Yemen Six Month Economic Analysis Economic Warfare & The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macroeconomic Policies for Growth, Employment and Poverty Reduction in Yemen

Macroeconomic Policies for Growth, Employment and Poverty Reduction in Yemen i Copyright 2006 By the Sub-Regional Resource Facility for Arab States (SURF-AS) United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) UN House, Riad El-Solh Square P.O.Box: 11-3216 Beirut, Lebanon All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retreival sys- tem, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of UNDP/SURF-AS Design, Color Separation and Printing by Virgin Graphics Email: [email protected] ii Case Study Team Advisory Group Contributing Authors: Flavia Pansieri (Resident Representative, (Authors of background papers) UNDP Yemen) Ahmad Ghoneim: Trade Yahya Al Mutawakel (Vice Minister and Ahmad Kamaly: Fiscal Policy Head of the Poverty Reduction Strategy Anis Chowdhury: Monetary Policy Follow-up and Monitoring Unit, Ministry of Antoine Heuty: Fiscal Policy Planning and International Cooperation.) Farhad Mehran: Employment Moin Karim, (Former Deputy Resident Frederick Nixson: Trade and Industry Representative, UNDP Yemen) Haroon Akram-Lodhi: Agriculture Mohammad Pournik, (Senior Country Heba Nassar: Macroeconomics Economist, UNDP Yemen) Hyun Son: Poverty Ibrahim Saif: Industry Core Team John Roberts: Macroeconomics Massoud Karshenas (Team Leader and Karima Korayem: Agriculture and Poverty Principal Investigator, Professor of Khalid Abu-Ismail: Macroeconomics and Economics, SOAS, London) Poverty Khalid Abu-Ismail (Macroeconomics and Matias Vernengo: -

Enabling Poor Rural People to Overcome Poverty in Yemen

©IFAD/G. Ludwig Enabling poor rural people to overcome poverty in Yemen Rural poverty in Yemen The Republic of Yemen is one of the driest, poorest and least developed countries in the world. Poverty and food insecurity are strongly linked with the depletion and degradation of land and water resources. It is one of the most water-stressed countries in the world – each Yemeni’s average share of renewable water resources is about one tenth of the average in most Middle Eastern countries and one fiftieth of the world average. Poverty affects nearly 42 per cent of the country’s population and is mainly a rural phenomenon. Over 80 per cent of poor people reside in rural areas, and almost half of them live on less than US$2 a day. Small-scale farmers, sharecroppers, landless people, nomadic herders and artisanal fishers all suffer from inadequate access to basic necessities such as land, safe water, health care services and education. The population is young and growing rapidly. Two thirds of Yemenis are under 24 years old, and half are less than 15 years of age. More than 50 per cent of all children suffer from malnutrition. Women are also particularly disadvantaged. In addition to their heavy domestic workload, they provide 60 per cent of the labour in crop cultivation and more than 90 per cent in tending livestock. Despite their vital contributions to the rural economy, women have very limited access to economic, social and political opportunities. Many are illiterate and on average they earn 30 per cent less than men. -

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 15158-YEM Republic of Yemen Poverty Assessmzent Public Disclosure Authorized June26, 1996 Middl(e I st I IlImmi RemMIrcesD)ivi,(fln ( o LIltrV DX I IeeItII Middle East mindNorthi Africa Retgion Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank ClURRENCY EQuIVALENTS Currency Unit = Yemeni Rial (YR) YR 1.0 = 100 Fils Exchange Rate as of.June 1, 1996 Official exchange rate: YR II 5/US$ Parallel exchanigerate: YR I1 5/1US$ Yemen Fiscal Year January I - December 3 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS ARI Acute Respiratory Infectionis DHS Demographilc and Maternal and Child Health Survey EPI Expanded Program of Iin Inllnizationis FAO Food and Agriculture Organization GDP Gross Domestic Product GNP Gross National Product HBS-92 Household Budget Survey, 1992 LCCD Local Counicils for Cooperative Development LDA Local Developmenlt Association MOSL Ministry of Social Affairs, Social Insiuranice,and Labor NGO NongoverinmenltalOrgan ization OECD Organ isation for Economic Co-operation aiid Development PDRY Peoples' Democratic Republic of Yemen TFR Total Fertility Rate UNDP lUnited Nations Development Programine UNHCR ULited Nations High Commission for Reftugees WDR World Development Report YAR Yemen Arab Republic YR Yeienl Rial REPUBLIC OF YEMEN POVERTY ASSESSMENT TABLEOF CONTENTS i EXECUTIVESUMMARY ................................................................ I THE POVERTY PROFILE ................................................................ ,. 2 THE EXTENTAND DEPTHOF POVERTY....................................................................... -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

Yemen's Relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council

Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States ‘One blood and one destiny’? Yemen’s relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council Edward Burke June 2012 Number 23 The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a ten-year multidisciplinary global research programme. It focuses on topics such as globalization and the repositioning of the Gulf States in the global order, capital flows, and patterns of trade; specific challenges facing carbon-rich and resource-rich economic development; diversification, educational and human capital development into post-oil political economies; and the future of regional security structures in the post-Arab Spring environment. The Programme is based in the LSE Department of Government and led by Professor Danny Quah and Dr Kristian Ulrichsen. The Programme produces an acclaimed working paper series featuring cutting-edge original research on the Gulf, published an edited volume of essays in 2011, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students, and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. At the LSE, the Programme organizes a monthly seminar series, invitational breakfast briefings, and occasional public lectures, and is committed to five major biennial international conferences. The first two conferences took place in Kuwait City in 2009 and 2011, on the themes of Globalization and the Gulf, and The Economic Transformation of the Gulf. The next conference will take place at the LSE in March 2013, on the theme of The Arab Spring and the Gulf: Politics, Economics, and Security. The Programme is funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. -

Yemen and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States ‘One blood and one destiny’? Yemen’s relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council Edward Burke June 2012 Number 23 The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a ten-year multidisciplinary global research programme. It focuses on topics such as globalization and the repositioning of the Gulf States in the global order, capital flows, and patterns of trade; specific challenges facing carbon-rich and resource-rich economic development; diversification, educational and human capital development into post-oil political economies; and the future of regional security structures in the post-Arab Spring environment. The Programme is based in the LSE Department of Government and led by Professor Danny Quah and Dr Kristian Ulrichsen. The Programme produces an acclaimed working paper series featuring cutting-edge original research on the Gulf, published an edited volume of essays in 2011, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students, and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. At the LSE, the Programme organizes a monthly seminar series, invitational breakfast briefings, and occasional public lectures, and is committed to five major biennial international conferences. The first two conferences took place in Kuwait City in 2009 and 2011, on the themes of Globalization and the Gulf, and The Economic Transformation of the Gulf. The next conference will take place at the LSE in March 2013, on the theme of The Arab Spring and the Gulf: Politics, Economics, and Security. -

Institutional Change and the Egyptian Presence in Yemen 1962-19671

1 Importing the Revolution: Institutional change and the Egyptian presence in Yemen 1962-19671 Joshua Rogers Accepted version. Published 2018 in Marc Owen Jones, Ross Porter and Marc Valeri (eds.): Gulfization of the Arab World. Berlin, London: Gerlach, pp. 113-133. Abstract Between 1962 and 1967, Egypt launched a large-scale military intervention to support the government of the newly formed Yemen Arab Republic. Some 70,000 Egyptian military personnel and hundreds of civilian advisors were deployed with the stated aim to ‘modernize Yemeni institutions’ and ‘bring Yemen out of the Middle Ages.’ This article tells the story of this significant top-down and externally-driven transformation, focusing on changes in the military and formal government administration in the Yemen Arab Republic and drawing on hitherto unavailable Egyptian archival material. Highlighting both the significant ambiguity in the Egyptian state-building project itself, as well as the unintended consequences that ensued as Egyptian plans collided with existing power structures; it traces the impact of Egyptian intervention on new state institutions, their modes of functioning, and the articulation of these ‘modern’ institutions, particularly the military and new central ministries, with established tribal and village-based power structures. 1. Introduction On the night of 26 September 1962, a column of T-34 tanks trundled through the streets of Sana‗a and surrounded the palace of the new Imam of Yemen, Mu ammad al-Badr,2 who had succeeded his father Imam ‘ mad (r.1948-62) only one week earlier. Opening fire shortly before midnight, the Yemeni Free Officers announced the ‗26 September Revolution‘ on Radio Sana‗a and declared the formation of a new state: the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR). -

The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: the Elusive Road to Peace

Working Paper 18-1 By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace November 2018 The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark Working Paper 18-1 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publications Data The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: The elusive road to peace ISBN 978-1-927802-24-3 © 2018 Project Ploughshares First published November 2018 Please direct enquires to: Project Ploughshares 140 Westmount Road North Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G6 Canada Telephone: 519-888-6541 Email: [email protected] Editing: Wendy Stocker Design and layout: Tasneem Jamal Table of Contents Glossary of Terms i List of Figures ii Acronyms and Abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 4 Participants in the Conflict 6 Major local actors 6 Foreign and regional actors 7 Major arms suppliers 7 Summary of the Conflict (2011-2018) 8 Civil strife breaks out (January 2011 to March 2015) 8 The internationalization of conflict (2015) 10 An influx of weapons and more human-rights abuses (2016) 10 A humanitarian catastrophe (2017- June 2018) 13 The Scale of the Forgotten War 16 Battle-related deaths 17 Forcibly displaced persons 17 Conflict and food insecurity 22 Infrastructural collapse 23 Arming Saudi Arabia 24 Prospects for Peace 26 Regulation of Arms Exports 30 The Path Ahead and the UN 32 Conclusion 33 Authors 34 Endnotes 35 Photo Credits 41 Glossary of Terms Arms Trade Treaty: A multilateral treaty, which entered into force in December 2014, that establishes -

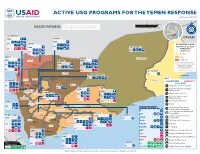

USG Yemen Complex Emergency Program

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE YEMEN RESPONSE Last Updated 02/12/20 0 50 100 mi INFORMA Partner activities are contingent upon access to IC TI PH O A N R U G SAUDI ARABIA conict-aected areas and security concerns. 0 50 100 150 km N O I T E G U S A A D ID F /DCHA/O AL HUDAYDAH IOM AMRAN OMAN IOM IPs SA’DAH ESTIMATED FOOD IPs SECURITY LEVELS IOM HADRAMAWT IPs THROUGH IPs MAY 2020 IPs Stressed HAJJAH Crisis SANA’A Hadramawt IOM Sa'dah AL JAWF IOM Emergency An “!” indicates that the phase IOM classification would likely be worse IPs Sa'dah IPs without current or planned IPs humanitarian assistance. IPs Source: FEWS NET Yemen IPs AL MAHRAH Outlook, 02/20 - 05/20 Al Jawf IP AMANAT AL ASIMAH Al Ghaedha IPs KEY Hajjah Amran Al Hazem AL MAHWIT Al Mahrah USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Marib IPs Hajjah Amran MARIB Agriculture and Food Security SHABWAH IPs IBB Camp Coordination and Camp Al Mahwit IOM IPs Sana'a Management Al Mahwit IOM DHAMAR Sana'a IPs Cash Transfers for Food Al IPs IPs Economic Recovery and Market Systems Hudaydah IPs IPs Food Voucher Program RAYMAH IPs Dhamar Health Raymah Al Mukalla IPs Shabwah Ataq Dhamar COUNTRYWIDE Humanitarian Coordination Al Bayda’ and Information Management IP Local, Regional, and International Ibb AD DALI’ Procurement TA’IZZ Al Bayda’ IOM Ibb ABYAN IOM Al BAYDA’ Logistics Support and Relief Ad Dali' OCHA Commodities IOM IOM IP Ta’izz Ad Dali’ Abyan IPs WHO Multipurpose Cash Assistance Ta’izz IPs IPs UNHAS Nutrition Lahij IPs LAHIJ Zinjubar UNICEF Protection IPs IPs WFP Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food IOM Al-Houta ADEN FAO Refugee and Migrant Assistance IPs Aden IOM UNICEF Risk Management Policy and Practice Shelter and Settlements IPs WFP SOCOTRA DJIBOUTI, ETHIOPIA, U.S. -

Eiectronic Integrated Disease Early Warning and Response System Volume 07,Lssue47,Epi Week 47,(18-24 November,2019)

Ministary Of Public Health Papulation Epidemiological Bulletin Primary Heath Care Sector Weekly DG for Diseases Control & Surveillance Eiectronic Integrated Disease Early Warning and Response System Volume 07,lssue47,Epi week 47,(18-24 November,2019) Highlights eDEWS Reporting Rates vs Consultations in Govemorates,Epi Weeks 1-47,2019 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 95 97 97 % 96 96 96 96 96 96 96 96 96 96 96 96 96 % 96 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 94 94 94 94 94 94 94 100% % 450000 93 92 96 93 90% 93 400000 •During week no.47,2019, %95(1991/1883) health facilites from 23 80% 350000 70% 300000 Governorates provided valid surveillance data. 60% 250000 50% 200000 Percentage 40% 150000 Consulttaions 30% 20% 100000 10% 50000 •The total number of consultation reported during the week in 23 0% 0 Wk 1 Wk 4 Wk 7 Wk Wk Wk 2 Wk 3 Wk 5 Wk 6 Wk 8 Wk 9 Wk 20 Wk 23 Wk 26 Wk 29 Wk 32 Wk 35 Wk 38 Wk 41 Wk 44 Wk 11 Wk 12 Wk 13 Wk 14 Wk 15 Wk 16 Wk 17 Wk 18 Wk 19 Wk 21 Wk 22 Wk 24 Wk 25 Wk 27 Wk 28 Wk 30 Wk 31 Wk 33 Wk 34 Wk 36 Wk 37 Wk 39 Wk 40 Wk 42 Wk 43 Wk 45 Wk 46 Wk 47 Governorates was 397352 compared to 387266 the previous reporting week Wk 10 47. Acute respiratory tract infections lower Respiratory Infections (LRTI), Upper Reporting Rate Consultations Respiratory Infections (URTI), Other acute diarrhea (OAD) and Malaria (Mal) Distribution of Reporting Rates by Governoraes (Epi-Week 47,2019) % % % % % % % % were the leading cause of morbidity this week. -

Struggle for Citizenship.Indd

From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen CRU Report From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice FROM THE STRUGGLE FOR CITIZENSHIP TO THE FRAGMENTATION OF JUSTICE Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen Conflict Research Unit, The Clingendael Institute February 2014 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Clingendael Institute P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/ Table of Contents Executive summary 7 Acknowledgements 11 Abbreviations 13 1 Introduction 14 2 Selective centralisation of the state: Commerce and security through networked rule 16 Enablers: Tribes, remittances, oil and civil war 17 Tools: Violence, business and religion 21 The year 2011 and the National Dialogue Conference 26 The state of justice in 1990 and 2013 28 3 Trend 1: The ‘instrumentalisation’ of state-based justice 31 Key strategies in the instrumentalisation of justice 33 Consequences of politicisation and instrumentalisation 34 4 Trend 2: The weakening of tribal customary law 38 Functions and characteristics of tribal law 40 Key factors that have weakened tribal law 42 Consequences of weakened tribal law 44 Points of connection -

Whether Civil War Happened During the Arab

國立政治大學外交學系 Department of Diplomacy, National Chengchi University 碩士論文 Master Thesis 治 政 大 立 學 論阿拉伯之春期間內戰是否發生:以阿爾及利亞 國 和利比亞為例 ‧ ‧ N a y Whether Civil War Happened Duringt the Arab t i i s o r Spring: Exemplifiedn by Algeria eand Libya a i v l C n heng chi U 指導教授:劉長政 Advisor: Liu, Chang-Cheng 作者:楊邵帆 Author: Yang, Shao-Fan 日期:民國 103 年 6 月 16 日 Date: June 16, 2014 Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... iv Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................... vi Abstracts ............................................................................................................................ viii 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Research Goals .................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Literature Review ............................................................................................................ 3 1.2.1. Arab Spring in General ......................................................................................................... 3 1.2.2. Situation in Different Country before or During the Arab Spring ...................... 7 1.2.3. Theories for the Onset of Civil War............................治 .................................................. 19 政 大 1.3. Research Design