The Poetic Vision of Robert Penn Warren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN Norman, Oklahoma 2009 SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ________________________ Prof. Paul A. Gilje, Chair ________________________ Prof. Catherine E. Kelly ________________________ Prof. Judith S. Lewis ________________________ Prof. Joshua A. Piker ________________________ Prof. R. Richard Hamerla © Copyright by ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN 2009 All Rights Reserved. To my excellent and generous teacher, Paul A. Gilje. Thank you. Acknowledgements The only thing greater than the many obligations I incurred during the research and writing of this work is the pleasure that I take in acknowledging those debts. It would have been impossible for me to undertake, much less complete, this project without the support of the institutions and people who helped me along the way. Archival research is the sine qua non of history; mine was funded by numerous grants supporting work in repositories from California to Massachusetts. A Friends Fellowship from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies supported my first year of research in the Philadelphia archives and also immersed me in the intellectual ferment and camaraderie for which the Center is justly renowned. A Dissertation Fellowship from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History provided months of support to work in the daunting Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. The Chandis Securities Fellowship from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens brought me to San Marino and gave me entrée to an unequaled library of primary and secondary sources, in one of the most beautiful spots on Earth. -

•Da Etamettez

:f-liEer all is said and done, more is said than done. igdom al MISSIONARY PREMILLENNIAL BIBLICAL BAPTISTIC ind thee "I Should Like To Know" shall cad fire: thee 1. Is it Scriptural to send out abound." He wrote Timothy to lashing 01, women missionaries? come by Bro. Carpus' and bring Etamettez his old coat he had left there. •da Personally, I don't think much urnace of the practice. However, such the gnash' 3. Does the "new heart" spoken could be done Scripturally. Of of in Ezek. 11:19 have reference .ed moatO Paid Girculalien 7n Rii stales and 7n Many Foreign Gouniries course their work should be con- iosts that to the divine nature implanted in testimony; if they speak not according to this word fined to the limits set by the Holy man at the new birth? , beloved, "To the law and to the Spirit in the New Testament. But I says, it is because there is no light in them."-Isaiah 8:29. Paul mentions by name as his Yes. II Pet. 1:4. In repentance .1 into the helpers on various mission fields, we die to sin and the old life; in Phoebe, Priscilla, Euodias, Synty- faith we receive Christ who is our Is us of 1 VOL. 23, NO. 51 RUSSELL, KENTUCKY, JANUARY 22, 1955 WHOLE NUMBER 868 che and others. In Romans 16 he new life. Col. 3:3-4. John 1:12-13. this world mentions a number of women, I John 5:10-13. Our headship fullest Who evidently were workers on passes from self to Christ. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

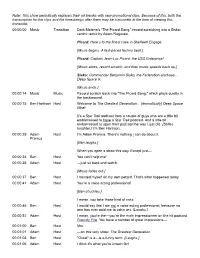

Greatest Generation

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:14 Music Music Record scratch back into "The Picard Song," which plays quietly in the background. 00:00:15 Ben Harrison Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation... [dramatically] Deep Space Nine! It's a Star Trek podcast from a couple of guys who are a little bit embarrassed to have a Star Trek podcast. And a little bit embarrassed to open their podcast the way I just did. [Stifles laughter.] I'm Ben Harrison. 00:00:29 Adam Host I'm Adam Pranica. There's nothing I can do about it. Pranica [Ben laughs.] When you open a show this way. Except just— 00:00:34 Ben Host You can't help me! 00:00:35 Adam Host —just sit back and watch. [Music fades out.] 00:00:37 Ben Host I hoisted myself on my own petard. That's what happened today. 00:00:41 Adam Host You're a voice acting professional! [Ben chuckles.] I mean, you take those kind of risks. -

Mccrimmon Mccrimmon

ISSUE #14 APRIL 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE MARC PLATT chats about Point of Entry RICHARD EARL on his roles in Doctor Who and Sherlock Holmes MAGGIE staBLES is back in the studio as Evelyn Smythe! RETURN OF THE McCRIMMON FRazER HINEs Is baCk IN THE TaRdIs! PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL Well, as you read this, Holmes and the Ripper will I do adore it. But it is all-consuming. And it reminded finally be out. As I write this, I have not long finished me of how hard the work is and how dedicated all our doing the sound design, which made me realize one sound designers are. There’s quite an army of them thing in particular: that being executive producer of now. When I became exec producer we only had a Big Finish really does mean that I don’t have time to do handful, but over the last couple of years I have been the sound design for a whole double-CD production. on a recruitment drive, and now we have some great That makes me a bit sad. But what really lifts my spirits new people with us, including Daniel Brett, Howard is listening to the music, which is, at this very moment, Carter, Jamie Robertson and Kelly and Steve at Fool being added by Jamie Robertson. Only ten more Circle Productions, all joining the great guys we’ve been minutes of music to go… although I’m just about to working with for years. Sound design is a very special, download the bulk of Part Two in a about half an hour’s crazy world in which you find yourself listening to every time. -

POEMS for REMEMBRANCE DAY, NOVEMBER 11 for the Fallen

POEMS FOR REMEMBRANCE DAY, NOVEMBER 11 For the Fallen Stanzas 3 and 4 from Lawrence Binyon’s 8-stanza poem “For the Fallen” . They went with songs to the battle, they were young, Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them. Robert Laurence Binyon Poem by Robert Laurence Binyon (1869-1943), published in by the artist William Strang The Times newspaper on 21st September 1914. Inspiration for “For the Fallen” Laurence Binyon composed his best-known poem while sitting on the cliff-top looking out to sea from the dramatic scenery of the north Cornish coastline. The poem was written in mid-September 1914, a few weeks after the outbreak of the First World War. Laurence said in 1939 that the four lines of the fourth stanza came to him first. These words of the fourth stanza have become especially familiar and famous, having been adopted as an Exhortation for ceremonies of Remembrance to commemorate fallen service men and women. Laurence Binyon was too old to enlist in the military forces, but he went to work for the Red Cross as a medical orderly in 1916. He lost several close friends and his brother-in-law in the war. . -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

Hip to Post45

DAVID J. A L WORTH Hip to Post45 Michael Szalay, Hip Figures: A Literary History of the Democratic Party. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012. 324 pp. $24.95. here are we now?” About five years [ ] have passed since Amy Hungerford “ W asked this question in her assess- ment of the “revisionary work” that was undertaken by literary historians at the dawn of the twenty- first century.1 Juxtaposing Wendy Steiner’s contribution to The Cambridge History of American Literature (“Postmodern Fictions, 1970–1990”) with new scholarship by Rachel Adams, Mark McGurl, Deborah Nelson, and others, Hungerford aimed to demonstrate that “the period formerly known as contemporary” was being redefined and revitalized in exciting new ways by a growing number of scholars, particularly those associated with Post45 (410). Back then, Post45 named but a small “collective” of literary historians, “mainly just finishing first books or in the middle of second books” (416). Now, however, it designates something bigger and broader, a formidable institution dedi- cated to the study of American culture during the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. This institution comprises an ongoing sequence of academic conferences (including a large 1. Amy Hungerford, “On the Period Formerly Known as Contemporary,” American Literary History 20.1–2 (2008) 412. Subsequent references will appear in the text. Contemporary Literature 54, 3 0010-7484; E-ISSN 1548-9949/13/0003-0622 ᭧ 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System ALWORTH ⋅ 623 gathering that took place at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2011), a Web-based journal of peer-reviewed scholarship and book reviews (Post45), and a monograph series published by Stanford University Press (Post•45). -

Postsecular Sermons in Contemporary American Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Spring 6-30-2011 The Sermonic Urge: Postsecular Sermons in Contemporary American Fiction Peter W. Rorabaugh Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rorabaugh, Peter W., "The Sermonic Urge: Postsecular Sermons in Contemporary American Fiction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/75 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SERMONIC URGE: POSTSECULAR SERMONS IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN FICTION by PETER W. RORABAUGH Under the Direction of Christopher Kocela ABSTRACT Contemporary American novels over the last forty years have developed a unique orientation toward religious and spiritual rhetoric that can best be understood within the multidisciplinary concept of the postsecular. In the morally-tinged discourse of their characters, several esteemed American novelists (John Updike, Toni Morrison, Louise Erdrich, and Cormac McCarthy) since 1970 have used sermons or sermon-like artifacts to convey postsecular attitudes and motivations. These postsecular sermons express systems of belief that are hybrid, exploratory, and confessional in nature. Through rhetorical analysis of sermons in four contemporary American novels, this dissertation explores the performance of postsecularity in literature and defines the contribution of those tendancies to the field of literary and rhetorical studies. INDEX WORDS: Postsecular, Postmodern, Christianity, American literature, Sermon, Religious rhetoric, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Louise Erdrich, John Updike, Cormac McCarthy, Kenneth Burke, St. -

AIKEN, CONRAD, 1889-1973. Conrad Aiken Collection, 1951-1962

AIKEN, CONRAD, 1889-1973. Conrad Aiken collection, 1951-1962 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Aiken, Conrad, 1889-1973. Title: Conrad Aiken collection, 1951-1962 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 126 Extent: .25 linear ft. (1 box) Abstract: Collection of materials relating to American poet and critic, Conrad Aiken including correspondence and printed material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Henry E. Huntington Library (San Marino, CA) and Houghton Library, Harvard University. Source Purchased from George Minkoff Booksellers in 1977. Additions were purchased from Charles Apfelbaum Rare Manuscripts and Archives in 2006. Custodial History Purchased from dealer, provenance unknown. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Conrad Aiken collection, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Conrad Aiken collection, 1951-1962 Manuscript Collection No. 126 Appraisal Note Acquired by Director of the Rose Library, Linda Matthews, as part of the Rose Library's holdings in American literature. Processing Processed by Linda Matthews, December 15, 1977. This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. Please refer to the Rose Library's harmful language statement for more information about why such language may appear and ongoing efforts to remediate racist, ableist, sexist, homophobic, euphemistic and other oppressive language. -

NOR 15-Final.Pdf

New Orleans Review Spring 1988 Editors John Biguenet· John Mosier Managing Editor Sarah Elizabeth Spain Design Vilma Pesciallo Contributing Editors Bert Cardullo David Estes Jacek Fuksiewicz Alexis Gonzales, F.S.C. Bruce Henricksen Andrew Horton Peggy McCormack Rainer Schulte Founding Editor Miller Williams Advisory Editors Richard Berg Doris Betts Joseph Fichter, S.J. John Irwin Murray Krieger Frank Lentricchia Raymond McGowan Wesley Morris Walker Percy Herman Rapaport Robert Scholes Marcus Smith Miller Williams The New Orleans Review is published by Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118, United States. Copyright© 1988 by Loyola University. Critical essays relating to film or literature of up to ten thousand words should be prepared to conform with the new MLA guidelines and sent to the appropriate editor, together with a stamped, self-addressed envelope. The address is New Orleans Review, Box 195, Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118. Fiction, poetry, photography or related artwork should be sent to the Art and Literature Editor. A stamped, self-addressed envelope should be enclosed. Reasonable care is taken in the handling of material, but no responsibility is assumed for the loss of unsolicited material. Accepted manuscripts are the property of the NOR. The New Orleans Review is published in February, May, August, and November. Annual Subscription Rate: Institutions $30.00, Individuals $25.00, Foreign Subscribers $35.00. Contents listed in the PMLA Bibliography and the Index of American Periodical Verse. US ISSN 0028-6400 Photographs of Gwen Bristow, Ada Jack Carver, Dorothy Dix, and Grace King are reproduced courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection, Museum/Research Center, Acc. -

Librarian of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Media Relations UNH Publications and Documents 8-2-2007 Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate Erika Mantz UNH Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/news Recommended Citation Mantz, Erika, "Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate" (2007). UNH Today. 850. https://scholars.unh.edu/news/850 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNH Publications and Documents at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Relations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate 9/11/17, 1250 PM Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate Contact: Erika Mantz 603-862-1567 UNH Media Relations August 2, 2007 Librarian of Congress James H. Billington has announced the appointment of Charles Simic to be the Library’s 15th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry. Simic will take up his duties in the fall, opening the Library’s annual literary series on Oct. 17 with a reading of his work. He also will be a featured speaker at the Library of Congress National Book Festival in the Poetry pavilion on Saturday, Sept. 29, on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Simic succeeds Donald Hall as Poet Laureate and joins a long line of distinguished poets who have served in the position, including most recently Ted Kooser, Louise Glück, Billy Collins, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Pinsky, Robert Hass and Rita Dove.