EDO NSW Report Merits Review in Planning in NSW Foreword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and Professional Papers and Records Of

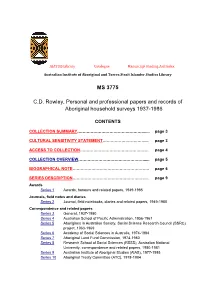

AIATSIS Library Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys 1937-1986 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY……………………………….…………...... page 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT…………………………..... page 3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION…………………………………………… page 4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW…………………………….……………..... page 5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………………………… page 6 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………... page 9 Awards Series 1 Awards, honours and related papers, 1949-1985 Journals, field notes and diaries Series 2 Journal, field notebooks, diaries and related papers, 1949-1980 Correspondence and related papers Series 3 General, 1937-1980 Series 4 Australian School of Pacific Administration, 1956-1961 Series 5 Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council (SSRC) project, 1963-1969 Series 6 Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, 1974-1984 Series 7 Aboriginal Land Fund Commission, 1974-1980 Series 8 Research School of Social Sciences (RSSS), Australian National University, correspondence and related papers, 1980-1981 Series 9 Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS), 1977-1985 Series 10 Aboriginal Treaty Committee (ATC), 1978-1984 MS 3775: C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys, 1937-1986 Series 11 Sundry, 1965-1981 Research project files Series 12 UNESCO Mission on Adult & Workers’ Education to S-E Asia, 1954-55 Series 13 Aborigines in -

Undermining Mabo the Shaming of Manning Clark on Your Way, Sister

Vol. 3 No. 8 October 1993 $5.00 Undermining Mabo On your way, sister Frank Brennan Pamela Foulkes The shaming of Manning Clark Trading in union futures Rosamund Dalziel! PauiRodan In Memoriam D.J.O'H One thirty. This is the time I saw you last Braving death with a grin in the stilled ward. Invaded and insulted, you stood fast, Ready to fight, or ford The cold black stream that rings us all about Like Ocean. Some of it got into your eyes That afternoon, smarting you not to doubt But to a new surprise At what sheer living brings-as once Yeats Braced in a question bewilderment, love and dying. As the flesh declines, the soul interrogates, Failing and stili trying. On a field of green, bright water in their shade, Wattles, fused and diffused by a molten star, Are pledging spring to Melbourne. Grief, allayed A little, asks how you are. 'Green is life's golden tree', said Goethe, and I hope that once again you're in a green Country, gold-fired now, taking your stand, A seer amidst the seen. Peter Steele In Memory of Dinny O'Hearn I Outcome, upshot, lifelong input, All roads leading to a dark Rome, We stumble forward, foot after foot: II You have taken your bat and gone home. Though you had your life up to pussy's bow, He disappeared in the full brilliance of winter, The innings wound up far too quick yellow sun unfailing, the voice of Kennett But the nature of knowledge, you came to know, utterly itself away on Shaftesbury A venue, Is itself the flowering of rhetoric. -

Annual Report 2004

2004 2005 ANNUAL REPORT MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS & SCIENCES INCORPORATING THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM & SYDNEY OBSERVATORY The Hon Bob Debus MP Attorney General, Minister for the Environment and Minister for the Arts Parliament House Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Minister On behalf of the Board of Trustees and in accordance with the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, we submit for presentation to Parliament the annual report of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences for the year ending 30 June 2005. Yours sincerely Dr Nicholas G Pappas Dr Anne Summers AO President Deputy President ISSN 0312-6013 © Trustees of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences 2005. Compiled by Mark Daly, MAAS. Design and production by designplat4m 02 9299 0429 Print run: 600. External costs: $14,320 Available at www.powerhousemuseum.com Contemporary photography by MAAS photography staff: Sotha Bourn, Geoff Friend, Marinco Kojdanovski, Jean-Francois Lanzarone and Sue Stafford (unless otherwise credited). Historical photos from Museum archives. Contents 02 President’s Foreword 03 Director’s Report 04 Mission and structure 05 Organisation chart 06 Progress against Strategic Plan 07 Goals 2005-06 08 Museum honours th 09 125 anniversary celebrations 10 Highlights of 2004-05 11 The Powerhouse Foundation 11 Evaluating our audiences, exhibitions and programs 12 Exhibition program 13 Travelling exhibitions 13 Public and education programs tm 15 SoundHouse and VectorLab 15 Sydney Observatory 16 Indigenous culture 16 Regional services 17 Migration -

City of Subiaco Attachments Development Services

CITY OF SUBIACO ATTACHMENTS DEVELOPMENT SERVICES COMMITTEE MEETING COUNCIL CHAMBERS 241 ROKEBY ROAD, SUBIACO TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 CONTENTS PAGE ITEM PAGE REPORT TITLE AND ATTACHMENT DESCRIPTION NO. NUMBER(S) D1 No. 136 (Lot 82) Gloster Street Subiaco – Extension to Term of 10 pages Development Approval for Single Storey Dwelling with Basement (7.2017.29) Attachment 1 – Development approval (8 March 2017) Attachment 2 – Location plan Attachment 3 – Site photographs D2 No. 2A (Lot 300) Cunningham Terrace, Daglish – Proposed Garage to 7 pages Single House – DA 7.2017.18 Attachment 1 – Plans for Determination Attachment 2 – Original development application plans (withdrawn) D3 No. 11 (Lot 35) Austin Street, Shenton Park – Two Storey Additions to 17 pages an Existing Two Storey Dwelling Attachment 1 – Development plans (8 February 2017) Attachment 2 – Development plans (22 May 2017) D4 Proposed Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area and Draft 25 pages Planning Policy 3.13 ‘Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area’ – adoption post advertising Attachment 1 – Map of proposed Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area Attachment 2 – Draft planning policy 3.13 ‘Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area’ – with tracked modifications Attachment 3 – Schedule of submissions including officer response D5 Proposed Daglish Workers’ Homes Board Heritage Area and Draft 6 pages Planning Policy 3.14 ‘Daglish Workers’ Homes Board Heritage Area’ – adoption post consultation Attachment 1 – Map of proposed Daglish Workers’ Homes Board Heritage Area Attachment -

Anzac Memorial Annual Report 2016 17.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 –17 The Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building Anzac Memorial Annual Report 2016–2017 Hyde Park South, Sydney NSW 2000 Locked Bag 53 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 T 02 9267 7668 E [email protected] © 2017 The Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building. This report was first published in October 2017. View or download this report from the Anzac Memorial website: www.anzacmemorial.nsw.gov.au Cover: Photograph by Rob Tuckwell Photography This page: Anzac Memorial cross sections by Bruce Dellit, Architect, 1930. Courtesy NSW Government Architect’s Office 2 | ANZAC MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2016 –17 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE TRUSTEES 5 CONTACT INFORMATION 7 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 8 The building of the Memorial Description of the Memorial Rededication of the Memorial ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND RESPONSIBILITIES 12 Organisational chart Governance Guardians of the Anzac Memorial Staffing ANZAC MEMORIAL CENTENARY PROJECT 18 Project and construction highlights The Anzac Memorial Centenary Project exhibition design The Anzac Memorial Centenary Project art commission 2016–17 OPERATIONS 24 Visitor engagement and participation Exhibitions and displays Public programs, events and ceremonies Other commemorative activities Fundraising Building management and maintenance THE COLLECTION 30 Significant acquisitions Documentation Collection management Conservation Research Training Public enquiries Senior Historian and Curator WEBSITE AND SOCIAL MEDIA 36 CONSUMER REVIEWS 37 Services improved/changed in response to suggestions GENERAL DISCLOSURES -

History and Planning in New South Wales

Newsletter of the Professional Historians’ Association (NSW) No. 238 September-October 2009 PHANFARE History and Planning in New South Wales Phanfare is the newsletter of the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc Published six times a year Free download from www.phansw.org.au Hardcopy annual subscription: $38.50 Articles, reviews, commentaries, letters and notices are welcome. Copy should be received by 6th of the first month of each issue (or telephone for late copy) Please email copy or supply on disk with hard copy attached. Contact Phanfare GPO Box 2437 Sydney 2001 Enquiries [email protected] Phanfare 2009-10 is produced by the following editorial collectives: Jan-Feb & July-Aug: Roslyn Burge, Mark Dunn, Shirley Fitzgerald, Lisa Murray Mar-Apr & Sept-Oct: Rosemary Broomham, Rosemary Kerr, Christa Ludlow, Terri McCormack May-June & Nov-Dec: Ruth Banfield, Cathy Dunn, Terry Kass, Katherine Knight, Carol Liston Disclaimer Except for official announcements the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc accepts no responsibility for expressions of opinion contained in this publication. The views expressed in articles, commentaries and letters are the personal views and opinions of the authors. Copyright of this publication: PHA (NSW) Inc Copyright of articles and commentaries: the respective authors ISSN 0816-3774 PHA (NSW) contacts see Directory at back of issue Contents Help Ban McDonalds Sandra Winkworth President’s Page 2 Proud of the unique culture and history of Lobbying is Legal 3 their suburb, Haberfield residents are currently fighting a proposal by the Balmain – a Den of Inquity 7 multinational fast-food chain McDonald's to build a drive-through outlet opposite the So much Sky. -

Place Management As a Core Role in Government by John Mant Abstract

Place Management As a Core Role in Government By John Mant Abstract Place Management can have a central role in government, particularly at the level of local government. For this to occur, fundamental organisational change is required. Instead of professionally based Divisions (or Departments) designed to deliver specialist outputs, the structure of government is designed around its core operating objectives – effectiveness, efficiency and transparency, or, Outcomes, Services and Standards (regulation). Places can be a key responsibility of an Outcomes Division, leading to the appointment of Place Managers to every area of the jurisdiction. Introduction “Place management” has been practiced in various parts of government in Australia1. Mostly, place managers have been appointed in ad hoc and essentially short term positions to deal with crisis situations – such as an area with a high crime rate. However, several organizations have undergone fundamental restructure with a view to making place management a central responsibility and putting place managers at the core of the organization, rather than the periphery. Place Management is a species of Outcome Management Inputs produce outputs, which lead to outcomes2. Organizations should strive to be efficient in the production of outputs and ensure that the resultant outcomes are effectively achieving the longer-term objectives sought by the organization and its stakeholders. Outcomes can be divided into either system or place outcomes. System outcomes are public policy outcomes that do not have a strong place focus – catchments, economic development, learning, healthiness, accessibility and the like. Published in The Journal of Place Management and Development Vol 1 No 1 March 2008 © John Mant 2008 [email protected] John Mant is an urban planner and retired lawyer, practicing in Sydney Australia. -

Refereed Proceedings

REFEREED PROCEEDINGS OF THE 40th ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND REGIONAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL RMIT UNIVERSITY MELBOURNE 5-7 DECEMBER 2016 EDITED BY PAUL DALZIEL AERU, LINCOLN UNIVERSITY LINCOLN, NEW ZEALAND Published in Canterbury New Zealand by: Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit P.O. Box 85084 Lincoln 7647 NEW ZEALAND Email: [email protected] Conference website: http://www.anzrsai.org ISBN: 978-0-473-38890-4 Copyright © ANZRSAI 2017 Individual chapters © the authors 2017 This publication is copyright. Other than for purposes of and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. ANZRSAI is pleased to acknowledge the conference sponsors. Lincoln University Page ii Preface The 40th Annual Conference of the Australian and New Zealand Regional Science Association International (ANZRSAI) was held at the RMIT University Melbourne from 5th to 7th December, 2016, co-hosted with the European Union Centre at RMIT and the RMIT Centre for People, Work and Organisation (with the RMIT Social Change Enabling Platform). A broad range of papers from academics, policy advisors and practitioners was presented to the conference. This publication contains the refereed proceedings of those contributed papers. Participants who submitted their full paper by the due date were eligible to be considered for these refereed proceedings. There were twelve papers submitted to a double blind refereeing process, all of which were accepted for this publication. -

Open Your Council

Open y o u r co unc il "...the future of every community lies in capturing the energ y, imagination, intelligence and passion of its people." – Ernesto Sirolli 1 Les Robinson newciti z e n B O O K S A c k n o w l e d g m e n ts Thanks to the following people who made critical (but wel- Contents come) comments on early drafts of this booklet: Lyn Cars o n , Jackie Ohlin, Simone Schwarz, Glen Holstock and Cynzia D e i - C o n t . This booklet is inspired by and draws on the work of many Making space for community . .4 people, especially: An unbalanced gove r n m e n t . .6 Lyn Carson (University of Sydney), whose lecture R a n d o m Selection: Achieving Representation in Planning d e a l s thoughtfully with the philosophy and practice of delibera- The corporate push . .8 tive democra c y. B reaking down barriers . .1 2 Roberta Ryan (University of NSW) and Mike Salvaris (Swinburne University of Technology), whose pioneering Community Indicators and Local Democracy project with six D e l i b e ra t i ve democracy . .1 6 A u s t ralian councils helped inspire this booklet. Neighbourhood democracy . .3 2 Associate Professor Kevin Sproats, Centre for Local Government Education and Research, University of Te c h n o l o g y, Sydney, whose paper Local Management or Measuring wellbeing . .4 6 Local Government neatly sets out many ideas about deliber- ative democra c y. -

1989 Vol.11 No2

Planning History Bulletin of the Planning History Group Vol. 11 No. 2 1989 Planning History BuUetin of the Planning History Group Contents lSSl 0267-0542 1 EDITORIAL Editor 2 Professor Denni Hardy NOTICES Sc.hool of Geography and Planning M1ddle ex Polytechnic Queensway ~~!!.~.~~~S _ ....... ~·--- ·~· .. ······~·-·····.... - .........................................................................-·········· ·············v··--«·«·"·--·····-................... - ................................ ~.. Enfield Middlesex Built Form versus Urb an Planning Legis lation of the Last Century: E 3 4SF Genius Loci versus International Influen ces . .. ... .. .. .. ...... ........ ....... .. · · . 4 Telephone 01-368 '1299 Extn 2299 H alina Dunin-Woyseth Telex 8954762 Urban Reconstr u ction in France after World War 11 .. .. .. .. .................... · .13 Fax 01-805 0702 Daniele Voldman Social Democratic Reform and Aus tralia's Cities: The Whitlam Legacy .............. .. 18 Associate Editor for the Americas Lio nel O rch a rd Or Marc A. Weiss 25 School of Architecture and Planning PORTS Massachusetts Institute o f Technology RE Building -l-209 Cambridge, 1A 02'139 Joint PHG/AESOP Planning His tory Pan el at Dortmund Congress .... ........ ...... 25 USA David Massey 26 Associate Editor for the Pacific SOURCES Or Robert Freestone DC Research John J ohnson Collection of Printed Ephemera, Bodleian Library, O xford ............. 26 Design Collaborative Pty. Ltd. Dennis Hard y 225 Clarence Street Sydney SW 2000 28 PLANNING HISTORY PRACTICE Australia .....:.... -

Evolution in Community Governance Building on What Works

[Cover page] EVOLUTION IN COMMUNITY GOVERNANCE BUILDING ON WHAT WORKS Volume 1: Report November 2011 0 EVOLUTION IN COMMUNITY GOVERNANCE: BUILDING ON WHAT WORKS Volume 1: Report November 2011 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by Peter McKinlay and Adrienne von Tunzelmann from McKinlay Douglas (Peter McKinlay is also Director of the Local Government Centre Auckland University of Technology), and Stefanie Pillora and Su Fei Tan from ACELG. The authors would like to acknowledge Daniel Grafton, Chris Watterson and Nancy Ly from ACELG who provided editorial and design assistance. ACELG would also like to acknowledge the representatives of the following councils and Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Ltd branches for their contribution to this research: The Councils Brewarrina Shire Council, NSW Central Coast Council, Tasmania City of Swan, Western Australia Golden Plains Shire, Victoria Mosman Municipal Council, NSW Playford City Council, South Australia Port Phillip City Council, Victoria Redland City Council, Queensland Surf Coast Shire, Victoria Tweed Shire, NSW Wiluna Shire, Western Australia Wyndham City Council, Victoria Yarra Ranges Council, Victoria The Community Banks Cummins District Community Bank, SA Gingin Community Bank, WA Logan Community bank, Qld Mt Barker Community Bank, WA Strathmore Community bank, Victoria Wentworth and District Community Bank, NSW Citing this report Please cite this report as: McKinlay P., Pillora, S., Tan, S.F., Von Tunzelmann, A. 2011. Evolution in Community Governance: Building on What Works. Australian -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION This is a list of works quoted frequently in the dictionary and of those which it might be difficult to find from the short reference given in citations. Pseudonymous works have usually been entered under the pseudonym, with the author’s actual name added within brackets. Cross references have been included if warranted. Definite and indefinite articles preceding tides of journals and newspapers have been omitted. Annual volumes of legislation, sessional publications of parliaments, and government gazettes have not been listed in the Bibliography. Where parliamentary publications are used as the source of citations, they have been referred to by abbreviations, the key to which will be found in the List of Abbreviations (p. XIV). Where legislation is the source of citations, references have been made in the following style: (Year of enactment) Acts (state or country) (Regnal year, where applicable) (Number) (Section) For example: 1896 Acts (N.S.W.) 59 Vic. no. 26 section 15. Page numbers for such references have not been included. Works held by the Australian War Memorial Library (many of which are ephemera and unlikely to be found elsewhere) are marked with an asterisk. Pauline Fanning BIBLOGRAPHY A A.I.M. frontier news Sydney 1930–34 (continued by Frontier news) ‘A.J.O.’ (A.J. Ogilvy) Sullivan and co.Hobart 1905 ‘A.L.F.’ (S. Terry) The history of Samuel Terry in Botany Bay London 1838 ‘A.M.’ (J. Murdoch) From Australia and Japan London 1892 A.N.F.C. review, 1953 Melbourne 1954 ABBIE, A.A. The original Australians Wellington, N.Z. 1969 ABBOTT, J.H.M.