Aw Ae Oo—Scots in Scotland and Ulster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Norse Element in the Orkney Dialect Donna Heddle

The Norse element in the Orkney dialect Donna Heddle 1. Introduction The Orkney and Shetland Islands, along with Caithness on the Scottish mainland, are identified primarily in terms of their Norse cultural heritage. Linguistically, in particular, such a focus is an imperative for maintaining cultural identity in the Northern Isles. This paper will focus on placing the rise and fall of Orkney Norn in its geographical, social, and historical context and will attempt to examine the remnants of the Norn substrate in the modern dialect. Cultural affiliation and conflict is what ultimately drives most issues of identity politics in the modern world. Nowhere are these issues more overtly stated than in language politics. We cannot study language in isolation; we must look at context and acculturation. An interdisciplinary study of language in context is fundamental to the understanding of cultural identity. This politicising of language involves issues of cultural inheritance: acculturation is therefore central to our understanding of identity, its internal diversity, and the porousness or otherwise of a language or language variant‘s cultural borders with its linguistic neighbours. Although elements within Lowland Scotland postulated a Germanic origin myth for itself in the nineteenth century, Highlands and Islands Scottish cultural identity has traditionally allied itself to the Celtic origin myth. This is diametrically opposed to the cultural heritage of Scotland‘s most northerly island communities. 2. History For almost a thousand years the language of the Orkney Islands was a variant of Norse known as Norroena or Norn. The distinctive and culturally unique qualities of the Orkney dialect spoken in the islands today derive from this West Norse based sister language of Faroese, which Hansen, Jacobsen and Weyhe note also developed from Norse brought in by settlers in the ninth century and from early Icelandic (2003: 157). -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Migrating Minds

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 5: Issue 1 Migrating Minds AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 5, Issue 1 Autumn 2011 Migrating Minds Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative ISSN 1753-2396 Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies General Editor: Cairns Craig Issue Editor: Paul Shanks Associate Editor: Michael Brown Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin Graham Walker, Queen’s University, Belfast International Advisory Board: Don Akenson, Queen’s University, Kingston Tom Brooking, University of Otago Keith Dixon, Université Lumière Lyon 2 Marjorie Howes, Boston College H. Gustav Klaus, University of Rostock Peter Kuch, University of Otago Graeme Morton, University of Guelph Brad Patterson, Victoria University, Wellington Matthew Wickman, Brigham Young David Wilson, University of Toronto The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal published twice yearly in autumn and spring by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Norn Elements in the Shetland Dialect

Hugvísindadeild Norn elements in the Shetland dialect A Historical and Linguistic Review B.A. Essay Auður Dagný Jónsdóttir September, 2013 University of Iceland Faculty of Humanities Department of English Norn elements in the Shetland dialect A Historical and Linguistic Review B.A. Essay Auður Dagný Jónsdóttir Kt.: 270172-5129 Supervisors: Þórhallur Eyþórsson and Pétur Knútsson September, 2013 2 Abstract The languages spoken in Shetland for the last twelve hundred years have ranged from Pictish, Norn to Shetland Scots. The Norn language started to form after the settlements of the Norwegian Vikings in Shetland. When the islands came under the British Crown, Norn was no longer the official language and slowly declined. One of the main reasons the Norn vernacular lived as long as it did, must have been the distance from the mainland of Scotland. Norn was last heard as a mother tongue in the 19th century even though it generally ceased to be spoken in people’s daily life in the 18th century. Some of the elements of Norn, mainly lexis, have been preserved in the Shetland dialect today. Phonetic feature have also been preserved, for example is the consonant’s duration in the Shetland dialect closer to the Norwegian language compared to Scottish Standard English. Recent researches indicate that there is dialectal loss among young adults in Lerwick, where fifty percent of them use only part of the Shetland dialect while the rest speaks Scottish Standard English. 3 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. The origin of Norn ................................................................................................................. 6 3. The heyday of Norn ............................................................................................................... 7 4. King James III and the Reformation .................................................................................. -

Letter from the President the Scotch-Irish Society of the United

OCIETY S O H F S I T R H I - E H NEWSLETTER Spring 2012 U C . T S O . A C . S The Scotch-Irish Society 1889 of the United States of America Letter from the President You would think that a celebration of our Scotch-Irish culture would be seen by all as a positive expression of a great American heritage, but not everyone speaks kindly of us. Kevin Myers, the renowned Irish columnist recently wrote “There's no end to this nonsense of subdividing society, defining The Hermitage – Nashville, Tennessee and redefining ‘identity’, or even worse, ‘culture’, like a coke-dealer fine-cutting a stash on a mirror. The outcome is a multiply-divided It has been a few years since I visited community, sects in the city, with almost everyone having their own The Hermitage , home of another mini-culture. Healthy societies don't dwell on identity.” Although Scotch-Irish “Jackson,” President Andrew specifically referring to Ulster-Scots and a new BBC documentary Jackson. (Last issue we highlighted the about their unique cuisine, his diatribe could just as easily be home of Stonewall Jackson in Lexington, applied to us. Comments from readers on the newspaper’s website Virginia.) I remember it being an easy day trip, just five miles from the Gaylord were virtually unanimous in taking Mr. Myers to task. Opryland Resort and Convention Center In 2010, Harvard Law professor Noah Feldman wrote of our where I was staying on business and only demise. "So, when discussing the white elite that exercised such twenty minutes from downtown Nashville. -

Imagining Scotland

Imagining Scotland National Self-Depiction in Sir Walter Scott's Waverley , Lewis Grassic Gibbon's Sunset Song , Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting and Alasdair Gray's Lanark Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV (Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften) der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Christian Kucznierz Mühlfeldstr. 12 93083 Obertraubling 2008 Regensburg 2009 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rainer Emig Zweitgutachter: PD Dr. Anne-Julia Zwierlein Acknowledgements In the six years it took to finish this study, I was working simultaneously on my professional career outside of the university. It was Prof. Dr. Rainer Emig's constant encouragement which helped me not to lose sight of the aim I was pursuing in all those years. I would like to thank him for giving me the chance to start my dissertation, for his support, his valuable advice and the fact that I could call on him at any time. Furthermore, I would like to thank PD Dr. Anne-Julia Zwierlein, who on rather short notice agreed to supervise my work, and whose ideas helped to give my thesis the necessary final touches. I would also like to thank my wife, Sandra, and my family, who have been patient enough to understand that my weekends, holidays and evenings after work were mostly busy – and that my mind much too often strayed from important issues. Without their support and understanding, this thesis would never have come into existence. Obertraubling, 2009 Table of Contents page 1. How does Scotland imagine itself? 5 2. Imagi-Nation: Literature and Self-Depiction 8 2.1. The Printed Word, Community and Identity 9 2.2. -

AJ Aitken a History of Scots

A. J. Aitken A history of Scots (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee Editor’s Introduction In his ‘Sources of the vocabulary of Older Scots’ (1954: n. 7; 2015), AJA had remarked on the distribution of Scandinavian loanwords in Scots, and deduced from this that the language had been influenced by population movements from the North of England. In his ‘History of Scots’ for the introduction to The Concise Scots Dictionary, he follows the historian Geoffrey Barrow (1980) in seeing Scots as descended primarily from the Anglo-Danish of the North of England, with only a marginal role for the Old English introduced earlier into the South-East of Scotland. AJA concludes with some suggestions for further reading: this section has been omitted, as it is now, naturally, out of date. For a much fuller and more detailed history up to 1700, incorporating much of AJA’s own work on the Older Scots period, the reader is referred to Macafee and †Aitken (2002). Two textual anthologies also offer historical treatments of the language: Görlach (2002) and, for Older Scots, Smith (2012). Corbett et al. eds. (2003) gives an accessible overview of the language, and a more detailed linguistic treatment can be found in Jones ed. (1997). How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘A history of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/A_history_of_Scots_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published in the Introduction, The Concise Scots Dictionary, ed.-in-chief Mairi Robinson (Aberdeen University Press, 1985, now published Edinburgh University Press), ix-xvi. -

THE SCOTS LANGUAGE in DRAMA by David Purves

THE SCOTS LANGUAGE IN DRAMA by David Purves THE SCOTS LANGUAGE IN DRAMA by David Purves INTRODUCTION The Scots language is a valuable, though neglected, dramatic resource which is an important part of the national heritage. In any country which aspires to nationhood, the function of the theatre is to extend awareness at a universal level in the context of the native cultural heritage. A view of human relations has to be presented from the country’s own national perspective. In Scotland prior to the union of the Crowns in 1603, plays were certainly written with this end in view. For a period of nearly 400 years, the Scots have not been sure whether to regard themselves as a nation or not, and a bizarre impression is now sometimes given of a greater Government commitment to the cultures of other countries, than to Scotland’s indigenous culture. This attitude is reminiscent of the dismal cargo culture mentality now established in some remote islands in the Pacific, which is associated with the notion that anything deposited on the beach is good, as long as it comes from elsewhere. This paper is concerned with the use in drama of Scots as a language in its own right:, as an internally consistent register distinct from English, in which traditional linguistic features have not been ignored by the playwright. Whether the presence of a Scottish Parliament in the new millennium will rid us of this provincial mentality remains to be seen. However, it will restore to Scotland a national political voice, which will allow the problems discussed in this paper to be addressed. -

Dialects in Contact Language, Resulting for New Towns and at Transplanted Varieties of Research Into Example from Urbanization and Colonization

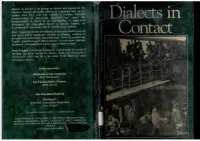

1 observe and account for (he Directs in Contact is an aliempt to a language have on one influence mutually intelligible dialects Of examines UngttistM another when they come into contact, h and argues th.it accommodation in faee-to-face interaction Dialects in of longer-term accommodation is crucial to an understanding features, the phenomena: the geographical spread of linguistic development of 'interdialect* and the growth of new dialects. border areas and Peter Trudgill looks at the development of dialects in Contact language, resulting for new towns and at transplanted varieties of research into example from urbanization and colonization. Based on draws important English. Scandinavian and other languages, his book linguistic data. I'll f theoretical conclusions from a wide range of Science at the Universitj of Peter Trudgill is Professor in Linguistic I Geographical Reading. His books include On Dialect: Social and Blackwell series Perspectives (1983) and he is the editor of the Language in Society. In the same series Pidgin and Creole Linguistics Peter Mtihlhausler The Sociolinguistics of Society Ralph Fasold Also from Basil Blackwell On Dialect* Social and Geographical Perspectives Peter Trudgill m is not available in the USA I, ir copyright reasons this edition Alfred Stieglitz. photogravure (artist's Cover illustration: 77k- Steerage, 1907. by collection. The proof) from Camera Work no. 36. 1911. size of print. 7)4 reproduced by k.nd Museum of Modern An. New York, gilt of Alfred Stieglitz. is permission Cover design by Martin Miller LANGUAGE IN SOCIETY Dialects in Contact GENERAL EDITOR: Peter Trudgill, Professor of Linguistic Science, University of Reading PETER TRUDGILL advisory editors: Ralph Fasold, Professor of Linguistics, Georgetown University William Labov, Professor of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania 1 Language and Social Psychology Edited by Howard Giles and Robert N. -

Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected]

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University Theology Faculty Scholarship Theology 5-2000 Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/theologyfaculty Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Beebe, Keith Edward. "Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival." Theology Matters 6.2 (2000): 1-8. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. TTheology MMattersatters A Publication of Presbyterians for Faith, Family and Ministry Vol 6 No 2 • Mar/Apr 2000 Touched By The Fire: Presbyterians and Revival By Keith Edward Beebe St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland, Undoubtedly, the preceding account might come as a Tuesday, March 30, 1596 surprise to many Presbyterians, as would the assertion that As the Holy Spirit pierces their hearts with razor- such experiences were a familiar part of the spiritual sharp conviction, John Davidson concludes his terrain of our early Scottish ancestors. What may now message, steps down from the pulpit, and quietly seem foreign to the sensibilities and experience of present- returns to his seat. With downcast eyes and heaviness day Presbyterians was an integral part of our early of heart, the assembled leaders silently reflect upon spiritual heritage. Our Presbyterian ancestors were no their lives and ministry. The words they have just strangers to spiritual revival, nor to the unusual heard are true and the magnitude of their sin is phenomena that often accompanied it. -

Authentic Language

! " " #$% " $&'( ')*&& + + ,'-* # . / 0 1 *# $& " * # " " " * 2 *3 " 4 *# 4 55 5 * " " * *6 " " 77 .'%%)8'9:&0 * 7 4 "; 7 * *6 *# 2 .* * 0* " *6 1 " " *6 *# " *3 " *# " " *# 2 " " *! "; 4* $&'( <==* "* = >?<"< <<'-:@-$ 6 A9(%9'(@-99-@( 6 A9(%9'(@-99-(- 6A'-&&:9$' ! '&@9' Authentic Language Övdalsk, metapragmatic exchange and the margins of Sweden’s linguistic market David Karlander Centre for Research on Bilingualism Stockholm University Doctoral dissertation, 2017 Centre for Research on Bilingualism Stockholm University Copyright © David Budyński Karlander Printed and bound by Universitetsservice AB, Stockholm Correspondence: SE 106 91 Stockholm www.biling.su.se ISBN 978-91-7649-946-7 ISSN 1400-5921 Acknowledgements It would not have been possible to complete this work without the support and encouragement from a number of people. I owe them all my humble thanks.