OF CROSSINGS and CROWDS: RE/SOUNDING SUBJECT FORMATIONS by Devon R. Kehler a Dissertation Submitted T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + Special Guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, During Miami Art Week in December

PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + Special Guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, during Miami Art Week in December Special one-night-only performance to take place on PAMM’s Terrace Thursday, December 1, 2016 MIAMI – November 9, 2016 – Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) announces PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + special guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, performance in celebration of Miami Art Week this December. Taking over PAMM’s terrace overlooking Biscayne Bay, Norwegian Musician and DJ Cashmere Cat will headline a one-night-only performance, kicking off Art Basel in Miami Beach. The show will also feature projected visual elements, set against the backdrop of the museum’s Herzog & de Meuron-designed building. The evening will continue with sets by Trinidadian DJ and music producer Jillionaire, with a special guest performance by Miami-based Luther “Uncle Luke” Campbell, an icon of Hip Hop who has enjoyed worldwide success while still being true to his Miami roots PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + special guest Uncle Luke, takes place on Thursday, December 1, 9pm–midnight, during the museum’s signature Miami Art Week/Art Basel Miami Beach celebration. The event is open to exclusively to PAMM Sustaining and above level members as well as Art Basel Miami Beach, Design Miami/ and Art Miami VIP cardholders. For more information, or to join PAMM as a Sustaining or above level member, visit pamm.org/support or contact 305 375 1709. Cashmere Cat (b. 1987, Norway) is a musical producer and DJ who has risen to fame with 30+ international headline dates including a packed out SXSW, MMW & Music Hall of Williamsburg, and recent single ‘With Me’, which premiered with Zane Lowe on BBC Radio One & video premiere at Rolling Stone. -

Sia THIS IS ACTING ALBUM PRESS RELEASE November 5, 2015

SIA TO RELEASE NEW ALBUM THIS IS ACTING ON JANUARY 29, 2016 SIA PREMIERES VIDEO TODAY FOR “ALIVE” ON VEVO CLICK HERE TO WATCH “ALIVE” FANS WHO PRE-ORDER THIS IS ACTING RECEIVE “ALIVE” AND NEW SONG “BIRD SET FREE” TODAY CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO “BIRD SET FREE” SIA TO PERFORM ON “SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE” THIS SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 7TH ! (New York-November 5, 2015) Singer/songwriter/producer/massive hitmaker Sia today announces that her album THIS IS ACTING will be released everywhere on January 29, 2016 (Monkey Puzzle Records/RCA Records). Sia revealed cover art and album release date for THIS IS ACTING via her new Instagram account earlier this week. In celebration of her album pre-order going live, Sia premieres her video for “Alive” on Vevo. Fans who pre-order THIS IS ACTING will receive “Alive” and new track “Bird Set Free” instantly. Click here to watch the video for “Alive.” Click here to listen to “Bird Set Free.” Sia will be performing “Alive” and “Bird Set Free” on “Saturday Night Live” on November 7th. The video for “Alive” stars 9 year old child actress/dancer Mahiro Takano and was filmed in Chiba, Japan. The video was directed by Sia and Daniel Askill, the same creative team behind the videos for “Chandelier,” “Elastic Heart” and “Big Girls Cry.” In addition to Jessie Shatkin who produced “Alive,” Sia also worked with longtime collaborator/producer Greg Kurstin on THIS IS ACTING. “Alive,” the album’s first single was written by Sia, Adele and Tobias Jesso, Jr. and was produced by Jesse Shatkin, who also co-wrote and co-produced Sia’s massive four-time Grammy nominated “Chandelier.” Sia released her #1 charting, critically-acclaimed, and gold-certified album 1000 FORMS OF FEAR (Monkey Puzzle Records/RCA Records) last year in July, which features her massive breakthrough singles “Chandelier” and “Elastic Heart.” The groundbreaking video for “Chandelier” has enjoyed an unprecedented 965 million views and its follow-up video “Elastic Heart” with over 436 million views. -

Transcription of LGBT Oral History 060: Colin Kreitzer

LGBT History Project of the LGBT Center of Central PA Located at Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections http://archives.dickinson.edu/ Documents Online Title: LGBT Oral History: Colin Kreitzer Date: February 16, 2017 Location: LGBT Oral History – Kreitzer, Colin – 060 Contact: LGBT History Project Archives & Special Collections Waidner-Spahr Library Dickinson College P.O. Box 1773 Carlisle, PA 17013 717-245-1399 [email protected] Interviewee: Colin Kreitzer Interviewer: Barry Loveland Videographer: Catherine McCormick Date: Thursday, February 16, 2017 Place: Colin’s home in Harrisburg Transcriber: Amanda Donoghue Proofreader: VJ Kopacki Finalized by Mary Libertin (July 2020) Abstract: Colin Kreitzer was born in 1947 in Enola, Pennsylvania, and grew up in Wormleysburg, Pennsylvania with his parents and his younger sister. He attended West Chester College and moved to Harrisburg in 1977, where he began getting involved in the gay community through activism and social activities. In this interview Colin reviews his involvement in the Gay and Lesbian Switchboard of Harrisburg, Dignity, Metropolitan Community Church, and volleyball. He also talks about the stigma of growing up as a closeted gay man, the bullying he experienced in primary and secondary school, and how he came to accept his sexuality and come out when he was in college. He discusses his past relationships and the struggles that he has experienced trying to forge healthy, emotional connections with others. Colin is also involved in Alcoholics Anonymous, he and explains the values he has gained from the organization and the changes in his own character and behavior. CM: So we are recording. BL: Okay, my name’s Barry Loveland, and I’m here with Catherine McCormick who’s our videographer, and we’re here on behalf of the LGBT Center of Central Pennsylvania History Project. -

ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2016 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2016 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 RIPCORD Keith Urban <P> CAP/EMI 4744465 2 FRIENDS FOR CHRISTMAS John Farnham & Olivia Newton John <P> SME 88985387172 3 THE SECRET DAUGHTER (SONGS FROM THE TV SERIES) Jessica Mauboy <P> SME 88985339142 4 DRINKING FROM THE SUN, WALKING UNDER STARS REST… Hilltop Hoods <G> GE/UMA GER021 5 SKIN Flume <G> FCL/EMI FCL160CD 6 THIS IS ACTING Sia <G> INE IR5241CD 7 BLOOM Rüfüs <G> SIO/SME SWEATA009 8 GIMME SOME LOVIN': JUKEBOX VOL. II Human Nature <G> SME 88985338142 9 WINGS OF THE WILD Delta Goodrem <G> SME 88985352572 10 CLASSIC CARPENTERS Dami Im SME 88875150102 11 TELLURIC Matt Corby MER/UMA 4770068 12 WILDFLOWER The Avalanches MOD/EMI 4790024 13 THIS COULD BE HEARTBREAK The Amity Affliction RR/WAR 1686174782 14 THE VERY BEST INXS <P>6 PET/UMA 5335934 15 WACO Violent Soho IOU/UMA IOU143 16 THE VERY VERY BEST OF CROWDED HOUSE Crowded House <P>2 CAP/EMI 9174032 17 SOUL SEARCHIN' Jimmy Barnes LIB/UMA LMCD0295 18 BLUE NEIGHBOURHOOD Troye Sivan <G> EMI 4760061 19 SKELETON TREE Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds KOB/INE BS009CD 20 THE BEST OF The Wiggles ABC/UMA 4794051 21 CURRENTS Tame Impala <G> MOD/UMA 4730676 22 DREAM YOUR LIFE AWAY Vance Joy <P> LIB/UMA LMCD0247 23 CIVIL DUSK Bernard Fanning DEW/UMA DEW9000850 24 50 BEST SONGS Play School ABC/UMA 4792056 25 THE BEST OF COLD CHISEL - ALL FOR YOU Cold Chisel <P>2 CC/UMA CCC002 26 TOGETHER Marina Prior & Mark Vincent SME -

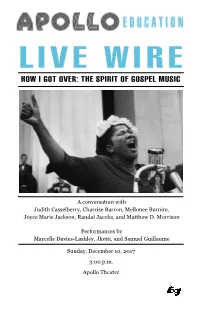

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

Scholastic Course Evaluation Booklet ^^^''^^^'^'^^^'^^'^^^'^^^ Xwsmdusl Rirrinrstrotrotbtrrjnnnnnn

scholastic course evaluation booklet ^^^''^^^'^'^^^'^^'^^^'^^^ xwSMDUSl rirrinrsTroTroTBTrrjnnnnnn ^< ^^C^^:"** A Gilbert Friehdmaker . Famous name ALL-WEATHER GOATS at savings of 1/4 1/3 You'll i-ecognize ihe name of this famous make, the labels arc in the coats . you'll also recog nize these coats as being outstanding values. In a variety of lined and unlined styles, in the most-wanted colors. Regularly priced from .$42.50 to $65. now reduced as much as one-half to win new friends and keep old ones. BUY NOW ... PAY NEXT SUMMER WHEN IT'S MORE CONVENIENT Pay one third in June/one-third in July/one-third in August we never add a service or canying charge OPEN MONDAY THROUGH SATURDAY 9 TILL 6 trQ.9.9.g.g.0-gJI P 0 9 Q P.0.P.9.Q.9,QJ>. GILBERT'S 1.9.9 9.9.9.9.9_9 9 9.9.9.9,9.9_ttJULRJLg lampu$j ON THE CAMPUS... NOTRE DAME Juggler Subscription: 3 issues only $2.00 mailed off campus and out of town Third Issue Soon! delivered on campus. The Poetry of Make check payable to: Juggler Rob Barteletti Box 583 Steve Brion Notre Dame, Ind. Pat Moran Vincent B. Sherry Name "Without usura"—E.P. Address '• General Program / Jack Fiala, chairman Lee Aires, Tom Booker, Jim Bryan, Ray Condon, Barney Gallagher, Phil Glotzbach, Ken Guentert, Paul Hraber, Norm Lerum, Mark Mahoney. St. Mary's Government / Robert Bratke, chairman Course Evaluation Perry Aberli, Claude Chenard, Jim Foster, Dave Gomez, Richard Hunter, Richard Kappler, Marilyn Murphy, Jack Nagle, Ray Offenheiser, Frank Palopoli, Ron Pearson, John Riordan, Dick Terier, Mark Walbran, Robert Webb, Maureen Meter / general chairman Tim Westman, Chris Wolfe, John Zimmerman. -

The Case of Rihanna: Erotic Violence and Black Female Desire

Fleetwood_Fleetwood 8/15/2013 10:52 PM Page 419 Nicole R. Fleetwood The Case of Rihanna: Erotic Violence and Black Female Desire Note: This article was drafted prior to Rihanna and Chris Brown’s public reconciliation, though their rekindled romance supports many of the arguments outlined herein. Fig. 1: Cover of Esquire, November 2011 issue, U. S. Edition. Photograph by Russell James. he November 2011 issue of Esquire magazine declares Rihanna “the sexiest Twoman alive.” On the cover, Rihanna poses nude with one leg propped, blocking view of her breast and crotch. The entertainer stares out provocatively, with mouth slightly ajar. Seaweed clings to her glistening body. A small gun tattooed under her right arm directs attention to her partially revealed breast. Rihanna’s hands brace her body, and her nails dig into her skin. The feature article and accompanying photographs detail the hyperbolic hotness of the celebrity; Ross McCammon, the article’s author, acknowledges that the pop star’s presence renders him speechless and unable to keep his composure. Interwoven into anecdotes and narrative scenes explicating Rihanna’s desirability as a sexual subject are her statements of her sexual appetite and the pleasure that she finds in particular forms of sexual play that rehearse gendered power inequity and the titillation of pain. That Rihanna’s right arm is carefully positioned both to show the tattoo of the gun aimed at her breast, and that her fingers claw into her flesh, commingle sexual pleasure and pain, erotic desire and violence. Here and elsewhere, Rihanna employs her body as a stage for the exploration of modes of violence structured into hetero- sexual desire and practices. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went. -

Vanessa Parish Episode Transcription.Docx

EPISODE 34- Vanessa Parish [INTRODUCTION] [00:00:04] TR: Welcome back to the Afros and Knives Podcast, the interview series featuring black women working in food and beverage, wine, hospitality, food tech, food science, agriculture, food justice and food media. I am your host, Tiffani Rozier. This week’s guest is pastry chef, food writer and creator of the Pinch of Brown Sugar brand, Vanessa Parish. Vanessa’s work as a pastry chef and mental health advocate is shaped by her identity as a queer, black, indigenous woman moving through the world. She is an active board member of the Queer Food Foundation, whose mandate is to promote, protect, fund and create queer food spaces, and also to recognize honor and celebrate queer food workers and chefs. She is just launching a candle line called Vanessa Parrish Sweet Comfort. It is a collection of candles, inspired by some of your favorite desserts, like the sage and vanilla, which reminds you of an ice cream; let's see, apples and maple bourbon with caramelized pralines, then brown sugar, fig and cardamom. Be sure to visit the vanessaparish.com, in order to grab your candles. They do sell out. They do, they don’t end up out of stock, so you definitely want to get your hands on those. You can catch some of Vanessa’s work on Blavity, BET, Tasty. You can follow her work and her story on Instagram @PinchOfBrownSugar, as well as you can hunt the internet and find her on YouTube, Amazon Prime, Apple TV. She is everywhere.