Refereed Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and Professional Papers and Records Of

AIATSIS Library Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys 1937-1986 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY……………………………….…………...... page 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT…………………………..... page 3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION…………………………………………… page 4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW…………………………….……………..... page 5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………………………… page 6 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………... page 9 Awards Series 1 Awards, honours and related papers, 1949-1985 Journals, field notes and diaries Series 2 Journal, field notebooks, diaries and related papers, 1949-1980 Correspondence and related papers Series 3 General, 1937-1980 Series 4 Australian School of Pacific Administration, 1956-1961 Series 5 Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council (SSRC) project, 1963-1969 Series 6 Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, 1974-1984 Series 7 Aboriginal Land Fund Commission, 1974-1980 Series 8 Research School of Social Sciences (RSSS), Australian National University, correspondence and related papers, 1980-1981 Series 9 Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS), 1977-1985 Series 10 Aboriginal Treaty Committee (ATC), 1978-1984 MS 3775: C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys, 1937-1986 Series 11 Sundry, 1965-1981 Research project files Series 12 UNESCO Mission on Adult & Workers’ Education to S-E Asia, 1954-55 Series 13 Aborigines in -

Waterfall Way Corridor Strategy

B78 WATERFALLWAY DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY JULY 2017 WATERFALL WAY DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY July 2017 Waterfall Way DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY Draft for consultation I Draft only: actions subject to government priorities and funding availability B78 WATERFALL WAY DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY JULY 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE Heading east through Bellingen Main Street The Waterfall Way Corridor is during consultation will inform future planning, final actions will be subject to government located in Northern NSW and priorities and funding availability. extends from the Pacific Highway The Waterfall Way provides: at Raleigh to the NewDraft England for Highway at Armidale a distance of • The Waterfall Way is an important transport corridor, providing an east – west connection 170km. Traffic volumes along the between the Pacific and New England Waterfall Way vary in the rural highways. It connects rural communities to the sections from around 750 vehicles urban centres of Coffs Harbour and Armidale per day (vpd) betweenconsultation Dorrigo • It is a tourist route passing the waterfalls on the Dorrigo Mountain and provides access to the and Ebor to over 6,700vpd Dorrigo National Park between the Pacific Highway and • A transport route for the timber and Bellingen. agricultural industries. Key customers along the corridor include: This draft sets out the proposed strategic vision to manage and guide development of the Waterfall • Commuters; trips to urban centres, such as Way road corridor to improve safety, traffic Coffs Harbour, for employment and education efficiency and sustainability. There is no • Longer personal and work related educational, commitment to, or funding for, proposed actions health, recreational and business trips; identified in this draft. -

Undermining Mabo the Shaming of Manning Clark on Your Way, Sister

Vol. 3 No. 8 October 1993 $5.00 Undermining Mabo On your way, sister Frank Brennan Pamela Foulkes The shaming of Manning Clark Trading in union futures Rosamund Dalziel! PauiRodan In Memoriam D.J.O'H One thirty. This is the time I saw you last Braving death with a grin in the stilled ward. Invaded and insulted, you stood fast, Ready to fight, or ford The cold black stream that rings us all about Like Ocean. Some of it got into your eyes That afternoon, smarting you not to doubt But to a new surprise At what sheer living brings-as once Yeats Braced in a question bewilderment, love and dying. As the flesh declines, the soul interrogates, Failing and stili trying. On a field of green, bright water in their shade, Wattles, fused and diffused by a molten star, Are pledging spring to Melbourne. Grief, allayed A little, asks how you are. 'Green is life's golden tree', said Goethe, and I hope that once again you're in a green Country, gold-fired now, taking your stand, A seer amidst the seen. Peter Steele In Memory of Dinny O'Hearn I Outcome, upshot, lifelong input, All roads leading to a dark Rome, We stumble forward, foot after foot: II You have taken your bat and gone home. Though you had your life up to pussy's bow, He disappeared in the full brilliance of winter, The innings wound up far too quick yellow sun unfailing, the voice of Kennett But the nature of knowledge, you came to know, utterly itself away on Shaftesbury A venue, Is itself the flowering of rhetoric. -

Coffs Coast Regional

TO GLEN TO NYMBOIDA TO McPHERSONS TO GRAFTON INNES 28km ABCDE3km CROSSING 26km FTO GRAFTON 36km 41km G YURAYGIR HORTONS NAT PK CK NAT N WARRA 152º50'E Red Rock 152º10'E 153º10'E 151º50'E 152º00'E 153º00'E 152º20'E 152º30'E 152º40'E NAT PK (locality) RES o TOURIST DRIVE 19 rt Kookabookra h YARRAWARRA CHAELUNDI KA 30º00'S SHEAS NG ABORIGINAL 1 RED ROCK STATE FOREST 996 CHAELUNDI AR GUY FAWKES NOB SF 803 O CULTURAL CENTRE NATIONAL O HOLIDAY PARK Ben Lomond PARK RIVER k k e Towallum e e r e P Y r R Corindi Beach A C D IV C E Glenreagh SHERWOOD CORINDI BEACH R R W Fawkes BYRNES NAT RES H HOLIDAY PARK CLOUDS CREEK SCRUB Upper G LLANGOTHLIN I 10 O Corindi RD NAT RES H For detail see Map 8 N R LAKE The T Chaelundi Ck a E (locality) A MARENGO A Arrawarra Platypus are found in most RD l R W R Rest Area Junction l SF 318 a A Backwater K pools along the river 4WD beach access 12 LITTLE R w 1 O E KANGAROO Coast 1 u WEDDING LLANGOTHLIN O V B um I d BELLS Mullaway A s j NAT RES s R a K po RIVER CONGLOMERATE O h Woolgoolga Beach O Clouds Creek 12 O CHAELUNDI RD 4WD beach access K River an ST CONS Railway b NYMBOI - BINDERAY Railway Oban O SF 21 SF 349 For detail Woolgoolga AREA NATIONAL PARK GENTLE ANNIE see Map 3 s SF 111 d Little FOREST WAY n a Ma ELLIS SF 831 N uc l Riv re Misty Creek O B ca SOLITARY w er n T RD o g Lookout Vista Point F Cod Hole N o Woolgoolga ISLANDS Llangothlin MIST A Bucca Wards Mistake R A N Nana Glen Creek Picnic AKE Marengo Falls G y Hearnes Lake (locality) D m BAGAWA SF 30 13 Area NATIONAL I R Lower b WILD I S O V o Bucca Sandy Beach GARA D Ck i MT E For detail B d R CATTLE BUSHMANS R Sandy Beach A PARK HYLAND M a RD see Map 9 W CREEK Moleton SF NAT RES Y 11 Fiddamans Beach 318 N SF 488 LOWER M Billys Creek Platypus SF Emerald Beach 30º10'S A BUCCA le T 11 oy R Flat 536 Look at Me Now f 10 r DR e E S Headland b SF 29 E A N R A R 5 k G N Ck O MOONEE BEACH e O FO G R E F e 23 EST MOTHER OF DUCKS r Dundarrabin NATURE RESERVE P Norman Jolly R. -

N Coffs Harbour

To Inverell To Glen Innes, Brisbane To Grafton To Grafton To Brisbane Glenreagh Upper Arrawarra Warra Sheas Nob Corindi National Park State Forest 15 Guy Fawkes River RD Mullaway National Park Marengo Kangaroo River Tingha State Forest The Junction State Forest Locked Chaelundi Clouds gate Tingha Single Creek Woolgoolga Stone Woman Nymboi National Park Ben Lomond Llangothlin Binderay Lake National Sandy Beach River Park Backwater Ellis State Forest Bagawa Nana Misty Creek State Forest Glen Emerald Beach Guy 1 Little Llangothlin Guy Fawkes River Lookout Wandsworth Nature Reserve National Park GRAFTON Mount Wild Cattle Creek Moonee Beach HWY Wards Hyland State Forest Fawkes Platypus Flat Indwarra Mistake Nature Billys Creek Nature Reserve Reserve Lowanna Sapphire Beach Tenterden Llangothlin Mobong Picnic Area Coramba Dundurrabin Norman Jolly Tibbs Tree Tyringham Memorial Ulong TYRINGHAM RD Korora Hyland Cascade Karangi State Forest Cascade Nymboida National Park Dairyville The Basin Brooklana HWY Nature Reserve Aberfoyle RD Upper River ENGLAND Orara Dunvegan Coffs Harbour Bundarra Megan Bindarri Bostobrick National Park River North Junuy Juluum CORAMBA Guyra Aberfoyle Dorrigo National Park OLD EBOR Rampsbeck i Dorrigo Mother of Ducks GUYRA Hernani Locked gate Boambee Lagoon Dangar Falls National Park Toormina Nature Reserve Wongwibinda Guy Fawkes River Malpas 17 RD National Park Gangara Dorrigo Crossmaglen PACIFIC Dam i Never Never Sawtell 17 Lyndhurst Deer Picnic Area Baldersleigh Dorrigo Rainforest Centre Bonville Gwydir Black 78 Vale -

Annual Report 2004

2004 2005 ANNUAL REPORT MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS & SCIENCES INCORPORATING THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM & SYDNEY OBSERVATORY The Hon Bob Debus MP Attorney General, Minister for the Environment and Minister for the Arts Parliament House Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Minister On behalf of the Board of Trustees and in accordance with the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, we submit for presentation to Parliament the annual report of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences for the year ending 30 June 2005. Yours sincerely Dr Nicholas G Pappas Dr Anne Summers AO President Deputy President ISSN 0312-6013 © Trustees of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences 2005. Compiled by Mark Daly, MAAS. Design and production by designplat4m 02 9299 0429 Print run: 600. External costs: $14,320 Available at www.powerhousemuseum.com Contemporary photography by MAAS photography staff: Sotha Bourn, Geoff Friend, Marinco Kojdanovski, Jean-Francois Lanzarone and Sue Stafford (unless otherwise credited). Historical photos from Museum archives. Contents 02 President’s Foreword 03 Director’s Report 04 Mission and structure 05 Organisation chart 06 Progress against Strategic Plan 07 Goals 2005-06 08 Museum honours th 09 125 anniversary celebrations 10 Highlights of 2004-05 11 The Powerhouse Foundation 11 Evaluating our audiences, exhibitions and programs 12 Exhibition program 13 Travelling exhibitions 13 Public and education programs tm 15 SoundHouse and VectorLab 15 Sydney Observatory 16 Indigenous culture 16 Regional services 17 Migration -

City of Subiaco Attachments Development Services

CITY OF SUBIACO ATTACHMENTS DEVELOPMENT SERVICES COMMITTEE MEETING COUNCIL CHAMBERS 241 ROKEBY ROAD, SUBIACO TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 CONTENTS PAGE ITEM PAGE REPORT TITLE AND ATTACHMENT DESCRIPTION NO. NUMBER(S) D1 No. 136 (Lot 82) Gloster Street Subiaco – Extension to Term of 10 pages Development Approval for Single Storey Dwelling with Basement (7.2017.29) Attachment 1 – Development approval (8 March 2017) Attachment 2 – Location plan Attachment 3 – Site photographs D2 No. 2A (Lot 300) Cunningham Terrace, Daglish – Proposed Garage to 7 pages Single House – DA 7.2017.18 Attachment 1 – Plans for Determination Attachment 2 – Original development application plans (withdrawn) D3 No. 11 (Lot 35) Austin Street, Shenton Park – Two Storey Additions to 17 pages an Existing Two Storey Dwelling Attachment 1 – Development plans (8 February 2017) Attachment 2 – Development plans (22 May 2017) D4 Proposed Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area and Draft 25 pages Planning Policy 3.13 ‘Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area’ – adoption post advertising Attachment 1 – Map of proposed Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area Attachment 2 – Draft planning policy 3.13 ‘Daglish First Land Release Heritage Area’ – with tracked modifications Attachment 3 – Schedule of submissions including officer response D5 Proposed Daglish Workers’ Homes Board Heritage Area and Draft 6 pages Planning Policy 3.14 ‘Daglish Workers’ Homes Board Heritage Area’ – adoption post consultation Attachment 1 – Map of proposed Daglish Workers’ Homes Board Heritage Area Attachment -

Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 (Amendment No 1) Under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979

2011 No 578 New South Wales Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 (Amendment No 1) under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 I, the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure, make the following local environmental plan under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. TOM GELLIBRAND As delegate for the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure Published LW 11 November 2011 Page 1 2011 No 578 Clause 1 Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 (Amendment No 1) Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 (Amendment No 1) under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 1 Name of Plan This Plan is Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 (Amendment No 1). 2 Commencement This Plan commences on the day on which it is published on the NSW legislation website. 3 Land to which Plan applies This Plan applies to certain land to which Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 applies. 4Maps Each map adopted by Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 that is specified in Column 1 of the following Table is declared by this Plan to be amended or replaced, as the case requires, by the map specified opposite in Column 2 of the Table as approved by the Minister on the making of this Plan. Column 1 Column 2 Name of map being amended or Name of amending or replaced replacement map Bellingen Local Environmental Plan Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 Heritage Map 2010 Heritage Map (0600_COM_HER_003_080_20100 (0600_COM_HER_003_080_20110 622) 401) Bellingen Local Environmental Plan Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 Heritage -

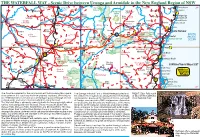

Waterfall Way

THE WATERFALL WAY - Scenic Drive between Urunga and Armidale in the New England Region of NSW º 30º Nymboida Ben Lomond Llangothlin Guy Fawkes Towallum Corinda Beach 33º 26 Lake Backwater 152 National Park Arrawarra Wandsworth 27 Mt Hyland Clouds 45 Glenreagh 13 Nature Creek Wards Res. 25 100 Mistake Billys Nana Glen Woolgoolga Tenterden Llangothlin Marengo Creek 117 11 Sandy Beach Bundarra Plain Georges Lowanna Emerald Beach HWY Dundurrabin 5 V Mountain 27 River Coramba Moonee Beach Tyr ingham Old Store Ulong Guyra Monkey Point V Cascade 15 Aberfoyle Gwydir 28 36 30 57 Korora 12 Wongwibinda 21 Megan Baldersleigh Black Hernani Bostobrick Brooklana 17 Abington Mountain Coffs Harbour 48 Dangar FallsDorrigo 34 Boambee 38 V Pine V Joey Knob Ebor 78 38 Dorrigo Nat Pk SOUTH Falls 13 Way 93 Rainforest Centre Bonville Mountain Cathedral Rock Sawtell PACIFIC Fernbrook 31 Valery 27 Mt Davidson National Park Ebor Sherrard Falls Thora Bongil Bongil Nat Park OCEAN Mitchells V V Terryburn Cathedral Rock Majors Point Repton Flat aterfall Point Darkwood Newell Raleigh 12 Yarrowyck W Falls Bellingen Mylestom 37 15 Lookout 11 River 32 Wollomombi River Kingstown Armidale Way Urunga Waterfall 80 Brierfield Bellinger Mt Gladstone V Newry 22 43 New England V Missabotti 28 25 Jeogla National Park Killiekrankie State Valla Beach 25 Rocky Forest Valla River 15 Hillgrove Wollomombi Mountain 24 Gorge Bowraville 120 Castle 45 14 Nambucca Heads 17 Doyle Oxley Wild Rivers Uralla Dangars 13 Watsons 43 Falls National Park Five Day 'The Pub WithTaylors Creek Creek Arm -

Anzac Memorial Annual Report 2016 17.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 –17 The Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building Anzac Memorial Annual Report 2016–2017 Hyde Park South, Sydney NSW 2000 Locked Bag 53 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 T 02 9267 7668 E [email protected] © 2017 The Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building. This report was first published in October 2017. View or download this report from the Anzac Memorial website: www.anzacmemorial.nsw.gov.au Cover: Photograph by Rob Tuckwell Photography This page: Anzac Memorial cross sections by Bruce Dellit, Architect, 1930. Courtesy NSW Government Architect’s Office 2 | ANZAC MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2016 –17 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE TRUSTEES 5 CONTACT INFORMATION 7 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 8 The building of the Memorial Description of the Memorial Rededication of the Memorial ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND RESPONSIBILITIES 12 Organisational chart Governance Guardians of the Anzac Memorial Staffing ANZAC MEMORIAL CENTENARY PROJECT 18 Project and construction highlights The Anzac Memorial Centenary Project exhibition design The Anzac Memorial Centenary Project art commission 2016–17 OPERATIONS 24 Visitor engagement and participation Exhibitions and displays Public programs, events and ceremonies Other commemorative activities Fundraising Building management and maintenance THE COLLECTION 30 Significant acquisitions Documentation Collection management Conservation Research Training Public enquiries Senior Historian and Curator WEBSITE AND SOCIAL MEDIA 36 CONSUMER REVIEWS 37 Services improved/changed in response to suggestions GENERAL DISCLOSURES -

Cyanobacteria)

573 Non-marine algae of Australia: 1. Survey of colonial gelatinous blue-green macroalgae (Cyanobacteria) Stephen Skinner and Timothy J. Entwisle Abstract Skinner, S. and Entwisle, T.J. (Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney, Mrs Macquaries Road, Sydney NSW 2000, Australia. e-mail: [email protected]) 2001. Non-marine algae of Australia: 1. Survey of colonial gelatinous blue-green macroalgae (Cyanobacteria). Telopea 9(3): 573–599. Non-planktonic freshwater and terrestrial blue-green algae (Cyanobacteria) large enough to be noticeable even to casual observers, are frequently encountered in Australia, but appear only occasionally in the literature. Sixteen species of gelatinous colonial blue-green algae (Cyanobacteria) from Australia, are documented here. Two species — Nostoc borzioides and Rivularia concentrica — are new to science, and nine (Aphanothece caldariorum Richter, A. pallida (Kützing) Rabenhorst; Nostochopsis lobatus H.C. Wood ex Bornet & Flahault; Rivularia aquatica de Wilde; Gloeotrichia pilgeri Schmidle; Dichothrix gypsophila (Kützing) Bornet & Flahault; Nostoc flagelliforme Berkley & Curtis; Nostoc pruniforme (L.) C. Agardh ex Bornet & Flahault; Nostoc gelatinosum Schousboe in Bornet) are newly recorded from Australia. The others are Rivularia beccariana; Cylindrospermum licheniforme; Cylindrospermum stagnale; Nostoc commune and Nostoc verrucosum. Keys to the genera and species occurring in Australia are provided. Introduction This is the first of an occasional series of papers documenting new algal records and new taxa from non-marine habitats in Australia. The information is floristic rather than monographic, responding to an urgent need for information about the diversity of algae in freshwater and terrestrial habitats in Australia. The descriptions and illustrations are from Australian material, while protologues or authoratitive oversees descriptions have been consulted. -

Dorrigo National Park Plan of Management

DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service October 1998 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 4 October 1998. Acknowledgements: This plan of management has been prepared by staff of the Dorrigo District Office of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Crown Copyright 1998. Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgement. ISBN 0 7310 7688 5 FOREWORD Dorrigo National Park has an area of 7 885 hectares and is located 4 kilometres east of Dorrigo township which in turn lies 590 kilometres by road from Sydney. Dorrigo township is the centre of the rich agricultural lands of the Dorrigo Plateau. The town of Bellingen lies 25 kilometres to the east of the park and is the main town servicing the Bellinger Valley. The mid-north coast is within one hours drive of the park with the increasing population of centres such as Coffs Harbour and Nambucca Heads an important factor in park use and management. Part of Dorrigo Mountain was first protected in 1901. The area of reserved lands was progressively enlarged and granted increased protection until in 1967 when it was reserved under the National Parks and Wildlife Act, 1967 as a State Park. Under the National Parks and Wildlife Act of 1974 Dorrigo State Park was accorded national park status. In 1986 it was incorporated in the World Heritage List as one of the Sub-tropical and Warm Temperate Rainforest Parks of Eastern Australia, now known as the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves of Australia. Dorrigo National Park is one of an important group of conservation areas on the Great Escarpment which include New England, Guy Fawkes River, Cathedral Rocks and Oxley Wild Rivers National Parks and Mount Hyland and Guy Fawkes River Nature Reserves.