An Interview with Rosanna Warren - Asymptote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Penn Warren: a Documentary Volume Contents

Dictionary of Literary Biography • Volume Three Hundred Twenty Robert Penn Warren: A Documentary Volume Contents Plan of the Series xxiii Introduction xxv Acknowledgments xxviii Permissions xxx Works by Robert Penn Warren 3 Chronology 8 Launching a Career: 1905-1933 20 Kentucky Beginnings 20 Facsimile: Pages from the Warren family Bible An Old-Time Childhood—from Warren's poem "Old-Time Childhood in Kentucky" The Author and the Ballplayer-from Will Fridy, "The Author and the Ballplayer: An Imprint of Memory in the Writings of Robert Penn Warren" Early Reading-from Ralph Ellison and Eugene Walter, "The Art of Fiction XVIII: Robert Penn Warren" Clarksville High School. '. -. J , 30 Facsimile: Warren's essay on his first day at Clarksville High School Facsimile: First page of "Munk" in The Purple and Gold, February 1921 Facsimile: "Senior Creed" in The Purple and Gold, April 1921 Writing for The Purple and Gold—from Tom Wibking, "Star's Work Seasoned by Country Living" Becoming a Fugitive 38 "Incidental and Essential": Warren's Vanderbilt Experience-from "Robert Penn Warren: A Reminiscence" A First Published Poem-"Prophecy," The Mess Kit (Foodfor Thought) and Warren letter - to Donald M. Kington, 6 March 1975 The Importance of The Fugitive—horn Louise Cowan, The Fugitive Group: A Literary History Brooks and Warren at Vanderbilt-from Cleanth Brooks, "Brooks on Warren" A Fugitive Anthology-Warren letter to Donald Davidson, 19 September 1926 Katherine Anne Porter Remembers Warren—from Joan Givner, Katherine Ann Porter: A Life A Literary Bird Nest—from Brooks, "A Summing Up" The Fugitives as a Group-from Ellison and Walter, "The Art of Fiction XVIII: Robert Penn Warren" Facsimile: Page from a draft of John Brown A Glimpse into the Warren Family 52 Letters from Home: Filial Guilt in Robert Penn Warren-from an essay by William Bedford Clark xiii Contents DLB 320 Warren and Brooks at Oxford-from Brooks, "Brooks on Warren" Facsimile: Warren postcard to his mother, April 1929 A First Book -. -

Literary Matters a the NEWSLETTER of the ASSOCIATION of LITERARY SCHOLARS, CRITICS, and WRITERS Aut Nuntiare Aut Delectare

Literary Matters a THE NEWSLETTER OF THE ASSOCIATION OF LITERARY SCHOLARS, CRITICS, AND WRITERS Aut nuntiare aut delectare A Year in Presidential Publications: Books by ALSCW Presidents - Past, Present, and Future From The Editor Welcome to the fall issue of Literary Matters, in which we look forward to the upcoming annual conference in Princeton, New Jersey, and also look back on the ALSCW’s activities and accomplishments during 2010. In her President’s Column (see page 2), Susan Wolfson gives us her extensive report and reflections on VOLUME 3.4 YEAR-END 2010 the year. Inside This Issue I have always seen the ALSCW’s greatest strength in the variety of its endeavors—scholarly, academic, creative, pedagogical, and so on—and therefore the 2 The President’s Column: range of its appeal. This is particularly highlighted by the The Year Past, The Year Ahead fascinating array of publications produced by individual 4 News and Announcements: members of the Association in a given year. This fall, ALSCW/VSC LiT Forum when Susan alerted me to the publication of her new Local Meeting Baton Rouge book, Romantic Interactions (Johns Hopkins, October 2010), she and I realized that in fact several members Campion Receives Poetry Prize who have or will soon hold the office of President within Local Meeting Boston - Nelson the Association have had important works published in Local Meeting Boston - Basile 2010. And so, in this “From the Editor” I offer you a year- Forum 4 Released in-review of ALSCW presidential publications. Ricks To Receive Distinguished Scholar Award Warren Funds VSC Fellowship Morris Dickstein At the beginning of 2010, ’s New Publications by Members Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression (W.W. -

20Th Annual Conference 2016, Washington, DC (PDF)

ALSCW Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers 20th Annual Conference Oct. 27 –30, 2016 The Catholic University of America Washington, D.C. CONFERENCE COMMITTEE John Briggs , University of California-Riverside Lee Oser , College of the Holy Cross Ernest Suarez , Catholic Univeristy Rosanna Warren , University of Chicago SPECIAL THANKS TO Jeffrey Peters , Catholic University Joan Romano Shifflett , United States Naval Academy Ryan Wilson , Catholic University ALSCW The 20th Annual Conference of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers Oct. 27 –30, 2016 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS . .2 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS . .11 SUGGESTED LOCAL RESTAURANTS . .27 CAMPUS MAP . .28 Thursday, Oct. 27 4–7:15 p.m. AN EVENING OF READINGS Caldwell Hall Auditorium Cash bar and hors d’oeuvres beginning at 4 p.m., followed by readings by conference participants and this year’s Meringoff Fiction and Essay Award winners at 5 p.m. 7:30 –9 p.m. PLENARY READINGS (Open to the public) Caldwell Hall Auditorium Brad Leithauser , Johns Hopkins University Rosanna Warren , University of Chicago Friday, Oct. 28 7:15 a.m. REGISTRATION Caldwell Hall Foyer Registration with continental breakfast. 8–10 a.m. SEMINAR SESSION I SEMINAR 1 Robert Penn Warren and Time Caldwell Hall Auditorium MODERATORS Joan Romano Shifflett, U.S. Naval Academy Ryan Wilson , The Catholic University of America > Christine Casson , Emerson College, “Time and History in the Lyric Sequence: Robert Penn Warren’s Audubon: A Vision ” > William Bedford Clark , Texas A&M University, “Time, -

Fugitive and Agrarian Collection Addition Finding

Fugitive and Agrarian Collection Addition MSS 622 Arranged and described in Spring/Summer 2010 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Jean and Alexander Heard Library Vanderbilt University 419 21st. Avenue South Nashville, Tennessee 37203 Telephone: (615) 322-2807 © 2012 Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives Scope and Content Note This collection, 3.34 linear feet, is an addition to the Fugitive and Agrarian Collection MSS 160. It includes a wide range of items relating to the Fugitive and Agrarian groups and is especially valuable in the holdings of items from the 1980’s and 1990’s including correspondence, articles, book reviews, and other materials. In addition to the Fugitives and Agrarians themselves, whose biographical notes follow below, associates represented in this collection include: William T. Bandy Arthur Mizener Richmond Croom Beatty Flannery O’Connor Melvin E. Bradford Katherine Anne Porter Cleanth Brooks Sister Bernetta Quinn Wyatt Cooper Louis D. Rubin, Jr. Louise Cowan James Seay James Dickey Jesse Stuart Fellowship of Southern Writers Isabella Gardner Tate Ford Madox Ford Peter Taylor George Garrett Rosanna Warren Caroline Gordon Richard Weaver M. Thomas Inge Eudora Welty Randall and Mary Jarrell Kathryn Worth (Mrs. W. C. Curry) Robert Lowell David McDowell Biographical Notes Walter Clyde Curry Walter Clyde Curry received his B.A. from Wofford College in 1909 and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Stanford University in 1913 and 1915, respectively. Upon his graduation from Stanford, he accepted a faculty position at Vanderbilt University in 1915 and remained until 1955, when he retired from active teaching. During the last thirteen years of his stay at Vanderbilt, he served as chairman of the English department. -

Twentieth-Century Southern Literature

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 1997 Twentieth-Century Southern Literature J. A. Bryant Jr. University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bryant, J. A. Jr., "Twentieth-Century Southern Literature" (1997). Literature in English, North America. 12. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/12 NEW PERSPECTIVES ON THE SOUTH Charles P Roland, General Editor This page intentionally left blank Twentieth-Century Southern Literature J. A. BRYANT JR. THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1997 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bryant, J. A. (Joseph Allen), 1919– Twentieth-century southern literature / J.A. -

2016 Conference Program

ALSCWprogram_text.qxp_Layout 1 10/14/16 4:12 PM Page 1 ALSCW The 20th Annual Conference of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers Oct. 27–30, 2016 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS . .2 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS . .11 SUGGESTED LOCAL RESTAURANTS . .27 CAMPUS MAP . .28 ALSCWprogram_text.qxp_Layout 1 10/14/16 4:12 PM Page 2 Thursday, Oct. 27 4–7:15 p.m. AN EVENING OF READINGS Caldwell Hall Auditorium Cash bar and hors d’oeuvres beginning at 4 p.m., followed by readings by conference participants and this year’s Meringoff Fiction and Essay Award winners at 5 p.m. 7:30–9 p.m. PLENARY READINGS (Open to the public) Caldwell Hall Auditorium Brad Leithauser, Johns Hopkins University Rosanna Warren, University of Chicago Friday, Oct. 28 7:15 a.m. REGISTRATION Caldwell Hall Foyer Registration with continental breakfast. 8–10 a.m. SEMINAR SESSION I SEMINAR 1 Robert Penn Warren and Time Caldwell Hall Auditorium MODERATORS Joan Romano Shifflett, U.S. Naval Academy Ryan Wilson, The Catholic University of America > Christine Casson, Emerson College, “Time and History in the Lyric Sequence: Robert Penn Warren’s Audubon: A Vision” > William Bedford Clark, Texas A&M University, “Time, Eternity, and Memory: Warrenesque Variations on Augustinian Themes” > Mary E. Cuff, The Catholic University of America, “‘Sniffing the Dead Rat’: Herman Melville’s Influence on Robert Penn Warren” > Matthew Buckley Smith, Independent Scholar, “Practice for Eternity: Impermanence and the Poems of Robert Penn Warren” > Victor Strandberg, Duke University, “Robert Penn Warren -

Robert Penn Warren/ William Meredith Correspondence 1962- 1980

ROBERT PENN WARREN AND WILLIAM MEREDITH CORRESPONDENCE 1962-1980 MSS # 490 Arranged and described by Molly Dohrmann July 2006 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Jean and Alexander Heard Library Vanderbilt University 419 21st. Avenue South Nashville, Tennessee 37240 Telephone: (615) 322-2807 ROBERT PENN WARREN/ WILLIAM MEREDITH CORRESPONDENCE 1962- 1980 Biographical Notes William Meredith (January 9, 1919-- ) born in New York City is an American poet. He graduated from Princeton University in 1940 and later taught at Princeton, the University of Hawaii, and Connecticut College. He has published nine volumes of poetry and in 1988 won the Pulitzer Prize for Partial Accounts: New and Selected Poems (1987) and in 1997 the National Book Award for Effort at Speech. This collection is an archive of his personal correspondence with Robert Penn Warren, Eleanor Clark Warrren, and their daughter Rosanna. Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905- September 15, 1989) was born in Guthrie, Kentucky where he grew up. He graduated from Vanderbilt University in 1925. While at Vanderbilt he was associated with the Fugitive poets and later contributed to I’ll Take My Stand a manifesto of the Southern Agrarians. He studied also at the University of California and Yale. In 1928 he entered New College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and took a B.Litt. degree from there in 1930. He taught at Vanderbilt, Southwestern at Memphis, Louisiana State University, the University of Minnesota, and at Yale. In 1952 he married his second wife the novelist Eleanor Clark and they had two children Rosanna Phelps Warren (July 1953--) and Gabriel Penn Warren ( July 1955--). -

Literary Matters the Newsletter of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers Aut Nuntiarea Aut Delectare

Literary Matters THE NEWSLETTER OF THE ASSociation OF LITERARY SCHOLARS, CRITICS, AND WRITERS Aut nuntiarea aut delectare FROM THE EDITOR VOLUME 8.1 FALL/WINTER 2015 Whenever the New Year approaches, people begin taking stock, reminiscing, and finding ways to evaluate what progress has been made over the many months Inside This Issue since the last time they performed this same routine. With all of the ushering in of the new and different, we must be cautious not to overlook the value of the old; we 1 Letter from the Editor must avoid the temptation to prioritize change over and above maintaining what still works; we must consider 4 News and Announcements the benefits of retaining some of what was in favor of 14 Local Meeting Reports any and all glittery could-bes we think await us. That is not to say change is bad—quite the contrary, change is 17 Two Takes on a Talk necessary and has the potential to be wonderful. For 20 Book Reviews instance, in our very own organization, some substantial evolution is in progress, and the outcome promises to be 29 The Great Gatsby and the Wonder of a better, stronger association with greater staying power. the Green Light, John Wallen We are all indebted to the officers and executive council, along with those at the Catholic University of America, 32 New Publications by Members for the bright future they’ve constructed for the ALSCW. 39 Meringoff High School Essay Award: Those acknowledgements now made, I return to the The Winning Pieces, Sophie Stark initial project, which is the assessing of past attitudes, and Sylvie Thode behaviors, and lessons, and figuring out what to keep, not 45 Poets' Corner only what to change. -

The Poetic Vision of Robert Penn Warren

The Poetic Vision of Robert Penn Warren The University Press of Kentucky To Anne and Susan, And with thanks to Penny for her encouragement and support Man lives by images. They Lean at us from the world's wall, and Time's. --"Reading Late at Night, Thermometer Falling" ISB~: 0-8131-1347-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card number: 76-9503 Copyright © 1977 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 Web site: www.kentuckypress.com 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 4 I. Introduction: The Critical Reckoning 6 II. The Themes of Robert Penn Warren 29 Passage 29 The Undiscovered Self 32 Mysticism 36 In Context: Warren's Criticism 43 III. Poems of Passage 58 IV. The Undiscovered Self 143 V. Mysticism 221 VI. Postscript: An Appreciation 296 Some Notes on Verse Texture 297 The Question of “Place” 310 Notes 320 NOTE: (January 2012) I thank the University Press of Kentucky for its permission to put this book online. For easier readability, I have converted the text to a Microsoft Word format. Because computers now have a search function, I have also removed the Index. 3 Preface I have written this book in pursuit of two purposes. First, I have tried to elucidate Warren's poetry through a close study of a great number of individual poems, because the fact is that, after over half a century of prolific creativity as a poet, Warren is not very well or very widely understood, though he is good enough that he ought to be. -

About the Circle (Volume 1) Robert Penn Warren Studies [email protected]

Robert Penn Warren Studies Volume 1 Article 14 2001 About the Circle (Volume 1) Robert Penn Warren Studies [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/rpwstudies Part of the American Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Warren Studies, Robert Penn (2001) "About the Circle (Volume 1)," Robert Penn Warren Studies: Vol. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/rpwstudies/vol1/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Penn Warren Studies by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVISORY GROUP TO THE CENTER THE ROBERT PENN WARREN CIRCLE FOR ROBERT PENN WARREN STUDIES Formed in I 989, the Robert Penn Warren Circle honors the life and work Western Kentucky University of �o�ert Penn Warren. Although it is an autonomous organization, it part1c1pates each year with the American Literature Association and The Advisory Group to the Center for Robert Penn Warren Studies maintains a close affiliation with the Center for Robert Penn Warren serves as a think-tank in offeringsuggestions to the Center for activities Studies at Western Kentucky University and the Robert Penn Warren related to Robert Penn Warren and the study of his works. One of those Birthplac� Museum in Guthrie, Kentucky. Its membership is open to any suggestions became the annual Robert Penn Warren/Cleanth Brooks one who ts mterested m the works of Warren. For more information Award in 1995. about membership, please write Anthony Szczesiul, Department of Engh sh, University of Massachusetts-Lowell, Lowell, MA O I 854. -

2006 EDITORS Daniel Kempton, Director of English Graduate Studies H

Shawangunk Review State University of New York at New Paltz New Paltz, New York Volume XVII Spring 2006 EDITORS Daniel Kempton, Director of English Graduate Studies H. R. Stoneback, Department of English GUEST EDITOR for the SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL ENGLISH GRADUATE SYMPOSIUM and ROBERT PENN WARREN MATERIALS H. R. Stoneback TheShawangunk Review is the journal of the English Graduate Program at the State University of New York, New Paltz. TheReview publishes the proceedings of the annual English Graduate Symposium and literary articles by graduate students as well as poetry, fiction, and book reviews by students and faculty. The views expressed in the Shawangunk Review are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of English at SUNY New Paltz. Please address corre- spondence to Shawangunk Review, Department of English, SUNY New Paltz, New Paltz, NY 256. Copyright © 2006 Department of English, SUNY New Paltz. All rights reserved. Table of Contents From the Editors Introduction I The Robert Penn Warren Centennial Symposium H. R. STONEBACK Keynote Addresses II 4 Purity, Panic, and Pasiphaë in Brother to Dragons JOHN BURT 24 Shadowing Old Red: The Editor as Gumshoe WILLIAM BEDFORD CLARK Distinguished Guest Panelists III 3 A Tribute to Robert Penn Warren from New Paltz RICHARD ALLAN DAVISON 33 The Prose and Poetry of Robert Penn Warren DONALD JUNKINS 36 Who Were Chief Joseph & the Nez Perce? ROBERT W. LEWIS (Why Did RPW Write About Them)? Symposium Papers IV 38 Discovering the Sacred Light of Secular Conditions: MICHAEL BEILFUSS Coleridge’s Light of Imagination in Warren’s Criticism and Poetry 44 “I Require of You Only to Look”: Warren’s Mystical Vision WILLIAM BOYLE 50 “Depth and Shimmer” or “The Secret of Contact” NICOLE CAMASTRA in Elizabeth Madox Roberts and Robert Penn Warren 56 Sweeter than Hope: A Dantean Journey D. -

2018 Conference Program

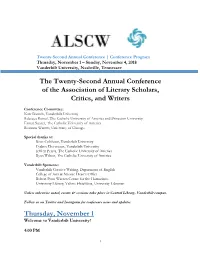

Twenty-Second Annual Conference | Conference Program Thursday, November 1 – Sunday, November 4, 2018 Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee The Twenty-Second Annual Conference of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers Conference Committee: Kate Daniels, Vanderbilt University Rebecca Rainof, The Catholic University of America and Princeton University Ernest Suarez, The Catholic University of America Rosanna Warren, University of Chicago Special thanks to: Rene Colehour, Vanderbilt University Cydnee Devereaux, Vanderbilt University Jeffrey Peters, The Catholic University of America Ryan Wilson, The Catholic University of America Vanderbilt Sponsors: Vanderbilt Creative Writing, Department of English College of Arts & Science Dean’s Office Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities University Library, Valerie Hotchkiss, University Librarian Unless otherwise noted, events & sessions take place in Central Library, Vanderbilt campus. Follow us on Twitter and Instagram for conference news and updates. Thursday, November 1 Welcome to Vanderbilt University! 4:00 PM 1 REGISTRATION Central Library Lobby An Evening of Readings 5:00-6:15 PM Readings by this year’s Meringoff Award Winners Community Room Central Library 7:00 PM PLENARY READING Community Room Central Library Introduction: Rosanna Warren, University of Chicago Mark Jarman, Centennial Professor of English, Vanderbilt University Friday, November 2 7:45 AM REGISTRATION Coffee and Tea Bar (7:45 am-10:30 am) Central Library Lobby 8:15 AM-10:15 AM PLENARY SESSION I Community Room Central Library Welcome from Bonnie Dow, Dean of Academic Initiatives, College of Arts & Science, Vanderbilt University, Community Room Central Library Beyond the Black and White Binary: the Latinx Literary Presence in the South Moderator: Lorraine Lopez, Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor, Vanderbilt University 1) Fred Arroyo, Middle Tennessee State University, "Sown in Earth: Bloodlines North and South” 2) Lorraine M.