliver and Allbritton Monroe Symphony/Worthington United Sound 6290 Everything You Always Wanted to Hear on the Moog Kazdin and Shepard Columbia M 30383 Avant Garde Piano various Candide CE 31015 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 352 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 353 Claude Debussy Melodies Gerard Souzay/Dalton Baldwin EMI C 065 12049 Honegger: Le Roi David (2 records) various Vanguard VSD 2117/18 Beginnings: A Praise Concert by Buryl Red & Ragan Courtney various Triangle TR 107 Ravel: Quartet in F Major/ Debussy: Quartet in G minor Budapest String Quartet Columbia MS 6015 Jazz Guitar Bach Andre Benichou Nonsuch H 71069 Mozart: Four Sonatas for Piano and Violin George Szell/Rafael Druian Columbia MS 7064 MOZART: Symphony #34 / SCHUBERT: Symphony #3 Berlin Philharmonic/Markevitch Dacca DL 9810 Mozart's Greatest Hits various Columbia MS 7507 Mozart: The 2 Cassations Collegium Musicum, Zurich Turnabout TV-S 34373 Mozart: The Four Horn Concertos Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Mason Jones Columbia MS 6785 Footlifters - A Century of American Marches Gunther Schuller Columbia M 33513 William Schuman Symphony No. 3 / Symphony for Strings New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 7442 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Westminster Choir/various artists Columbia ML 5200 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 (Pathetique) Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Columbia ML 4544 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 Cleveland Orchestra/Rodzinski Columbia ML 4052 Haydn: Symphony No 104 / Mendelssohn: Symphony No 4 New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia ML 5349 Porgy and Bess Symphonic Picture / Spirituals Minneapolis Symphony/Dorati Mercury MG 50016 Beethoven: Symphony No 4 and Symphony No. -

Transcription of LGBT Oral History 060: Colin Kreitzer

LGBT History Project of the LGBT Center of Central PA Located at Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections http://archives.dickinson.edu/ Documents Online Title: LGBT Oral History: Colin Kreitzer Date: February 16, 2017 Location: LGBT Oral History – Kreitzer, Colin – 060 Contact: LGBT History Project Archives & Special Collections Waidner-Spahr Library Dickinson College P.O. Box 1773 Carlisle, PA 17013 717-245-1399 [email protected] Interviewee: Colin Kreitzer Interviewer: Barry Loveland Videographer: Catherine McCormick Date: Thursday, February 16, 2017 Place: Colin’s home in Harrisburg Transcriber: Amanda Donoghue Proofreader: VJ Kopacki Finalized by Mary Libertin (July 2020) Abstract: Colin Kreitzer was born in 1947 in Enola, Pennsylvania, and grew up in Wormleysburg, Pennsylvania with his parents and his younger sister. He attended West Chester College and moved to Harrisburg in 1977, where he began getting involved in the gay community through activism and social activities. In this interview Colin reviews his involvement in the Gay and Lesbian Switchboard of Harrisburg, Dignity, Metropolitan Community Church, and volleyball. He also talks about the stigma of growing up as a closeted gay man, the bullying he experienced in primary and secondary school, and how he came to accept his sexuality and come out when he was in college. He discusses his past relationships and the struggles that he has experienced trying to forge healthy, emotional connections with others. Colin is also involved in Alcoholics Anonymous, he and explains the values he has gained from the organization and the changes in his own character and behavior. CM: So we are recording. BL: Okay, my name’s Barry Loveland, and I’m here with Catherine McCormick who’s our videographer, and we’re here on behalf of the LGBT Center of Central Pennsylvania History Project. -

The Haec Dies Gradual the Formulas and the Structure Pitches

68 The Haec dies Gradual The formulas and the structure pitches The primary structure pitches for recitation and accentuation are A (the Final of the mode) and C (the Dominant and a universal structure pitch). Punctuation occurs: 1) on A (the Final); 2) on C (the Dominant and universal structure pitch); 3) on F (the other universal structure pitch) and 4) on D (as a suspended cadence on the fourth above the Final). The first phrase (unique to this gradual): The structure pitches: -cc6côccc8cccc8ccccccccccc6ccccc Haec di- es, The initial structure pitch A is given a great deal of emphasis, both by the large Uncinus in Laon 239 and by the t (tenete = lengthen, hold) in the Cantatorium of St. Gall. It is followed by a rapidly moving ornament that circles the A much like the motion of a softball pitcher, in order to add momentum and intensity to the final A before ascending to C. The ornament ends with an Oriscus on the final A that builds the intensity even further until it reaches the C, the 69 climax of the entire melodic line over the word Haec. The tension continues over the accented syllable of the word di-es by means of the rapid, triple pulsation of the C, the Dominant of the piece. The melody then descends to A (the Final of the piece) and becomes a rapid alternation between A and G that swings forcefully to the last A on that syllable. The A is repeated for the final syllable of the word to produce a simple redundant cadence. -

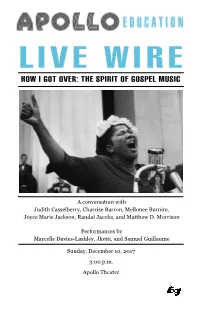

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

JUST ONE LOOK-Doris Troy/Gregory Carroll 4/4 1...2...1234

JUST ONE LOOK-Doris Troy/Gregory Carroll 4/4 1...2...1234 Intro: | | | | | Just one look and I fell so hard, in love with you, oh-oh, oh-oh. I found out, how good it feels, to have your love, oh-oh, oh-oh. Say you will, will be mine, for-ever and al-ways, oh-oh, oh-oh. Just one look, and I knew, that you were my only one, oh oh-oh oh. I thought I was dreamin', but I was wrong, yeah, yeah, yeah. Oh, but-a, I'm gonna keep on schemin', till I can make you, make you my own. So you see, I really care, with-out you I'm nothin', oh-oh, oh-oh. Just one look and I know, I'll get you some-day, oh-oh, oh-oh. Just one look, that's all it took, just one look, that's all it took. Just one look, that's all it took for me! JUST ONE LOOK-Doris Troy/Gregory Carroll 4/4 1...2...1234 Intro: | A | D | A | E7 | A F#m D E7 Just one look and I fell so hard, in love with you, oh-oh, oh-oh. A F#m D E7 I found out, how good it feels, to have your love, oh-oh, oh-oh. A F#m D E7 Say you will, will be mine, for-ever and al-ways, oh-oh, oh-oh. A F#m D E7 A A7 Just one look, and I knew, that you were my only one, oh oh-oh oh. -

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies

MULTIDISCIPLINARY ASSOCIATION FOR PSYCHEDELIC STUDIES VOLUME X NUMBER 3 PSYCHEDELICS & CREATIVITY 2 m a p s • v o l u m e X n u m b e r 3 • c r e a t i v i t y 2 0 0 0 Creativity 2000 MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for 1 Introductions Psychedelic Studies) is a membership-based Rick Doblin, Ph.D., Jon Hanna and Sylvia Thyssen organization working to assist psychedelic 4 Psychedelics and the Creation of Virtual Reality researchers around the world design, obtain Excerpted from an interview with Mark Pesce governmental approval, fund, conduct and report on psychedelic research in humans. 6 Visionary Community at Burning Man Founded in 1986, MAPS is an IRS approved By Abrupt 501 (c)(3) non-profit corporation funded 9 The Creative Process and Entheogens by tax-deductible donations. MAPS has Adapted from The Mission of Art previously funded basic scientific research By Alex Grey into the safety of MDMA (3,4-methylene- 12 Left Hand, Wide Eye dioxymethamphetamine, Ecstasy) and has By Connor Freff Cochran opened a Drug Master File for MDMA at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. MAPS is 17 Huxley on Drugs and Creativity Excerpted from a 1960 interview for The Paris Review now focused primarily on assisting scientists to conduct human studies to generate 18 Ayahuasca and Creativity essential information about the risks and By Benny Shanon, Ph.D. psychotherapeutic benefits of MDMA, other 20 MAPS Members Share Their Experiences psychedelics, and marijuana, with the goal Anecdotes by Abram Hoffer, M.D., Ph.D., FRCP(C), of eventually gaining government Dean Chamberlain, Dan Merkur, Ph.D., Sam Patterson, approval for their medical uses.