The Iranian Press and Modernization Under the Qajars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manifestation of Modernity in Iranian Public Squares: Baharestan Square (1826–1978)

Asma Mehan, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 411–420 MANIFESTATION OF MODERNITY IN IRANIAN PUBLIC SQUARES: BAHARESTAN SQUARE (1826–1978) ASMA MEHAN Department of Architecture and Design, Politecnico Di Torino, Italy. ABSTRACT The concept of public square has changed significantly in Iran in recent centuries. This research inves- tigated how modernity is manifested in the public squares of Tehran. In this regard, Tehran has been chosen as the main concern, while in its short history as the capital of Iran, the city has been critically transformed: first because of constant urban development during the Qajar Dynasty and then due to its rapid growth during the late Pahavi era and second because of the culture of rapid renovation and reconstruction in contemporary public spaces. Considering these facts, the urban transformation of Baharestan Square as one of the most influencing public squares of Tehran in the recent century leads us to understand the process of Iranian modernization, which is totally different from common patterns of western modernity. Analysing the historical changes of Baharestan Square based on manuscripts, western travellers’ diaries, historical images and maps, from its formation till the Islamic Revolution (1978), shows how the traditional elements of the square as well as its form and function have been totally transformed. Analysing the spatial qualities of Baharestan Square clarifies that its special loca- tion near the first Iranian Parliament building, Sepahsalar Mosque and Negarestan Garden represents it as the first modern focal point in Iranian’s political and social life. Keywords: Baharestan Square, Iranian modernity, public square, Tehran. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Interview with Bahman Jalali1

11 Interview with Bahman Jalali1 By Catherine David2 Catherine David: Among all the Muslim countries, it seems that it was in Iran where photography was first developed immediately after its invention – and was most inventive. Bahman Jalali: Yes, it arrived in Iran just eight years after its invention. Invention is one thing, what about collecting? When did collecting photographs beyond family albums begin in Iran? When did gathering, studying and curating for archives and museum exhibitions begin? When did these images gain value? And when do the first photography collections date back to? The problem in Iran is that every time a new regime is established after any political change or revolution – and it has been this way since the emperor Cyrus – it has always tried to destroy any evidence of previous rulers. The paintings in Esfahan at Chehel Sotoon3 (Forty Pillars) have five or six layers on top of each other, each person painting their own version on top of the last. In Iran, there is outrage at the previous system. Photography grew during the Qajar era until Ahmad Shah Qajar,4 and then Reza Shah5 of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah held a grudge against the Qajars and so during the Pahlavi reign anything from the Qajar era was forbidden. It is said that Reza Shah trampled over fifteen thousand glass [photographic] plates in one day at the Golestan Palace,6 shattering them all. Before the 1979 revolution, there was only one book in print by Badri Atabai, with a few photographs from the Qajar era. Every other photography book has been printed since the revolution, including the late Dr Zoka’s7 book, the Afshar book, and Semsar’s book, all printed after the revolution8. -

Curriculum Vitae (Cv)

IV. Appendices Time-Based CURRICULUM VITAE (CV) Position Title and No. Director, Planning Division, Urmia Lake Restoration Program (ULRP) Name of Expert: Ali Hajimoradi Date of Birth: 21.07.1986 Country of Citizenship/Residence Iran/ Tehran Education: 1. PhD student, subject: Water and Hydraulic Structure, Civil Engineering School, Tabriz University, Dissertation title: Uncertainty Analysis in Irrigation and Drainage Network of Urmia Lake Basin with Fuzzy Logic 2. MSc, Amir Kabir University of Technology, Water Engineering, 2013 3. BSc., Isfahan Technology of University, Civil Engineering, 2009, 4. Diploma, High School of Isfahan Technology of University, Mathematics and Physics, 2004, Employment record relevant to the assignment: Period Employing organization and your title/position. Country Summary of activities Contact information for references performed relevant to the Assignment Urmia Lake Restoration Program (ULRP) Iran Task leader of 2015 - Volume metric present -Director, Planning Division water distribution in Mahabad Masoud Tajrishy, Director of Planning and Irrigation and Resource Mobilization, ULRP Drainage network Tel: +989121448230 Team lead of Email: [email protected] Hassanloo Dam Water Allocation to farmers while cropping pattern changed Project coordinator of Dust control in west and south part of Urmila Lake, Member of Technical Committee on Herbs value IV. Appendices Time-Based chain Agriculture and Water National Research Tehran, 2018 Center Iran -Trainer, course title: Lessons learned from Australia Water -

Republic of Uzbekistan QUICK FACTS UZBEKISTAN

Republic of Uzbekistan QUICK FACTS UZBEKISTAN ............................................................................ The telecommunications market of Uzbekistan is in the Land Area: 425, 400 sq km process of saturation and is one of the fastest growing Population: 28.2 million sectors of the economy. Uzbekistan has the highest rate GNI per capita, PPP $3,110 (WB, 2010) of growth in the number of mobile subscribers in the CIS. The growth rate of revenues from mobile services TLD: .uz lags behind the pace of growth in the number of mobile Fixed Telephones: 1.9 million (2010) subscribers. There were 24.3 million mobile subscribers GSM Telephones: 24.3 million (2011) to the end of 2011.83 Fixed Broadband: 0.15 million (2010) Internet Users: 8.8 million (2012) TELECOMMUNICATIONS MARKET Indicator80 Measurement Value Computers Per 100 n/a Kazakstan Internet Users Per 100 31.2 Fixed Lines Per 100 6.6 Internet Broadband Per 100 0.3 Uzbekistan Kyrgyzstan Mobile Subscriptions Per 100 84.0 Mobile Broadband Per 100 19.9 (est) Turkmenistan Tajikistan International Bandwidth Per 100 17.2 kb Iran There have been no changes in number of operators Afghanistan in the last 3 years: “MTS” brand from “Uzdunrobita” (established June 1991) GSM/UMTS; “Beeline” brand from “Unitel” (established in April 1996) GSM/UMTS; In August 2011, all mobile operators in Uzbekistan 84 “Ucell” brand from “COSCOM” (established in April suspended internet and messaging services for the 1996) GSM/UMTS; “Perfectum Mobile” brand from duration of university entrance exams in an attempt to “Rubicon Wireless Communication” (established in prevent cheating. Five national mobile operators shut November 1996) CDMA 2001X; “UzMoble” brand from down mobile internet, text, and picture messaging JSC “Uzbektelecom” (established in August 2000) for four hours from 9 am local time, citing “urgent CDMA-450. -

Iran 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

IRAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution defines the country as an Islamic republic and specifies Twelver Ja’afari Shia Islam as the official state religion. It states all laws and regulations must be based on “Islamic criteria” and an official interpretation of sharia. The constitution states citizens shall enjoy human, political, economic, and other rights, “in conformity with Islamic criteria.” The penal code specifies the death sentence for proselytizing and attempts by non-Muslims to convert Muslims, as well as for moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and sabb al-nabi (“insulting the Prophet”). According to the penal code, the application of the death penalty varies depending on the religion of both the perpetrator and the victim. The law prohibits Muslim citizens from changing or renouncing their religious beliefs. The constitution also stipulates five non-Ja’afari Islamic schools shall be “accorded full respect” and official status in matters of religious education and certain personal affairs. The constitution states Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians, excluding converts from Islam, are the only recognized religious minorities permitted to worship and form religious societies “within the limits of the law.” The government continued to execute individuals on charges of “enmity against God,” including two Sunni Ahwazi Arab minority prisoners at Fajr Prison on August 4. Human rights nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) continued to report the disproportionately large number of executions of Sunni prisoners, particularly Kurds, Baluchis, and Arabs. Human rights groups raised concerns regarding the use of torture, beatings in custody, forced confessions, poor prison conditions, and denials of access to legal counsel. -

Modernizing the Public Space: Gender Identities

MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN A DISSERTATION IN Geosciences and Sociology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by NAZGOL BAGHERI Bachelor of Architecture, 2004 Bachelor of Computer Science, 2006 Master of Urban Design, 2007 Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran Kansas City, Missouri 2013 © 2013 NAZGOL BAGHERI ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN Nazgol Bagheri, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri - Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, surprisingly, the presence of Iranian women in public spaces dramatically increased. Despite this recent change in women’s presence in public spaces, Iranian women, like in many other Muslim-majority societies in the Middle East, are still invisible in Western scholarship, not because of their hijabs but because of the political difficulties of doing field research in Iran. This dissertation serves as a timely contribution to the limited post-revolutionary ethnographic studies on Iranian women. The goal, here, is not to challenge the mainly Western critics of modern and often privatized public spaces, but instead, is to enrich the existing theories through including experiences of a more diverse group. Focusing on the women’s experience, preferences, and use of public spaces in Tehran through participant observation and interviews, photography, architectural sketching as well as GIS spatial analysis, I have painted a picture of the complicated relationship between the architecture styles, the gendering of spatial boundaries, and the contingent nature of public spaces that goes beyond the simple dichotomy of female- male, private-public, and modern-traditional. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 4 2012’’

In the House of Representatives, U. S., August 1, 2012. Resolved, That the House agree to the amendment of the Senate to the bill (H.R. 1905) entitled ‘‘An Act to strengthen Iran sanctions laws for the purpose of compelling Iran to abandon its pursuit of nuclear weapons and other threatening activities, and for other purposes.’’, with the following HOUSE AMENDMENT TO SENATE AMENDMENT: In lieu of the matter proposed to be inserted by the amendment of the Senate, insert the following: 1 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. 2 (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the 3 ‘‘Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 4 2012’’. 5 (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for 6 this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. Definitions. TITLE I—EXPANSION OF MULTILATERAL SANCTIONS REGIME WITH RESPECT TO IRAN Sec. 101. Sense of Congress on enforcement of multilateral sanctions regime and expansion and implementation of sanctions laws. Sec. 102. Diplomatic efforts to expand multilateral sanctions regime. TITLE II—EXPANSION OF SANCTIONS RELATING TO THE ENERGY SECTOR OF IRAN AND PROLIFERATION OF WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION BY IRAN Subtitle A—Expansion of the Iran Sanctions Act of 1996 Sec. 201. Expansion of sanctions with respect to the energy sector of Iran. 2 Sec. 202. Imposition of sanctions with respect to transportation of crude oil from Iran and evasion of sanctions by shipping companies. Sec. 203. Expansion of sanctions with respect to development by Iran of weapons of mass destruction. Sec. -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE a Study on the Relationship Between Temperature

Bulletin of Environment, Pharmacology and Life Sciences Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci., Vol 3 [12] November 2014: 42-45 ©2014 Academy for Environment and Life Sciences, India Online ISSN 2277-1808 Journal’s URL:http://www.bepls.com CODEN: BEPLAD Global Impact Factor 0.533 Universal Impact Factor 0.9804 ORIGINAL ARTICLE A study on the relationship between temperature and height in Ardabil province, according to the meteorological data Bahman Bahari Bighdilu Department of Agriculture, Pars Abad Moghan Branch, Islamic Azad University, pars Abad Moghan, Iran Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT the relationship between temperature and height was investigated Based on the review of one of the most important climatic parameters (temperature) in order to provide scientific solutions to meet the social needs and careful planning in the region in the field of agriculture. There was a significant relationship on the basis of Laps Rate phenomenon, so that the differences between heating and cooling processes of 70 degrees Celsius and the height difference of 1500 meters in the province show this important issue. Keywords: temperature, according, meteorological data Received 10.09.2014 Revised 09.10.2014 Accepted 02.11. 2014 INTRODUCTION Location, range and area This region with the area of 17,867 square kilometers is located at the north of Iran plateau between the coordinates of '45 and ‘37 to '42 and '39 North latitude and '55 and 48 to '3 and 47 east longitudes from the Greenwich meridian. Based on the assessment studies of Land resources in this area (Ardabil Province) a total of 7 major types and one type of mixed lands and 32 units of land have been identified. -

Water and Irrigation System in Qajar Period

Science Arena Publications Specialty Journal of Humanities and Cultural Science ISSN: 2520-3274 Available online at www.sciarena.com 2019, Vol, 4 (2): 43-49 Water and Irrigation System in Qajar Period Sayyed Sasan Mousavi Ghasemi1, Abbas Ghadimi Gheydari2* 1Master of the History of Islamic Iran, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran. 2Associate Professor of History Group, Faculty of Law and Social Sciences, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran. *Corresponding Author Abstract: Qajar dynasty, which came to power in Iran in early years of the 19th century (end of the 12th century AH) inherited a country that, over the previous century, its economic power had been severely degraded due to many domestic problems and chaos as well as foreign wars and aggressions. Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, through about twenty years of persistent efforts, could restore political cohesion and integrity to the country. As economy of Iran is considered an agricultural economy, this means that in this system, land ownership and irrigation system are among the important affairs. It can be said that from the 1800s to the last years of Qajar period, agriculture has used the same traditional system of ownership and rural relations have remained unchanged. The only difference seen in this regard is formation of cities and presence of villagers living in the city. In Qajar period, especially in the nineteenth century, the country had not yet entered into capitalist relations, and its monetary economy had not grown much, and the prevailing economy, which mainly provided internal needs of the country, was traditional agriculture. It is very difficult to draw an approximate picture of Iran’s agriculture in the nineteenth century or to show general evolutions of the country that have led to its development, because on one hand, the government has left nothing but some minor investigations of conditions of villages and, in practice, there is nothing about statistics but tax papers. -

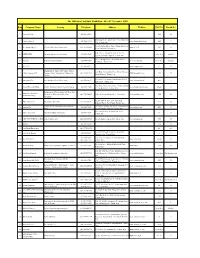

Row Company Name Activity Telephone Address Website Hall No Booth No

The 10th Auto Parts Int,l. Exhibition - 16 to 19 November 2015 Row Company Name Activity Telephone Address WebSite Hall No Booth No 1 Abarashi Group (021)36466786 31B 38 D46 Golgasht St., Golzar Ave, Parand Industrial 2 Abzar Andisheh (021)56419014 www.abzarandisheh.com 40B 7 City, Tehran- Iran No.120, Kalhor Blvd, Shahre Ghods, 20th km of 3 Ace Engineering Co Electrical Auto Part Manufacturer (021)46884888-9 www.ACE.IR 40B 16 Karaj Old Road, Tehran, Iran Unit 2, No. 4, Koopayeh Alley, Before the 4 ADIB IMENi Garment industry and advertising (021)55380846 Open Area South 31 Qazvin Sq, South Kargar St, Tehran, Iran No. 17, Dastgheib Ave, West Shahed Blvd., 5 Agradad Industrial Automatic Door (021)44588684 www.agradad.com Open Area South 31 Tehransar, Tehran, Iran 6 AL.TECH. (021)26760992 www.dinapart.com 6 38 Manufactur of Types of Steel Parts by hot Sarir Bldg., Peykanshahr Exit,15th km Tehran- 7 Alborz Forging IND forging method, Auto Gearbox, Suspension (021)44784191-5 www.forgealborz.com 40B 29 Karaj Highway, Tehran- Iran Chassis No. 18 & 19, Next to the Gas Station, West 15 8 Aluminium Faz Car Aluminium Parts (Die Casting) (021)55690137 www.aluminiumfaz.ir 40A 3 Khordad St., Tehran, Iran First Floor, No.7, Zahiroleslam Alley, Iranshahr 9 Alvand Electronic Dana Vehicle Tracking, kinds of electronic boards (021)88313640 www.alvandelectronic.com 20-22 16 St., Taleghani Ave., Tehran- Iran Production of different kind of oil filters, Fuel Aman Filter Industrial 10 filters & Air filters for light & heavy (021)77167003-5 Unit 6, 3rd Floor, Piroozi Ave, Tehran, Iran www.amanfilter.com 31B 28 Production Group automobile No.207, 208- F, Sarv 24 St, Nasirabad 11 Aman Ghate Kar Automobile spare parts (021)56390795 20-22 20 Industrial Town, Saveh Road, Tehran, Iran Manufacturing Auto suspension & steering 1st Eastern 20 Meter St., Tabriz Exhibition old 12 Amirnia Co.