Anomalous Dark Growth Rings in Black Cherry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHERRY Training Systems

PNW 667 CHERRY training systems L. Long, G. Lang, S. Musacchi, M. Whiting A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY n WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY n UNIVERSITY OF IDAHO in cooperation with MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY CHERRY training systems Contents Understanding the Natural Tree....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Training System Options.......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Rootstock Options.......................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Pruning and Training Techniques.....................................................................................................................................................5 Kym Green Bush............................................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Spanish Bush.....................................................................................................................................................................................................18 Steep Leader......................................................................................................................................................................................................25 -

Flowering and Fruiting of "Burlat" Sweet Cherry on Size-Controlling Rootstock

HORTSCIENCE 29(6):611–612. 1994. chart uses eight color chips to assess fruit color: 1 = light red to 8 = very dark, mahogany red. At the end of the growing season, all Flowering and Fruiting of ‘Burlat’ current-season’s shoot growth, >2.5 cm, was measured on each branch unit. Sweet Cherry on Size-controlling We analyzed the data as a factorial, ar- ranged in a completely randomized design, Rootstock with rootstock and age of branch portions as main effects. The least significant difference Frank Kappel was used for mean separation of main effects. Agriculture Canada, Research Station, Summerland, B.C. VOH IZO, Canada Results Jean Lichou The sample branches had similar BCSA, Ctifl, Centre de Balandran, BP 32, 30127 Bellegarde, France with the mean ranging from 3 to 3.7 cm2 for the Additional index words. Prunus avium, Prunus cerasus, Prunus mahaleb, fruit size, fruit branch units of the trees on the three root- stock. The mean for the branch units’ total numbers, dwarfing, Edabriz, Maxma 14, F12/1 shoot length ranged from 339 to 392 cm. Abstract. The effect of rootstock on the flowering and fruiting response of sweet cherries ‘Burlat’ branches on Edabriz had more (Prunus avium L.) was investigated using 4-year-old branch units. The cherry rootstock flowers than ‘Burlat’ branches on F1 2/1 or Edabriz (Prunus cerasus L.) affected the flowering and fruiting response of ‘Burlat’ sweet Maxma 14 when expressed as either total cherry compared to Maxma 14 and F12/1. Branches of trees on Edabriz had more flowers, number of flowers or number standardized by more flowers per spur, more spurs, more fruit, higher yields, smaller fruit, and a reduced shoot length (Table 1). -

FSC Public Search

CERTIFICATE Information from 2018/08/28 - 14:26 UTC Certificate Code CU-COC-816023 License Code FSC-C102167 MAIN ADDRESS Name Timber Link International Ltd. Address The Timber Office,Hazelwood Cottage,Maidstone Road,Hadlow Tonbridge TN11 0JH Kent UNITED KINGDOM Website http://www.timberlinkinternational.com CERTIFICATE DATA Status Valid First Issue Date 2010-10-16 Last Issue Date 2017-01-12 Expiry Date 2022-01-11 Standard FSC-STD-40-004 V3-0 GROUP MEMBER/SITES No group member/sites found. PRODUCTS Product Trade Species Primary Secondary Main Type Name Activity Activity Output Category W5 Solid Acer spp.; Alnus rubra var. pinnatisecta Starker; Alnus brokers/traders FSC wood serrulata; Apuleia leiocarpa; Betula spp.; Castanea sativa without physical Mix;FSC (sawn, P.Mill.; Cedrela odorata; Cedrus libani A. Rich.; Chlorocardium posession 100% chipped, rodiei (R.Schomb.) R.R.W.; Cylicodiscus gabunensis (Taub.) peeled) Harms; Dicorynia guianensis Amsh., D. paraensis Benth.; W5.2 Solid Dipterocarpus spp; Dipteryx odorata; Dryobalanops spp.; wood Dyera costulata (Miq.) Hook.f.; Entandrophragma cylindricum; boards Entandrophragma spp.; Entandrophragma utile; Eucalyptus spp; Fagus sylvatica L.; Fraxinus excelsior; Fraxinus americana; Gonystylus bancanus; Guibourtia spp.; Hymenaea courbaril; Intsia bijuga; Juglans nigra L.; Juglans regia L.; Khaya spp.; Larix sibirica; Liriodendron tulipifera L.; Lophira alata; Manilkara bidentata (A.DC.) A.Chev.; Microberlinia spp.; Milicia excelsa; Millettia laurentii; Nauclea diderrichii; Parashorea spp. (Urat mata, white seraya, gerutu); Peltogyne spp.*; Pinus rigida; Platanus occidentalis L; Prunus avium; Prunus serotina Ehrh.; Pseudotsuga menziesii; Pterocarpus soyauxii; Quercus alba; Quercus petraea; Quercus robur; Robinia pseudoacacia L.; Shorea balangeran; Shorea laevis Ridl.; Shorea spp.; Swietenia macrophylla; Tabebuia spp.; Tectona grandis; Terminalia ivorensis A. -

Occurrence and Distribution of Stem Pitting of Sweet Cherry Trees in Washington

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4. BOTHAST, R. J., and D. I. FENNELL. 1974. A purpose medium for fungi and bacteria. We wish to thank E. B. Lillehoj and his staff at the medium for rapid identification and enumeration Phytopathology 45:461-462. Northern Regional Research Center, SEA-USDA, of Aspergillus flavus and related organisms. 9. RAMBO, G. W., J. TUITE, and P. CRANE. Peoria, Mycologia IL, for aflatoxin analyses of these five 66:365-369. 1974. Preharvest inoculation and infection of 5. CHRISTENSEN, Aspergillus cultures. C. M., and H. H. KAUFMANN. dent corn ears with Aspergillus flavus and 1965. Deterioration of stored grains by fungi. Aspergillus parasiticus. Phytopathology Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 3:69-84. 64:797-800. 6. LILLEHOJ, LITERATURE CITED E. B., D. I. FENNELL, and W. F. 10. SHOTWELL, 0. L., M. L. GOULDEN, and C. KWOLEK. 1976. Aspergillus flavus and W. HESSELTINE. 1974. Aflatoxin: 1. ANDERSON, H. W., E. W. NEHRING, and W. Distribu- aflatoxin in Iowa corn before harvest. Science tion in contaminated R. WICHSER. 1975. Aflatoxin contamination corn. Cereal Chem. 193:495-496. 51:492-499. of corn in the field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 7. LILLEHOJ, E. B., W. F. KWOLEK, E. E. 11. TAUBENHAUS, 23:775-782. J. J. 1920. A study of the black VANDERGRAF, M. S. ZUBER, 0. H. and the yellow molds of ear 2. ANONYMOUS. 1972. Changes in official corn. Tex. Agric. CALVERT, N. WIDSTROM, M. C. FUTRELL, Exp. Stn. Bull. 270. method of analysis. Natural Poisons 26. B01-26. and A. J. BOCKHOLT. 1975. Aflatoxin 12. ZUBER, M. S., 0. B03. -

Prunus Mahaleb

Prunus mahaleb Prunus mahaleb in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats I. Popescu, G. Caudullo Prunus mahaleb L., commonly known as mahaleb cherry, forest edge it creates a scrub vegetation community together is a shrub or small tree with white flowers, producing dark with other shrubby species of the genera Rosa, Rubus, Prunus red edible plums. It is native to Central-South Europe and and Cornus, and other thermophile shrubs such as spindle tree North Africa, extending its range up to Central Asia. It is a (Euonymus europaeus), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), wild pioneer thermophilous plant, growing in open woodlands, privet (Ligustrum vulgare), etc.5, 19, 20. forest margins and riverbanks. Mahaleb cherry has been used for centuries for its fruits Frequency and its almond-tasting seeds inside the stone, especially in East < 25% Europe and the Middle East. More recently this plant has been 25% - 50% 50% - 75% used in horticulture as a frost-resistant rootstock for cherry > 75% Chorology plants. The mahaleb cherry, or St. Lucie’s cherry, (Prunus mahaleb Native L.) is a deciduous shrub or small tree, reaching 10 m tall. The 1-4 bark is dark brown, smooth and glossy . The young twigs are Ovate simple leaves with pointed tips and finely toothed margins. glandular with yellowish-grey hairs, becoming later brownish and (Copyright Andrey Zharkikh, www.flickr.com: CC-BY) hairless1, 3. The leaves are alternate, 4-7 cm long, broadly ovate, pointed, base rounded to almost cordate, margins finely saw- Threats and Diseases toothed, with marginal glands, glossy above and slightly hairy The mahaleb cherry is susceptible to fungi such as bracket along the midrib beneath. -

Tart Cherries in the Garden Sheriden Hansen, Tiffany Maughan, Brian Barlow, and Brent Black

September 2018 Horticulture/Fruit/2018-03pr Tart Cherries in the Garden Sheriden Hansen, Tiffany Maughan, Brian Barlow, and Brent Black Summary recommendations. A basic soil test will tell you the soil Tart cherry (Prunus cerasus), also known as sour cherry texture, pH, salinity, and will provide recommendations or pie cherry, is an excellent addition to home orchards. for soil nutrients. Amendments and some fertilizers A single tree can produce an abundant supply of cherries should be incorporated into the soil before planting. Tart for canning, drying, freezing, juicing, jams, preserves, cherries thrive in well-drained, loamy soil. Avoid heavy and baking. The trees are medium-sized, grow at a clay soils that remain wet as this can promote root rot moderate rate and can easily be tucked into a backyard and prevent trees from thriving. The ideal soil pH is 7.0, landscape. but tart cherries are adaptable and can be productive in alkaline soils with a pH below 8.0. Tart cherry is a member of the genus Prunus which is comprised of the stone fruits such as nectarine, peach, Rootstocks: Fruit trees are commonly grafted to and almond. Tart cherry is closely related to sweet rootstocks to control tree size and other characteristics. cherry (Prunus avium); however, tart cherry fruit is more The standard rootstock for tart cherry is ‘Mahaleb’. acidic, contains more juice, and is less firm than sweet Trees produced on ‘Mahaleb’ rootstocks are considered cherries. Tart cherry is native to an area in Hungary and full size trees and are typically 20 feet tall and wide. -

![Molecular Characterisation of Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) Genotypes Using Peach [Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch] SSR Sequences](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3865/molecular-characterisation-of-sweet-cherry-prunus-avium-l-genotypes-using-peach-prunus-persica-l-batsch-ssr-sequences-2943865.webp)

Molecular Characterisation of Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) Genotypes Using Peach [Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch] SSR Sequences

Heredity (2002) 89, 56–63 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy Molecular characterisation of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) genotypes using peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] SSR sequences AWu¨ nsch1 and JI Hormaza1,2 1Unidad de Fruticultura, Servicio de Investigacio´n Agroalimentaria, Campus de Aula Dei, Zaragoza, Spain A total of 76 sweet cherry genotypes were screened with 3.7 while the mean heterozygosity over the nine polymorphic 34 microsatellite primer pairs previously developed in peach. loci averaged 0.49. The results demonstrate the usefulness Amplification of SSR loci was obtained for 24 of the of cross-species transferability of microsatellite sequences microsatellite primer pairs, and 14 of them produced poly- allowing the discrimination of different genotypes of a fruit morphic amplification patterns. On the basis of polymor- tree species with sequences developed in other species of phism and quality of amplification, a set of nine primer pairs the same genus. UPGMA cluster analysis of the similarity and the resulting 27 informative alleles were used to identify data divided the ancient genotypes studied into two fairly 72 genotype profiles. Of these, 68 correspond to unique cul- well-defined groups that reflect their geographic origin, tivar genotypes, and the remaining four correspond to three one with genotypes originating in southern Europe and the cultivars that could not be differentiated from the two original other with the genotypes from northern Europe and North genotypes of which they are mutants, and two very closely America. related cultivars. The mean number of alleles per locus was Heredity (2002) 89, 56–63. -

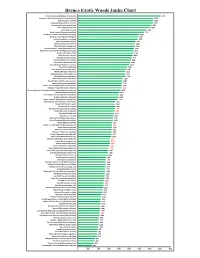

Janka Hardness Chart

Brenco Exotic Woods Janka Chart African Blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon) 4050 Kampanga / Snake Bean (Swartzia madagascariensis) 3690 Ipe (Tabebula serratifolia) 3680 Leadwood (Krugiodendron ferreum) 3660 Cumarurana (Taralea oppositifolia) 3590 Cumaru (Dipteryx odorata) 3540 Azobe (Lophira alata) 3350 Ebony Gaboon (Diospyros crassiflora) 3220 Rhodesian / Zambezi Teak (Baikiaea plurijuga) 2990 Pau Rosa / Dina (Swartzia fistuloides) 2940 Tali (Erythrophleum suaveolens) 2920 Jatoba (Hymenaea courbaril) 2820 Afina (Strombosia glaucescens) 2780 Okan (Cylicodiscus gabunensis) 2780 Pearwood African - Aboga (Mimusops lacera) 2730 Purpleheart South American (Peltogyne paniculata) 2710 Sucupira (Bowdichia nitida) 2700 Niove (Staudtia stipitata) 2680 Apomé (Cynometra ananta) 2630 Ataa (Pentaclethra macrophylla) 2580 Eveuss (Klainedoxa gabonensis) 2550 Missanda (Erythrophleum africanum) 2513 Difou (Morus mesozygia) 2400 Greenheart (Chlorocardium rodiei) 2350 Mufuka (Marquesia macroura) 2318 Mukulungu (Austanella congolensis) 2310 Mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) 2340 Muhuhu (Brachylaena hutchinsii) 2190 Essia (Combretodendron macrocarpum) 2180 Tigerwood (Astronium graveolens) 2160 Danta - Akumaba (Nesogordonia papaverifera) 2140 Sucupira - Tatabu (Diplotropis purpurea) 2140 African Rosewood / Copalwood Rhodesian (Guibourtia coleosperma) 2090 Chanfuta (Afzelia quanzensis) 2020 Vessambata / African Oak (Oldfieldia africana) 1990 Bubinga (Guibourtia demeusei) 1980 Danta - Kamema (Nesogordonia kabingaensis) 1940 Pecan (Carya illinoensis) Pecan Hickory -

Characterization of the USDA Tart Cherry (Prunus Cerasus) Collection in Geneva, NY Kyra Battaglia, Molly Carroll, Heidi Schwaninger, and Ben Gutierrez

Characterization of the USDA Tart Cherry (Prunus cerasus) Collection in Geneva, NY Kyra Battaglia, Molly Carroll, Heidi Schwaninger, and Ben Gutierrez USDA-ARS, Plant Genetics Resource Unit, Cornell AgriTech, Geneva,NY, 14456 Introduction Results The sweet cherry (Prunus avium) and that tart cherry (Prunus ● All anthocyanins, acids, and flavanols are correlated except for neochlorogenic acid cerasus) are the two main species grown commercially, with ● Boxplots show the distribution of the samples for variables tested, with the value for ‘Montmorency’ dominating the tart cherry production in the US1. ‘Montmorency’ highlighted in red Different characteristics are considered when determining the marketability of a cherry including fruit weight, flesh to pit ratio, acidity, TSS, aromatic compounds, and anthocyanin content.3,4 These characteristics also contribute to reported health benefits through the consumption of cherries, including a decrease in inflammation and a decrease in oxidative stress.2 With 200 cultivars worldwide1, understanding the diversity of each is important for both research and breeding purposes. This experiment analyzed the 130 tart cherry accessions across 7 Figure 5: PCA different species within the USDA’s collection, using data from Biplot. The first 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2019 in order to accurately assess the two components diversity. account for 54.9% of the variation. Figure 1: Gradient of select cherries from the USDA’s collection. From left to right, top to bottom: Montmorency, Mesabi, Ferracida, Emperor Francis, Spantsche Glaskirsche, Espera, Hudson, Englaise Timpurii, Ljubskaja x P. maximovici. Materials and Methods Sample Collection ●Determined which trees were not previously tested ●Collected 50 pieces of ripe fruit from trees that were only sampled once before, or that had not yet been tested Figure 6: Boxplots of all fruit quality characteristics. -

Genetic Relationships Among 10 Prunus Rootstock Species from China, Based on Simple Sequence Repeat Markers

J. AMER.SOC.HORT.SCI. 141(5):520–526. 2016. doi: 10.21273/JASHS03827-16 Genetic Relationships among 10 Prunus Rootstock Species from China, Based on Simple Sequence Repeat Markers Qijing Zhang and Dajun Gu1 Liaoning Institute of Pomology, Yingkou, Liaoning 115009, People’s Republic of China ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. microsatellite markers, banding patterns, phylogenetic analysis, subgenus classification, rootstock breeding ABSTRACT. To improve the efficiency of breeding programs for Prunus rootstock hybrids in China, we analyzed the subgenus status and relationship of 10 Chinese rootstock species, by using 24 sets of simple sequence repeat (SSR) primers. The SSR banding patterns and phylogenetic analysis indicated that subgenus Cerasus is more closely related to subgenus Prunophora than to subgenus Amygdalus, and that subgenus Lithocerasus is more closely related to subgenus Prunophora and subgenus Amygdalus than to subgenus Cerasus. In addition, Prunus triloba was more closely related to Prunus tomentosa than to the members of subgenus Amygdalus. Therefore, we suggest that P. tomentosa and P. triloba should be assigned to the same group, either to subgenus Lithocerasus or Prunophora, and we also propose potential parent combinations for future Prunus rootstock breeding. Prunus (Rosaceae) is a large genus with significant eco- peach, whereas Prunus salicina and Prunus sibirica can be nomic importance, since it includes a variety of popular stone used as a rootstock for cherry, plum, apricot, and peach. fruit species [e.g., peach (Prunus persica), apricot (Prunus Hybridization among Prunus species has been successful and armeniaca), almond (Prunus dulcis), and sweet cherry (Prunus has been taken up as an effective strategy for improving avium)]. -

Cherry Pollination Chart

POLLINIZERS Van (P. avium) Sam (P. avium) Bing (P. avium) Gold (P. avium) Lapins (P. avium) Kristin (P. avium) Skeena (P. avium) Rainier (P. avium) Vandalay (P. avium) Tehranive (P. avium) Blooming TimeBlooming** Sweetheart (P. avium) Sweet Ann (P. avium) North Star (P. cerasus) White Gold (P. avium) White Gold Royal Anne (P. avium) Evans Bali (P. cerasus) Montmorency (P. cerasus) Compact Stella (P. avium) Governor Wood (P. avium) English Morello (P. cerasus) Black Tartarian (Prunus avium) Bianco Rosato di Piemonte (P. cerasus) VARIETIES Carmine Jewel (P. cerasus x P. fruiticosa) Early Black Tartarian (Prunus avium) O Early Skeena (P. avium) O Early mid Gold (P. avium) + + + + + + + + + + + Early mid Kristin (P. avium) + + + + + + + + + + Early mid Lapins (P. avium) O Early mid Vandalay (P. avium) O Mid Bing (P. avium) + + + + + + + + + + + + + Mid Governor Wood (P. avium) O Mid Rainier (P. avium) + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + Mid Royal Anne (P. avium) + + + + Mid Sweetheart (P. avium) O Mid Tehranive (P. avium) O Mid Van (P. avium) + + + + + + + + + + + + + + Late Mid Compact Stella (P. avium) O Late Mid Sweet Ann (P. avium) + + + + + + + + + + + + + + Late Mid White Gold (P. avium) O Late Sam (P. avium) + + + + + + + + + + + + + Early Bianco Rosato di Piemonte (P. cerasus) O Late Mid Carmine Jewel (P. cerasus x P. fruiticosa) O Late Mid Evans Bali (P. cerasus) O Late Mid Montmorency (P. cerasus) O Late Mid North Star (P. cerasus) O Late English Morello (P. cerasus) O O = Self fertile/Universal Pollinator if blooming at same time + = Successful cross pollination Pie cherries will partially pollinate sweet cherries, but it isn't recommended because the sweet cherry production will be low. Cherry pollination can be complex Although Stella is considered a Universal Pollinator, it does not pollinate well with Bing - too genetically similar. -

Tree Factsheet Images at Pages 3, 4, 5

Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group Tree factsheet images at pages 3, 4, 5 Prunus avium L. taxonomy author, year Linnaeus 1753 synonym Cerasus avium family Rosaceae Eng. Name Wild Cherry, Sweet Cherry, Mazzard, Gean Dutch name Zoete Kers, Wilde Kers, Kriek, Boskers subspecies - varieties hybrids cultivars, frequently used: ‘Plena’ as a street tree and in parks ‘Landscape Bloom’ as a landscape tree many fruit varieties see Wikipedia references Schalk, P.H. 1989. Prunus avium de Boskers (in Dutch). in: Schmidt, P. 1989. Nederlandse boomsoorten II, Syllabus Vakgroep Bosbouw, Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen. http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kers http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cherry Plants for a Future Database; www.pfaf.org/index.html morphology crown habit tree, round to spreading max. height (m) 20-30 max. dbh (cm) 120 (180) actual size Great Britain + Ireland year …, d(...) 182, h 17, Studley Royal, Yorkshire, England year …, d(…) 75, h 28.5, Gurteen le Poer, Co. Waterford, Ireland actual size The Netherlands year 1900-1910, d(130) 117, h 18 year 1920-1930, d(130) 51, h 20 leaf length (cm) 6-15 leaf petiole (cm) 3-6 leaf colour upper surface green leaf colour under surface green leaves arrangement alternate flowering April flowering plant monoecious flower hermaphrodite flower diameter (cm) 2-3 flower male catkins length (cm) - pollination insects fruit; length cherry, drupe (=stone fruit); 1-2 cm fruit petiole (cm) 2-3 seed; length stone; 0,5 cm seed-wing length (cm) - weight 1000 seeds (g) 175 seeds ripen June-July seed dispersal birds (especially starling), fox, wood mouse habitat natural distribution Europe, Turkey, N.-Africa in N.W.