Articles Cold Start in Strategic Calculus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute Asian Studies Institute & Centre for Strategic Studies Rajat Ganguly ISSN: 11745991 ISBN: 0475110552

Asian Studies Institute Victoria University of Wellington 610 von Zedlitz Building Kelburn, Wellington 04 463 5098 [email protected] www.vuw.ac.nz/asianstudies India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute Asian Studies Institute & Centre for Strategic Studies Rajat Ganguly ISSN: 11745991 ISBN: 0475110552 Abstract The root cause of instability and hostility in South Asia stems from the unresolved nature of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. It has led to two major wars and several near misses in the past. Since the early 1990s, a 'proxy war' has developed between India and Pakistan over Kashmir. The onset of the proxy war has brought bilateral relations between the two states to its nadir and contributed directly to the overt nuclearisation of South Asia in 1998. It has further undermined the prospects for regional integration and raised fears of a deadly IndoPakistan nuclear exchange in the future. Resolving the Kashmir dispute has thus never acquired more urgency than it has today. This paper analyses the origins of the Kashmir dispute, its influence on IndoPakistan relations, and the prospects for its resolution. Introduction The root cause of instability and hostility in South Asia stems from the unresolved nature of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. In the past fifty years, the two sides have fought three conventional wars (two directly over Kashmir) and came close to war on several occasions. For the past ten years, they have been locked in a 'proxy war' in Kashmir which shows little signs of abatement. It has already claimed over 10,000 lives and perhaps irreparably ruined the 'Paradise on Earth'. -

10 Pakistan's Nuclear Program

10 PAKISTAN’S NUCLEAR PROGRAM Laying the groundwork for impunity C. Christine Fair Contemporary analysts of Pakistan’s nuclear program speciously assert that Pakistan began acquiring a nuclear weapons capability after the 1971 war with India in which Pakistan was vivisected. In this conventional account, India’s 1974 nuclear tests gave Pakistan further impetus for its program.1 In fact, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s first popularly elected prime minister, ini- tiated the program in the late 1960s despite considerable opposition from Pakistan’s first military dictator General Ayub Khan (henceforth Ayub). Bhutto presciently began arguing for a nuclear weapons program as early as 1964 when China detonated its nuclear devices at Lop Nor and secured its position as a permanent nuclear weapons state under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Considering China’s test and its defeat of India in the 1962 Sino–Indian war, Bhutto reasoned that India, too, would want to develop a nuclear weapon. He also knew that Pakistan’s civilian nuclear program was far behind India’s, which predated independence in 1947. Notwithstanding these arguments, Ayub opposed acquiring a nuclear weapon both because he believed it would be an expensive misadventure and because he worried that doing so would strain Pakistan’s western alliances, formalized through the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) and the South-East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Ayub also thought Pakistan would be able to buy a nuclear weapon “off the shelf” from one of its allies if India acquired one first.2 With the army opposition obstructing him, Bhutto was unable to make any significant nuclear headway until 1972, when Pakistan’s army lay in disgrace after losing East Pakistan in its 1971 war with India. -

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, editors Copyright © 2004 The Henry L. Stimson Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Henry L. Stimson Center. Cover design by Design Army. ISBN 0-9747255-8-7 The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street NW Twelfth Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations..................................................................................................... vii Introduction......................................................................................................... ix 1. The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia Michael Krepon ............................................................................................ 1 2. Nuclear Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia: Structural Factors Rodney W. Jones......................................................................................... 25 3. India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture Rajesh M. Basrur ........................................................................................ 56 4. Nuclear Signaling, Missiles, and Escalation Control in South Asia Feroz Hassan Khan ................................................................................... -

India-Pakistan Conflicts – Brief Timeline

India-Pakistan Conflicts – Brief timeline Added to the above list, are Siachin glacier dispute (1984 beginning – 2003 ceasefire agreement), 2016- 17 Uri, Pathankot terror attacks, Balakot surginal strikes by India Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 The war, also called the First Kashmir War, started in October 1947 when Pakistan feared that the Maharaja of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu would accede to India. Following partition, princely states were left to choose whether to join India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Jammu and Kashmir, the largest of the princely states, had a majority Muslim population and significant fraction of Hindu population, all ruled by the Hindu Maharaja Hari Singh. Tribal Islamic forces with support from the army of Pakistan attacked and occupied parts of the princely state forcing the Maharaja Pragnya IAS Academy +91 9880487071 www.pragnyaias.com Delhi, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Tirupati & Pune +91 9880486671 www.upsccivilservices.com to sign the Instrument of Accession of the princely state to the Dominion of India to receive Indian military aid. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on 22 April 1948. The fronts solidified gradually along what came to be known as the Line of Control. A formal cease-fire was declared at 23:59 on the night of 1 January 1949. India gained control of about two-thirds of the state (Kashmir valley, Jammu and Ladakh) whereas Pakistan gained roughly a third of Kashmir (Azad Kashmir, and Gilgit–Baltistan). The Pakistan controlled areas are collectively referred to as Pakistan administered Kashmir. Pragnya IAS Academy +91 9880487071 www.pragnyaias.com Delhi, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Tirupati & Pune +91 9880486671 www.upsccivilservices.com Indo-Pakistani War of 1965: This war started following Pakistan's Operation Gibraltar, which was designed to infiltrate forces into Jammu and Kashmir to precipitate an insurgency against rule by India. -

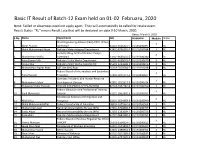

Basic IT Result of Batch 12

Basic IT Result of Batch-12 Exam held on 01-02 Februaru, 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam. Result Status "RL" means Result Late that will be declared on date 9-10 March, 2020. Dated: March 5, 2020 S.No Name Department NIC Studentid Module Status Chief Engineering Adviser (CEA) /CFFC Office, 3 1 Abrar Hussain Islamabad 61101-5666325-7 VU191200097 RL 2 Malik Muhammad Ahsan Pakistan Meteorological Department 42401-8756355-7 VU191200184 3 RL Forestry Wing, M/O of Climate Change, 3 3 Muhammad Shafiq Islamabad 13101-3645024-5 VU191200280 RL 4 Asim Zaman Virk Pakistan Public Works Department 61101-4055043-7 VU191200670 3 RL 5 Rasool Bux Pakistan Public Works Department 45302-1434648-1 VU191200876 3 RL 6 Muhammad Asghar Khan S&T Dte GHQ Rwp 55103-7820568-7 VU191201018 3 RL Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary 3 7 Tariq Hussain Education 37405-0231137-3 VU191200627 RL Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource 3 8 Muhammad Zubair Development Division 42301-0211817-3 VU191200624 RL 9 Khaawaja Shabir Hussain CCD-VIII PAK PWD G-9/1 ISLAMABAD 82103-1652182-9 VU191200700 3 RL Federal Education and Professional Training 3 10 Sajid Mehmood Division 61101-1862402-9 VU191200933 RL Directorate General of Immigration and 3 11 Allah Ditta Passports 61101-6624393-9 VU191200040 RL 12 Malik Muhammad Afzal Federal Directorate of Education 38302-1075962-9 VU191200509 3 RL 13 Muhammad Asad National Accountability Bureau (KPk) 17301-6704686-5 VU191200757 3 RL 14 Sadiq Akbar National Accountability -

Cold Start – Hot Stop? a Strategic Concern for Pakistan

79 COLD START – HOT STOP? A STRATEGIC CONCERN FOR PAKISTAN * Muhammad Ali Baig Abstract The hostile environment in South Asia is a serious concern for the international players. This volatile situation is further fuelled by escalating arms race and aggressive force postures. The Indian Cold Start Doctrine (CSD) has supplemented negatively to the South Asian strategic stability by trying to find a way in fighting a conventional limited war just below the nuclear umbrella. It was reactionary in nature to overcome the shortcomings exhibited during Operation Parakram of 2001-02, executed under the premise of Sundarji Doctrine. The Cold Start is an adapted version of German Blitzkrieg which makes it a dangerous instrument. Apart from many limitations, the doctrine remains relevant to the region, primarily due to the attestation of its presence by the then Indian Army Chief General Bipin Rawat in January 2017. This paper is an effort to probe the different aspects of Cold Start, its prerequisites in provisions of three sets; being a bluff based on deception, myth rooted in misperception, and a reality flanked by escalation; and how and why CSD is a strategic concern for Pakistan. Keywords: Cold Start Doctrine, Strategic Stability, Conventional Warfare, Pakistan, India. Introduction here is a general consensus on the single permanent aspect of international system T that has dominated the international relations ever since and its history and relevance are as old as the existence of man and the civilization itself; the entity is called war.1 This relevance was perhaps best described by Leon Trotsky who averred that “you may not be interested in war, but war may be interested in you.”2 To fight, avert and to pose credible deterrence, armed forces strive for better yet flexible doctrines to support their respective strategies in conducting defensive as well as offensive operations and to dominate in adversarial environments. -

The Indo-Pak Rivalry and the Kashmir Issue: a Historical Analysis in the Security Context of the South Asia

Journal of Political Studies, Vol. 26, Issue - 2, 2019, 73:84 The Indo-Pak Rivalry and the Kashmir Issue: A Historical Analysis in the Security Context of the South Asia Dr. Syed Shahbaz Hussain, Ghulam Mustafa, Muhammad Imran, Adnan Nawaz Abstract The Kashmir issue is a primary source of resentment between India and Pakistan. It is considered the oldest issue on the schedule of the Security Council yet to be resolved. This divisive issue remained unsolved and has become the nuclear flashpoint. The peace of the South Asian region is severely contingent upon the peaceful resolution of the Kashmir dispute. It is not only the pivot of bitterness in the bilateral relation of India and Pakistan, it also a continuous threat to the regional peace in South Asia. This study critically assesses and evaluated the issue in the perspective of historical facts and current context regarding Kashmir. Chronological data presented and describe that the Kashmir issue has deteriorated the fragile security of South Asian region and remained a continuous threat of nuclear escalation in the region. Kashmir issue has severe implications for populace of Kashmir as well as for the region. Keywords: Kashmir Issue, Indo-Pak Rivalry, Security Issues, South Asia, Human Right Violation. Introduction South Asia is considered the most militarized zone of the globe where two nuclear rivals, Pakistan and India, are competing over arm race. The development and economic prosperity of South Asia is traumatized by Indo-Pak rivalry which is deeply rooted in South Asia due to structural asymmetry resulted from faulty distribution of boundaries. Kashmir dispute is the pivotal point of Indo-Pak rivalry which has further aggravated the complex strategic environment of South Asia. -

Year Book 2010–2011

i Year Book 2010 – 2011 Government of Pakistan Finance Division Islamabad www.finance.gov.pk CONTENTS ii S. Subject Page No. No. Preface 1 Mission Statement 2 General 3 Functions of the Finance Division 3 Organizational Chart of the Finance Division 5 A. HRM Wing 6 B. Budget Wing 10 Budget and its Functions 10 Budget Wing’s Profile 11 Performance of Budget Wing 12 Medium Term Budgetary Framework (MTBF) 24 Budget Implementation Unit (BIU) 25 C. Corporate Finance Wing 28 D. Economic Adviser’s Wing 30 E. Expenditure Wing 32 F. External Finance Wing 34 G. External Finance (Policy Wing) 38 H. Economic Reforms Unit (ERU) 47 I. Finance Division (Military) 51 J. Development Wing 54 iii K. Internal Finance Wing 57 State Bank of Pakistan 57 National Bank of Pakistan 57 First Women Bank Limited 58 Pakistan Security Printing Corporation 59 House Building Finance Corporation 60 SME Bank Limited 61 Financial Monitoring Unit (FMU) Karachi 62 Zari Taraqiati Bank Ltd. (ZTBL) 63 L. Investment Wing 65 Competitiveness Support Fund (CFS) 65 National Investment Trust Limited (NITL) 66 Competition Commission of Pakistan(CCP) 72 Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan 86 Joint Investment Companies in Pakistan 103 Infrastructure Project Development Facility (IPDF) 104 M. Provincial Finance 105 O. Regulations Wing 113 P. Auditor General of Pakistan 121 Central Directorate of National Savings(CDNS) 132 Controller General of Accounts (CGA) 136 Pakistan Mint 139 Debt Policy Coordination Office (DPCO) 141 iv COMPILATION TEAM 1. MR. MUHAMMAD ANWAR KHAN Senior Joint Secretary (HRM) 2. MR. MIR AFZAL KHAN Deputy Secretary (Services) 3. -

Governing the Bomb: Civilian Control and Democratic

DCAF GOVERNING THE BOMB Civilian Control and Democratic Accountability of Nuclear Weapons edited by hans born, bates gill and heiner hänggi Governing the Bomb Civilian Control and Democratic Accountability of Nuclear Weapons STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Göran Lennmarker, Chairman (Sweden) Dr Dewi Fortuna Anwar (Indonesia) Dr Alexei G. Arbatov (Russia) Ambassador Lakhdar Brahimi (Algeria) Jayantha Dhanapala (Sri Lanka) Dr Nabil Elaraby (Egypt) Ambassador Wolfgang Ischinger (Germany) Professor Mary Kaldor (United Kingdom) The Director DIRECTOR Dr Bates Gill (United States) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 70 Solna, Sweden Telephone: +46 8 655 97 00 Fax: +46 8 655 97 33 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Governing the Bomb Civilian Control and Democratic Accountability of Nuclear Weapons EDITED BY HANS BORN, BATES GILL AND HEINER HÄNGGI OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2010 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © SIPRI 2010 All rights reserved. -

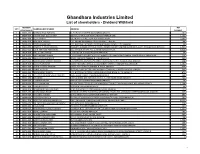

List of Shareholder-Dividend Withheld

Ghandhara Industries Limited List of shareholders - Dividend Withheld MEMBER NET SR # SHAREHOLDER'S NAME ADDRESS FOLIO PAR ID PAYABLE 1 00002-000 MISBAHUDDIN FAROOQI D-151 BLOCK-B NORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI. 461 2 00004-000 FARHAT AFZA BEGUM MST. 166 ABU BAKR BLOCK NEW GARDEN TOWN,LAHORE 1,302 3 00005-000 ALLAH RAKHA 135-MUMTAZ STREETGARHI SHAHOO,LAHORE. 3,293 4 00006-000 AKHTAR A. PERVEZ C/O. AMERICAN EXPRESS CO.87 THE MALL, LAHORE. 180 5 00008-000 DOST MUHAMMAD C/O. NATIONAL MOTORS LIMITEDHUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.KARACHI. 46 6 00010-000 JOSEPH F.P. MASCARENHAS MISQUITA GARDEN CATHOLIC COOP.HOUSING SOCIETY LIMITED BLOCK NO.A-3,OFF: RANDLE ROAD KARACHI. 1,544 7 00013-000 JOHN ANTHONY FERNANDES A-6, ANTHONIAN APT. NO. 1,ADAM ROAD,KARACHI. 5,004 8 00014-000 RIAZ UL HAQ HAMID C-103, BLOCK-XI, FEDERAL.B.AREAKARACHI. 69 9 00015-000 SAIED AHMAD SHAIKH C/O.COMMODORE (RETD) M. RAZI AHMED71/II, KHAYABAN-E-BAHRIA, PHASE-VD.H.A. KARACHI-46. 214 10 00016-000 GHULAM QAMAR KURD 292/8, AZIZABAD FEDERAL B. AREA,KARACHI. 129 11 00017-000 MUHAMMAD QAMAR HUSSAIN C/O.NATIONAL MOTORS LTD.HUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.,P.O.BOX-2706, KARACHI. 218 12 00018-000 AZMAT NAWAZISH AZMAT MOTORS LIMITED, SC-43,CHANDNI CHOWK, STADIUM ROAD,KARACHI. 1,585 13 00021-000 MIRZA HUSSAIN KASHANI HOUSE NO.R-1083/16,FEDERAL B. AREA, KARACHI 434 14 00023-000 RAHAT HUSSAIN PLOT NO.R-483, SECTOR 14-B,SHADMAN TOWN NO.2, NORTH KARACHI,KARACHI. -

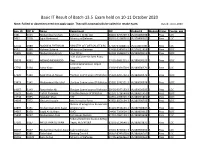

Basic IT Result of Batch-13.5 Exam Held on 10-11 October 2020

Basic IT Result of Batch-13.5 Exam held on 10-11 October 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam. Dated: 10-11-2020 App_ID Off_Sr Name Department NIC Studentid Module Status Course_app 7441 2515 Muhammad Usman Defence / GHQ/ AST 38201-0703749-3 VU170400498 3 Pass LDC 7437 2518 Sajid Mehmood Ministry of Defence 38201-5218076-5 VU170400501 3 Pass LDC 12741 2989 NOSHABA EHTISHAM MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS 37405-0320841-2 VU170403780 3 Pass LDC 4992 1360 Kishwer Sultana Ministry of Defence 37405-5949699-2 VU170911618 3 Pass UDC 15385 4801 Muhammad Akram Post Office 32403-1626012-5 VU180600112 3 Pass UDC FGEI (C/G) Dte Sir Syed Road, 15078 4952 ARSHAD MEHMOOD Rwp 37401-9681211-1 VU180600225 3 Pass UDC Central Ammunition Depot 17756 5134 Azhar Khan Sargodha 13102-0361678-9 VU180600371 3 Pass LDC 17126 5140 Syed Waji-ul-Hassan Election Commission of Pakistan 35202-2205762-1 VU180600376 3 Pass UDC 13823 5142 Muhammad Khurshid Election Commission Of Pakistan 35202-2741551-3 VU180600378 3 Pass UDC 14057 5149 Rana Arslan Ali Election Commission of Pakistan 38403-9977153-3 VU180600385 3 Pass LDC 22523 6566 Farhat Yasmeen Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 61101-1718744-8 VU180601452 3 Pass UDC 21738 7055 Abdullah Khan PAF 14301-1998716-7 VU180601861 3 Pass UDC 24009 7972 Ghulam Hussain Anti Narcotics Force 45302-8650164-3 VU180700703 3 Pass UDC Bureau of emigration & overseas 24899 8151 Muhammad Azim Awan employment 61101-9516133-1 VU180700847 3 Pass LDC 24067 8178 Saqib Ali Siddiqui GHQ -

Infomation for SECP Till Nov 2020.Xlsx

Information required for the SECP notice DTP 1 Lahore List of Certified Directors Session I: Jan 21-22, 2013 - Session II: Mar 25-26, 2013 S.NO Name of Participant Designation Organization Area of Expertise 1 Ali Altaf Saleem Executive Director Shakarganj Mills Ltd Finance 2 Abdul Rafay Siddique, FCA - Abdul Rafay, Chartered Accountants Accounting & Finance 3 Mohammad Saleem, FCA Partner M. Yousuf Adil Saleem & Co. Audit/Finance/Corporate Affairs/Taxation Business Analysis, Internal Control Risks, Risk Mitigation, Strategic Planning, Business 4 Omer Naseer Risk Analyst InfoTech Private Ltd Management Director Finance & CFO's responsibilities,Looking after Operations of the company especially Production, Safety and 5 Javed Iqbal, FCA Ittehad Chemicals Ltd. CFO Environment, CSR Contracts Management/ interpretation/ (Power Purchase Agreement, Implementation Agreement, 6 Zain-Ul-Abidin, FCA Chief Financial Officer Japan Power Generation Ltd. O&M Agreements) 7 Muneeb Ahmed Dar Director/Chairman First Elite Capital Mudaraba Credit/ Risk Management Chief Executive 8 Shafqat Ellahi Shaikh Ellcot Spinning Mills Ltd/Nagina Group Entrepreneur Officer 9 Muhammad Rizwan Akbar, FCA Chief Financial Officer The Lake City Holdings (Pvt) Ltd. Finance, Audit, Tax and Management. 10 Asif Baig Mirza Director Lahore Stock Exchange Ltd. Financial Management and Economic Analysis 11 Sultan Mubashir, FCA Executive Director Ellcot Spinning Mills Ltd/Nagina Group Financial reporting, Treasury, Corporate &Taxation and Organisation Management 12 Bushra Naz Malik, FCA Director Lahore Stock Exchange Ltd. Governance and Risk Management Have over 29 Years of Post Qualification Experience in diversified fields of Finance, Corporate 13 Waqar Ullah, FCA Director Finance Tariq Glass Industries Ltd. Affairs, Taxation and Allied Matters 14 Naseer A.