Inner-City Sydney Aboriginal Homeless Research Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The City of Sydney

The City of Sydney City Planning, Urban Design and Planning, CVUT. Seminar Work by Phoebe Ford. LOCATION The City of Sydney, by M.S. Hill, 1888. State Library of New South Wales. Regional Relations The New South Wales Government conceptualises Sydney as ‘a city of cities’ comprising: The Central Business District (CBD) which is within the City of Sydney Local Government Area (LGA), the topic of my presentation, and North Sydney, which make up ‘Global Sydney’, and the regional cities of Parramatta, Liverpool and Penrith. This planning concept applies the Marchetti principle which aims to create a fair and efficient city which offers jobs closer to homes, less travel time and less reliance on a single CBD to generate employment. The concept is that cities should be supported by major and specialized centres which concentrate housing, commercial activity and local services within a transport and economic network. Walking catchment centres along rail and public transport corridors ‘One-hour Cities’ of the Greater Metropolitan Region of Sydney Sydney’s sub-regions and local government areas Inner Sydney Regional Context City of Sydney Local Government Area Importance Within Broader Context of the Settlements Network • Over the last 20 years, ‘the Global Economic Corridor’ - the concentration of jobs and infrastructure from Macquarie Park through Chatswood, St Leonards, North Sydney and the CBD to Sydney Airport and Port Botany- has emerged as a feature of Sydney and Australia's economy. • The corridor has been built on the benefits that businesses involved in areas such as finance, legal services, information technology, engineering and marketing have derived from being near to each other and to transport infrastructure such as the airport. -

The Builders Labourers' Federation

Making Change Happen Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cook, Kevin, author. Title: Making change happen : black & white activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, union & liberation politics / Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall. ISBN: 9781921666728 (paperback) 9781921666742 (ebook) Subjects: Social change--Australia. Political activists--Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--20th century. Australia--Social conditions--20th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Goodall, Heather, author. Dewey Number: 303.484 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover images: Kevin Cook, 1981, by Penny Tweedie (attached) Courtesy of Wildlife agency. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History RSSS and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National -

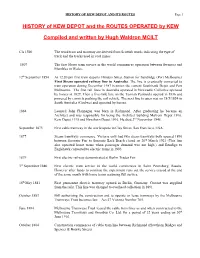

__History of Kew Depot and It's Routes

HISTORY OF KEW DEPOT AND ITS ROUTES Page 1 HISTORY of KEW DEPOT and the ROUTES OPERATED by KEW Compiled and written by Hugh Waldron MCILT CA 1500 The word tram and tramway are derived from Scottish words indicating the type of truck and the tracks used in coal mines. 1807 The first Horse tram service in the world commences operation between Swansea and Mumbles in Wales. 12th September 1854 At 12.20 pm first train departs Flinders Street Station for Sandridge (Port Melbourne) First Steam operated railway line in Australia. The line is eventually converted to tram operation during December 1987 between the current Southbank Depot and Port Melbourne. The first rail lines in Australia operated in Newcastle Collieries operated by horses in 1829. Then a five-mile line on the Tasman Peninsula opened in 1836 and powered by convicts pushing the rail vehicle. The next line to open was on 18/5/1854 in South Australia (Goolwa) and operated by horses. 1864 Leonard John Flannagan was born in Richmond. After graduating he became an Architect and was responsible for being the Architect building Malvern Depot 1910, Kew Depot 1915 and Hawthorn Depot 1916. He died 2nd November 1945. September 1873 First cable tramway in the world opens in Clay Street, San Francisco, USA. 1877 Steam tramways commence. Victoria only had two steam tramways both opened 1890 between Sorrento Pier to Sorrento Back Beach closed on 20th March 1921 (This line also operated horse trams when passenger demand was not high.) and Bendigo to Eaglehawk converted to electric trams in 1903. -

State Transit North Shore & West

Trains to Hornsby, West Central Coast and Newcastle Beecroft Pennant ah St Beecroft ve Hann A Railway Station a B av e Hills t e ra c Rd r Beecroft Station O d peland o R Co ft ls R il d H Hanover Ave 553 t A e ik S en Rd Legend v t m Marsfield A Garigal n a la a kh 295 o National n ir Ko n K e Park Lindfield d 553 P Cheltenham 136 Range R 292 293 Police Station To Manly torway Railway Station North Epping Norfolk Rd Malton Rd Ch East Killara Garden Village Forestville M2 Mo urc hil 553 Boundary Rd Hospital l Rd 137 553 d E 551 To Bantry Bay aton R e Rd Cheltenham ast 206 E tmor Oakes Road Rd co Wes Farm Grayson Rd Newton tSt Garigal M2 Bus Station Murray e Rd (House with No Steps) Shopping Centres Sp National O r 207 Larra C Epping Station (East) W ing re a a da Park s k terloo Rd le 160X Westfield e Rd To Mona Vale s Grig Devon St Metro Station g R M Av 208 d 291 295 North Rocks i 288 290 e d d R See Northern Mill Dr s o M2 Motorway E n P n For more details Railway Station a o d Region Guide. Rd Norfolk Rd s y Barclay Road m e Bedford Rd t r y Far R er T R rra n Gl 553 Mu s Rd d n n k n Busaco Rd c L M2 Bus Station Ro A to h o r Nort a on Macquarie te g d a n r a n t u T e R n B i li v S t Dorset St a Light Rail Stop l l f cester A Ba e lavera Rd e o r h y clay P Epping Station (West) R t e n Lindfield r R Killara W n a r d Yo r d d d a g g Waterloo Rd bus routes see v d e e Soldiers s R 549 h A d Garden Village n s i A P m r ea R llia a K l r v i k ie e Oxford StSurrey St Memorial r W z 546 P e b e J Educational Institutions l a Ray -

NSW Police Gazette 1886

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently The resolution of this sampler has been reduced from the original on CD to keep the file smaller for download. New South Wales Police Gazette 1886 Ref. AU2103-1886 ISBN: 978 1 921371 40 0 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by Griffith University www.griffith.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

2040 Masterplan

Historical Map 1917 SCEGGS Darlinghurst, 215 Forbes Street, Darlinghurst NSW 2010 ¯ 1000m Legend Site Boundary Buffer 1000m Scale: Data Sources: Australia 1:63360, Sheet 423, Coordinate System: Date: 10 August 2018 GDA 1994 MGA Zone 56 0 200 400 800 Sydney, New South Wales. Meters Prepared by Commonwealth Section Imperial General Staff Lotsearch Pty Ltd ABN 89 600 168 018 126 Topographic Features SCEGGS Darlinghurst, 215 Forbes Street, Darlinghurst, NSW 2010 SYDNEY HARBOUR SYDNEY HARBOUR BRIDGE STREET E T L Y E C A E R SYDNEY I W R C L D HARBOUR T ¯ I Y A A S T R O I R P C YL I S W L E D I L E I R H A S P H C U T UN A Q TER ST H C R REET IL A E GEORGE STREET L M D E EX S 1000m T A P 617744 RE R O S M SW R 617190 AY MARTIN PLACE L Y SYDNEY A 617728 A POTTS POINT 617776 617764 T 617738 HARBOUR I W SESQUICENTENARY P 617668 D S A SQUARE B YORK STREET 617787 617575 O E O 617732 A I H R K 617650 S L ING STR 617576 T C F 617720 EET 617785 E O R L R W A 617789 N PER W H 617949 Y 617239 A R S R QUEENS SQUARE A U D 617753 617803 I B A 617798 L U W 617226 V 617790 617628 R E A B 617721 N 617527 T U N Y S E S E O 617779 T 617781 E R R M MACLEAY STREET AR R A T 617760 617780 Y T I H 617802 L S 617941 617669 S W S 617743 ELIZABETH BAY 617712 R G 617200 H A 617520 617697 O N O 617731 B Y A H D I A 617206 120117127 T Y R L R 617815 617224 E O T AD E 617750 B 617566 617503 C W E A S A E 120121036 T O 617958 HEDR IZ N A R 617959 617227 L STR D EL E 617463 E T C 617814 ET 617209 D SYDNEY ROSS 617811 617722 R C BROUGHAM STREET S ITY A HARBOUR TUNN L 617796 -

Parramatta River Walk Brochure

Parramatta Ryde Bridge - Final_Layout 1 30/06/11 9:34 PM Page 1 PL DI r ELIZA ack BBQ a Vet E - Pav W PL CORONET C -BETH ATSON Play NORTH R 4 5 PL IAM 1 A NORTH A L H L Br Qu CR AV I John Curtin Res Northmead Northmead Res R G AV W DORSET R T PARRAMATTA E D Bowl Cl To Bidjigal R PARRAMATTA O Moxham Guides 3 2 R AR O P WALTE Hunts D ReservePL N S Park M A 2151 Creek O EDITH RE C CR N The E Quarry Scouts ANDERSON RD PL PYE M AMELOT SYDNEY HARBOUR Madeline RD AV C THIRLMER RD SCUMBR Hake M Av Res K PL Trk S The BYRON A Harris ST R LEVEN IAN Park E AV R PL E Moxhams IN A Craft Forrest Hous L P Meander E L G Centre Cottage Play M PL RD D S RD I L Bishop Barker Water A B Play A CAPRERA House M RD AV Dragon t P L Basketba es ST LENNOX Doyle Cottage Wk O O Whitehaven PL PL THE EH N A D D T A Res CARRIAGE I a a V E HARTLAND AV O RE PYE H Charl 4 Herber r Fire 5 Waddy House W Br W THA li n 7 6 RYRIE M n TRAFALGAR R n R A g WAY Trail Doyle I a MOXHAMS RD O AV Mills North Rocks Parramatta y y ALLAMBIE CAPRER Grounds W.S. Friend r M - Uniting R Roc Creek i r 1 Ctr Sports r Pre School 2 LA k Lea 3 a Nurs NORTH The r Baker Ctr u MOI Home u DR Res ST Convict House WADE M Untg ORP Northmead KLEIN Northmead Road t Play SPEER ROCKS i Massie Baker River Walk m Rocky Field Pub. -

Community Land Plan of Management 2014

Community Land Plan of Management 2014 Adopted by Council 28 July 2014 Disclaimer Parramatta City Council has made a reasonable effort to ensure that the information contained in this document was current and accurate at the time the document was created and last modified. The Council make no guarantees of any kind, and no legal contract between the Council and any other person or entity is to be inferred from the use of information in this document. The Council accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of information. No user should rely on the information, but instead check for confirmation with the originating or authorising body. Open Space & Natural Resources Parramatta City Council PO Box 32, PARRAMATTA NSW 2150 Phone: 02 9806 5050 Fax: 02 9806 5906 Email: [email protected] Website: www.parracity.nsw.gov.au COMMUNITY LAND PLAN OF MANAGEMENT 2014 Page 2 “Parramatta will be the driving force and heart of Australia’s most significant economic region; a vibrant home for diverse communities and a centre of excellence in research, education and enterprise.” (Parramatta Twenty38 Vision) COMMUNITY LAND PLAN OF MANAGEMENT 2014 Page 3 CONTENTS 1 Introduction .................................................................. 6 1.1 Background .......................................................................................... 6 1.2 What is a Plan of Management? .......................................................... 6 1.3 Need for this Plan of Management ...................................................... -

George Street 2020 – a Public Domain Activation Strategy

Sydney2030/Green/Global/Connected George Street 2020 A Public Domain Activation Strategy Adopted 10 August 2015 George Street 2020 A Public Domain Activation Strategy 01/ Revitalising George Street 1 Our vision for George Street The Concept Design Policy Framework Related City strategies George Street past and present 02/ The George Street Public Domain 11 Activation principles Organising principles Fixed elements Temporary elements 03/ Building use 35 Fine grain Public rest rooms and storage 04/ Building Elements 45 Signs Awnings Building materials and finish quality 05/ Public domain activation plans 51 06/ Ground floor frontage analysis 57 George Street 2020 - A Public Domain Activation Strategy Revitalising George Street 1.1 Our vision for George Street Building uses, particularly those associated with the street level, help activate the street by including public amenities By 2020 George Street will be transformed into and a fine grain, diverse offering of goods, services and Sydney’s new civic spine as part of the CBD light rail attractions. project. It will be a high quality pedestrian boulevard, linking Sydney’s future squares and key public Building elements including awnings, signage and spaces. materiality contribute to the pedestrian experience of George Street. This transformation is a unique opportunity for the City to maximise people’s enjoyment of the street, add vibrancy This strategy identifies principles and opportunities relating to the area and support retail and the local economy. This to these elements, and makes recommendations for the strategy plans for elements in the public domain as well design of George Street as well as policy and projects to as building edges and building uses to contribute to the contribute to the ongoing use and experience of the street. -

Rain Drives Foraging Decisions of an Urban Exploiter Matthew Hc Ard University of Wollongong, [email protected]

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 2018 Rain drives foraging decisions of an urban exploiter Matthew hC ard University of Wollongong, [email protected] Kris French University of Wollongong, [email protected] John Martin Trustee for Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, [email protected] Richard E. Major Australian Museum, [email protected] Publication Details Chard, M., French, K., Martin, J. & Major, R. E. (2018). Rain drives foraging decisions of an urban exploiter. PLoS One, 13 (4), e0194484-1-e0194484-14. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Rain drives foraging decisions of an urban exploiter Abstract Foraging decisions tend to drive individuals toward maximising energetic gains within a patchy environment. This study aims to determine the extent to which rainfall, and associated changes in food availability, can explain foraging decisions within a patchy urbanised landscape, using the Australian white ibis as a model species. Ibis density, food consumption rates and food abundance (both natural and anthropogenic) were recorded during dry and wet weather within urban parks in Sydney, Australia. Rainfall influenced ibis density in these urban parks. Of the four parks assessed, the site with the highest level of anthropogenic food and the lowest abundance of natural food (earthworms), irrespective of weather, was observed to have three times the density of ibis. Rainfall significantly increased the rate of earthworm consumption as well as their relative availability in all sites. -

The History of Moore Park, Sydney

The history of Moore Park, Sydney John W. Ross Cover photographs: Clockwise from top: Sunday cricket and Rotunda Moore Park Zoological Gardens (image from Sydney Living Museums) Kippax Lake Sydney Morning Herald, 30 August, 1869 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Timeline................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sydney Common ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Busby’s Bore ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Moore Park General Cemetery ............................................................................................................. 11 Victoria Barracks ................................................................................................................................... 13 Randwick and Moore Park Toll Houses ................................................................................................ 17 Paddington Rifle Range ......................................................................................................................... 21 Sydney Cricket Ground ........................................................................................................................ -

NSW HRSI NEWS January 2016

NSW HRSI NEWSLETTER Issue 6 HRSI NSW HRSI NEWS January 2016 A view of the Lithgow old locomotive roundhouse in 1976 (Jim Lippitts collection) NSW HERITAGE RAILWAY STATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE NEWS ISSUE N.6 WELCOME to the sixth newsletter from local levels and to be Newsletter index of NSWHRSI. The objective of this continuous. It is difficult for some newsletter is to inform, educate and external volunteers to commit time WELCOME / MAIN NEWS 1 provide insights about the latest and funds to help out, especially if STATION MASTERS HOUSES ACROSS updates, plans and heritage news long distances is involved in travels NSW - A REVIEW 2 relating to Heritage Railway to project. Stations and Infrastructure (HRSI) Phil Buckley, NSW HRSI Editor CULCAIRN TO COROWA RAILWAY across NSW. The news in this letter BRANCH LINE REVIEW 6 is separated into 4 core NSW Copyright © 2014 - 2016 NSWHRSI . regions – Northern, Western and All photos and information remains ST JAMES STATION SYDNEY: HIDDEN Southern NSW and Sydney property of HRSI / Phil Buckley unless TUNNELS 22 stated to our various contributors / MAIN NEWS original photographers or donors. COMMUNITY REUSE OF ABANDONED RAILWAY STATIONS – PART 2 - Late 2015 has seen the resurgence Credits/Contributors this issue – Bob WESTERN NSW 25 of various plans to reopen stations Scrymgeour – “The Culcairn to Corowa and railway lines across NSW. Some Railway”, Mark Zanker, Peter NORTHERN NSW 26 station plans are not publicly Sweetten, Chris Stratton, Steve Bucton, Adrian Compton, Andrew released yet but are expecting to be WESTERN NSW 30 made in early 2016. The interest in Lawson, Allan Hunt, Gordon Ross, Craig Thistlethwaite, Lindsay maintaining country NSW rail SOUTHERN NSW 32 Richmond, Peter Burr, Brett Leslie, heritage links is strong for some Greg Finster, Warren Banfield, Robert communities and not as strong for Paterson, Jim Lippitts and Douglas SYDNEY REGION 36 others.