Handling Fate: the Ru Discourse on Ming 命

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Cultural Translation and Creative Misunderstanding in the Art Of

Cultural Translation and Creative Misunderstanding in the Art of Wenda Gu David Cateforis One of the major Chinese-born avant-garde artists of his generation, Wenda Gu (b. Shanghai, 1955) began his career as part of the ’85 Movement in China, relocated to the United States in 1987, and achieved international renown in the 1990s.1 Since the late 1990s Gu has spent increasing amounts of time back in China participating in that country’s booming contemporary art scene; he now largely divides his time between Brooklyn and Shanghai. This transnational experience has led Gu to create numerous art works dealing with East–West interchange. This paper introduces and briefly analyzes two of his recent projects, Forest of Stone Steles—Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry (1993–2005), and Cultural Transference—A Neon Calligraphy Series (2004–7), both of which explore creatively certain problems and paradoxes of attempts to translate between Chinese and English languages and cultures. A full understanding of these projects requires some knowledge of the work that first gained Gu international recognition, his united nations series of installations, begun in 1993.2 The series consists of a sequence of what Gu calls “monuments,” made principally of human hair fash- ioned into such elements as bricks, carpets, and curtains, and combined to create large quasi-architectural installations. Comprising national mon- uments made from hair collected within a single country and installed there, and transnational or “universal” monuments made of hair collected from around the world, Gu’s series uses blended human hair to suggest the utopian possibility of human unification through biological merger. -

Chinese Philosophy

CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Vatican Relations: Problems of Conflicting Authority, 1976–1986 EARLY HISTORY (Cambridge 1992). J. LEUNG, Wenhua Jidutu: Xianxiang yu lunz- heng (Cultural Christian: Phenomenon and Argument) (Hong Shang Dynasty (c.1600–c.1045 B.C.). Chinese Kong 1997). K. C. LIU, ed. American Missionaries in China: Papers philosophical thought took definite shape during the reign from Harvard Seminars (Cambridge 1966). Lutheran World Feder- of the Shang dynasty in Bronze Age China. During this ation/Pro Mundi Vita. Christianity and the New China (South Pasa- period, the primeval forms of ancestor veneration in Neo- dena 1976). L. T. LYALL, New Spring in China? (London 1979). J. G. LUTZ, ed. Christian Missions in China: Evangelist of What? lithic Chinese cultures had evolved to relatively sophisti- (Boston 1965). D. E. MACINNIS, Religion in China Today: Policy cated rituals that the Shang ruling house offered to their and Practice (Maryknoll, NY 1989). D. MACINNIS and X. A. ZHENG, ancestors and to Shangdi, the supreme deity who was a Religion under Socialism in China (Armonk, NY 1991). R. MAD- deified ancestor and progenitor of the Shang ruling fami- SEN, China Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil So- ciety (Berkeley 1998). R. MALEK and M. PLATE Chinas Katholiken ly. A class of shamans emerged, tasked with divination suchen neue (Freiburg 1987). Missiones Catholicae cura S. Con- and astrology using oracle bones for the benefit of the rul- gregationis de Propaganda Fide descriptae statistica (Rome 1901, ing class. Archaeological excavations have uncovered 1907, 1922, 1927). J. METZLER, ed. Sacrae Congregationis de Pro- elaborate bronze sacrificial vessels and other parapherna- paganda Fide Memoria Rerum, 1622–1972 (Rome 1976). -

Bol Shao Yung 20130225 Combined.Pdf (249.3Kb)

On Shao Yong’s Method for Observing Things The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bol, Peter. 2013. On Shao Yong’s Method for Observing Things. Monumenta Serica 61:287-299. Published Version http://www.monumenta-serica.de/monumenta-serica/publications/ journal/Catolog/Volume-LXI-2013.php Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17935880 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP On Shao Yong’s Method for Observing Things Peter K. Bol Charles H. Carswell Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University, 2 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Title: 論邵雍之觀物法 Abstract: Shao Yong’s “Inner Chapters on Observing Things” develops a method for understanding the unity of heaven and man, tracing the decline of civilization from antiquity, and determining how the present can return to the ideal socio-political order of antiquity. Shao’s method is based on dividing any topic into fours aspects (for example, four Classics, four seasons, four kinds of rulers, etc.) and generating the systematic relations between these four member sets. Although Shao’s method was unusual at the time, the questions he was addressing were shared with mid-eleventh statecraft thinkers. 摘要:邵雍在《觀物內篇》中發展出了一種獨特的方法,用來理解天人合一、追溯三代以 後之衰、並確定如何才能復原三代理想的社會政治秩序。邵雍的方法立足於將任意一個主 題劃分為四個種類(例如,四種經典,四種季節,四種統治者,等等),並賦予這四個種 類之間以系統性的聯繫。雖然邵雍的方法在當時並非尋常,可是他所試圖解決的問題卻是 其他十一世紀中葉的政治制度思想家所共同思考的。 Shao’s claim to philosophical importance is based on a single book, the Huangji jingshi shu 皇極 經世書 (Supreme Principles for Governing the World) and the various charts and diagrams associated with it, and to much lesser extent his collection of poems, the Jirang ji 擊壤集. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2019

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–743 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT C O N T E N T S Page I. -

Fuzzy Flexible Flow Shops on More Than Two Machine Centers

The Subtle Path to Heterodoxy: Reflections on the Concept of ‘Yiduan’ in the Jinsilu Milan Hejtmanek1 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Available Online October 2013 Neo-Confucian philosophy in - Key words: partook of a moral discourse that drew extensively on Song Chinese Heterodoxy; texts from the 11th and 12theth centuries. Korean Chosǒn Among period these, (1392 the Jinsilu1910) Korea; ; 1175 proved especially influential. This paper examines in detail a Neo-Confucianism; central(Reflections theme on of Things the Jinsilu: at Hand), heterodoxy compiled or by yiduan, Zhu Xi situatingand LüZuqian it both in Jinsilu.Chosǒn dynasty within the broader traditions of earlier Confucianism and as well as within the context of Neo-Confucian thought or daoxue as it was developed the 11th century, by the brothers Cheng Yi and Cheng Hao. It identifies three distinct, if overlapping conceptions of heterodoxy in the Jinsilu. The paper argues that the most pessimistic and aggressive attitude toward the danger of straying from the orthodox way and the condemning of those who had done so derived from Cheng Yi. His thought and sense of near dread concerning heterodoxy would prove highly influential in Chosǒn Korea. Introduction It is a remarkable feature of recorded human civilization that discourse drawn from a wide variety of times and places displays fierce struggles over what constitutes proper moral behavior and correspondingly what should be castigated as wrong and evil. Moral traditions in the West as diverse as Judaism, Islam, and in the East Buddhism, Hinduism, and Confucianism ha rhetorical strategies to argue both sides of complex ethical issues. The production and reproduction of dogma and its antithesis, heresy or heterodoxy, isve a bequeathed central activity prolific of any discourses system of deploying moral thought. -

Research on the Time When Ping Split Into Yin and Yang in Chinese Northern Dialect

Chinese Studies 2014. Vol.3, No.1, 19-23 Published Online February 2014 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/chnstd) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/chnstd.2014.31005 Research on the Time When Ping Split into Yin and Yang in Chinese Northern Dialect Ma Chuandong1*, Tan Lunhua2 1College of Fundamental Education, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, China 2Sichuan Science and Technology University for Employees, Chengdu, China Email: *[email protected] Received January 7th, 2014; revised February 8th, 2014; accepted February 18th, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Ma Chuandong, Tan Lunhua. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Ma Chuandong, Tan Lun- hua. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. The phonetic phenomenon “ping split into yin and yang” 平分阴阳 is one of the most important changes of Chinese tones in the early modern Chinese, which is reflected clearly in Zhongyuan Yinyun 中原音韵 by Zhou Deqing 周德清 (1277-1356) in the Yuan Dynasty. The authors of this paper think the phe- nomenon “ping split into yin and yang” should not have occurred so late as in the Yuan Dynasty, based on previous research results and modern Chinese dialects, making use of historical comparative method and rhyming books. The changes of tones have close relationship with the voiced and voiceless initials in Chinese, and the voiced initials have turned into voiceless in Song Dynasty, so it could not be in the Yuan Dynasty that ping split into yin and yang, but no later than the Song Dynasty. -

Methods of Observing Human Behavior SESP 372, Winter 2018 M/W 11:00-12:20 Annenberg Hall, Room G02

Methods of Observing Human Behavior SESP 372, Winter 2018 M/W 11:00-12:20 Annenberg Hall, Room G02 Professor: Kalonji Nzinga, Ph.D. [email protected] Office Hours: Monday & Wednesday 3:30-4:30 or by appointment Swift Hall, Room 219 Teaching Assistant: Christopher Leatherwood [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 2-3 or by appointment Course Description & Goals Many people trace the genre of ethnography back to the genesis of the academic field of anthropology in the mid 1800s. Edward Tylor is credited with “fathering” the approach that anthropologists take to studying remote cultures, publishing the first textbook on the subject Anthropology: an Introduction to the Study of Man and Civilization in 1881. The word ethnography basically describes a practice of exploring a new culture and writing some written account of it, combining the idea of ethno (culture) and graphy (writing). If we can settle on this definition; if we can agree that ethnography entails immersion in an unfamiliar culture and writing about it, then the genre traces back at the very least 1,000 years before Edward Tylor was born, to a Chinese writer by the name of Li Ao. Ao was born during the Tang Dynasty and travelled from Lo-yang to what would be modern day Guangzhou China (about 2500 miles of travel), keeping a detailed record of his travels. He was able to make this journey in the 9th Century on horseback. Ao’s Record of Coming to the South (來南) has been suggested to be the first example of a personal diary. -

On Leibniz and the I Ching

On Leibniz and the I Ching Sherwin Doroudi April 26, 2007 \I don't believe in I Ching." −John Winston Ono Lennon (1940-1980) Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), perhaps best known as the coinvenematics, philosophy, history, and numerous other fields, have led some to label him as a \universal genius." 1 His accomplishments are even more astounding when one considers that he achieved most of his mathematical and philosophical breakthroughs in his spare time, as he was legal counselor by profession. But one particularly curious fact about this man is that he was perhaps one of the first European sinophiles (lovers of Chinese culture). For whatever reason, however, his interest in all things Chinese, was barely touched upon by many of his biographers and even those who specifically documented his philosophical influences. 2 In fact many people are quite surprised to hear that Leibniz expressed interests in the orient, so it is only natural to ask why Leibniz was so interested in China. In particular, Leibniz was interested in the Chinese system of writing, which being an ideographic system, is quite different from the phonetic Roman alphabet used in the English, German, French, etc. Furthermore, Leibniz was particularly interested in a series of hexagrams found in the I Ching or Yi Jing (c. 1150 bce) which expressed numbers in what appeared to be binary form. 3 Leibniz, who was developing his own system of binary numbers at the time, was particularly fascinated that the Chinese supposedly had developed a concept of these numbers thousands of years earlier. This paper will investigate, albeit in breif, Leibniz' interests in the Chinese, and in particular the nature of this ancient binary system found in the I Ching hexagrams. -

Language Management in the People's Republic of China

LANGUAGE AND PUBLIC POLICY Language management in the People’s Republic of China Bernard Spolsky Bar-Ilan University Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, language management has been a central activity of the party and government, interrupted during the years of the Cultural Revolution. It has focused on the spread of Putonghua as a national language, the simplification of the script, and the auxiliary use of Pinyin. Associated has been a policy of modernization and ter - minological development. There have been studies of bilingualism and topolects (regional vari - eties like Cantonese and Hokkien) and some recognition and varied implementation of the needs of non -Han minority languages and dialects, including script development and modernization. As - serting the status of Chinese in a globalizing world, a major campaign of language diffusion has led to the establishment of Confucius Institutes all over the world. Within China, there have been significant efforts in foreign language education, at first stressing Russian but now covering a wide range of languages, though with a growing emphasis on English. Despite the size of the country, the complexity of its language situations, and the tension between competing goals, there has been progress with these language -management tasks. At the same time, nonlinguistic forces have shown even more substantial results. Computers are adding to the challenge of maintaining even the simplified character writing system. As even more striking evidence of the effect of poli - tics and demography on language policy, the enormous internal rural -to -urban rate of migration promises to have more influence on weakening regional and minority varieties than campaigns to spread Putonghua. -

Dai Zhen's Ethical Philosophy of the Human Being

Dai Zhen’s Ethical Philosophy of the Human Being By Ho Young Lee Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the Study of Religions School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2006 ProQuest Number: 10672979 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672979 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Abstract The moral philosophy of Dai Zhen can be summarised as “fulfil desires and express feelings”. Because he believed that life is the most cherished thing for all man and thing, he maintains that “whatever issues from desire is always for the sake of life and nurture.” He also claimed that “caring for oneself, and extending this care to those close to oneself, are both aspects of humanity" He set up a strong monastic moral philosophy based on individual human desire and feeling. As the title ‘Dai Zhen’s philosophy of the ethical human being’ demonstrate, human physical body and activities of life is ethical base of philosophy of Dai Zhen. -

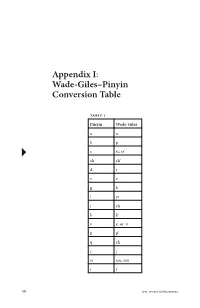

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25.