Twentieth-Century Southern Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

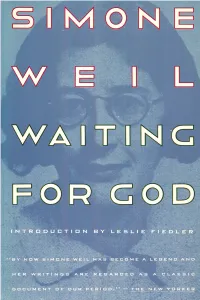

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

University Interscholastic League Literary Criticism Contest • Invitational a • 2021

University Interscholastic League Literary Criticism Contest • Invitational A • 2021 Part 1: Knowledge of Literary Terms and of Literary History 30 items (1 point each) 1. A line of verse consisting of five feet that char- 6. The repetition of initial consonant sounds or any acterizes serious English language verse since vowel sounds in successive or closely associated Chaucer's time is known as syllables is recognized as A) hexameter. A) alliteration. B) pentameter. B) assonance. C) pentastich. C) consonance. D) tetralogy. D) resonance. E) tetrameter. E) sigmatism. 2. The trope, one of Kenneth Burke's four master 7. In Greek mythology, not among the nine daugh- tropes, in which a part signifies the whole or the ters of Mnemosyne and Zeus, known collectively whole signifies the part is called as the Muses, is A) chiasmus. A) Calliope. B) hyperbole. B) Erato. C) litotes. C) Polyhymnia. D) synecdoche. D) Urania. E) zeugma. E) Zoe. 3. Considered by some to be the most important Irish 8. A chronicle, usually autobiographical, presenting poet since William Butler Yeats, the poet and cele- the life story of a rascal of low degree engaged brated translator of the Old English folk epic Beo- in menial tasks and making his living more wulf who was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize for through his wit than his industry, and tending to Literature is be episodic and structureless, is known as a (n) A) Samuel Beckett. A) epistolary novel. B) Seamus Heaney. B) novel of character. C) C. S. Lewis. C) novel of manners. D) Spike Milligan. D) novel of the soil. -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

Nature As Mystical Reality in the Fiction of Cormac Mccarthy Skyler Latshaw Grand Valley State University

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 8-2013 Burning on the Shore of an Unknowable Void: Nature as Mystical Reality in the Fiction of Cormac McCarthy Skyler Latshaw Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Latshaw, Skyler, "Burning on the Shore of an Unknowable Void: Nature as Mystical Reality in the Fiction of Cormac McCarthy" (2013). Masters Theses. 64. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Burning on the Shore of an Unknowable Void: Nature as Mystical Reality in the Fiction of Cormac McCarthy Skyler Latshaw A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts English Literature August 2013 Abstract Language, spirituality, and the natural world are all prominent themes in the novels of Cormac McCarthy. This thesis examines the relationship between the three themes, arguing that McCarthy empowers the natural world with a spiritual significance that may be experienced by humanity, but not completely understood or expressed. Man, being what Kenneth Burke describes as the “symbol-using” animal, cannot express reality through language without distorting it. Language also leads to the commodification of the natural world by allowing man to reevaluate the reality around him based on factors of his own devising. -

The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac Mccarthy's Blood Meridian

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 8-1-2014 The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian Ryan Joseph Tesar University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Repository Citation Tesar, Ryan Joseph, "The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2218. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/6456449 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF HERMAN MELVILLE’S MOBY-DICK ON CORMAC MCCARTHY’S BLOOD MERIDIAN by Ryan Joseph Tesar Bachelor of Arts in English University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts – English Department of English College of Liberal Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2014 Copyright by Ryan Joseph Tesar, 2014 All Rights Reserved - THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Ryan Joseph Tesar entitled The Influence of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts - English Department of English John C. -

Episode 113: a Place Worse Than Hell Week of December 2 – 8, 1862

Episode 113: A Place Worse Than Hell Week of December 2 – 8, 1862 http://civilwar150.longwood.edu “If there is a worse place than hell,” Lincoln told a visitor in December 1862, “I am in it.” The fall state and congressional elections had not gone well. Radical Republicans, angered that the President had remained loyal to McClellan so long, failed to campaign wholeheartedly, leaving the field to the Democrats, who accused the administration of incompetence on the battlefield and of unconstitutional abuse of its power, both in curbing dissent and in daring to speak of freeing slaves. Asked for his reaction to all this bad news, Lincoln said he felt like the boy who stubbed his toe – he was too big to cry, and it hurt too much to laugh. “The fact is that the country is done for unless something is done at once…..” said Senator Zachariah Chandler. “The President is a weak man, too weak for the occasion, and those fool or traitor generals are wasting time and yet more precious blood in indecisive battles and delays.” Rumors circulated that Lincoln would resign in favor of Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, and that McClellan would somehow be recalled to Washington to assume dictatorial power. This attack on his leadership by men of his own party at such a critical time deeply distressed Lincoln: “We are now on the brink of destruction,” he told an aide. “It appears to me that the Almighty is against us.” Generally the public press supported the President. The Washington Chronicle saw “a perfect balance of thoroughly sound faculties, great calmness of temper, firmness of purpose, supreme moral principle and intense patriotism”. -

Plantation Slavery and Economic Development in the Antebellum Southern United States

Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 3Plantation No. 3, July 2003, Slavery pp. 289–332. and Economic Development 289 Plantation Slavery and Economic Development in the Antebellum Southern United States CHARLES POST The relationship of plantation slavery in the Americas to economic and social development in the regions it was dominant has long been a subject of scholarly debate. The existing literature is divided into two broad interpretive models – ‘planter capitalism’ (Fogel and Engerman, Fleisig) and the ‘pre-bourgeois civilization’ (Genovese, Moreno-Fraginals). While each grasps aspects of plantation slavery’s dynamics, neither provides a consistent and coherent his- torical or theoretical account of slavery’s impact on economic development because they focus on the subjective motivations of economic actors (planters or slaves) independent of their social context. Borrowing Robert Brenner’s concept of ‘social property relations’, the article presents an alternative analysis of the dynamics of plantation slavery and their relation to economic develop- ment in the regions it dominated. Keywords: plantation slavery, capitalism, USA, world market, agrarian class structure INTRODUCTION From the moment that plantation slavery came under widespread challenge in Europe and the Americas in the late eighteenth century, its economic impact has been hotly debated. Both critics and defenders linked the political and moral aspects of slavery with its social and economic effects on the plantation regions Charles Post, Sociology Department, Sarah Lawrence College, 1 Mead Way, Bronxville, NY 10708- 5999, USA. e-mail: [email protected] (until 30 August 2003). Department of Social Science, Borough of Manhattan Community College-CUNY, 199 Chambers Street, New York, NY 10007, USA. -

Scutokyosyllabus for 2014FINAL

Santa Clara University School of Law Center for Global Law and Policy 2015 Tokyo Summer Program At Asia Center of Japan, June 8 – June 12, 2015 Introduction to Japanese Law Professor Yasuhei TANIGUCHI, LL.M. Berkeley 1963 & J.S.D.Cornell, 1964 Prof. Em. of Kyoto University and Of Counsel, Matsuo & Kosugi, Tokyo This course follows the Prof. Abe’s course of the same title and tries to approach the Japanese legal system from a slightly different perspective. Emphasis will be on general subjects such as historical developments, constitutional schemes, judiciary and legal professions, dispute resolution, etc. rather than on specific topics of practical interest, which are to be dealt with in other courses. The instructor was born in 1934. His long personal experiences will be infused in the course hopefully to make the course historically interesting. A. Historical and Comparative Basis of Japanese Law It is important to understand the present Japanese law from a historical perspective. Japan experienced a radical legal reform at least twice in its modern history, firstly during Meiji period starting in 1868 under an influence of the European Civil Law and secondly after the defeat in the Pacific War under an influence of the American Common Law. The third wave of reform has visited Japan in the first decade of this century as the justice system reforms dealt with in C below. (1) Tokugawa Law (1603-1868) 1. John H. WIGMORE, A PANORAMA OF THE WORLD’S LEGAL SYSTEMS (1936), VII Japanese Legal System (III) Third Period, pp. 479-525 2. DAN F. HENDERSON, CONCILIATION AND JAPANESE LAW – TOKUGAWA AND MODERN Vol. -

Freedom! to Americans the Word Freedom Is Special, Almost Sacred

Freedom! Page 1 of 3 Freedom! To Americans the word freedom is special, almost sacred. Two hundred twenty-nine years ago, our forefathers placed their names on a document, which jeopardized their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor. It’s not that we own the word freedom, but among all the peoples of the earth we appreciate it with gratitude. There are so many beautiful aspects of being a free people that we celebrate. Like a kaleidoscope, full of multiple colors, I praise God for the hue that assures us the right and privilege to express ourselves. This is what The First Amendment is all about. As we approach this commemorative July fourth celebration, nostalgia overcomes me. This past week we were informed of the passing of the First Lady of American Fundamentalism, Mrs. Lee Roberson, the beloved wife of Dr. Lee Roberson, former pastor of Highland Park Baptist Church and founder of Tennessee Temple Schools. They were married sixty-eight years. I still remember when she spoke our Mother-Daughter Banquet. Our girls were young and my wife was especially happy to have her since she attended Tennessee Temple University. My mother-in-law said that among all the ladies that spoke to our ladies, Mrs. Roberson was perhaps her favorite, because although she was a lady of grace yet she was also down-to-earth. Through the years I was blessed to have my path cross with the Robersons. Though it may be hard to picture for some who did not know the royal family, when in private conversation, Mrs. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Cornell Alumni Magazine

c1-c4CAMja12_c1-c1CAMMA05 6/18/12 2:20 PM Page c1 July | August 2012 $6.00 Corne Alumni Magazine In his new book, Frank Rhodes says the planet will survive—but we may not Habitat for Humanity? cornellalumnimagazine.com c1-c4CAMja12_c1-c1CAMMA05 6/12/12 2:09 PM Page c2 01-01CAMja12toc_000-000CAMJF07currents 6/18/12 12:26 PM Page 1 July / August 2012 Volume 115 Number 1 In This Issue Corne Alumni Magazine 2 From David Skorton Generosity of spirit 4 The Big Picture Big Red return 6 Correspondence Technion, pro and con 5 10 10 From the Hill Graduation celebration 14 Sports Diamond jubilee 18 Authors Dear Diary 36 Wines of the Finger Lakes Hermann J. Wiemer 2010 Dry Riesling Reserve 52 Classifieds & Cornellians in Business 35 42 53 Alma Matters 56 Class Notes 38 Home Planet 93 Alumni Deaths FRANK H. T. RHODES 96 Cornelliana Who is Narby Krimsnatch? The Cornell president emeritus and geologist admits that the subject of his new book Legacies is “ridiculously comprehensive.” In Earth: A Tenant’s Manual, published in June by To see the Legacies listing for under - Cornell University Press, Rhodes offers a primer on the planet’s natural history, con- graduates who entered the University in fall templates the challenges facing it—both man-made and otherwise—and suggests pos- 2011, go to cornellalumnimagazine.com. sible “policies for sustenance.” As Rhodes writes: “It is not Earth’s sustainability that is in question. It is ours.” Currents 42 Money Matters BILL STERNBERG ’78 20 Teachable Moments First at the Treasury Department and now the White House, ILR grad Alan Krueger A “near-peer” year ’83 has been at the center of the Obama Administration’s response to the biggest finan- Flesh Is Weak cial crisis since the Great Depression. -

A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-23-2011 12:00 AM A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877 Marise Bachand University of Western Ontario Supervisor Margaret M.R. Kellow The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Marise Bachand 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Bachand, Marise, "A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 249. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/249 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SEASON IN TOWN: PLANTATION WOMEN AND THE URBAN SOUTH, 1790-1877 Spine title: A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South Thesis format: Monograph by Marise Bachand Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Marise Bachand 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Margaret M.R. Kellow Dr. Charlene Boyer Lewis ____________________ Dr. Monda Halpern ____________________ Dr. Robert MacDougall ____________________ Dr.